Beyond Henrietta Lacks: How the Law Has Denied Every American Ownership Rights to Their Own Cells

A 2017 portrait of Henrietta Lacks.

The common perception is that Henrietta Lacks was a victim of poverty and racism when in 1951 doctors took samples of her cervical cancer without her knowledge or permission and turned them into the world's first immortalized cell line, which they called HeLa. The cell line became a workhorse of biomedical research and facilitated the creation of medical treatments and cures worth untold billions of dollars. Neither Lacks nor her family ever received a penny of those riches.

But racism and poverty is not to blame for Lacks' exploitation—the reality is even worse. In fact all patients, then and now, regardless of social or economic status, have absolutely no right to cells that are taken from their bodies. Some have called this biological slavery.

How We Got Here

The case that established this legal precedent is Moore v. Regents of the University of California.

John Moore was diagnosed with hairy-cell leukemia in 1976 and his spleen was removed as part of standard treatment at the UCLA Medical Center. On initial examination his physician, David W. Golde, had discovered some unusual qualities to Moore's cells and made plans prior to the surgery to have the tissue saved for research rather than discarded as waste. That research began almost immediately.

"On both sides of the case, legal experts and cultural observers cautioned that ownership of a human body was the first step on the slippery slope to 'bioslavery.'"

Even after Moore moved to Seattle, Golde kept bringing him back to Los Angeles to collect additional samples of blood and tissue, saying it was part of his treatment. When Moore asked if the work could be done in Seattle, he was told no. Golde's charade even went so far as claiming to find a low-income subsidy to pay for Moore's flights and put him up in a ritzy hotel to get him to return to Los Angeles, while paying for those out of his own pocket.

Moore became suspicious when he was asked to sign new consent forms giving up all rights to his biological samples and he hired an attorney to look into the matter. It turned out that Golde had been lying to his patient all along; he had been collecting samples unnecessary to Moore's treatment and had turned them into a cell line that he and UCLA had patented and already collected millions of dollars in compensation. The market for the cell lines was estimated at $3 billion by 1990.

Moore felt he had been taken advantage of and filed suit to claim a share of the money that had been made off of his body. "On both sides of the case, legal experts and cultural observers cautioned that ownership of a human body was the first step on the slippery slope to 'bioslavery,'" wrote Priscilla Wald, a professor at Duke University whose career has focused on issues of medicine and culture. "Moore could be viewed as asking to commodify his own body part or be seen as the victim of the theft of his most private and inalienable information."

The case bounced around different levels of the court system with conflicting verdicts for nearly six years until the California Supreme Court ruled on July 9, 1990 that Moore had no legal rights to cells and tissue once they were removed from his body.

The court made a utilitarian argument that the cells had no value until scientists manipulated them in the lab. And it would be too burdensome for researchers to track individual donations and subsequent cell lines to assure that they had been ethically gathered and used. It would impinge on the free sharing of materials between scientists, slow research, and harm the public good that arose from such research.

"In effect, what Moore is asking us to do is impose a tort duty on scientists to investigate the consensual pedigree of each human cell sample used in research," the majority wrote. In other words, researchers don't need to ask any questions about the materials they are using.

One member of the court did not see it that way. In his dissent, Stanley Mosk raised the specter of slavery that "arises wherever scientists or industrialists claim, as defendants have here, the right to appropriate and exploit a patient's tissue for their sole economic benefit—the right, in other words, to freely mine or harvest valuable physical properties of the patient's body. … This is particularly true when, as here, the parties are not in equal bargaining positions."

Mosk also cited the appeals court decision that the majority overturned: "If this science has become for profit, then we fail to see any justification for excluding the patient from participation in those profits."

But the majority bought the arguments that Golde, UCLA, and the nascent biotechnology industry in California had made in amici briefs filed throughout the legal proceedings. The road was now cleared for them to develop products worth billions without having to worry about or share with the persons who provided the raw materials upon which their research was based.

Critical Views

Biomedical research requires a continuous and ever-growing supply of human materials for the foundation of its ongoing work. If an increasing number of patients come to feel as John Moore did, that the system is ripping them off, then they become much less likely to consent to use of their materials in future research.

