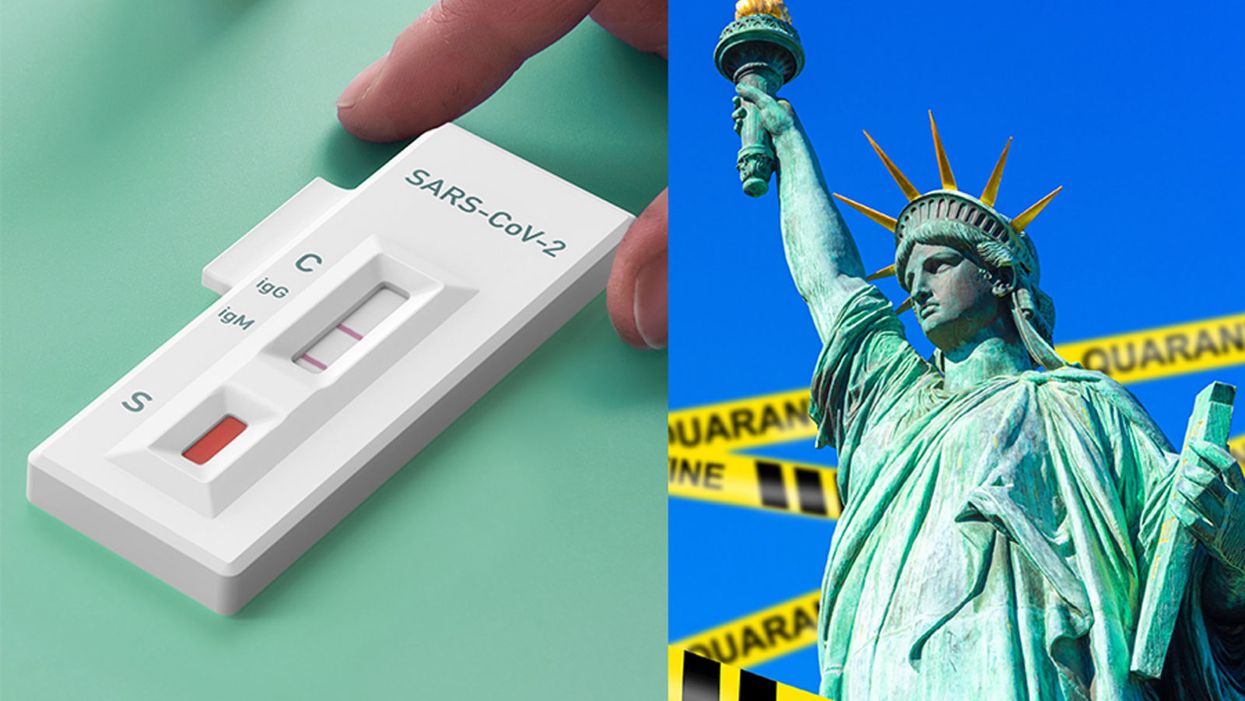

Antibody Testing Alone is Not the Key to Re-Opening Society

Immunity tests have too many unknowns right now to make them very useful in determining protective antibody status.

[Editor's Note: We asked experts from different specialties to weigh in on a timely Big Question: "How should immunity testing play a role in re-opening society?" Below, a virologist offers her perspective.]

With the advent of serology testing and increased emphasis on "re-opening" America, public health officials have begun considering whether or not people who have recovered from COVID-19 can safely re-enter the workplace.

"Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known."

Conventional wisdom holds that people who have developed antibodies in response to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, are likely to be immune to reinfection.

For most acute viral infections, this is generally true. However, SARS-CoV-2 is a new pathogen, and there are currently many unanswered questions about immunity. Can recovered patients be reinfected or transmit the virus? Does symptom severity determine how protective responses will be after recovery? How long will protection last? Understanding these basic features is essential to phased re-opening of the government and economy for people who have recovered from COVID-19.

One mechanism that has been considered is issuing "immunity certificates" to individuals with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. These certificates would verify that individuals have already recovered from COVID-19, and thus have antibodies in their blood that will protect them against reinfection, enabling them to safely return to work and participate in society. Although this sounds reasonable in theory, there are many practical reasons why this is not a wise policy decision to ease off restrictive stay-home orders and distancing practices.

Too Many Scientific Unknowns

Serology tests measure antibodies in the serum—the liquid component of blood, which is where the antibodies are located. In this case, serology tests measure antibodies that specifically bind to SARS-CoV-2 virus particles. Usually when a person is infected with a virus, they develop antibodies that can "recognize" that virus, so the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies indicates that a person has been previously exposed to the virus. Broad serology testing is critical to knowing how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, since testing capacity for the virus itself has been so low.

