Scientists Are Devising Clever Solutions to Feed Astronauts on Mars Space Flights

Astronaut and Expedition 64 Flight Engineer Soichi Noguchi of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency displays Extra Dwarf Pak Choi plants growing aboard the International Space Station. The plants were grown for the Veggie study which is exploring space agriculture as a way to sustain astronauts on future missions to the Moon or Mars.

Astronauts at the International Space Station today depend on pre-packaged, freeze-dried food, plus some fresh produce thanks to regular resupply missions. This supply chain, however, will not be available on trips further out, such as the moon or Mars. So what are astronauts on long missions going to eat?

Going by the options available now, says Christel Paille, an engineer at the European Space Agency, a lunar expedition is likely to have only dehydrated foods. “So no more fresh product, and a limited amount of already hydrated product in cans.”

For the Mars mission, the situation is a bit more complex, she says. Prepackaged food could still constitute most of their food, “but combined with [on site] production of certain food products…to get them fresh.” A Mars mission isn’t right around the corner, but scientists are currently working on solutions for how to feed those astronauts. A number of boundary-pushing efforts are now underway.

The logistics of growing plants in space, of course, are very different from Earth. There is no gravity, sunlight, or atmosphere. High levels of ionizing radiation stunt plant growth. Plus, plants take up a lot of space, something that is, ironically, at a premium up there. These and special nutritional requirements of spacefarers have given scientists some specific and challenging problems.

To study fresh food production systems, NASA runs the Vegetable Production System (Veggie) on the ISS. Deployed in 2014, Veggie has been growing salad-type plants on “plant pillows” filled with growth media, including a special clay and controlled-release fertilizer, and a passive wicking watering system. They have had some success growing leafy greens and even flowers.

"Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources."

A larger farming facility run by NASA on the ISS is the Advanced Plant Habitat to study how plants grow in space. This fully-automated, closed-loop system has an environmentally controlled growth chamber and is equipped with sensors that relay real-time information about temperature, oxygen content, and moisture levels back to the ground team at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. In December 2020, the ISS crew feasted on radishes grown in the APH.

“But salad doesn’t give you any calories,” says Erik Seedhouse, a researcher at the Applied Aviation Sciences Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “It gives you some minerals, but it doesn’t give you a lot of carbohydrates.” Seedhouse also noted in his 2020 book Life Support Systems for Humans in Space: “Integrating the growing of plants into a life support system is a fiendishly difficult enterprise.” As a case point, he referred to the ESA’s Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) program that has been running since 1989 to integrate growing of plants in a closed life support system such as a spacecraft.

Paille, one of the scientists running MELiSSA, says that the system aims to recycle the metabolic waste produced by crew members back into the metabolic resources required by them: “The aim is…to come [up with] a closed, sustainable system which does not [need] any logistics resupply.” MELiSSA uses microorganisms to process human excretions in order to harvest carbon dioxide and nitrate to grow plants. “Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources,” Paille adds.

Microorganisms play a big role as “fuel” in food production in extreme places, including in space. Last year, researchers discovered Methylobacterium strains on the ISS, including some never-seen-before species. Kasthuri Venkateswaran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, one of the researchers involved in the study, says, “[The] isolation of novel microbes that help to promote the plant growth under stressful conditions is very essential… Certain bacteria can decompose complex matter into a simple nutrient [that] the plants can absorb.” These microbes, which have already adapted to space conditions—such as the absence of gravity and increased radiation—boost various plant growth processes and help withstand the harsh physical environment.

MELiSSA, says Paille, has demonstrated that it is possible to grow plants in space. “This is important information because…we didn’t know whether the space environment was affecting the biological cycle of the plant…[and of] cyanobacteria.” With the scientific and engineering aspects of a closed, self-sustaining life support system becoming clearer, she says, the next stage is to find out if it works in space. They plan to run tests recycling human urine into useful components, including those that promote plant growth.

The MELiSSA pilot plant uses rats currently, and needs to be translated for human subjects for further studies. “Demonstrating the process and well-being of a rat in terms of providing water, sufficient oxygen, and recycling sufficient carbon dioxide, in a non-stressful manner, is one thing,” Paille says, “but then, having a human in the loop [means] you also need to integrate user interfaces from the operational point of view.”

Growing food in space comes with an additional caveat that underscores its high stakes. Barbara Demmig-Adams from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado Boulder explains, “There are conditions that actually will hurt your health more than just living here on earth. And so the need for nutritious food and micronutrients is even greater for an astronaut than for [you and] me.”

Demmig-Adams, who has worked on increasing the nutritional quality of plants for long-duration spaceflight missions, also adds that there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Her work has focused on duckweed, a rather unappealingly named aquatic plant. “It is 100 percent edible, grows very fast, it’s very small, and like some other floating aquatic plants, also produces a lot of protein,” she says. “And here on Earth, studies have shown that the amount of protein you get from the same area of these floating aquatic plants is 20 times higher compared to soybeans.”