Some legal and ethical scholars say that donors should be able to limit the types of research allowed for their tissues and researchers should be monitored to assure compliance with those agreements. For example, today it is commonplace for companies to certify that their clothing is not made by child labor, their coffee is grown under fair trade conditions, that food labeled kosher is properly handled. Should we ask any less of our pharmaceuticals than that the donors whose cells made such products possible have been treated honestly and fairly, and share in the financial bounty that comes from such drugs?

Protection of individual rights is a hallmark of the American legal system, says Lisa Ikemoto, a law professor at the University of California Davis. "Putting the needs of a generalized public over the interests of a few often rests on devaluation of the humanity of the few," she writes in a reimagined version of the Moore decision that upholds Moore's property claims to his excised cells. The commentary is in a chapter of a forthcoming book in the Feminist Judgment series, where authors may only use legal precedent in effect at the time of the original decision.

"Why is the law willing to confer property rights upon some while denying the same rights to others?" asks Radhika Rao, a professor at the University of California, Hastings College of the Law. "The researchers who invest intellectual capital and the companies and universities that invest financial capital are permitted to reap profits from human research, so why not those who provide the human capital in the form of their own bodies?" It might be seen as a kind of sweat equity where cash strapped patients make a valuable in kind contribution to the enterprise.

The Moore court also made a big deal about inhibiting the free exchange of samples between scientists. That has become much less the situation over the more than three decades since the decision was handed down. Ironically, this decision, as well as other laws and regulations, have since strengthened the power of patents in biomedicine and by doing so have increased secrecy and limited sharing.

"Although the research community theoretically endorses the sharing of research, in reality sharing is commonly compromised by the aggressive pursuit and defense of patents and by the use of licensing fees that hinder collaboration and development," Robert D. Truog, Harvard Medical School ethicist and colleagues wrote in 2012 in the journal Science. "We believe that measures are required to ensure that patients not bear all of the altruistic burden of promoting medical research."

Additionally, the increased complexity of research and the need for exacting standardization of materials has given rise to an industry that supplies certified chemical reagents, cell lines, and whole animals bred to have specific genetic traits to meet research needs. This has been more efficient for research and has helped to ensure that results from one lab can be reproduced in another.

The Court's rationale of fostering collaboration and free exchange of materials between researchers also has been undercut by the changing structure of that research. Big pharma has shrunk the size of its own research labs and over the last decade has worked out cooperative agreements with major research universities where the companies contribute to the research budget and in return have first dibs on any findings (and sometimes a share of patent rights) that come out of those university labs. It has had a chilling effect on the exchange of materials between universities.

Perhaps tracking cell line donors and use restrictions on those donations might have been burdensome to researchers when Moore was being litigated. Some labs probably still kept their cell line records on 3x5 index cards, computers were primarily expensive room-size behemoths with limited capacity, the internet barely existed, and there was no cloud storage.

But that was the dawn of a new technological age and standards have changed. Now cell lines are kept in state-of-the-art sub zero storage units, tagged with the source, type of tissue, date gathered and often other information. Adding a few more data fields and contacting the donor if and when appropriate does not seem likely to disrupt the research process, as the court asserted.

Forging the Future

"U.S. universities are awarded almost 3,000 patents each year. They earn more than $2 billion each year from patent royalties. Sharing a modest portion of these profits is a novel method for creating a greater sense of fairness in research relationships that we think is worth exploring," wrote Mark Yarborough, a bioethicist at the University of California Davis Medical School, and colleagues. That was penned nearly a decade ago and those numbers have only grown.

The Michigan BioTrust for Health might serve as a useful model in tackling some of these issues. Dried blood spots have been collected from all newborns for half a century to be tested for certain genetic diseases, but controversy arose when the huge archive of dried spots was used for other research projects. As a result, the state created a nonprofit organization to in essence become a biobank and manage access to these spots only for specific purposes, and also to share any revenue that might arise from that research.

