Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Although Jonas Salk has gone down in history for helping rid the world (almost) of polio, his revolutionary vaccine wouldn't have been possible without the world’s largest clinical trial – and the bravery of thousands of kids.

Exactly 67 years ago, in 1955, a group of scientists and reporters gathered at the University of Michigan and waited with bated breath for Dr. Thomas Francis Jr., director of the school’s Poliomyelitis Vaccine Evaluation Center, to approach the podium. The group had gathered to hear the news that seemingly everyone in the country had been anticipating for the past two years – whether the vaccine for poliomyelitis, developed by Francis’s former student Jonas Salk, was effective in preventing the disease.

Polio, at that point, had become a household name. As the highly contagious virus swept through the United States, cities closed their schools, movie theaters, swimming pools, and even churches to stop the spread. For most, polio presented as a mild illness, and was usually completely asymptomatic – but for an unlucky few, the virus took hold of the central nervous system and caused permanent paralysis of muscles in the legs, arms, and even people’s diaphragms, rendering the person unable to walk and breathe. It wasn’t uncommon to hear reports of people – mostly children – who fell sick with a flu-like virus and then, just days later, were relegated to spend the rest of their lives in an iron lung.

For two years, researchers had been testing a vaccine that would hopefully be able to stop the spread of the virus and prevent the 45,000 infections each year that were keeping the nation in a chokehold. At the podium, Francis greeted the crowd and then proceeded to change the course of human history: The vaccine, he reported, was “safe, effective, and potent.” Widespread vaccination could begin in just a few weeks. The nightmare was over.

The road to success

Jonas Salk, a medical researcher and virologist who developed the vaccine with his own research team, would rightfully go down in history as the man who eradicated polio. (Today, wild poliovirus circulates in just two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan – with only 140 cases reported in 2020.) But many people today forget that the widespread vaccination campaign that effectively ended wild polio across the globe would have never been possible without the human clinical trials that preceded it.

As with the COVID-19 vaccine, skepticism and misinformation around the polio vaccine abounded. But even more pervasive than the skepticism was fear. The consequences of polio had arguably never been more visible.

The road to human clinical trials – and the resulting vaccine – was a long one. In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt launched the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in order to raise funding for research and development of a polio vaccine. (Today, we know this organization as the March of Dimes.) A polio survivor himself, Roosevelt elevated awareness and prevention into the national spotlight, even more so than it had been previously. Raising funds for a safe and effective polio vaccine became a cornerstone of his presidency – and the funds raked in by his foundation went primarily to Salk to fund his research.

The Trials Begin

Salk’s vaccine, which included an inactivated (killed) polio virus, was promising – but now the researchers needed test subjects to make global vaccination a possibility. Because the aim of the vaccine was to prevent paralytic polio, researchers decided that they had to test the vaccine in the population that was most vulnerable to paralysis – young children. And, because the rate of paralysis was so low even among children, the team required many children to collect enough data. Francis, who led the trial to evaluate Salk’s vaccine, began the process of recruiting more than one million school-aged children between the ages of six and nine in 272 counties that had the highest incidence of the disease. The participants were nicknamed the “Polio Pioneers.”

Double-blind, placebo-based trials were considered the “gold standard” of epidemiological research back in Francis's day - and they remain the best approach we have today. These rigorous scientific studies are designed with two participant groups in mind. One group, called the test group, receives the experimental treatment (such as a vaccine); the other group, called the control, receives an inactive treatment known as a placebo. The researchers then compare the effects of the active treatment against the effects of the placebo, and every researcher is “blinded” as to which participants receive what treatment. That way, the results aren’t tainted by any possible biases.

But the study was controversial in that only some of the individual field trials at the county and state levels had a placebo group. Researchers described this as a “calculated risk,” meaning that while there were risks involved in giving the vaccine to a large number of children, the bigger risk was the potential paralysis or death that could come with being infected by polio. In all, just 200,000 children across the US received a placebo treatment, while an additional 725,000 children acted as observational controls – in other words, researchers monitored them for signs of infection, but did not give them any treatment.

As with the COVID-19 vaccine, skepticism and misinformation around the polio vaccine abounded. But even more pervasive than the skepticism was fear. President Roosevelt, who had made many public and televised appearances in a wheelchair, served as a perpetual reminder of the consequences of polio, as an infection at age 39 had rendered him permanently unable to walk. The consequences of polio had arguably never been more visible, and parents signed up their children in droves to participate in the study and offer them protection.

