The Voice Behind Some of Your Favorite Cartoon Characters Helped Create the Artificial Heart

This Jarvik-7 artificial heart was used in the first bridge operation in 1985 meant to replace a failing heart while the patient waited for a donor organ.

In June, a team of surgeons at Duke University Hospital implanted the latest model of an artificial heart in a 39-year-old man with severe heart failure, a condition in which the heart doesn't pump properly. The man's mechanical heart, made by French company Carmat, is a new generation artificial heart and the first of its kind to be transplanted in the United States. It connects to a portable external power supply and is designed to keep the patient alive until a replacement organ becomes available.

Many patients die while waiting for a heart transplant, but artificial hearts can bridge the gap. Though not a permanent solution for heart failure, artificial hearts have saved countless lives since their first implantation in 1982.

What might surprise you is that the origin of the artificial heart dates back decades before, when an inventive television actor teamed up with a famous doctor to design and patent the first such device.

A man of many talents

Paul Winchell was an entertainer in the 1950s and 60s, rising to fame as a ventriloquist and guest-starring as an actor on programs like "The Ed Sullivan Show" and "Perry Mason." When children's animation boomed in the 1960s, Winchell made a name for himself as a voice actor on shows like "The Smurfs," "Winnie the Pooh," and "The Jetsons." He eventually became famous for originating the voices of Tigger from "Winnie the Pooh" and Gargamel from "The Smurfs," among many others.

But Winchell wasn't just an entertainer: He also had a quiet passion for science and medicine. Between television gigs, Winchell busied himself working as a medical hypnotist and acupuncturist, treating the same Hollywood stars he performed alongside. When he wasn't doing that, Winchell threw himself into engineering and design, building not only the ventriloquism dummies he used on his television appearances but a host of products he'd dreamed up himself. Winchell spent hours tinkering with his own inventions, such as a set of battery-powered gloves and something called a "flameless lighter." Over the course of his life, Winchell designed and patented more than 30 of these products – mostly novelties, but also serious medical devices, such as a portable blood plasma defroster.

| Ventriloquist Paul Winchell with Jerry Mahoney, his dummy, in 1951 |

A meeting of the minds

In the early 1950s, Winchell appeared on a variety show called the "Arthur Murray Dance Party" and faced off in a dance competition with the legendary Ricardo Montalban (Winchell won). At a cast party for the show later that same night, Winchell met Dr. Henry Heimlich – the same doctor who would later become famous for inventing the Heimlich maneuver, who was married to Murray's daughter. The two hit it off immediately, bonding over their shared interest in medicine. Before long, Heimlich invited Winchell to come observe him in the operating room at the hospital where he worked. Winchell jumped at the opportunity, and not long after he became a frequent guest in Heimlich's surgical theatre, fascinated by the mechanics of the human body.

One day while Winchell was observing at the hospital, he witnessed a patient die on the operating table after undergoing open-heart surgery. He was suddenly struck with an idea: If there was some way doctors could keep blood pumping temporarily throughout the body during surgery, patients who underwent risky operations like open-heart surgery might have a better chance of survival. Winchell rushed to Heimlich with the idea – and Heimlich agreed to advise Winchell and look over any design drafts he came up with. So Winchell went to work.

Winchell's heart

As it turned out, building ventriloquism dummies wasn't that different from building an artificial heart, Winchell noted later in his autobiography – the shifting valves and chambers of the mechanical heart were similar to the moving eyes and opening mouths of his puppets. After each design, Winchell would go back to Heimlich and the two would confer, making adjustments along the way to.

By 1956, Winchell had perfected his design: The "heart" consisted of a bag that could be placed inside the human body, connected to a battery-powered motor outside of the body. The motor enabled the bag to pump blood throughout the body, similar to a real human heart. Winchell received a patent for the design in 1963.