"If there can be no property in a whole living person, does it stand to reason that there can be no property in any part of a living person? If there were, can it be said that this could equate to some sort of 'biological slavery'?" Irish ethicist Asim A. Sheikh wrote several years ago. "Any amount of effort spent pondering the issue of 'ownership' in human biological materials with existing law leaves more questions than answers."

Perhaps the biggest question will arise when -- not if but when -- it becomes possible to clone a human being. Would a human clone be a legal person or the property of those who created it? Current legal precedent points to it being the latter.

Today, October 4, is the 70th anniversary of Henrietta Lacks' death from cancer. Over those decades her immortalized cells have helped make possible miraculous advances in medicine and have had a role in generating billions of dollars in profits. Surviving family members have spoken many times about seeking a share of those profits in the name of social justice; they intend to file lawsuits today. Such cases will succeed or fail on their own merits. But regardless of their specific outcomes, one can hope that they spark a larger public discussion of the role of patients in the biomedical research enterprise and lead to establishing a legal and financial claim for their contributions toward the next generation of biomedical research.

Out of Thin Air: A Fresh Solution to Farming’s Water Shortages

Dry, arid and remote farming regions are vulnerable to water shortages, but scientists are working on a promising new solution.

California has been plagued by perilous droughts for decades. Freshwater shortages have sparked raging wildfires and killed fruit and vegetable crops. And California is not alone in its danger of running out of water for farming; parts of the Southwest, including Texas, are battling severe drought conditions, according to the North American Drought Monitor. These two states account for 316,900 of the 2 million total U.S. farms.

But even as farming becomes more vulnerable due to water shortages, the world's demand for food is projected to increase 70 percent by 2050, according to Guihua Yu, an associate professor of materials science at The University of Texas at Austin.

"Water is the most limiting natural resource for agricultural production because of the freshwater shortage and enormous water consumption needed for irrigation," Yu said.

As scientists have searched for solutions, an alternative water supply has been hiding in plain sight: Water vapor in the atmosphere. It is abundant, available, and endlessly renewable, just waiting for the moment that technological innovation and necessity converged to make it fit for use. Now, new super-moisture-absorbent gels developed by Yu and a team of researchers can pull that moisture from the air and bring it into soil, potentially expanding the map of farmable land around the globe to dry and remote regions that suffer from water shortages.

"This opens up opportunities to turn those previously poor-quality or inhospitable lands to become useable and without need of centralized water and power supplies," Yu said.

A renewable source of freshwater

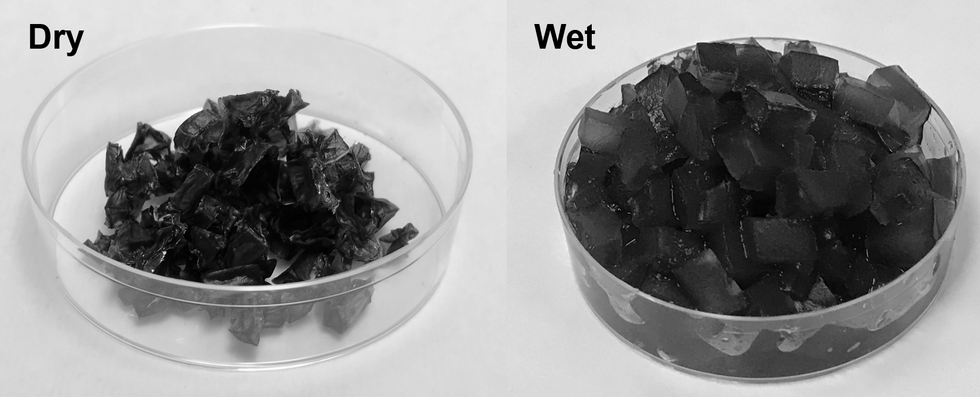

The hydrogels are a gelatin-like substance made from synthetic materials. The gels activate in cooler, humid overnight periods and draw water from the air. During a four-week experiment, Yu's team observed that soil with these gels provided enough water to support seed germination and plant growth without an additional liquid water supply. And the soil was able to maintain the moist environment for more than a month, according to Yu.

