Scientists Are Devising Clever Solutions to Feed Astronauts on Mars Space Flights

Astronaut and Expedition 64 Flight Engineer Soichi Noguchi of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency displays Extra Dwarf Pak Choi plants growing aboard the International Space Station. The plants were grown for the Veggie study which is exploring space agriculture as a way to sustain astronauts on future missions to the Moon or Mars.

Astronauts at the International Space Station today depend on pre-packaged, freeze-dried food, plus some fresh produce thanks to regular resupply missions. This supply chain, however, will not be available on trips further out, such as the moon or Mars. So what are astronauts on long missions going to eat?

Going by the options available now, says Christel Paille, an engineer at the European Space Agency, a lunar expedition is likely to have only dehydrated foods. “So no more fresh product, and a limited amount of already hydrated product in cans.”

For the Mars mission, the situation is a bit more complex, she says. Prepackaged food could still constitute most of their food, “but combined with [on site] production of certain food products…to get them fresh.” A Mars mission isn’t right around the corner, but scientists are currently working on solutions for how to feed those astronauts. A number of boundary-pushing efforts are now underway.

The logistics of growing plants in space, of course, are very different from Earth. There is no gravity, sunlight, or atmosphere. High levels of ionizing radiation stunt plant growth. Plus, plants take up a lot of space, something that is, ironically, at a premium up there. These and special nutritional requirements of spacefarers have given scientists some specific and challenging problems.

To study fresh food production systems, NASA runs the Vegetable Production System (Veggie) on the ISS. Deployed in 2014, Veggie has been growing salad-type plants on “plant pillows” filled with growth media, including a special clay and controlled-release fertilizer, and a passive wicking watering system. They have had some success growing leafy greens and even flowers.

"Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources."

A larger farming facility run by NASA on the ISS is the Advanced Plant Habitat to study how plants grow in space. This fully-automated, closed-loop system has an environmentally controlled growth chamber and is equipped with sensors that relay real-time information about temperature, oxygen content, and moisture levels back to the ground team at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. In December 2020, the ISS crew feasted on radishes grown in the APH.

“But salad doesn’t give you any calories,” says Erik Seedhouse, a researcher at the Applied Aviation Sciences Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “It gives you some minerals, but it doesn’t give you a lot of carbohydrates.” Seedhouse also noted in his 2020 book Life Support Systems for Humans in Space: “Integrating the growing of plants into a life support system is a fiendishly difficult enterprise.” As a case point, he referred to the ESA’s Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) program that has been running since 1989 to integrate growing of plants in a closed life support system such as a spacecraft.

Paille, one of the scientists running MELiSSA, says that the system aims to recycle the metabolic waste produced by crew members back into the metabolic resources required by them: “The aim is…to come [up with] a closed, sustainable system which does not [need] any logistics resupply.” MELiSSA uses microorganisms to process human excretions in order to harvest carbon dioxide and nitrate to grow plants. “Ideally, we would like a system which has zero waste and, therefore, needs zero input, zero additional resources,” Paille adds.

Microorganisms play a big role as “fuel” in food production in extreme places, including in space. Last year, researchers discovered Methylobacterium strains on the ISS, including some never-seen-before species. Kasthuri Venkateswaran of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, one of the researchers involved in the study, says, “[The] isolation of novel microbes that help to promote the plant growth under stressful conditions is very essential… Certain bacteria can decompose complex matter into a simple nutrient [that] the plants can absorb.” These microbes, which have already adapted to space conditions—such as the absence of gravity and increased radiation—boost various plant growth processes and help withstand the harsh physical environment.

MELiSSA, says Paille, has demonstrated that it is possible to grow plants in space. “This is important information because…we didn’t know whether the space environment was affecting the biological cycle of the plant…[and of] cyanobacteria.” With the scientific and engineering aspects of a closed, self-sustaining life support system becoming clearer, she says, the next stage is to find out if it works in space. They plan to run tests recycling human urine into useful components, including those that promote plant growth.

The MELiSSA pilot plant uses rats currently, and needs to be translated for human subjects for further studies. “Demonstrating the process and well-being of a rat in terms of providing water, sufficient oxygen, and recycling sufficient carbon dioxide, in a non-stressful manner, is one thing,” Paille says, “but then, having a human in the loop [means] you also need to integrate user interfaces from the operational point of view.”

Growing food in space comes with an additional caveat that underscores its high stakes. Barbara Demmig-Adams from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado Boulder explains, “There are conditions that actually will hurt your health more than just living here on earth. And so the need for nutritious food and micronutrients is even greater for an astronaut than for [you and] me.”

Demmig-Adams, who has worked on increasing the nutritional quality of plants for long-duration spaceflight missions, also adds that there is no need to reinvent the wheel. Her work has focused on duckweed, a rather unappealingly named aquatic plant. “It is 100 percent edible, grows very fast, it’s very small, and like some other floating aquatic plants, also produces a lot of protein,” she says. “And here on Earth, studies have shown that the amount of protein you get from the same area of these floating aquatic plants is 20 times higher compared to soybeans.”