At the time, Winchell never quite got the credit he deserved. Years later, researchers at the University of Utah, working on their own artificial heart, came across Winchell's patent and got in touch with Winchell to compare notes. Winchell ended up donating his patent to the team, which included Dr. Richard Jarvik. Jarvik expanded on Winchell's design and created the Jarvik-7 – the world's first artificial heart to be successfully implanted in a human being in 1982.

The Jarvik-7 has since been replaced with newer, more efficient models made up of different synthetic materials, allowing patients to live for longer stretches without the heart clogging or breaking down. With each new generation of hearts, heart failure patients have been able to live relatively normal lives for longer periods of time and with fewer complications than before – and it never would have been possible without the unsung genius of a puppeteer and his love of science.

Out of Thin Air: A Fresh Solution to Farming’s Water Shortages

Dry, arid and remote farming regions are vulnerable to water shortages, but scientists are working on a promising new solution.

California has been plagued by perilous droughts for decades. Freshwater shortages have sparked raging wildfires and killed fruit and vegetable crops. And California is not alone in its danger of running out of water for farming; parts of the Southwest, including Texas, are battling severe drought conditions, according to the North American Drought Monitor. These two states account for 316,900 of the 2 million total U.S. farms.

But even as farming becomes more vulnerable due to water shortages, the world's demand for food is projected to increase 70 percent by 2050, according to Guihua Yu, an associate professor of materials science at The University of Texas at Austin.

"Water is the most limiting natural resource for agricultural production because of the freshwater shortage and enormous water consumption needed for irrigation," Yu said.

As scientists have searched for solutions, an alternative water supply has been hiding in plain sight: Water vapor in the atmosphere. It is abundant, available, and endlessly renewable, just waiting for the moment that technological innovation and necessity converged to make it fit for use. Now, new super-moisture-absorbent gels developed by Yu and a team of researchers can pull that moisture from the air and bring it into soil, potentially expanding the map of farmable land around the globe to dry and remote regions that suffer from water shortages.

"This opens up opportunities to turn those previously poor-quality or inhospitable lands to become useable and without need of centralized water and power supplies," Yu said.

A renewable source of freshwater

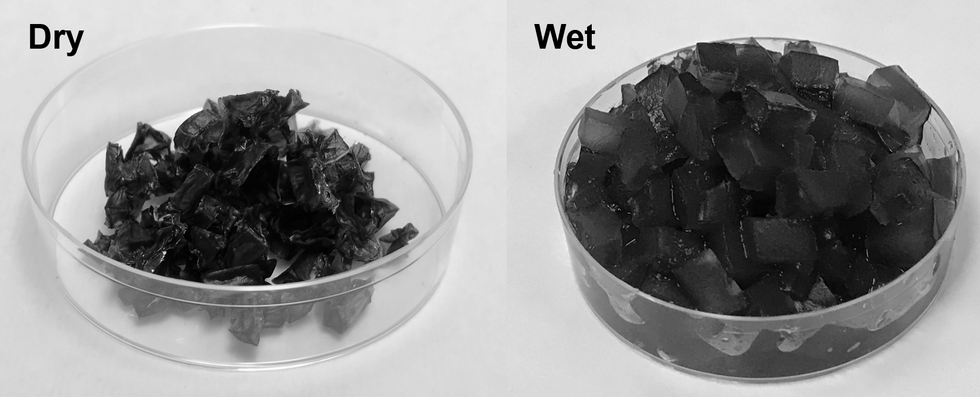

The hydrogels are a gelatin-like substance made from synthetic materials. The gels activate in cooler, humid overnight periods and draw water from the air. During a four-week experiment, Yu's team observed that soil with these gels provided enough water to support seed germination and plant growth without an additional liquid water supply. And the soil was able to maintain the moist environment for more than a month, according to Yu.

The super absorbent gels developed at the University of Texas at Austin.

Xingyi Zhou, UT Austin

"It is promising to liberate underdeveloped and drought areas from the long-distance water and power supplies for agricultural production," Yu said.

