Medical Breakthroughs Set to be Fast-Tracked by Innovative New Health Agency

Pippy Rogers, second from left, with her four siblings, who worry that they are at risk for Alzheimer's and are calling for an acceleration of research.

In 2007, Matthew Might's son, Bertrand, was born with a life-threatening disease that was so rare, doctors couldn't diagnose it. Might, a computer scientist and biologist, eventually realized, "Oh my gosh, he's the only patient in the world with this disease right now." To find effective treatments, new methodologies would need to be developed. But there was no process or playbook for doing that.

Might took it upon himself, along with a team of specialists, to try to find a cure. "What Bertrand really taught me was the visceral sense of urgency when there's suffering, and how to act on that," he said.

He calls it "the agency of urgency"—and patients with more common diseases, such as cancer and Alzheimer's, often feel that same need to take matters into their own hands, as they find their hopes for new treatments running up against bureaucratic systems designed to advance in small, steady steps, not leaps and bounds. "We all hope for a cure," said Florence "Pippy" Rogers, a 65-year-old volunteer with Georgia's chapter of the Alzheimer's Association. She lost her mother to the disease and, these days, worries about herself and her four siblings. "We need to keep accelerating research."

We have a fresh example of what can be achieved by fast-tracking discoveries in healthcare: Covid-19 vaccines.

President Biden has pushed for cancer moonshots since the disease took the life of his son, Beau, in 2015. His administration has now requested $6.5 billion to start a new agency in 2022, called the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or ARPA-H, within the National Institutes of Health. It's based on DARPA, the Department of Defense agency known for hatching world-changing technologies such as drones, GPS and ARPANET, which became the internet.

We have a fresh example of what can be achieved by fast-tracking discoveries in healthcare: Covid-19 vaccines. "Operation Warp Speed was using ARPA-like principles," said Might. "It showed that in a moment of crisis, institutions like NIH can think in an ARPA-like way. So now the question is, why don't we do that all the time?"

But applying the DARPA model to health involves several challenging decisions. I asked experts what could be the hardest question facing advocates of ARPA-H: which health problems it should seek to address. "All the wonderful choices lead to the problem of which ones to choose and prioritize," said Sudip Parikh, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and executive publisher of the Science family of journals. "There is no objectively right answer."

The Agency of Urgency

ARPA-H will borrow at least three critical ingredients from DARPA: goal-oriented project managers, many from industry; aggressive public-private partnerships; and collaboration among fields that don't always interact. The DARPA concept has been applied to other purposes, including energy and homeland security, with promising results. "We're learning that 'ARPA-ism' is a franchisable model," said Might, a former principal investigator on DARPA projects.

The federal government already pours billions of dollars into advancing research on life-threatening diseases, with much of it channeled through the National Institutes of Health. But the purpose of ARPA-H "isn't just the usual suspects that NIH would fund," said David Walt, a Harvard biochemist, an innovator in gene sequencing and former chair of DARPA's Defense Science Research Council. Whereas some NIH-funded studies aim to gradually improve our understanding of diseases, ARPA-H projects will give full focus to real-world applications; they'll use essential findings from NIH research as starting points, drawing from them to rapidly engineer new technologies that could save lives.

And, ultimately, billions in healthcare costs, if ARPA-H lives up to its predecessor's track record; DARPA's breakthroughs have been economic game-changers, while its fail-fast approach—quickly pulling the plug on projects that aren't panning out—helps to avoid sunken costs. ARPA-H could fuel activities similar to the human genome project, which used existing research to map the base pairs that make up DNA, opening new doors for the biotech industry, sparking economic growth and creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

Despite a nearly $4 trillion health economy, "we aren't innovating when it comes to technological capabilities for health," said Liz Feld, president of the Suzanne Wright Foundation for pancreatic cancer.

Individual Diseases Ripe for Innovation

Although the need for innovation is clear, which diseases ARPA-H should tackle is less apparent. One important consideration when choosing health priorities could be "how many people suffer from a disease," said Nancy Kass, a professor of bioethics and public health at Johns Hopkins.

That perspective could justify cancer as a top objective. Cancer and heart disease have long been the two major killers in the U.S. Leonidas Platanias, professor of oncology at Northwestern and director of its cancer center, noted that we've already made significant progress on heart disease. "Anti-cholesterol drugs really have a wide impact," he said. "I don't want to compare one disease to another, but I think cancer may be the most challenging. We need even bigger breakthroughs." He wondered whether ARPA-H should be linked to the part of NIH dedicated to cancer, the National Cancer Institute, "to take maximum advantage of what happens" there.

Previous cancer moonshots have laid a foundation for success. And this sort of disease-by-disease approach makes sense in a way. "We know that concentrating on some diseases has led to treatments," said Parikh. "Think of spinal muscular atrophy or cystic fibrosis. Now, imagine if immune therapies were discovered ten years earlier."

But many advocates think ARPA-H should choose projects that don't revolve around any one disease. "It absolutely has to be disease agnostic," said Feld, president of the pancreatic cancer foundation. "We cannot reach ARPA-H's potential if it's subject to the advocacy of individual patient groups who think their disease is worse than the guy's disease next to them. That's not the way the DARPA model works." Platanias agreed that ARPA-H should "pick the highest concepts and developments that have the best chance" of success.

Finding Connections Between Diseases

Kass, the Hopkins bioethicist, believes that ARPA-H should walk a balance, with some projects focusing on specific diseases and others aspiring to solutions with broader applications, spanning multiple diseases. Being impartial, some have noted, might involve looking at the total "life years" saved by a health innovation; the more diseases addressed by a given breakthrough, the more years of healthy living it may confer. The social and economic value should increase as well.

