Why Blindness Will Be the First Disorder Cured by Futuristic Treatments

A blind man with a cane goes for a walk at sunset. (© Prazis/Fotolia)

Stem cells and gene therapy were supposed to revolutionize biomedicine around the turn of the millennium and provide relief for desperate patients with incurable diseases. But for many, progress has been frustratingly slow. We still cannot, for example, regenerate damaged organs like a salamander regrows its tail, and genome engineering is more complicated than cutting and pasting letters in a word document.

"There are a number of things that make [the eye] ideal for new experimental therapies which are not true necessarily in other organs."

For blind people, however, the future of medicine is one step closer to reality. In December, the FDA approved the first gene therapy for an inherited disease—a mutation in the gene RPE65 that causes a rare form of blindness. Several clinical trials also show promise for treating various forms of retinal degeneration using stem cells.

"It's not surprising that the first gene therapy that was approved by the FDA was a therapy in the eye," says Bruce Conklin, a senior investigator at the San Francisco-based Gladstone Institutes, a nonprofit life science research organization, and a professor in the Medical Genetics and Molecular Pharmacology department at the University of California, San Francisco. "There are a number of things that make it ideal for new experimental therapies which are not true necessarily in other organs."

Physicians can easily see into the eye to check if a procedure worked or if it's causing problems. "The imaging technology within the eye is really unprecedented. You can't do this in someone's spinal cord or someone's brain cells or immune system," says Conklin, who is also deputy director of the Innovative Genomics Institute.

There's also a built-in control: researchers can test an intervention on one eye first. What's more, if something goes wrong, the risk of mortality is low, especially when compared to experimenting on the heart or brain. Most types of blindness are currently incurable, so the risk-to-reward ratio for patients is high. If a problem arises with the treatment their eyesight could get worse, but if they do nothing their vision will likely decline anyway. And if the treatment works, they may be able to see for the first time in years.

Gene Therapy

An additional appeal for testing gene therapy in the eye is the low risk for off-target effects, in which genome edits could result in unintended changes to other genes or in other cell types. There are a number of genes that are solely expressed in the eye and not in any other part of the body. Manipulating those genes will only affect cells in the eye, so concerns about the impact on other organs are minimal.

Ninety-three percent of patients who received the injection had improved vision just one month after treatment.

RPE65 is one such gene. It creates an enzyme that helps the eye convert light into an electrical signal that travels back to the brain. Patients with the mutation don't produce the enzyme, so visual signals are not processed. However, the retinal cells in the eye remain healthy for years; if you can restore the missing enzyme you can restore vision.

The newly approved therapy, developed by Spark Therapeutics, uses a modified virus to deliver RPE65 into the eye. A retinal surgeon injects the virus, which has been specially engineered to remove its disease-causing genes and instead carry the correct RPE65 gene, into the retina. There, it is sucked up by retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. The RPE cells are a particularly good target for injection because their job is to eat up and recycle rogue particles. Once inside the cell, the virus slips into the nucleus and releases the DNA. The RPE65 gene then goes to work, using the cell's normal machinery to produce the needed enzyme.

In the most recent clinical trial, 93 percent of patients who received the injection—who range in age from 4 to 44—had improved vision just one month after treatment. So far, the benefits have lasted at least two years.

"It's an exciting time for this class of diseases, where these people have really not had treatments," says Spark president and co-founder, Katherine High. "[Gene therapy] affords the possibility of treatment for diseases that heretofore other classes of therapeutics really have not been able to help."

Stem Cells

Another benefit of the eye is its immune privilege. In order to let light in, the eye must remain transparent. As a result, its immune system is dampened so that it won't become inflamed if outside particles get in. This means the eye is much less likely to reject cell transplants, so patients do not need to take immunosuppressant drugs.

One study generating buzz is a clinical trial in Japan that is the first and, so far, only test of induced pluripotent stem cells in the eye.

Henry Klassen, an assistant professor at UC Irvine, is taking advantage of the eye's immune privilege to transplant retinal progenitor cells into the eye to treat retinitis pigmentosa, an inherited disease affecting about 1 in 4000 people that eventually causes the retina to degenerate. The disease can stem from dozens of different genetic mutations, but the result is the same: RPE cells die off over the course of a few decades, leaving the patient blind by middle age. It is currently incurable.

Retinal progenitor cells are baby retinal cells that develop naturally from stem cells and will turn into one of several types of adult retinal cells. When transplanted into a patient's eye, the progenitor cells don't replace the lost retinal cells, but they do secrete proteins and enzymes essential for eye health.

"At the stage we get the retinal tissue it's immature," says Klassen. "They still have some flexibility in terms of which mature cells they can turn into. It's that inherent flexibility that gives them a lot of power when they're put in the context of a diseased retina."