The super absorbent gels developed at the University of Texas at Austin.

Xingyi Zhou, UT Austin

"It is promising to liberate underdeveloped and drought areas from the long-distance water and power supplies for agricultural production," Yu said.

Crops also rely on fertilizer to maintain soil fertility and increase the production yield, but it is easily lost through leaching. Runoff increases agricultural costs and contributes to environmental pollution. The interaction between the gels and agrochemicals offer slow and controlled fertilizer release to maintain the balance between the root of the plant and the soil.

The possibilities are endless

Harvesting atmospheric water is exciting on multiple fronts. The super-moisture-absorbent gel can also be used for passively cooling solar panels. Solar radiation is the magic behind the process. Overnight, as temperatures cool, the gels absorb water hanging in the atmosphere. The moisture is stored inside the gels until the thermometer rises. Heat from the sun serves as the faucet that turns the gels on so they can release the stored water and cool down the panels. Effective cooling of the solar panels is important for sustainable long-term power generation.

In addition to agricultural uses and cooling for energy devices, atmospheric water harvesting technologies could even reach people's homes.

"They could be developed to enable easy access to drinking water through individual systems for household usage," Yu said.

Next steps

Yu and the team are now focused on affordability and developing practical applications for use. The goal is to optimize the gel materials to achieve higher levels of water uptake from the atmosphere.

"We are exploring different kinds of polymers and solar absorbers while exploring low-cost raw materials for production," Yu said.

The ability to transform atmospheric water vapor into a cheap and plentiful water source would be a game-changer. One day in the not-too-distant future, if climate change intensifies and droughts worsen, this innovation may become vital to our very survival.

On left, people excitedly line up for Salk's polio vaccine in 1957; on right, Joe Biden gets one of the COVID vaccines on December 21, 2020.

On the morning of April 12, 1955, newsrooms across the United States inked headlines onto newsprint: the Salk Polio vaccine was "safe, effective, and potent." This was long-awaited news. Americans had limped through decades of fear, unaware of what caused polio or how to cure it, faced with the disease's terrifying, visible power to paralyze and kill, particularly children.

The announcement of the polio vaccine was celebrated with noisy jubilation: church bells rang, factory whistles sounded, people wept in the streets. Within weeks, mass inoculation began as the nation put its faith in a vaccine that would end polio.

Today, most of us are blissfully ignorant of child polio deaths, making it easier to believe that we have not personally benefited from the development of vaccines. According to Dr. Steven Pinker, cognitive psychologist and author of the bestselling book Enlightenment Now, we've become blasé to the gifts of science. "The default expectation is not that disease is part of life and science is a godsend, but that health is the default, and any disease is some outrage," he says.

We're now in the early stages of another vaccine rollout, one we hope will end the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. And yet, the Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines are met with far greater hesitancy and skepticism than the polio vaccine was in the 50s.

In 2021, concerns over the speed and safety of vaccine development and technology plague this heroic global effort, but the roots of vaccine hesitancy run far deeper. Vaccine hesitancy has always existed in the U.S., even in the polio era, motivated in part by fears around "living virus" in a bad batch of vaccines produced by Cutter Laboratories in 1955. But in the last half century, we've witnessed seismic cultural shifts—loss of public trust, a rise in misinformation, heightened racial and socioeconomic inequality, and political polarization have all intensified vaccine-related fears and resistance. Making sense of how we got here may help us understand how to move forward.

The Rise and Fall of Public Trust

When the polio vaccine was released in 1955, "we were nearing an all-time high point in public trust," says Matt Baum, Harvard Kennedy School professor and lead author of several reports measuring public trust and vaccine confidence. Baum explains that the U.S. was experiencing a post-war boom following the Allied triumph in WWII, a popular Roosevelt presidency, and the rapid innovation that elevated the country to an international superpower.

The 1950s witnessed the emergence of nuclear technology, a space program, and unprecedented medical breakthroughs, adds Emily Brunson, Texas State University anthropologist and co-chair of the Working Group on Readying Populations for COVID-19 Vaccine. "Antibiotics were a game changer," she states. While before, people got sick with pneumonia for a month, suddenly they had access to pills that accelerated recovery.