Aquatic plants also tend to grow well in microgravity: “Plants that float on water, they don’t respond to gravity, they just hug the water film… They don’t need to know what’s up and what’s down.” On top of that, she adds, “They also produce higher concentrations of really important micronutrients, antioxidants that humans need, especially under space radiation.” In fact, duckweed, when subjected to high amounts of radiation, makes nutrients called carotenoids that are crucial for fighting radiation damage. “We’ve looked at dozens and dozens of plants, and the duckweed makes more of this radiation fighter…than anything I’ve seen before.”

Despite all the scientific advances and promising leads, no one really knows what the conditions so far out in space will be and what new challenges they will bring. As Paille says, “There are known unknowns and unknown unknowns.”

One definite “known” for astronauts is that growing their food is the ideal scenario for space travel in the long term since “[taking] all your food along with you, for best part of two years, that’s a lot of space and a lot of weight,” as Seedhouse says. That said, once they land on Mars, they’d have to think about what to eat all over again. “Then you probably want to start building a greenhouse and growing food there [as well],” he adds.

And that is a whole different challenge altogether.

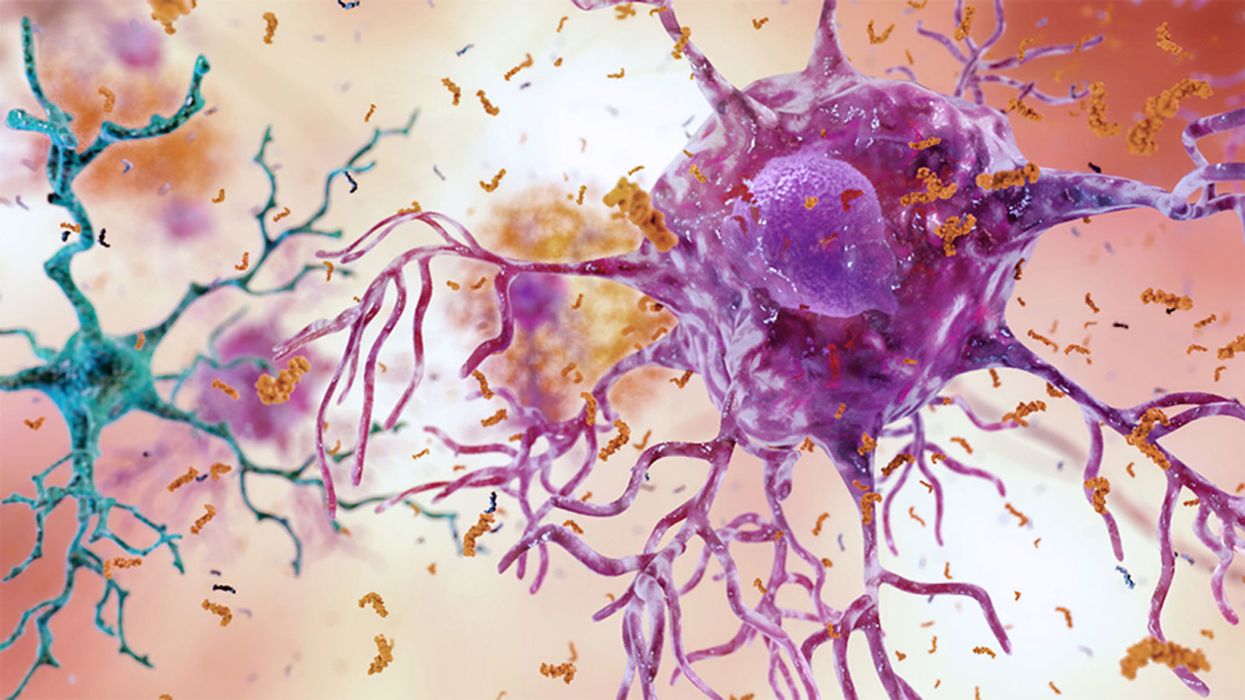

A Mother-and-Daughter Team Have Developed What May Be the World’s First Alzheimer’s Vaccine

Brain inflammation from Alzheimer's disease.

Alzheimer's is a terrible disease that robs a person of their personality and memory before eventually leading to death. It's the sixth-largest killer in the U.S. and, currently, there are 5.8 million Americans living with the disease.

Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

It devastates people and families and it's estimated that Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia will cost the U.S. $290 billion dollars this year alone. It's estimated that it will become a trillion-dollar-a-year disease by 2050.

There have been over 200 unsuccessful attempts to find a cure for the disease and the clinical trial termination rate is 98 percent.