The Polio Pioneer Legacy

In a little less than a year, roughly half a million children received a dose of Salk’s polio vaccine. While plenty of children were hesitant to get the shot, many former participants still remember the fear surrounding the disease. One former participant, a Polio Pioneer named Debbie LaCrosse, writes of her experience: “There was no discussion, no listing of pros and cons. No amount of concern over possible side effects or other unknowns associated with a new vaccine could compare to the terrifying threat of polio.” For their participation, each kid received a certificate – and sometimes a pin – with the words “Polio Pioneer” emblazoned across the front.

When Francis announced the results of the trial on April 12, 1955, people did more than just breathe a sigh of relief – they openly celebrated, ringing church bells and flooding into the streets to embrace. Salk, who had become the face of the vaccine at that point, was instantly hailed as a national hero – and teachers around the country had their students to write him ‘thank you’ notes for his years of diligent work.

But while Salk went on to win national acclaim – even accepting the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work on the polio vaccine in 1977 – his success was due in no small part to the children (and their parents) who took a risk in order to advance medical science. And that risk paid off: By the early 1960s, the yearly cases of polio in the United States had gone down to just 910. Where before the vaccine polio had caused around 15,000 cases of paralysis each year, only ten cases of paralysis were recorded in the entire country throughout the 1970s. And in 1979, the virus that once shuttered entire towns was declared officially eradicated in this country. Thanks to the efforts of these brave pioneers, the nation – along with the majority of the world – remains free of polio even today.

Why you should (virtually) care

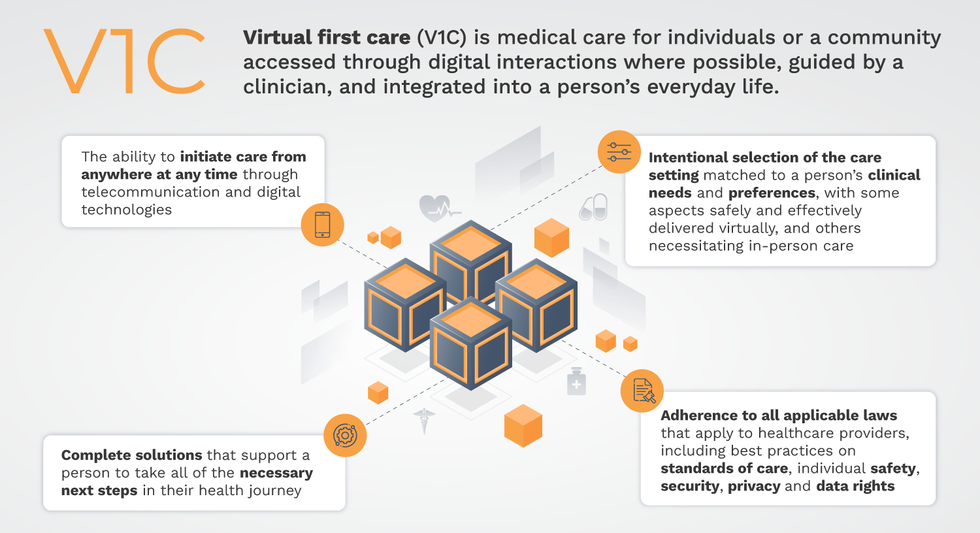

Virtual-first care, or V1C, could increase the quality of healthcare and make it more patient-centric by letting patients combine in-person visits with virtual options such as video for seeing their care providers.

As the pandemic turns endemic, healthcare providers have been eagerly urging patients to return to their offices to enjoy the benefits of in-person care.

But wait.

The last two years have forced all sorts of organizations to be nimble, adaptable and creative in how they work, and this includes healthcare providers’ efforts to maintain continuity of care under the most challenging of conditions. So before we go back to “business as usual,” don’t we owe it to those providers and ourselves to admit that business as usual did not work for most of the people the industry exists to help? If we’re going to embrace yet another period of change – periods that don’t happen often in our complex industry – shouldn’t we first stop and ask ourselves what we’re trying to achieve?

Certainly, COVID has shown that telehealth can be an invaluable tool, particularly for patients in rural and underserved communities that lack access to specialty care. It’s also become clear that many – though not all – healthcare encounters can be effectively conducted from afar. That said, the telehealth tactics that filled the gap during the pandemic were largely stitched together substitutes for existing visit-based workflows: with offices closed, patients scheduled video visits for help managing the side effects of their blood pressure medications or to see their endocrinologist for a quarterly check-in. Anyone whose children slogged through the last year or two of remote learning can tell you that simply virtualizing existing processes doesn’t necessarily improve the experience or the outcomes!

