Scientists redesign bacteria to tackle the antibiotic resistance crisis

Probiotic bacteria can be engineered to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs by releasing chemicals that kill them.

In 1945, almost two decades after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, he warned that as antibiotics use grows, they may lose their efficiency. He was prescient—the first case of penicillin resistance was reported two years later. Back then, not many people paid attention to Fleming’s warning. After all, the “golden era” of the antibiotics age had just began. By the 1950s, three new antibiotics derived from soil bacteria — streptomycin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline — could cure infectious diseases like tuberculosis, cholera, meningitis and typhoid fever, among others.

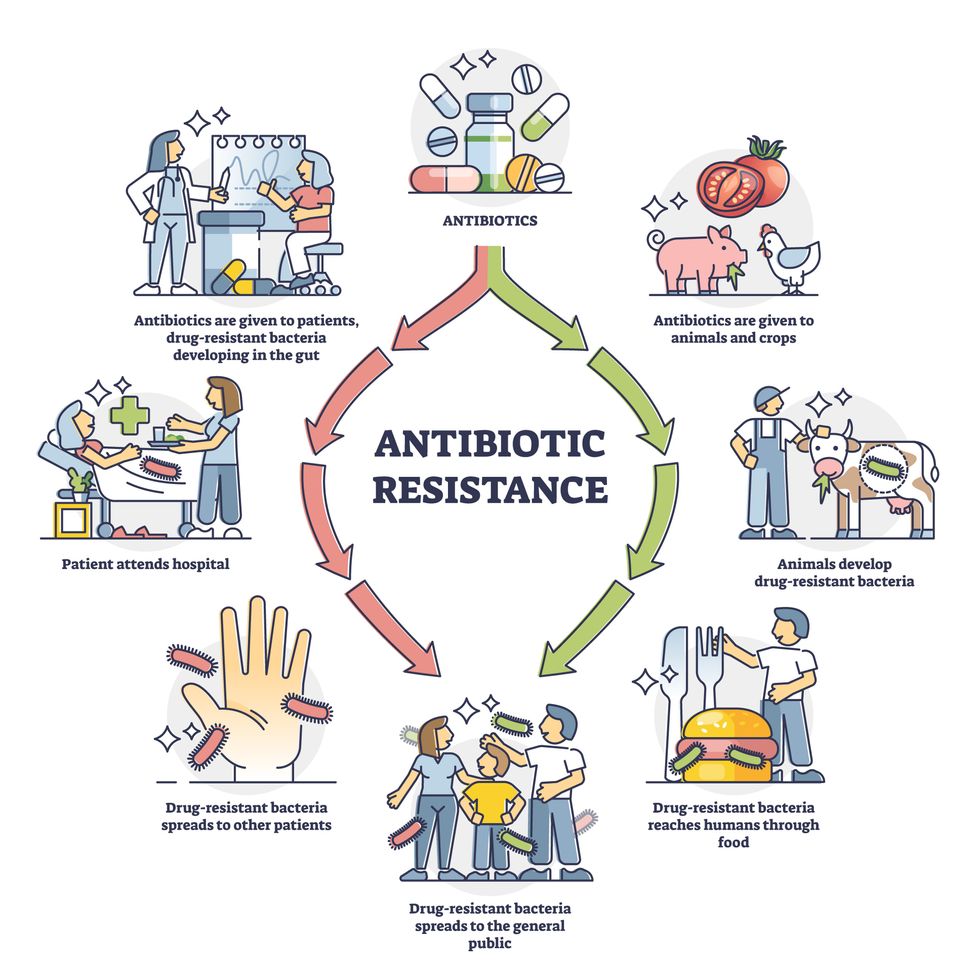

Today, these antibiotics and many of their successors developed through the 1980s are gradually losing their effectiveness. The extensive overuse and misuse of antibiotics led to the rise of drug resistance. The livestock sector buys around 80 percent of all antibiotics sold in the U.S. every year. Farmers feed cows and chickens low doses of antibiotics to prevent infections and fatten up the animals, which eventually causes resistant bacterial strains to evolve. If manure from cattle is used on fields, the soil and vegetables can get contaminated with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Another major factor is doctors overprescribing antibiotics to humans, particularly in low-income countries. Between 2000 to 2018, the global rates of human antibiotic consumption shot up by 46 percent.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring a promising avenue: the use of synthetic biology to engineer new bacteria that may work better than antibiotics. The need continues to grow, as a Lancet study linked antibiotic resistance to over 1.27 million deaths worldwide in 2019, surpassing HIV/AIDS and malaria. The western sub-Saharan Africa region had the highest death rate (27.3 people per 100,000).

Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

To make it worse, our remedy pipelines are drying up. Out of the 18 biggest pharmaceutical companies, 15 abandoned antibiotic development by 2013. According to the AMR Action Fund, venture capital has remained indifferent towards biotech start-ups developing new antibiotics. In 2019, at least two antibiotic start-ups filed for bankruptcy. As of December 2020, there were 43 new antibiotics in clinical development. But because they are based on previously known molecules, scientists say they are inadequate for treating multidrug-resistant bacteria. Researchers warn that if nothing changes, by 2050, antibiotic resistance could kill 10 million people annually.

The rise of synthetic biology

To circumvent this dire future, scientists have been working on alternative solutions using synthetic biology tools, meaning genetically modifying good bacteria to fight the bad ones.

From the time life evolved on earth around 3.8 billion years ago, bacteria have engaged in biological warfare. They constantly strategize new methods to combat each other by synthesizing toxic proteins that kill competition.

For example, Escherichia coli produces bacteriocins or toxins to kill other strains of E.coli that attempt to colonize the same habitat. Microbes like E.coli (which are not all pathogenic) are also naturally present in the human microbiome. The human microbiome harbors up to 100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells. The majority of them are beneficial organisms residing in the gut at different compositions.

The chemicals that these “good bacteria” produce do not pose any health risks to us, but can be toxic to other bacteria, particularly to human pathogens. For the last three decades, scientists have been manipulating bacteria’s biological warfare tactics to our collective advantage.

In the late 1990s, researchers drew inspiration from electrical and computing engineering principles that involve constructing digital circuits to control devices. In certain ways, every cell in living organisms works like a tiny computer. The cell receives messages in the form of biochemical molecules that cling on to its surface. Those messages get processed within the cells through a series of complex molecular interactions.

Synthetic biologists can harness these living cells’ information processing skills and use them to construct genetic circuits that perform specific instructions—for example, secrete a toxin that kills pathogenic bacteria. “Any synthetic genetic circuit is merely a piece of information that hangs around in the bacteria’s cytoplasm,” explains José Rubén Morones-Ramírez, a professor at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, Mexico. Then the ribosome, which synthesizes proteins in the cell, processes that new information, making the compounds scientists want bacteria to make. “The genetic circuit remains separated from the living cell’s DNA,” Morones-Ramírez explains. When the engineered bacteria replicates, the genetic circuit doesn’t become part of its genome.

Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut.

In 2000, Boston-based researchers constructed an E.coli with a genetic switch that toggled between turning genes on and off two. Later, they built some safety checks into their bacteria. “To prevent unintentional or deleterious consequences, in 2009, we built a safety switch in the engineered bacteria’s genetic circuit that gets triggered after it gets exposed to a pathogen," says James Collins, a professor of biological engineering at MIT and faculty member at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute. “After getting rid of the pathogen, the engineered bacteria is designed to switch off and leave the patient's body.”

Overuse and misuse of antibiotics causes resistant strains to evolve

Adobe Stock

Seek and destroy

As the field of synthetic biology developed, scientists began using engineered bacteria to tackle superbugs. They first focused on Vibrio cholerae, which in the 19th and 20th century caused cholera pandemics in India, China, the Middle East, Europe, and Americas. Like many other bacteria, V. cholerae communicate with each other via quorum sensing, a process in which the microorganisms release different signaling molecules, to convey messages to its brethren. Highly intelligent by bacterial standards, some multidrug resistant V. cholerae strains can also “collaborate” with other intestinal bacterial species to gain advantage and take hold of the gut. When untreated, cholera has a mortality rate of 25 to 50 percent and outbreaks frequently occur in developing countries, especially during floods and droughts.

Sometimes, however, V. cholerae makes mistakes. In 2008, researchers at Cornell University observed that when quorum sensing V. cholerae accidentally released high concentrations of a signaling molecule called CAI-1, it had a counterproductive effect—the pathogen couldn’t colonize the gut.

