Bad Actors Getting Your Health Data Is the FBI’s Latest Worry

A hacker activating a 3D rendering of DNA data.

In February 2015, the health insurer Anthem revealed that criminal hackers had gained access to the company's servers, exposing the personal information of nearly 79 million patients. It's the largest known healthcare breach in history.

FBI agents worry that the vast amounts of healthcare data being generated for precision medicine efforts could leave the U.S. vulnerable to cyber and biological attacks.

That year, the data of millions more would be compromised in one cyberattack after another on American insurers and other healthcare organizations. In fact, for the past several years, the number of reported data breaches has increased each year, from 199 in 2010 to 344 in 2017, according to a September 2018 analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The FBI's Edward You sees this as a worrying trend. He says hackers aren't just interested in your social security or credit card number. They're increasingly interested in stealing your medical information. Hackers can currently use this information to make fake identities, file fraudulent insurance claims, and order and sell expensive drugs and medical equipment. But beyond that, a new kind of cybersecurity threat is around the corner.

Mr. You and others worry that the vast amounts of healthcare data being generated for precision medicine efforts could leave the U.S. vulnerable to cyber and biological attacks. In the wrong hands, this data could be used to exploit or extort an individual, discriminate against certain groups of people, make targeted bioweapons, or give another country an economic advantage.

Precision medicine, of course, is the idea that medical treatments can be tailored to individuals based on their genetics, environment, lifestyle or other traits. But to do that requires collecting and analyzing huge quantities of health data from diverse populations. One research effort, called All of Us, launched by the U.S. National Institutes of Health last year, aims to collect genomic and other healthcare data from one million participants with the goal of advancing personalized medical care.

Other initiatives are underway by academic institutions and healthcare organizations. Electronic medical records, genetic tests, wearable health trackers, mobile apps, and social media are all sources of valuable healthcare data that a bad actor could potentially use to learn more about an individual or group of people.

"When you aggregate all of that data together, that becomes a very powerful profile of who you are," Mr. You says.

A supervisory special agent in the biological countermeasures unit within the FBI's weapons of mass destruction directorate, it's Mr. You's job to imagine worst-case bioterror scenarios and figure out how to prevent and prepare for them.

That used to mean focusing on threats like anthrax, Ebola, and smallpox—pathogens that could be used to intentionally infect people—"basically the dangerous bugs," as he puts it. In recent years, advances in gene editing and synthetic biology have given rise to fears that rogue, or even well-intentioned, scientists could create a virulent virus that's intentionally, or unintentionally, released outside the lab.

"If a foreign source, especially a criminal one, has your biological information, then they might have some particular insights into what your future medical needs might be and exploit that."

While Mr. You is still tracking those threats, he's been traveling around the country talking to scientists, lawyers, software engineers, cyber security professionals, government officials and CEOs about new security threats—those posed by genetic and other biological data.

Emerging threats

Mr. You says one possible situation he can imagine is the potential for nefarious actors to use an individual's sensitive medical information to extort or blackmail that person.

"If a foreign source, especially a criminal one, has your biological information, then they might have some particular insights into what your future medical needs might be and exploit that," he says. For instance, "what happens if you have a singular medical condition and an outside entity says they have a treatment for your condition?" You could get talked into paying a huge sum of money for a treatment that ends up being bogus.

Or what if hackers got a hold of a politician or high-profile CEO's health records? Say that person had a disease-causing genetic mutation that could affect their ability to carry out their job in the future and hackers threatened to expose that information. These scenarios may seem far-fetched, but Mr. You thinks they're becoming increasingly plausible.

On a wider scale, Kavita Berger, a scientist at Gryphon Scientific, a Washington, D.C.-area life sciences consulting firm, worries that data from different populations could be used to discriminate against certain groups of people, like minorities and immigrants.

For instance, the advocacy group Human Rights Watch in 2017 flagged a concerning trend in China's Xinjiang territory, a region with a history of government repression. Police there had purchased 12 DNA sequencers and were collecting and cataloging DNA samples from people to build a national database.

"The concern is that this particular province has a huge population of the Muslim minority in China," Ms. Berger says. "Now they have a really huge database of genetic sequences. You have to ask, why does a police station need 12 next-generation sequencers?"

Also alarming is the potential that large amounts of data from different groups of people could lead to customized bioweapons if that data ends up in the wrong hands.

Eleonore Pauwels, a research fellow on emerging cybertechnologies at United Nations University's Centre for Policy Research, says new insights gained from genomic and other data will give scientists a better understanding of how diseases occur and why certain people are more susceptible to certain diseases.