Crops also rely on fertilizer to maintain soil fertility and increase the production yield, but it is easily lost through leaching. Runoff increases agricultural costs and contributes to environmental pollution. The interaction between the gels and agrochemicals offer slow and controlled fertilizer release to maintain the balance between the root of the plant and the soil.

The possibilities are endless

Harvesting atmospheric water is exciting on multiple fronts. The super-moisture-absorbent gel can also be used for passively cooling solar panels. Solar radiation is the magic behind the process. Overnight, as temperatures cool, the gels absorb water hanging in the atmosphere. The moisture is stored inside the gels until the thermometer rises. Heat from the sun serves as the faucet that turns the gels on so they can release the stored water and cool down the panels. Effective cooling of the solar panels is important for sustainable long-term power generation.

In addition to agricultural uses and cooling for energy devices, atmospheric water harvesting technologies could even reach people's homes.

"They could be developed to enable easy access to drinking water through individual systems for household usage," Yu said.

Next steps

Yu and the team are now focused on affordability and developing practical applications for use. The goal is to optimize the gel materials to achieve higher levels of water uptake from the atmosphere.

"We are exploring different kinds of polymers and solar absorbers while exploring low-cost raw materials for production," Yu said.

The ability to transform atmospheric water vapor into a cheap and plentiful water source would be a game-changer. One day in the not-too-distant future, if climate change intensifies and droughts worsen, this innovation may become vital to our very survival.

On left, people excitedly line up for Salk's polio vaccine in 1957; on right, Joe Biden gets one of the COVID vaccines on December 21, 2020.

On the morning of April 12, 1955, newsrooms across the United States inked headlines onto newsprint: the Salk Polio vaccine was "safe, effective, and potent." This was long-awaited news. Americans had limped through decades of fear, unaware of what caused polio or how to cure it, faced with the disease's terrifying, visible power to paralyze and kill, particularly children.

The announcement of the polio vaccine was celebrated with noisy jubilation: church bells rang, factory whistles sounded, people wept in the streets. Within weeks, mass inoculation began as the nation put its faith in a vaccine that would end polio.

Today, most of us are blissfully ignorant of child polio deaths, making it easier to believe that we have not personally benefited from the development of vaccines. According to Dr. Steven Pinker, cognitive psychologist and author of the bestselling book Enlightenment Now, we've become blasé to the gifts of science. "The default expectation is not that disease is part of life and science is a godsend, but that health is the default, and any disease is some outrage," he says.

We're now in the early stages of another vaccine rollout, one we hope will end the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. And yet, the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines are met with far greater hesitancy and skepticism than the polio vaccine was in the 50s.

In 2021, concerns over the speed and safety of vaccine development and technology plague this heroic global effort, but the roots of vaccine hesitancy run far deeper. Vaccine hesitancy has always existed in the U.S., even in the polio era, motivated in part by fears around "living virus" in a bad batch of vaccines produced by Cutter Laboratories in 1955. But in the last half century, we've witnessed seismic cultural shifts—loss of public trust, a rise in misinformation, heightened racial and socioeconomic inequality, and political polarization have all intensified vaccine-related fears and resistance. Making sense of how we got here may help us understand how to move forward.

The Rise and Fall of Public Trust

When the polio vaccine was released in 1955, "we were nearing an all-time high point in public trust," says Matt Baum, Harvard Kennedy School professor and lead author of several reports measuring public trust and vaccine confidence. Baum explains that the U.S. was experiencing a post-war boom following the Allied triumph in WWII, a popular Roosevelt presidency, and the rapid innovation that elevated the country to an international superpower.

The 1950s witnessed the emergence of nuclear technology, a space program, and unprecedented medical breakthroughs, adds Emily Brunson, Texas State University anthropologist and co-chair of the Working Group on Readying Populations for COVID-19 Vaccine. "Antibiotics were a game changer," she states. While before, people got sick with pneumonia for a month, suddenly they had access to pills that accelerated recovery.