So the group, led by John March, professor of biological and environmental engineering, developed a novel strategy to combat V. cholerae. They genetically engineered E.coli to eavesdrop on V. cholerae communication networks and equipped it with the ability to release the CAI-1 molecules. That interfered with V. cholerae progress. Two years later, the Cornell team showed that V. cholerae-infected mice treated with engineered E.coli had a 92 percent survival rate.

These findings inspired researchers to sic the good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi onto the drug-resistant ones.

Three years later in 2011, Singapore-based scientists engineered E.coli to detect and destroy Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an often drug-resistant pathogen that causes pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis. Once the genetically engineered E.coli found its target through its quorum sensing molecules, it then released a peptide, that could eradicate 99 percent of P. aeruginosa cells in a test-tube experiment. The team outlined their work in a Molecular Systems Biology study.

“At the time, we knew that we were entering new, uncharted territory,” says lead author Matthew Chang, an associate professor and synthetic biologist at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the study. “To date, we are still in the process of trying to understand how long these microbes stay in our bodies and how they might continue to evolve.”

More teams followed the same path. In a 2013 study, MIT researchers also genetically engineered E.coli to detect P. aeruginosa via the pathogen’s quorum-sensing molecules. It then destroyed the pathogen by secreting a lab-made toxin.

Probiotics that fight

A year later in 2014, a Nature study found that the abundance of Ruminococcus obeum, a probiotic bacteria naturally occurring in the human microbiome, interrupts and reduces V.cholerae’s colonization— by detecting the pathogen’s quorum sensing molecules. The natural accumulation of R. obeum in Bangladeshi adults helped them recover from cholera despite living in an area with frequent outbreaks.

The findings from 2008 to 2014 inspired Collins and his team to delve into how good bacteria present in foods like yogurt and kimchi can attack drug-resistant bacteria. In 2018, Collins and his team developed the engineered probiotic strategy. They tweaked a bacteria commonly found in yogurt called Lactococcus lactis to treat cholera.

Engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut. --José Rubén Morones-Ramírez.

More scientists followed with more experiments. So far, researchers have engineered various probiotic organisms to fight pathogenic bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (leading cause of skin, tissue, bone, joint and blood infections) and Clostridium perfringens (which causes watery diarrhea) in test-tube and animal experiments. In 2020, Russian scientists engineered a probiotic called Pichia pastoris to produce an enzyme called lysostaphin that eradicated S. aureus in vitro. Another 2020 study from China used an engineered probiotic bacteria Lactobacilli casei as a vaccine to prevent C. perfringens infection in rabbits.

In a study last year, Ramírez’s group at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, engineered E. coli to detect quorum-sensing molecules from Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA, a notorious superbug. The E. coli then releases a bacteriocin that kills MRSA. “An antibiotic is just a molecule that is not intelligent,” says Ramírez. “On the other hand, engineered bacteria can be trained to target pathogens when they are at their most vulnerable metabolic stage in the human gut.”

Collins and Timothy Lu, an associate professor of biological engineering at MIT, found that engineered E. coli can help treat other conditions—such as phenylketonuria, a rare metabolic disorder, that causes the build-up of an amino acid phenylalanine. Their start-up Synlogic aims to commercialize the technology, and has completed a phase 2 clinical trial.

Circumventing the challenges

The bacteria-engineering technique is not without pitfalls. One major challenge is that beneficial gut bacteria produce their own quorum-sensing molecules that can be similar to those that pathogens secrete. If an engineered bacteria’s biosensor is not specific enough, it will be ineffective.

Another concern is whether engineered bacteria might mutate after entering the gut. “As with any technology, there are risks where bad actors could have the capability to engineer a microbe to act quite nastily,” says Collins of MIT. But Collins and Ramírez both insist that the chances of the engineered bacteria mutating on its own are virtually non-existent. “It is extremely unlikely for the engineered bacteria to mutate,” Ramírez says. “Coaxing a living cell to do anything on command is immensely challenging. Usually, the greater risk is that the engineered bacteria entirely lose its functionality.”

However, the biggest challenge is bringing the curative bacteria to consumers. Pharmaceutical companies aren’t interested in antibiotics or their alternatives because it’s less profitable than developing new medicines for non-infectious diseases. Unlike the more chronic conditions like diabetes or cancer that require long-term medications, infectious diseases are usually treated much quicker. Running clinical trials are expensive and antibiotic-alternatives aren’t lucrative enough.