Tests for the virus measure amounts of SARS-CoV-2 RNA—the virus's genetic material—directly, and thus will not detect the virus once a person has recovered. Thus, the majority of people who were not severely ill and did not require hospitalization, or did not have direct contact with a confirmed case, will not test positive for the virus weeks after they have recovered and can only determine if they had COVID-19 by testing for antibodies.

In most cases, for most pathogens, antibodies are also neutralizing, meaning they bind to the virus and render it incapable of infecting cells, and this protects against future infections. Immunity certificates are based on the assumption that people with antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2 will be protected against reinfection. The problem is that we've only known that SARS-CoV-2 existed for a little over four months. Although studies so far indicate that most (but not all) patients with confirmed COVID-19 cases develop antibodies, we don't know the extent to which antibodies are protective against reinfection, or how long that protection will last. Immunity certificates cannot certify what is not known.

The limited data so far is encouraging with regard to protective immunity. Most of the patient sera tested for antibodies show reasonable titers of IgG, the type of antibodies most likely to be neutralizing. Furthermore, studies have shown that these IgG antibodies are capable of neutralizing surrogate viruses as well as infectious SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory tests. In addition, rhesus monkeys that were experimentally infected with SARS-CoV-2 and allowed to recover were protected from reinfection after a subsequent experimental challenge. These data tentatively suggest that most people are likely to develop neutralizing IgG, and protective immunity, after being infected by SARS-CoV-2.

However, not all COVID-19 patients do produce high levels of antibodies specific for SARS-CoV-2. A small number of patients in one study had no detectable neutralizing IgG. There have also been reports of patients in South Korea testing PCR positive after a prior negative test, indicating reinfection or reactivation. These cases may be explained by the sensitivity of the PCR test, and no data have been produced to indicate that these cases are genuine reinfection or recurrence of viral infection.

Complicating matters further, not all serology tests measure antibody titers. Some rapid serology tests are designed to be binary—the test can either detect antibodies or not, but does not give information about the amount of antibodies circulating. Based on our current knowledge, we cannot be certain that merely having any level of detectable antibodies alone guarantees protection from reinfection, or from a subclinical reinfection that might not cause a second case of COVID-19, but could still result in transmission to others. These unknowns remain problematic even with tests that accurately detect the presence of antibodies—which is not a given today, as many of the newly available tests are reportedly unreliable.

A Logistical and Ethical Quagmire

While most people are eager to cast off the isolation of physical distancing and resume their normal lives, mere desire to return to normality is not an indicator of whether those antibodies actually work, and no certificate can confer immune protection. Furthermore, immunity certificates could lead to some complicated logistical and ethical issues. If antibodies do not guarantee protective immunity, certifying that they do could give antibody-positive people a false sense of security, causing them to relax infection control practices such as distancing and hand hygiene.

"We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper."

Certificates could be forged, putting susceptible people at higher exposure risk. It's not clear who would issue them, what they would entitle the bearer to do or not do, or how certification would be verified or enforced. There are many ways in which such certificates could be used as a pretext to discriminate against people based on health status, in addition to disability, race, and socioeconomic status. Tracking people based on immune status raises further concerns about privacy and civil rights.

Rather than issuing documents confirming immune status, we should instead "re-open" society cautiously, with widespread virus and serology testing to accurately identify and isolate infected cases rapidly, with immediate contact tracing to safely quarantine and monitor those at exposure risk. Broad serosurveillance must be coupled with functional assays for neutralization activity to begin assessing how protective antibodies might actually be against SARS-CoV-2 infection. To understand how long immunity lasts, we should study antibodies, as well as the functional capabilities of other components of the larger immune system, such as T cells, in recovered COVID-19 patients over time.

We should not, however, place our faith in assumptions and make return to normality contingent on an arbitrary and uninformative piece of paper. Re-opening society, the government, and the economy depends not only on accurately determining how many people have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, but on a deeper understanding of how those antibodies work to provide protection.

Podcast: Trusting Science with Dr. Sudip Parikh, CEO of AAAS

The "Making Sense of Science" podcast features interviews with leading experts about health innovations and the big ethical and social questions they raise. The podcast is hosted by Matt Fuchs, editor of the award-winning science outlet Leaps.org.

As Pew research showed last month, many Americans have less confidence in science these days - our collective trust has declined to levels below when the pandemic began. But leaders like Dr. Sudip Parikh are taking important steps to more fully engage people in scientific progress, including breakthroughs that could benefit health and prevent disease. In January 2020, Sudip became the 19th Chief Executive Officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), an international nonprofit that seeks to advance science, engineering and innovation throughout the world, with 120,000 members in 91 countries. He is the executive publisher of Science, one of the top academic journals in the world, and the Science family of journals.

Listen to the episode

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

In this episode, Sudip and I talk about:

- Reasons to be excited about health innovations that could come to fruition in the next several years.