"As you get more and more knowledge about the genomic picture and how the microbiome and the immune system of different populations function, you could get a much deeper understanding about how you could target different populations for treatment but also how you could eventually target them with different forms of bioagents," Ms. Pauwels says.

Economic competitiveness

Another reason hackers might want to gain access to large genomic and other healthcare datasets is to give their country a leg up economically. Many large cyber-attacks on U.S. healthcare organizations have been tied to Chinese hacking groups.

"This is a biological space race and we just haven't woken up to the fact that we're in this race."

"It's becoming clear that China is increasingly interested in getting access to massive data sets that come from different countries," Ms. Pauwels says.

A year after U.S. President Barack Obama conceived of the Precision Medicine Initiative in 2015—later renamed All of Us—China followed suit, announcing the launch of a 15-year, $9 billion precision health effort aimed at turning China into a global leader in genomics.

Chinese genomics companies, too, are expanding their reach outside of Asia. One company, WuXi NextCODE, which has offices in Shanghai, Reykjavik, and Cambridge, Massachusetts, has built an extensive library of genomes from the U.S., China and Iceland, and is now setting its sights on Ireland.

Another Chinese company, BGI, has partnered with Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and Sinai Health System in Toronto, and also formed a collaboration with the Smithsonian Institute to sequence all species on the planet. BGI has built its own advanced genomic sequencing machines to compete with U.S.-based Illumina.

Mr. You says having access to all this data could lead to major breakthroughs in healthcare, such as new blockbuster drugs. "Whoever has the largest, most diverse dataset is truly going to win the day and come up with something very profitable," he says.

Some direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies with offices in the U.S., like Dante Labs, also use BGI to process customers' DNA.

Experts worry that China could race ahead the U.S. in precision medicine because of Chinese laws governing data sharing. Currently, China prohibits the exportation of genetic data without explicit permission from the government. Mr. You says this creates an asymmetry in data sharing between the U.S. and China.

"This is a biological space race and we just haven't woken up to the fact that we're in this race," he said in January at an American Society for Microbiology conference in Washington, D.C. "We don't have access to their data. There is absolutely no reciprocity."

Protecting your data

While Mr. You has been stressing the importance of data security to anyone who will listen, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which makes scientific and policy recommendations on issues of national importance, has commissioned a study on "safeguarding the bioeconomy."

In the meantime, Ms. Berger says organizations that deal with people's health data should assess their security risks and identify potential vulnerabilities in their systems.

As for what individuals can do to protect themselves, she urges people to think about the different ways they're sharing healthcare data—such as via mobile health apps and wearables.

"Ask yourself, what's the benefit of sharing this? What are the potential consequences of sharing this?" she says.

Mr. You also cautions people to think twice before taking consumer DNA tests. They may seem harmless, he says, but at the end of the day, most people don't know where their genetic information is going. "If your genetic sequence is taken, once it's gone, it's gone. There's nothing you can do about it."

An astronaut peers through a portal in outer space.

What if people could just survive on sunlight like plants?

The admittedly outlandish question occurred to me after reading about how climate change will exacerbate drought, flooding, and worldwide food shortages. Many of these problems could be eliminated if human photosynthesis were possible. Had anyone ever tried it?

Extreme space travel exists at an ethically unique spot that makes human experimentation much more palatable.

I emailed Sidney Pierce, professor emeritus in the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of South Florida, who studies a type of sea slug, Elysia chlorotica, that eats photosynthetic algae, incorporating the algae's key cell structure into itself. It's still a mystery how exactly a slug can operate the part of the cell that converts sunlight into energy, which requires proteins made by genes to function, but the upshot is that the slugs can (and do) live on sunlight in-between feedings.

Pierce says he gets questions about human photosynthesis a couple of times a year, but it almost certainly wouldn't be worth it to try to develop the process in a human. "A high-metabolic rate, large animal like a human could probably not survive on photosynthesis," he wrote to me in an email. "The main reason is a lack of surface area. They would either have to grow leaves or pull a trailer covered with them."

In short: Plants have already exploited the best tricks for subsisting on photosynthesis, and unless we want to look and act like plants, we won't have much success ourselves. Not that it stopped Pierce from trying to develop human photosynthesis technology anyway: "I even tried to sell it to the Navy back in the day," he told me. "Imagine photosynthetic SEALS."

It turns out, however, that while no one is actively trying to create photosynthetic humans, scientists are considering the ways humans might need to change to adapt to future environments, either here on the rapidly changing Earth or on another planet. Rice University biologist Scott Solomon has written an entire book, Future Humans, in which he explores the environmental pressures that are likely to influence human evolution from this point forward. On Earth, Solomon says, infectious disease will remain a major driver of change. As for Mars, the big two are lower gravity and radiation, the latter of which bombards the Martian surface constantly because the planet has no magnetosphere.