Alzheimer's is caused by plaque deposits that develop in brain tissue that become toxic to brain cells. One of the major hurdles to finding a cure for the disease is that it's impossible to clear out the deposits from the tissue. So scientists have turned their attention to early detection and prevention.

One very encouraging development has come out of the work done by Dr. Chang Yi Wang, PhD. Wang is a prolific bio-inventor; one of her biggest successes is developing a foot-and-mouth vaccine for pigs that has been administered more than three billion times.

Mei Mei Hu

Brainstorm Health / Flickr.

In January, United Neuroscience, a biotech company founded by Yi, her daughter Mei Mei Hu, and son-in-law, Louis Reese, announced the first results from a phase IIa clinical trial on UB-311, an Alzheimer's vaccine.

The vaccine has synthetic versions of amino acid chains that trigger antibodies to attack Alzheimer's protein the blood. Wang's vaccine is a significant improvement over previous attempts because it can attack the Alzheimer's protein without creating any adverse side effects.

"We were able to generate some antibodies in all patients, which is unusual for vaccines," Yi told Wired. "We're talking about almost a 100 percent response rate. So far, we have seen an improvement in three out of three measurements of cognitive performance for patients with mild Alzheimer's disease."

The researchers also claim it can delay the onset of the disease by five years. While this would be a godsend for people with the disease and their families, according to Elle, it could also save Medicare and Medicaid more than $220 billion.

"You'd want to see larger numbers, but this looks like a beneficial treatment," James Brown, director of the Aston University Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, told Wired. "This looks like a silver bullet that can arrest or improve symptoms and, if it passes the next phase, it could be the best chance we've got."

"A word of caution is that it's a small study," says Drew Holzapfel, acting president of the nonprofit UsAgainstAlzheimer's, said according to Elle. "But the initial data is compelling."

The company is now working on its next clinical trial of the vaccine and while hopes are high, so is the pressure. The company has already invested $100 million developing its vaccine platform. According to Reese, the company's ultimate goal is to create a host of vaccines that will be administered to protect people from chronic illness.

"We have a 50-year vision -- to immuno-sculpt people against chronic illness and chronic aging with vaccines as prolific as vaccines for infectious diseases," he told Elle.

[Editor's Note: This article was originally published by Upworthy here and has been republished with permission.]

Turning Algae Into Environmentally Friendly Fuel Just Got Faster and Smarter

Algae in the Mediterranean sea.

Was your favorite beach closed this summer? Algae blooms are becoming increasingly the reason to blame and, as the climate heats up, scientists say we can expect more of the warm water-loving blue-green algae to grow.

"We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter."

Oddly enough, the pesky growth could help fuel our carbon-friendly options.

This year, the University of Utah scientists discovered a faster way to turn algae into fuel. Algae is filled with lipids that we can feed our energy-hungry diesel engines. The problem is extracting the lipids, which usually requires more energy to transform than the actual energy we'd get – not achieving what scientists call "energy parity."

But now, the University of Utah team has discovered a new mix that is more efficient and much faster. We can now extract more power from algae with less waste materials after the fact. Paper co-author Dr. Leonard Pease says, "We have removed a significant development barrier to make algal biofuel production more efficient and smarter. Our method puts us much closer to creating biofuels energy parity than we were before."

Next Up

Algae has a lot going for it as an alternative fuel source. It grows fast and easily, absorbs carbon dioxide, does not compete with food crops for land, and could produce up to 60 times more oil than standard land-based energy crops, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Yet the costs of algal biofuel production are still expensive for now.

According to Science Daily, only about five percent of total primary energy use in the United States came from algae and other biomass forms. By making the process more efficient, America and other nations could potentially begin relying on more plentiful resources – which, ironically, are more common now because of climate change.

Algae fuel efficiency is already a proven concept. A decade ago, Continental Airlines completed a 90-minute Boeing 737-800 flight with one engine split between biofuel and aircraft fuel. The biofuel was straight from algae. (Other flights were done based on nut fuel and other alternative sources.) The commercial airplane required no modification to the engine and the biofuel itself exceeded the standards of traditional jet fuel.

The problem, as noted at the time, is that biofuels derived from algae had yet to be proven as "commercially competitive."

The University of Utah's discovery could mean cheaper processing. At this point, it is less about if it works and more about if it is a practical alternative.

However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever.

Open Questions

Higher efficiency and simpler transformations could mean lower prices and more business access. However, it's unclear how long it will take for algae to become more mainstream, if ever. The algae biofuel worked great for a relatively sophisticated Boeing 737 engine, but your family car, the cross-country delivery trucks and other less powerful machines may need to be modified – and that means the industry-at-large would have to revise their products in order to support the change.

Future-focused groups are already looking at how algae can fuel our space programs, especially if it is more renewable, safe and, potentially, cheaper than our traditional fuel choices. But first, it is worth waiting and seeing if corporations and, later, citizens are willing to take the plunge.