Klassen's spin-off company, jCyte, sponsored the clinical trial with support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. The results from the initial study haven't been published yet, but Klassen says he considers it a success. JCyte is now embarking on a phase two trial to assess improvements in vision after the treatment, which will wrap up in 2021.

Another study generating buzz is a clinical trial in Japan that is the first and, so far, only test of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) in the eye. iPSC are created by reprogramming a patient's own skin cells into stem cells, circumventing any controversy around embryonic stem cell sources. In the trial, led by Masayo Takahashi at RIKEN, the scientists transplant retinal pigment epithelial cells created from iPSC into the retinas of patients with age-related macular degeneration. The first woman to receive the treatment is doing well, and her vision is stable. However, the second patient suffered a swollen retina as a result of the surgery. Despite this recent setback, Takahashi said last week that the trial would continue.

Botched Jobs

Although recent studies have provided patients with renewed hope, the field has not been without mishap. Most notably, an article in the New England Journal of Medicine last March described three patients who experienced severe side effects after receiving stem cell injections from a Florida clinic to treat age-related macular degeneration. Following the initial article, other reports came out about similar botched treatments. Lawsuits have been filed against US Stem Cell, the clinic that conducted the procedure, and the FDA sent them a warning letter with a long list of infractions.

"One red flag is that the clinics charge patients to take part in the treatment—something extremely unusual for legitimate clinical trials."

Ajay Kuriyan, an ophthalmologist and retinal specialist at the University of Rochester who wrote the paper, says that because details about the Florida trial are scarce, it's hard to say why the treatment caused the adverse reaction. His guess is that the stem cells were poorly prepared and not up to clinical standards.

Klassen agrees that small clinics like US Stem Cell do not offer the same caliber of therapy as larger clinical trials. "It's not the same cells and it's not the same technique and it's not the same supervision and it's not under FDA auspices. It's just not the same thing," he says. "Unfortunately, to the patient it might sound the same, and that's the tragedy for me."

For patients who are interested in joining a trial, Kuriyan listed a few things to watch out for. "One red flag is that the clinics charge patients to take part in the treatment—something extremely unusual for legitimate clinical trials," he says. "Another big red flag is doing the procedure in both eyes" at the same time. Third, if the only treatment offered is cell therapy. "These clinics tend to be sort of stand-alone clinics, and that's not very common for an actual big research study of this scale."

Despite the recent scandal, Klassen hopes that the success of his trial and others will continue to push the field forward. "It just takes so many decades to move this stuff along, even when you're trying to simplify it as much as possible," he says. "With all the heavy lifting that's been done, I hope the world's got the patience to get this through."