Aquatic plants also tend to grow well in microgravity: “Plants that float on water, they don’t respond to gravity, they just hug the water film… They don’t need to know what’s up and what’s down.” On top of that, she adds, “They also produce higher concentrations of really important micronutrients, antioxidants that humans need, especially under space radiation.” In fact, duckweed, when subjected to high amounts of radiation, makes nutrients called carotenoids that are crucial for fighting radiation damage. “We’ve looked at dozens and dozens of plants, and the duckweed makes more of this radiation fighter…than anything I’ve seen before.”

Despite all the scientific advances and promising leads, no one really knows what the conditions so far out in space will be and what new challenges they will bring. As Paille says, “There are known unknowns and unknown unknowns.”

One definite “known” for astronauts is that growing their food is the ideal scenario for space travel in the long term since “[taking] all your food along with you, for best part of two years, that’s a lot of space and a lot of weight,” as Seedhouse says. That said, once they land on Mars, they’d have to think about what to eat all over again. “Then you probably want to start building a greenhouse and growing food there [as well],” he adds.

And that is a whole different challenge altogether.

As We Wait for a Vaccine, Scientists Work to Scale Up the Best COVID-19 Antibodies to Give New Patients

In this illustration of immune defense, Y-shaped proteins called antibodies attack a virus.

When we get sick, our immune system sends its soldier cells to the battlefield. Called B-cells, they "examine" the foreign particles that shouldn't be in our bloodstream—and start producing the antibodies, the proteins to neutralize the invaders.

To screen the antibodies, scientists have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

The better these antibodies are at neutralizing the pathogen, the faster we recover.

The antibodies acquired from COVID-19 survivors already showed promise in treating other patients, but because they must be obtained from people, generating a regular supply is not feasible. To close the gap, researchers are trying to identify the B-cells that make the best antibodies—and then farm them in laboratories at scale.

Scientists at Berkley Lights, a biotechnology company in California, have been screening B-cells from recovered patients and testing the antibodies they release for virus-neutralizing abilities. To screen the antibodies, scientists there have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

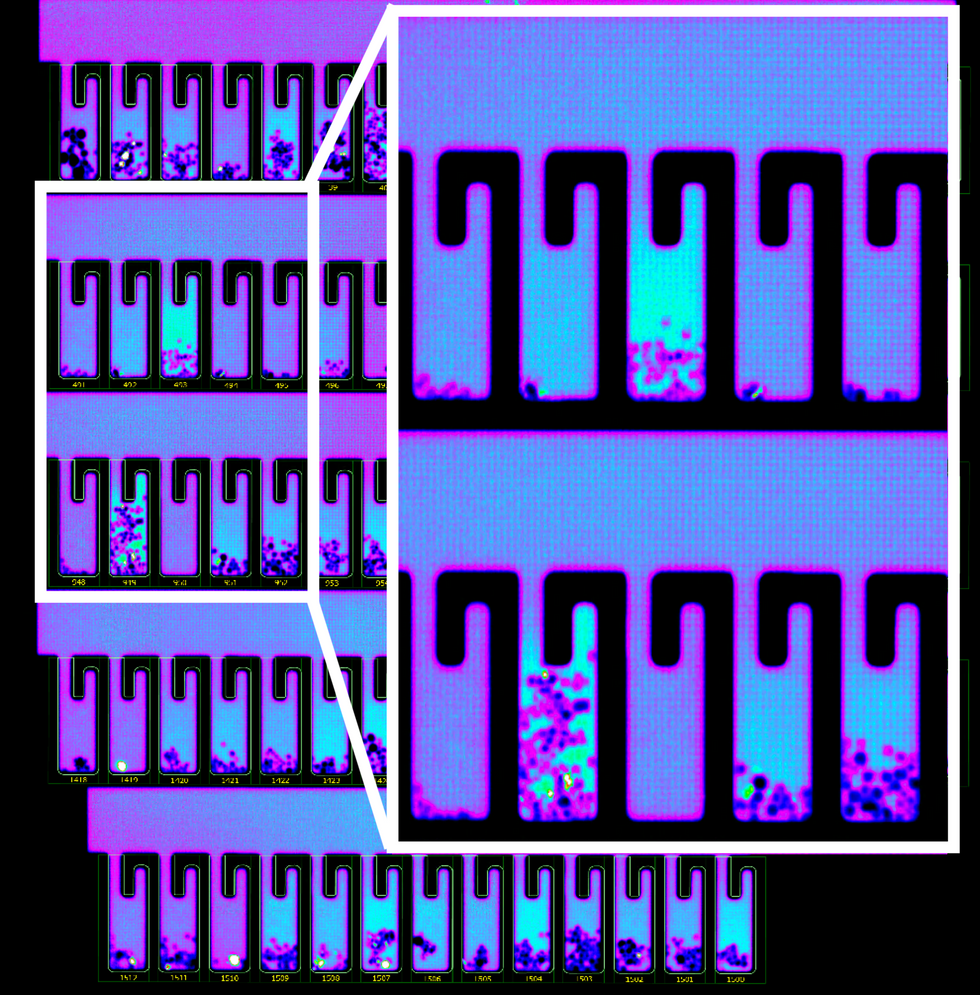

So how does it work? First, the individual B-cells are placed into microscopic chambers called nano-pens, where they secrete the antibodies. Once released, the antibodies are flushed over tiny beads that have bits of the viral particles attached to them, along with special molecules that can emit fluorescent light.