But what if our approach to post-pandemic healthcare came from a patient-driven perspective? We have a fleeting opportunity to advance a care model centered on convenient and equitable access that first prioritizes good outcomes, then selects approaches to care – and locations – tailored to each patient. Using the example of education, imagine how effective it would be if each student, regardless of their school district and aptitude, received such individualized attention.

That’s the idea behind virtual-first care (V1C), a new care model centered on convenient, customized, high-quality care that integrates a full suite of services tailored directly to patients’ clinical needs and preferences. This package includes asynchronous communication such as texting; video and other live virtual modes; and in-person options.

V1C goes beyond what you might think of as standard “telehealth” by using evidence-based protocols and tools that include traditional and digital therapeutics and testing, personalized care plans, dynamic patient monitoring, and team-based approaches to care. This could include spit kits mailed for laboratory tests and complementing clinical care with health coaching. V1C also replaces some in-person exams with ongoing monitoring, using sensors for more ‘whole person’ care.

Amidst all this momentum, we have the opportunity to rethink the goals of healthcare innovation, but that means bringing together key stakeholders to demonstrate that sustainable V1C can redefine healthcare.

Established V1C healthcare providers such as Omada, Headspace, and Heartbeat Health, as well as emerging market entrants like Oshi, Visana, and Wellinks, work with a variety of patients who have complicated long-term conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, gastrointestinal illness, endometriosis, and COPD. V1C is comprehensive in ways that are lacking in digital health and its other predecessors: it has the potential to integrate multiple data streams, incorporate more frequent touches and check-ins over time, and manage a much wider range of chronic health conditions, improving lives and reducing disease burden now and in the future.

Recognizing the pandemic-driven interest in virtual care, significant energy and resources are already flowing fast toward V1C. Some of the world’s largest innovators jumped into V1C early on: Verily, Alphabet’s Life Sciences Company, launched Onduo in 2016 to disrupt the diabetes healthcare market, and is now well positioned to scale its solutions. Major insurers like Aetna and United now offer virtual-first plans to members, responding as organizations expand virtual options for employees. Amidst all this momentum, we have the opportunity to rethink the goals of healthcare innovation, but that means bringing together key stakeholders to demonstrate that sustainable V1C can redefine healthcare.

That was the immediate impetus for IMPACT, a consortium of V1C companies, investors, payers and patients founded last year to ensure access to high-quality, evidence-based V1C. Developed by our team at the Digital Medicine Society (DiMe) in collaboration with the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), IMPACT has begun to explore key issues that include giving patients more integrated experiences when accessing both virtual and brick-and-mortar care.

Digital Medicine Society

V1C is not, nor should it be, virtual-only care. In this new era of hybrid healthcare, success will be defined by how well providers help patients navigate the transitions. How do we smoothly hand a patient off from an onsite primary care physician to, say, a virtual cardiologist? How do we get information from a brick-and-mortar to a digital portal? How do you manage dataflow while still staying HIPAA compliant? There are many complex regulatory implications for these new models, as well as an evolving landscape in terms of privacy, security and interoperability. It will be no small task for groups like IMPACT to determine the best path forward.

None of these factors matter unless the industry can recruit and retain clinicians. Our field is facing an unprecedented workforce crisis. Traditional healthcare is making clinicians miserable, and COVID has only accelerated the trend of overworked, disenchanted healthcare workers leaving in droves. Clinicians want more interactions with patients, and fewer with computer screens – call it “More face time, less FaceTime.” No new model will succeed unless the industry can more efficiently deploy its talent – arguably its most scarce and precious resource. V1C can help with alleviating the increasing burden and frustration borne by individual physicians in today’s status quo.

In healthcare, new technological approaches inevitably provoke no shortage of skepticism. Past lessons from Silicon Valley-driven fixes have led to understandable cynicism. But V1C is a different breed of animal. By building healthcare around the patient, not the clinic, V1C can make healthcare work better for patients, payers and providers. We’re at a fork in the road: we can revert back to a broken sick-care system, or dig in and do the hard work of figuring out how this future-forward healthcare system gets financed, organized and executed. As a field, we must find the courage and summon the energy to embrace this moment, and make it a moment of change.