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

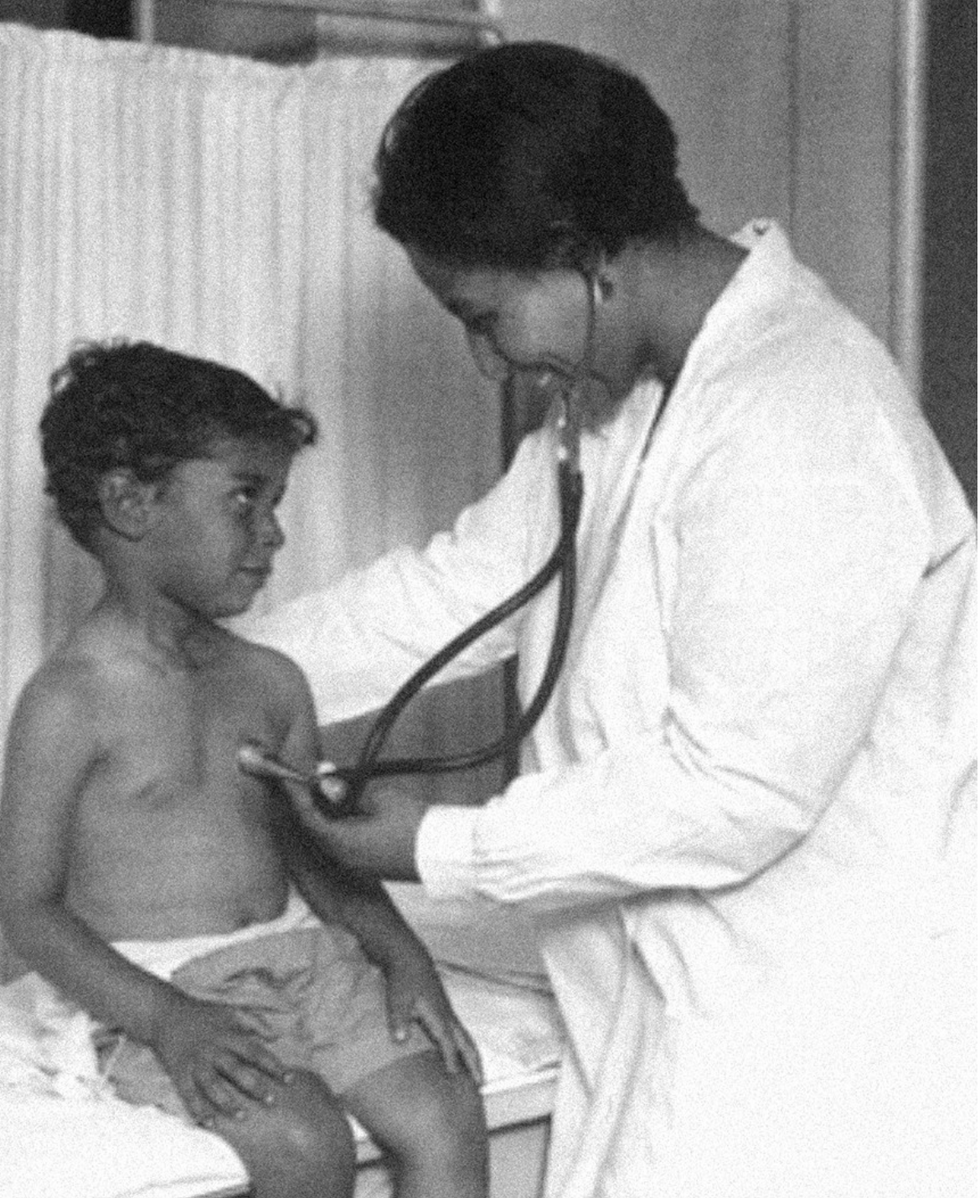

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

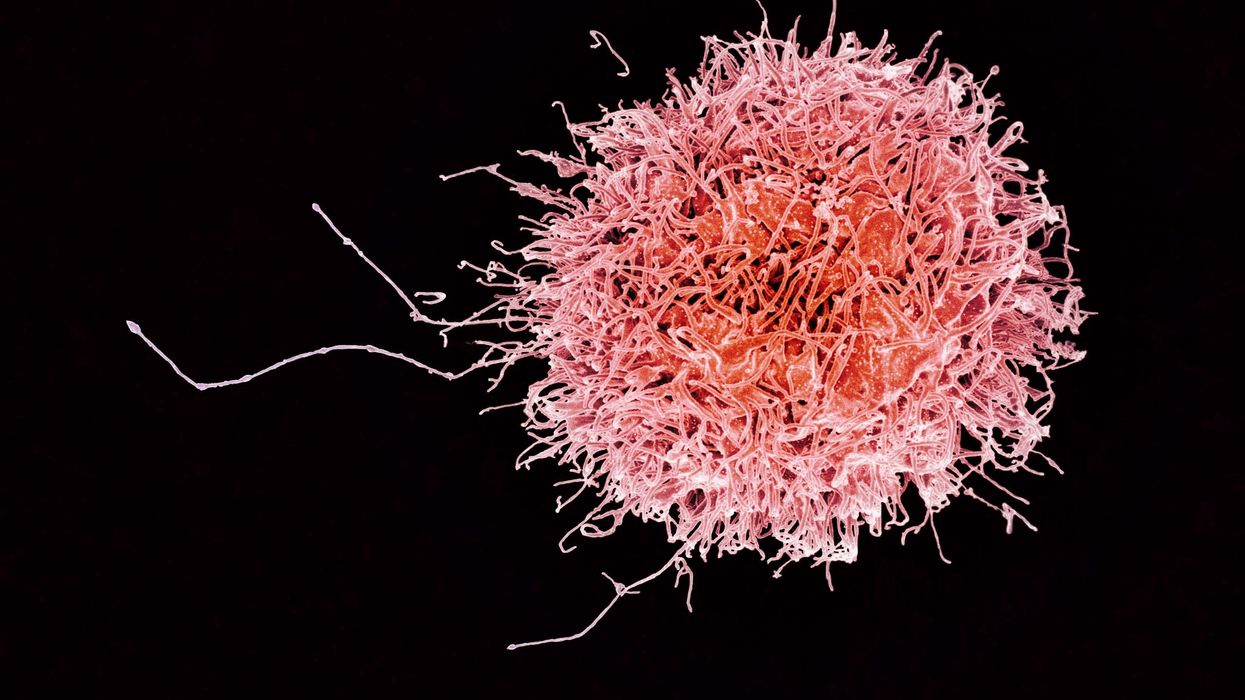

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business