“Unfortunately, new medications for antibiotic resistant infections have been pushed to the bottom of the field,” says Lu of MIT. “It's not because the technology does not work. This is more of a market issue. Because clinical trials cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the only solution is that governments will need to fund them.” Lu stresses that societies must lobby to change how the modern healthcare industry works. “The whole world needs better treatments for antibiotic resistance.”

Did researchers finally find a way to lick COVID?

A professor of medicine at the University of Michigan is researching whether lactoferrin, which is found in dairy products such as ice cream, can help to prevent COVID-19 infections.

Already vaccinated and want more protection from COVID-19? A protein found in ice cream could help, some research suggests, though there are a bunch of caveats.

The protein, called lactoferrin, is found in the milk of mammals and thus in dairy products, including ice cream. It has astounding antiviral properties that have been taken for granted and remain largely unexplored because it is a natural product, meaning that it cannot be patented and exploited by pharmaceutical companies.

Still, a few researchers in Europe and elsewhere have sought to better understand the compound.

Jonathan Sexton runs a drug screening program at the University of Michigan where cells are infected with a pathogen and then exposed to a library of the thousands of small molecule drug compounds – which can enter the body more easily than drugs with heavier molecules – approved by the FDA. In addition, the library includes compounds that passed phase 1 safety studies but later proved ineffective against the targeted disease. Each drug is dissolved in a solvent for exposure to the cells in the laborious testing process made feasible by robotic automation.

When COVID hit, researchers scrambled to identify any approved drug that might help fight the infection. Sexton decided to screen the drug library as well as some dietary supplements against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease. Sexton says that the grunt work fell to Jesse Wotring, “a very talented PhD student,” who pulled lactoferrin off the shelf. But the regular solvent used in the testing process would destroy the protein, so he had to take another approach and do all the work by hand.

“We were agnostic,” says Sexton, who didn't have a strong interest in lactoferrin or any of the other compounds in the library, but the data was quite clear; lactoferrin “consistently produced the best efficacy...it was the absolute home run.” The findings were published in separate papers last year and in February.

It turns out that lactoferrin has several different mechanisms of action against SARS-CoV-2, inhibiting the virus from entering cells, moving around within them and replicating. Lactoferrin also modulates the overall immune response, which makes it difficult for the virus to simultaneously mutate resistance to the protein at every step of replication. “It has broad efficacy against every [SARS-CoV-2] variant that we've tested,” he says.

From bench to bedside

Sexton's initial interest was to develop a drug for the acute phase of COVID infection, to treat a hospitalized patient or prevent that hospitalization. But with the quick approval of vaccines and drugs to treat the disease, he increasingly focused on ways to better prevent infection and inhibit spread of the virus.

“If you can get lactoferrin to persist in your upper GI tract, then it may very well prevent the primary infection, and that's what we're really interested in.” He reasoned that a chewing gum formula might release enough lactoferrin into the mucosal tissue of the mouth and upper airways to inhibit replication and give the immune system a chance to knock out the virus before it can establish a foothold. It could also reduce the amount of virus spread through talking.

To get enough lactoferrin to have a possible beneficial effect, one would have to drink gallons of milk a day, “and that would have other undesirable consequences, like getting extremely obese,” says Sexton. Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for severe COVID disease.

Testing that theory has been difficult. The easiest way would be a “challenge trial,” where volunteers take the drug, or in this case gum, are exposed to the pathogen, and protection is measured. Some COVID challenge studies have been conducted in Europe but the FDA remains hesitant to allow such a study in the U.S. A traditional prevention study would be like a vaccine trial, involving thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of volunteers over a period of months or years, and it would be very expensive. No one has stepped forward to foot the bill.

So the next step for Sexton is a clinical trial of newly diagnosed COVID patients who will be given standard of care treatment, and layered on top of that they will receive either lactoferrin, probably in pill form, or a placebo. He has identified initial funding. “We would study their viral load over time as well as their symptoms.”