Although he considers this example "pretty out there," Solomon says one possible solution to Mars' magnetic assault could leave humans not photosynthetic green, but orange, thanks to pigments called carotenoids that are responsible for the bright hues of pumpkins and carrots.

"Carotenoids protect against radiation," he says. "Usually only plants and microbes can produce carotenoids, but there's at least one kind of insect, a particular type of aphid, that somehow acquired the gene for making carotenoids from a fungus. We don't exactly know how that happened, but now they're orange... I view that as an example of, hey, maybe humans on Mars will evolve new kinds of pigmentation that will protect us from the radiation there."

We could wait for an orange human-producing genetic variation to occur naturally, or with new gene editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, we could just directly give astronauts genetic advantages such as carotenoid-producing skin. This may not be as far-off as it sounds: Extreme space travel exists at an ethically unique spot that makes human experimentation much more palatable. If an astronaut already plans to subject herself to the enormous experiment of traveling to, and maybe living out her days on, a dangerous and faraway planet, do we have any obligation to provide all the protection we can?

Probably the most vocal person trying to figure out what genetic protections might help astronauts is Cornell geneticist Chris Mason. His lab has outlined a 10-phase, 500-year plan for human survival, starting with the comparatively modest goal of establishing which human genes are not amenable to change and should be marked with a "Do not disturb" sign.

To be clear, Mason is not actually modifying human beings. Instead, his lab has studied genes in radiation-resistant bacteria, such as the Deinococcus genus. They've expressed proteins called DSUP from tardigrades, tiny water bears that can survive in space, in human cells. They've looked into p53, a gene that is overexpressed in elephants and seems to protect them from cancer. They also developed a protocol to work on the NASA twin study comparing astronauts Scott Kelly, who spent a year aboard the International Space Station, and his brother Mark, who did not, to find out what effects space tends to have on genes in the first place.

In a talk he gave in December, Mason reported that 8.7 percent of Scott Kelly's genes—mostly those associated with immune function, DNA repair, and bone formation—did not return to normal after the astronaut had been home for six months. "Some of these space genes, we could engineer them, activate them, have them be hyperactive when you go to space," he said in that same talk. "When we think about having the hubris to go to a faraway planet...it seems like an almost impossible idea….but I really like people and I want us to survive for a long time, and this is the first step on the stairwell to survive out of the solar system."

What is the most important ability we could give our future selves through science?

There are others performing studies to figure out what capabilities we might bestow on the future-proof superhuman, but none of them are quite as extreme as photosynthesis (although all of them are useful). At Harvard, geneticist George Church wants to engineer cells to be resistant to viruses, such as the common cold and HIV. At Columbia, synthetic biologist Harris Wang is addressing self-sufficient humans more directly—trying to spur kidney cells to produce amino acids that are normally only available from diet.

But perhaps Future Humans author Scott Solomon has the most radical idea. I asked him a version of the classic What would be your superhero power? question: What does he see as the most important ability we could give our future selves through science?

"The empathy gene," he said. "The ability to put yourself in someone else's shoes and see the world as they see it. I think it would solve a lot of our problems."

A model of a human kidney.

Science's dream of creating perfect custom organs on demand as soon as a patient needs one is still a long way off. But tiny versions are already serving as useful research tools and stepping stones toward full-fledged replacements.

Although organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, they are invaluable tools for research.

The Lowdown

Australian researchers have grown hundreds of mini human kidneys in the past few years. Known as organoids, they function much like their full-grown counterparts, minus a few features due to a lack of blood supply.

Cultivated in a petri dish, these kidneys are still a shadow of their human counterparts. They grow no larger than one-sixth of an inch in diameter; fully developed organs are up to five inches in length. They contain no more than a few dozen nephrons, the kidney's individual blood-filtering unit, whereas a fully-grown kidney has about 1 million nephrons. And the dish variety live for just a few weeks.

