Biden’s Administration Should Immediately Prioritize These Five Pandemic Tasks

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA

Democratic U.S. presidential nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden puts his face mask back on after answering questions following a speech on the effects on the U.S. economy of the Trump administration's response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic during a campaign event in Wilmington, Delaware, U.S., September 4, 2020.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic will soon become the responsibility of President-elect Biden. As is clear to anyone who honestly looks, the past 10+ months of this pandemic have been a disastrous litany of mistakes, wrong actions, and misinformation.

The result has been the deaths of 240,000 Americans, economic collapse, disruption of routine healthcare, and inability of Americans to pursue their values without fear of contracting or spreading a deadly infectious disease. With the looming change in administration, many proposals will be suggested for the path forward.

Indeed, the Biden campaign published their own plan. This plan encompasses many of the actions my colleagues and I in the public health and infectious disease fields have been arguing for since January. Several of these points, I think, bear emphasis and should be aggressively pursued to help the U.S. emerge from the pandemic.

Support More and Faster Tests

When it comes to an infectious disease outbreak the most basic question that must be answered in any response is: "Who is infected and who is not?" Even today this simple question is not easy to answer because testing issues continue to plague us and there are voices who oppose more testing -- as if by not testing, the cases of COVID cease to exist. While testing is worlds better than it was in March – especially for hospital inpatients – it is still a process fraught with unnecessary bureaucracy and delays in the outpatient setting.

Just this past week, friends and colleagues have had to wait days upon days to get a result back, all the while having to self-quarantine pending the result. This not only leaves people in limbo, it discourages people from being tested, and renders contact tracing almost moot. A test that results in several days is almost useless to contact tracers as Bill Gates has forcefully argued.

We need more testing and more actionable rapid turn-around tests. These tests need to be deployed in healthcare facilities and beyond. Ideally, these tests should be made available for individuals to conduct on themselves at home. For some settings, such as at home, rapid antigen tests similar to those used to detect pregnancy will be suitable; for other settings, like at a doctor's office or a hospital, more elaborate PCR tests will still be key. These last have been compromised for several months due to rationing of the reagent supplies necessary to perform the test – an unacceptable state of affairs that cannot continue. Reflecting an understanding of the state of play of testing, the President-elect recently stated: "We need to increase both lab-based diagnostic testing, with results back within 24 hours or less, and faster, cheaper screening tests that you can take right at home or in school."

Roll Out Safe and Effective Vaccine(s)

Biden's plan also identifies the need to "accelerate the development of treatments and vaccines" and indeed Operation Warp Speed has been one solitary bright spot in the darkness of the failed pandemic response. It is this program that facilitated a distribution partnership with Pfizer for 100 million doses of its mRNA vaccine -- whose preliminary, and extremely positive data, was just announced today to great excitement.

Operation Warp Speed needs to be continued so that we can ensure the final development and distribution of the first-generation vaccines and treatments. When a vaccine is available, it will be a Herculean task that will span many months to actually get into the arms (twice as a 2-dose vaccine) of Americans. Vaccination may begin for healthcare workers before a change in administration, but it will continue long into 2021 and possibly longer. Vaccine distribution will be a task that demands a high degree of competence and coordination, especially with the extreme cold storage conditions needed for the vaccines.

Anticipate the Next Pandemic Now

Not only should Operation Warp Speed be supported, it needs to be expanded. For too long pandemic preparedness has been reactive and it is long past time to approach the development of medical countermeasures for pandemic threats in a proactive fashion.

What we do for other national security threats should be the paradigm for infectious disease threats that too often are subject to a mind-boggling cycle of panic and neglect. There are an estimated 200 outbreaks of viral diseases per year. Luckily and because of hard work, for many of them we have tools at our hands to control them, but for the unknown 201st virus outbreak we do not –as we've seen this year. And, the next unknown virus will likely appear soon. A new program must be constructed guaranteeing that we will never again be caught blindsided and flatfooted as we have been with the COVID-19 pandemic.

A new dedicated "Virus 201" strategy, program, and funding must be created to achieve this goal. This initiative should be a specific program focused on unknown threats that emanate from identified classes of pathogens that possess certain pandemic-causing characteristics. For example, such a program could leverage new powerful vaccine platform technologies to begin development on vaccine candidates for a variety of viral families before they emerge as full-fledged threats. Imagine how different our world would be today if this action was taken after SARS in 2003 or even MERS in 2012.

Biden should remove the handcuffs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and allow its experts to coordinate the national response and to issue guidance in the manner they were constituted to do without fear of political reprisal.

Resurrect Expertise

One of the most disheartening aspects of the pandemic has been the denigration and outright attacks on experts in infectious disease. Such disgusting attacks were not for any flaws, incompetence, or weakness but for their opposite -- strength and competence – and emanated from a desire to evade the grim reality. Such nihilism must end and indeed the Biden plan contains several crucial remedies, including the restoration of the White House National Security Council Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense, a crucial body of experts at the White House that the Trump administration bafflingly eliminated in 2018.

Additionally, Biden should remove the handcuffs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and allow its experts to coordinate the national response and to issue guidance in the manner they were constituted to do without fear of political reprisal.

Shore Up Hospital Capacity

For the foreseeable future, as control of the virus slips away in certain parts of the country, hospital capacity will be the paramount concern. Unlike many other industries, the healthcare sector is severely constrained in its ability to expand capacity because of regulatory and financial considerations. Hospital emergency preparedness has never been prioritized and until we can substantially curtail the spread of this virus, hospitals must remain vigilant.