- Sudip's thoughts about areas of health innovation where we should be especially cautious.

- Strategies for scientists and journalists to instill greater trust in science.

- How to tap into and nurture kids' passion for STEM subjects.

- The best roles for experts to play in society and the challenges they face.

And we pack several other fascinating topics into our 35 minutes. Here are links to check out and learn more about Sudip Parikh and AAAS:

- Sudip Parikh's official bio - https://www.aaas.org/person/sudip-parikh

- Sudip Parikh, Why We Must Rebuild Trust in Science, Trend Magazine, Feb. 9, 2021 - https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trend/archive/winter-...

- Follow Sudip on Twitter - https://twitter.com/sudipsparikh

- AAAS website - https://www.aaas.org/

- AAAS podcast - https://www.science.org/podcasts

- The latest issue of Science - https://www.science.org/

- Science Journals homepage - https://www.science.org/journals

- AAAS Mentor Resources - https://www.aaas.org/stemmentoring

- AAAS Science Journalism Awards - https://sjawards.aaas.org/enter

- Pew Research Center Report, Americans' Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines, Feb. 15, 2022 https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/ame...

An implant, combined with the glasses and tiny video camera modeled in this photo, could improve the eyesight of millions of people with degenerative eye diseases in the coming years.

For millions of people with macular degeneration, treatment options are slim. The disease causes loss of central vision, which allows us to see straight ahead, and is highly dependent on age, with people over 75 at approximately 30% risk of developing the disorder. The BrightFocus Foundation estimates 11 million people in the U.S. currently have one of three forms of the disease.

Recently, ophthalmologists including Daniel Palanker at Stanford University published research showing advances in the PRIMA retinal implant, which could help people with advanced, age-related macular degeneration regain some of their sight. In a feasibility study, five patients had a pixelated chip implanted behind the retina, and three were able to see using their remaining peripheral vision and—thanks to the implant—their partially restored central vision at the same time.

Should people with macular degeneration be excited about these results?

“Every week, if not every day, patients come to me with this question because it's devastating when they lose their central vision,” says retinal surgeon Lynn Huang. About 40% of her patients have macular degeneration. Huang tells them that these implants, along with new medications and stem cell therapies, could be useful in the coming years.

“The goal here is to replace the missing photoreceptors with photovoltaic pixels, basically like little solar panels,” Palanker says.

That implant, a pixelated chip, works together with a tiny video camera on a specially designed pair of eyeglasses, which can be adjusted for each patient’s prescription. The video camera relays processed images to the chip, which electrically stimulates inner retinal neurons. These neurons, in turn, relay information to the brain’s visual cortex through the optic nerve. The chip restores patients’ central sight, but not completely. The artificial vision is basically monochromatic (whitish-yellowish) and fairly blurry; patients were still legally blind even after the implant, except when using a zoom function on the camera, but those with proper chip placement could make out large letters.

“The goal here is to replace the missing photoreceptors with photovoltaic pixels, basically like little solar panels,” Palanker says. These pixels, located on the implanted chip, convert light into pulsed electrical currents that stimulate retinal neurons. In time, Palanker hopes to improve the chips, resulting in bigger boosts to visual acuity.

The pixelated chips are surgically implanted during a process Palanker admits is still “a surgical learning curve.” In the study, three chips were implanted correctly, one was placed incorrectly, and another patient’s chip moved after the procedure; he did not follow post-surgical recommendations. One patient passed away during the study for unrelated reasons.

University of Maryland retinal specialist Kenneth Taubenslag, who was not involved in the study, said that subretinal surgeries have become less common in recent years, but expects implants to spur improvements in these techniques. “I think as people get more experience, [they’ll] probably get more reliable placement of the implant,” he said, pointing out that even the patient with the misplaced chip was able to gain some light perception, if not the same visual acuity as other patients.

Retinal implants have come under scrutiny lately. IEEE Spectrum reported that Second Sight, manufacturer of the Argus II implant used for people with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disease that causes vision loss, would no longer support the product. After selling hundreds of the implants at $150,000 apiece, company leaders announced they’d “decided to pursue an orderly wind down” of Second Sight in March 2020 in the wake of financial issues. Last month, the company announced a merger, shifting its focus to a new retinal implant, raising questions for patients who have Argus II implants.

Retinal surgeon Eugene de Juan of the University of California, San Francisco, was involved with early studies of the Argus implants, though his participation ended over a decade ago, before the device was marketed by Second Sight. He says he would consider recommending future implants to patients with macular degeneration, given the promise of the technology and the lack of other alternatives.

“I tell my patients that this is an area of active research and development, and it's getting better and better, so let's not give up hope,” de Juan says. He believes cautious optimism for Palanker’s implant is appropriate: “It's not the first, it's not the only, but it's a good approach with a good team.”