During this period, science seemed to hold all the answers; people embraced the idea that we could "come to know the world with an absolute truth," Brunson explains. Doctors were portrayed as unquestioned gods, so Americans were primed to trust experts who told them the polio vaccine was safe.

"The emotional tone of the news has gone downward since the 1940s, and journalists consider it a professional responsibility to cover the negative."

That blind acceptance eroded in the 1960s and 70s as people came to understand that science can be inherently political. "Getting to an absolute truth works out great for white men, but these things affect people socially in radically different ways," Brunson says. As the culture began questioning the white, patriarchal biases of science, doctors lost their god-like status and experts were pushed off their pedestals. This trend continues with greater intensity today, as President Trump has led a campaign against experts and waged a war on science that began long before the pandemic.

The Shift in How We Consume Information

In the 1950s, the media created an informational consensus. The fundamental ideas the public consumed about the state of the world were unified. "People argued about the best solutions, but didn't fundamentally disagree on the factual baseline," says Baum. Indeed, the messaging around the polio vaccine was centralized and consistent, led by President Roosevelt's successful March of Dimes crusade. People of lower socioeconomic status with limited access to this information were less likely to have confidence in the vaccine, but most people consumed media that assured them of the vaccine's safety and mobilized them to receive it.

Today, the information we consume is no longer centralized—in fact, just the opposite. "When you take that away, it's hard for people to know what to trust and what not to trust," Baum explains. We've witnessed an increase in polarization and the technology that makes it easier to give people what they want to hear, reinforcing the human tendencies to vilify the other side and reinforce our preexisting ideas. When information is engineered to further an agenda, each choice and risk calculation made while navigating the COVID-19 pandemic is deeply politicized.

This polarization maps onto a rise in socioeconomic inequality and economic uncertainty. These factors, associated with a sense of lost control, prime people to embrace misinformation, explains Baum, especially when the situation is difficult to comprehend. "The beauty of conspiratorial thinking is that it provides answers to all these questions," he says. Today's insidious fragmentation of news media accelerates the circulation of mis- and disinformation, reaching more people faster, regardless of veracity or motivation. In the case of vaccines, skepticism around their origin, safety, and motivation is intensified.

Alongside the rise in polarization, Pinker says "the emotional tone of the news has gone downward since the 1940s, and journalists consider it a professional responsibility to cover the negative." Relentless focus on everything that goes wrong further erodes public trust and paints a picture of the world getting worse. "Life saved is not a news story," says Pinker, but perhaps it should be, he continues. "If people were more aware of how much better life was generally, they might be more receptive to improvements that will continue to make life better. These improvements don't happen by themselves."

The Future Depends on Vaccine Confidence

So far, the U.S. has been unable to mitigate the catastrophic effects of the pandemic through social distancing, testing, and contact tracing. President Trump has downplayed the effects and threat of the virus, censored experts and scientists, given up on containing the spread, and mobilized his base to protest masks. The Trump Administration failed to devise a national plan, so our national plan has defaulted to hoping for the "miracle" of a vaccine. And they are "something of a miracle," Pinker says, describing vaccines as "the most benevolent invention in the history of our species." In record-breaking time, three vaccines have arrived. But their impact will be weakened unless we achieve mass vaccination. As Brunson notes, "The technology isn't the fix; it's people taking the technology."

Significant challenges remain, including facilitating widespread access and supporting on-the-ground efforts to allay concerns and build trust with specific populations with historic reasons for distrust, says Brunson. Baum predicts continuing delays as well as deaths from other causes that will be linked to the vaccine.

Still, there's every reason for hope. The new administration "has its eyes wide open to these challenges. These are the kind of problems that are amenable to policy solutions if we have the will," Baum says. He forecasts widespread vaccination by late summer and a bounce back from the economic damage, a "Good News Story" that will bolster vaccine acceptance in the future. And Pinker reminds us that science, medicine, and public health have greatly extended our lives in the last few decades, a trend that can only continue if we're willing to roll up our sleeves.