For multiple payoffs, ARPA-H could concentrate on rare diseases, which can yield important insights for many other diseases, said Might. Every case of cancer and Alzheimer's is, in a way, its own rare disease. Cancer is a genetic disease, like his son Bertrand's rare disorder, and mutations vary widely across cancer patients. "It's safe to say that no two people have ever actually had the same cancer," said Might. In theory, solutions for rare diseases could help us understand how to individualize treatments for more common diseases.

Many experts I talked with support another priority for ARPA-H with implications for multiple diseases: therapies that slow down the aging process. "Aging is the greatest risk factor for every major disease that NIH is studying," said Matt Kaeberlein, a bio-gerontologist at the University of Washington. Yet, "half of one percent of the NIH budget goes to researching the biology of aging. An ARPA-H sized budget would push the field forward at a pace that's hard to imagine."

Might agreed. "It could take ARPA-H to get past the weird stigmas around aging-related research. It could have a tremendous impact on the field."

For example, ARPA-H could try to use mRNA technology to express proteins that affect biological aging, said Kaeberlein. It's an engineering project well-suited to the DARPA model. So is harnessing machine learning to identify biomarkers that assess how fast people are aging. Biological aging clocks, if validated, could quickly reveal whether proposed therapies for aging are working or not. "I think there's huge value in that," said Kaeberlein.

By delivering breakthroughs in computation, ARPA-H could improve diagnostics for many different diseases. That could include improving biowearables for continuously monitoring blood pressure—a hypothetical mentioned in the White House's concept paper on ARPA-H—and advanced imaging technologies. "The high cost of medical imaging is a leading reason why our healthcare costs are the highest in the world," said Feld. "There's no detection test for ALS. No brain detection for Alzheimer's. Innovations in detection technology would save on cost and human suffering."

Some biotech companies may be skeptical about the financial rewards of accelerating such technologies. But ARPA-H could fund public-private partnerships to "de-risk" biotech's involvement—an incentive that harkens back to the advance purchase contracts that companies got during Covid. (Some groups have suggested that ARPA-H could provide advance purchase agreements.)

Parikh is less bullish on creating diagnostics through ARPA-H. Like DARPA, Biden's health agency will enjoy some independence from federal oversight; it may even be located hundreds of miles from DC. That freedom affords some breathing room for innovation, but it could also make it tougher to ensure that algorithms fully consider diverse populations. "That part I really would like the government more involved in," Parikh said.

Might thinks ARPA-H should also explore innovations in clinical trials, which many patients and medical communities view as grindingly slow and requiring too many participants. "We can approve drugs for very tiny patient populations, even at the level of the individual," he said, while emphasizing the need for safety. But Platanias thinks the FDA has become much more flexible in recent years. In the cancer field, at least, "You now see faster approvals for more drugs. Having [more] shortcuts on clinical trial approvals is not necessarily a good idea."

With so many options on the table, ARPA-H needs to show the public a clear framework for measuring the value of potential projects. Kass warned that well-resourced advocates could skew the agency's priorities. They've affected health outcomes before, she noted; fundraising may partly explain larger increases in life expectancy for cystic fibrosis than sickle cell anemia. Engaging diverse communities is a must for ARPA-H. So are partnerships to get the agency's outputs to people who need them. "Research is half the equation," said Kass. "If we don't ensure implementation and access, who cares." The White House concept paper on ARPA-H made a similar point.

As Congress works on authorizing ARPA-H this year, Might is doing what he can to ensure better access to innovation on a patient-by-patient basis. Last year, his son, Bertrand, passed away suddenly from his disorder. He was 12. But Might's sense of urgency has persisted, as he directs the Precision Medicine Institute at the University of Alabama-Birmingham. That urgency "can be carried into an agency like ARPA-H," he said. "It guides what I do as I apply for funding, because I'm trying to build the infrastructure that other parents need. So they don't have to build it from scratch like I did."

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

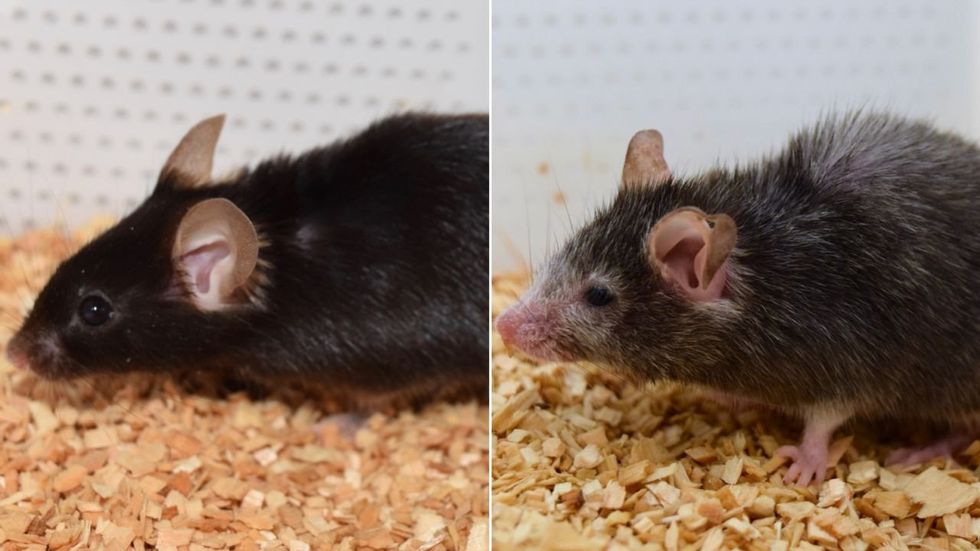

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School