We have seen how suspensions of "elective" procedures led to alarming declines in vital healthcare services that range from childhood immunization to cancer chemotherapy to psychiatric care. This cannot be allowed to happen again. Hospitals will need support in terms of staffing, alternative care sites, and personal protective equipment. Reflecting these concerns, the Biden plan outlines an approach that smartly uses the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs assets and medical reserve corps, coupled to the now-flourishing telemedicine innovations, to augment capacity and forestall the need for hospitals to shift to crisis standards of care.

To these five tasks, I would add a long list of subtasks that need to be executed by agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, the Food and Drug Administration, and many other arms of government. But, to me, these are the most crucial.

***

As COVID-19 has demonstrated, new deadly viruses can spread quickly and easily around the globe, causing significant loss of life and economic ruin. With nearly 200 epidemics occurring each year, the next fast-moving, novel infectious disease pandemic could be right around the corner.

The upcoming transition affords the opportunity to implement a new paradigm in pandemic response, biosecurity, and emerging disease response. The United States and President-elect Biden must work hard to to end this pandemic and increase the resilience of the United States to the future infectious disease threats we will surely face.

Dr. Adalja is focused on emerging infectious disease, pandemic preparedness, and biosecurity. He has served on US government panels tasked with developing guidelines for the treatment of plague, botulism, and anthrax in mass casualty settings and the system of care for infectious disease emergencies, and as an external advisor to the New York City Health and Hospital Emergency Management Highly Infectious Disease training program, as well as on a FEMA working group on nuclear disaster recovery. Dr. Adalja is an Associate Editor of the journal Health Security. He was a coeditor of the volume Global Catastrophic Biological Risks, a contributing author for the Handbook of Bioterrorism and Disaster Medicine, the Emergency Medicine CorePendium, Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple, UpToDate's section on biological terrorism, and a NATO volume on bioterrorism. He has also published in such journals as the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Emerging Infectious Diseases, and the Annals of Emergency Medicine. He is a board-certified physician in internal medicine, emergency medicine, infectious diseases, and critical care medicine. Follow him on Twitter: @AmeshAA

In this week's Friday Five, an old diabetes drug finds an exciting new purpose. Plus, how to make the cities of the future less toxic, making old mice younger with EVs, a new reason for mysterious stillbirths - and much more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here is the promising research covered in this week's Friday Five:

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- How to make cities of the future less noisy

- An old diabetes drug could have a new purpose: treating an irregular heartbeat

- A new reason for mysterious stillbirths

- Making old mice younger with EVs

- No pain - or mucus - no gain

And an honorable mention this week: How treatments for depression can change the structure of the brain

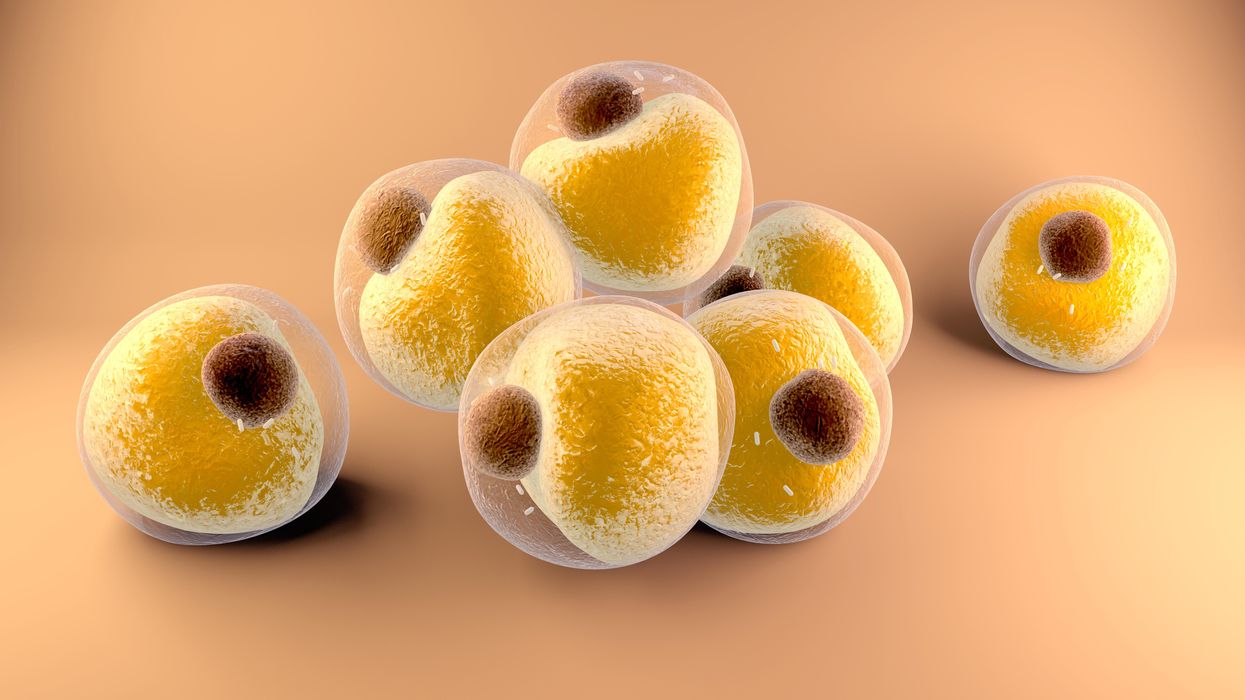

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.