"When an antibody binds to the bead, we see a bright light on the bead," explains John Proctor, the company's senior vice president of antibody therapeutics. "So we can identify which cells are making the antibodies."

Then the antibodies are tested for their ability to counteract the coronavirus's spike proteins, which the virus uses to break into our cells. Not all antibodies are equally good at this crucial defense move—some can block only parts of the virus's machinery, while others can neutralize it completely. Proctor and his colleagues are looking for the latter.

Once scientists identify the best performing B-cells, they crack the cells open—or in scientific terms "lyse" them—and extract the genetic instructions for making the antibodies. As it turns out, B-cells aren't very efficient at pumping out massive amounts of antibodies, so scientists insert these genetic instructions into a different, more prolific type of cell.

Named Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells or CHO, these cells are commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry because they can generate therapeutic proteins en masse. Under the right nutrient conditions, which include a lot of sugar, CHO cells can keep making the antibodies at commercial levels. "They are engineered to operate in very large bioreactors," Proctor explains.

While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours.

Berkeley Lights' technology has already been used to screen the antibodies of recovered patients from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In another example, a biotech company GenScript ProBio used the platform to screen mice engineered to have human antibodies for the coronavirus.

In addition to its small, lab-on-a-chip size, Berkeley Lights' system allows scientists to greatly speed up the screening process. While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours. "We only need one B-cell per pen and a couple of beads to see that fluorescent signal," Proctor says. "It is a more advanced way to process and analyze cells, and that level of sensitivity is unique to our technology."

B-cells secreting antibodies inside the Berkeley Lights Beacon System Nano-Pens.

While vaccines are likely to take months to develop and test, antibodies might arrive to the battleground sooner. With the extremely limited treatment options for COVID-19, antibody-based therapeutics can potentially bridge this gap.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

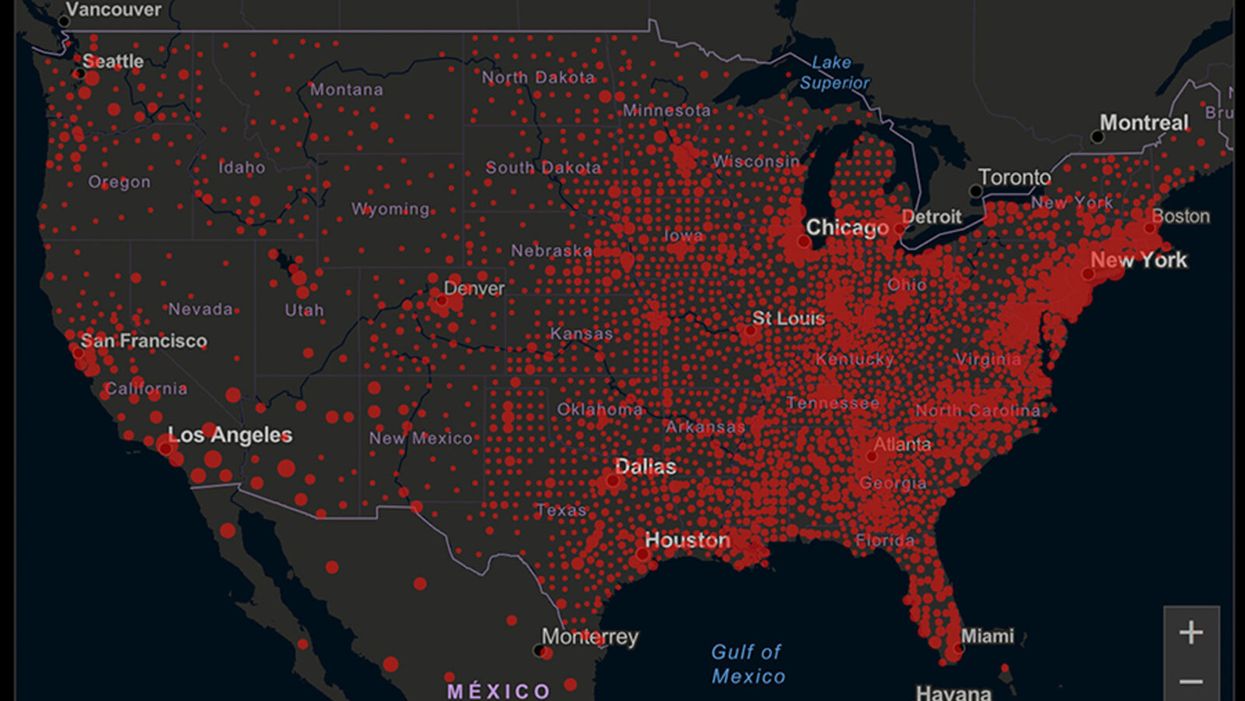

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."