One issue the FDA is grappling with in considering the proposed trial is that it typically decides whether to approve drugs from a factory by applying a rigorous standard, called good manufacturing practices, while food products, which are the source of lactoferrin, are produced under somewhat different standards. The agency still has not finalized rules on how to deal with natural products used as drugs, such as fecal transplants, convalescent plasma, or medical marijuana.

Sexton is frustrated by the delay because lactoferrin derived from bovine milk whey has been used for many decades as a protein supplement by athletes, it is a large component of most infant formula, and the largest number of clinical studies of lactoferrin involve premature infants. There is no question of its safety, he says.

Do it yourself

So what can you do while waiting for regulatory wheels to spin and clinical trial data to be generated?

Could a dose of Ben & Jerry's provide some protection against SARS-CoV-2?

Sexton chuckles at the suggestion. He supposes it couldn't hurt. But to get enough lactoferrin to have a possible beneficial effect, one would have to drink gallons of milk a day, “and that would have other undesirable consequences, like getting extremely obese.” Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for severe COVID disease.

Pseudo-milk products made from soy, almonds, oats, or other plant products do not contain lactoferrin; it has to come from a teat. So that rules them out.

Whey-based protein shakes might be a useful way to add lactoferrin to the diet.

Probably the best option is to take conventional gelatin capsules of lactoferrin that are widely available wherever supplements are sold. Sexton calculates that about a gram a day, four 250 milligram capsules, should do it. He advises two in the morning and two a night. “You really want to take them on an empty stomach...your stomach treats [the lactoferrin protein] like it would a steak” and chops it for absorption in the intestine, which you do not want. About 70 percent of lactoferrin can get through an empty stomach, but eating food cranks up digestive gastric acids and the amount of intact lactoferrin that gets through to the gut plummets.

Sexton cautions, “We have not determined clinical efficacy yet,” and he is not offering advice as a physician, but in the spirit of harm reduction, he realizes that some people are going to try things that might help them. Lactoferrin “is remarkably safe. And so people have to make their own decisions about what they are willing to take and what they are not,” he says.

In today's episode, Leaps.org interviews Camila dos Santos, a molecular biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, about her research on breasts and what makes them unique compared to any other part of the body.

My guest today for the Making Sense of Science podcast is Camila dos Santos, associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, who is a leading researcher of the inner lives of human mammary glands, more commonly known as breasts. These organs are unlike any other because throughout life they undergo numerous changes, first in puberty, then during pregnancies and lactation periods, and finally at the end of the cycle, when babies are weaned. A complex interplay of hormones governs these processes, in some cases increasing the risk of breast cancer and sometimes lowering it. Witnessing the molecular mechanics behind these processes in humans is not possible, so instead Dos Santos studies organoids—the clumps of breast cells donated by patients who undergo breast reduction surgeries or biopsies.

Show notes:

2:52 In response to hormones that arise during puberty, the breast cells grow and become more specialized, preparing the tissue for making milk.

7:53 How do breast cells know when to produce milk? It’s all governed by chemical messaging in the body. When the baby is born, the brain will release the hormone called oxytocin, which will make the breast cells contract and release the milk.

12:40 Breast resident immune cells are including T-cells and B-cells, but because they live inside the breast tissue their functions differ from the immune cells in other parts of the body,

17:00 With organoids—dimensional clumps of cells that are cultured in a dish—it is possible to visualize and study how these cells produce milk.

21:50 Women who are pregnant later in life are more likely to require medical intervention to breastfeed. Scientists are trying to understand the fundamental reasons why it happens.

26:10 Breast cancer has many risks factors. Generic mutations play a big role. All of us have the BRCA genes, but it is the alternation in the DNA sequence of the BRCA gene that can increase the predisposition to breast cancer. Aging and menopause are the risk factors for breast cancer, and so are pregnancies.

29:22 Women that are pregnant before the age of 20 to 25, have a decreased risk of breast cancer. And the hypothesis here is that during pregnancy breast cells more specialized, as specialized cells, they have a limited lifespan. It's more likely that they die before they turn into cancer.

33:08 Organoids are giving scientists an opportunity to practice personalized medicine. Scientists can test drugs on organoids taken from a patient to identify the most efficient treatment protocol.

Links:

Camila dos Santos’s Lab Page.

Editor's note: In addition to being a regular writer for Leaps.org, Lina Zeldovich is the guest host for today's episode of the Making Sense of Science podcast.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.