During this period, science seemed to hold all the answers; people embraced the idea that we could "come to know the world with an absolute truth," Brunson explains. Doctors were portrayed as unquestioned gods, so Americans were primed to trust experts who told them the polio vaccine was safe.

"The emotional tone of the news has gone downward since the 1940s, and journalists consider it a professional responsibility to cover the negative."

That blind acceptance eroded in the 1960s and 70s as people came to understand that science can be inherently political. "Getting to an absolute truth works out great for white men, but these things affect people socially in radically different ways," Brunson says. As the culture began questioning the white, patriarchal biases of science, doctors lost their god-like status and experts were pushed off their pedestals. This trend continues with greater intensity today, as President Trump has led a campaign against experts and waged a war on science that began long before the pandemic.

The Shift in How We Consume Information

In the 1950s, the media created an informational consensus. The fundamental ideas the public consumed about the state of the world were unified. "People argued about the best solutions, but didn't fundamentally disagree on the factual baseline," says Baum. Indeed, the messaging around the polio vaccine was centralized and consistent, led by President Roosevelt's successful March of Dimes crusade. People of lower socioeconomic status with limited access to this information were less likely to have confidence in the vaccine, but most people consumed media that assured them of the vaccine's safety and mobilized them to receive it.

Today, the information we consume is no longer centralized—in fact, just the opposite. "When you take that away, it's hard for people to know what to trust and what not to trust," Baum explains. We've witnessed an increase in polarization and the technology that makes it easier to give people what they want to hear, reinforcing the human tendencies to vilify the other side and reinforce our preexisting ideas. When information is engineered to further an agenda, each choice and risk calculation made while navigating the COVID-19 pandemic is deeply politicized.

This polarization maps onto a rise in socioeconomic inequality and economic uncertainty. These factors, associated with a sense of lost control, prime people to embrace misinformation, explains Baum, especially when the situation is difficult to comprehend. "The beauty of conspiratorial thinking is that it provides answers to all these questions," he says. Today's insidious fragmentation of news media accelerates the circulation of mis- and disinformation, reaching more people faster, regardless of veracity or motivation. In the case of vaccines, skepticism around their origin, safety, and motivation is intensified.

Alongside the rise in polarization, Pinker says "the emotional tone of the news has gone downward since the 1940s, and journalists consider it a professional responsibility to cover the negative." Relentless focus on everything that goes wrong further erodes public trust and paints a picture of the world getting worse. "Life saved is not a news story," says Pinker, but perhaps it should be, he continues. "If people were more aware of how much better life was generally, they might be more receptive to improvements that will continue to make life better. These improvements don't happen by themselves."

The Future Depends on Vaccine Confidence

So far, the U.S. has been unable to mitigate the catastrophic effects of the pandemic through social distancing, testing, and contact tracing. President Trump has downplayed the effects and threat of the virus, censored experts and scientists, given up on containing the spread, and mobilized his base to protest masks. The Trump Administration failed to devise a national plan, so our national plan has defaulted to hoping for the "miracle" of a vaccine. And they are "something of a miracle," Pinker says, describing vaccines as "the most benevolent invention in the history of our species." In record-breaking time, three vaccines have arrived. But their impact will be weakened unless we achieve mass vaccination. As Brunson notes, "The technology isn't the fix; it's people taking the technology."

Significant challenges remain, including facilitating widespread access and supporting on-the-ground efforts to allay concerns and build trust with specific populations with historic reasons for distrust, says Brunson. Baum predicts continuing delays as well as deaths from other causes that will be linked to the vaccine.

Still, there's every reason for hope. The new administration "has its eyes wide open to these challenges. These are the kind of problems that are amenable to policy solutions if we have the will," Baum says. He forecasts widespread vaccination by late summer and a bounce back from the economic damage, a "Good News Story" that will bolster vaccine acceptance in the future. And Pinker reminds us that science, medicine, and public health have greatly extended our lives in the last few decades, a trend that can only continue if we're willing to roll up our sleeves.