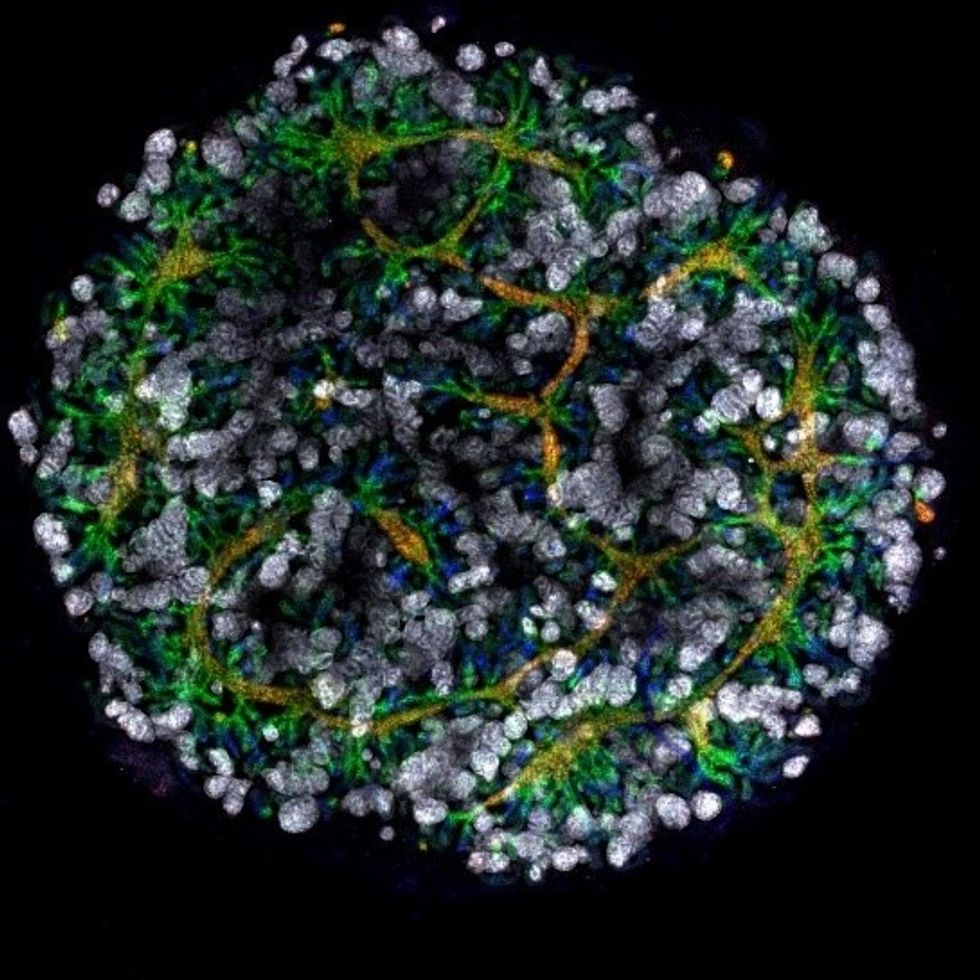

An organoid kidney created by the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo Credit: Shahnaz Khan.

But Melissa Little, head of the kidney research laboratory at the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, says these organoids are invaluable tools for research. Although renal failure is rare in children, more than half of those who suffer from such a disorder inherited it.

The mini kidneys enable scientists to better understand the progression of such disorders because they can be grown with a patient's specific genetic condition.

Mature stem cells can be extracted from a patient's blood sample and then reprogrammed to become like embryonic cells, able to turn into any type of cell in the body. It's akin to walking back the clock so that the cells regain unlimited potential for development. (The Japanese scientist who pioneered this technique was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012.) These "induced pluripotent stem cells" can then be chemically coaxed to grow into mini kidneys that have the patient's genetic disorder.

"The (genetic) defects are quite clear in the organoids, and they can be monitored in the dish," Little says. To date, her research team has created organoids from 20 different stem cell lines.

Medication regimens can also be tested on the organoids, allowing specific tailoring for each patient. For now, such testing remains restricted to mice, but Little says it eventually will be done on human organoids so that the results can more accurately reflect how a given patient will respond to particular drugs.

Next Steps

Although these organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, Little says they may plug a huge gap in renal care by assisting in developing new treatments for chronic conditions. Currently, most patients with a serious kidney disorder see their options narrow to dialysis or organ transplantation. The former not only requires multiple sessions a week, but takes a huge toll on patient health.

Ten percent of older patients on dialysis die every year in the U.S. Aside from the physical trauma of organ transplantation, finding a suitable donor outside of a family member can be difficult.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells."

Meanwhile, the ongoing creation of organoids is supplying Little and her colleagues with enough information to create larger and more functional organs in the future. According to Little, researchers in the Netherlands, for example, have found that implanting organoids in mice leads to the creation of vascular growth, a potential pathway toward creating bigger and better kidneys.

And while Little acknowledges that creating a fully-formed custom organ is the ultimate goal, the mini organs are an important bridge step.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells, and I am just passionate to see it do some good."