Blood Money: Paying for Convalescent Plasma to Treat COVID-19

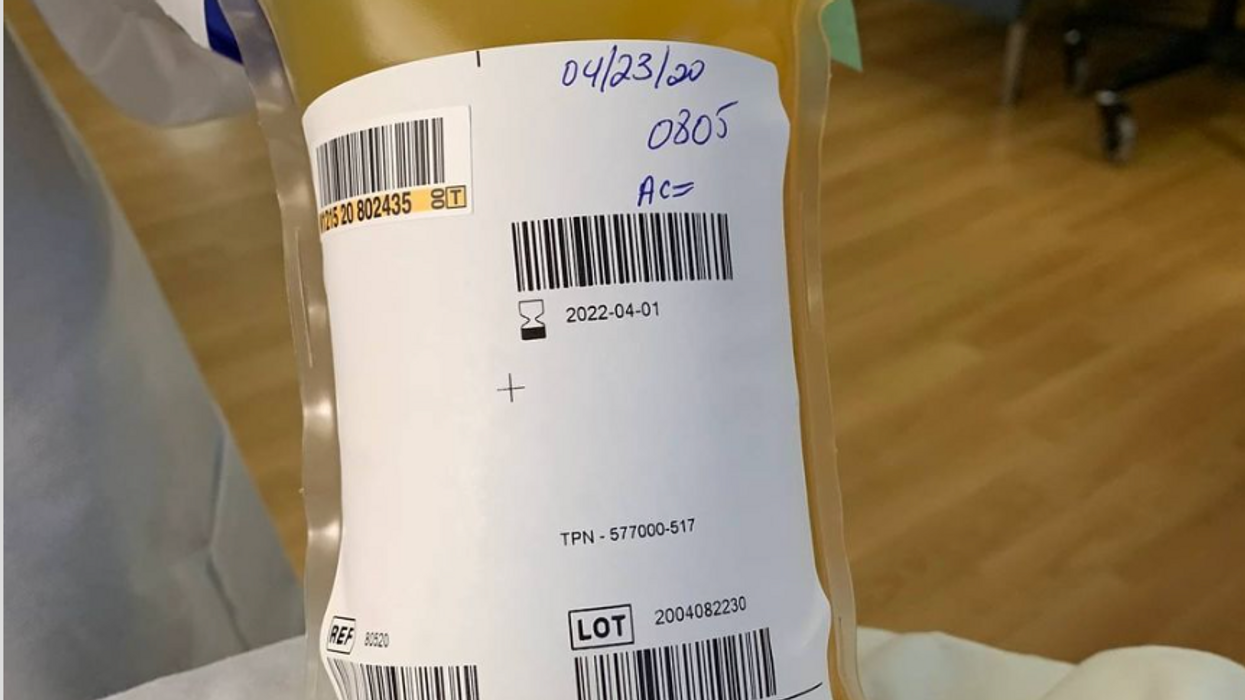

A bag of plasma that Tom Hanks donated back in April 2020 after his coronavirus infection. (He was not paid to donate.)

Convalescent plasma – first used to treat diphtheria in 1890 – has been dusted off the shelf to treat COVID-19. Does it work? Should we rely strictly on the altruism of donors or should people be paid for it?

The biologic theory is that a person who has recovered from a disease has chemicals in their blood, most likely antibodies, that contributed to their recovery, and transferring those to a person who is sick might aid their recovery. Whole blood won't work because there are too few antibodies in a single unit of blood and the body can hold only so much of it.

Plasma comprises about 55 percent of whole blood and is what's left once you take out the red blood cells that carry oxygen and the white blood cells of the immune system. Most of it is water but the rest is a complex mix of fats, salts, signaling molecules and proteins produced by the immune system, including antibodies.

A process called apheresis circulates the donors' blood through a machine that separates out the desired parts of blood and returns the rest to the donor. It takes several times the length of a regular whole blood donation to cycle through enough blood for the process. The end product is a yellowish concentration called convalescent plasma.

Recent History

It was used extensively during the great influenza epidemic off 1918 but fell out of favor with the development of antibiotics. Still, whenever a new disease emerges – SARS, MERS, Ebola, even antibiotic-resistant bacteria – doctors turn to convalescent plasma, often as a stopgap until more effective antibiotic and antiviral drugs are developed. The process is certainly safe when standard procedures for handling blood products are followed, and historically it does seem to be beneficial in at least some patients if administered early enough in the disease.

With few good treatment options for COVID-19, doctors have given convalescent plasma to more than a hundred thousand Americans and tens of thousand of people elsewhere, to mixed results. Placebo-controlled trials could give a clearer picture of plasma's value but it is difficult to enroll patients facing possible death when the flip of a coin will determine who will receive a saline solution or plasma.

And the plasma itself isn't some uniform pill stamped out in a factory, it's a natural product that is shaped by the immune history of the donor's body and its encounter not just with SARS-CoV-2 but a lifetime of exposure to different pathogens.

Researchers believe antibodies in plasma are a key factor in directly fighting the virus. But the variety and quantity of antibodies vary from donor to donor, and even over time from the same donor because once the immune system has cleared the virus from the body, it stops putting out antibodies to fight the virus. Often the quality and quantity of antibodies being given to a patient are not measured, making it somewhat hit or miss, which is why several companies have recently developed monoclonal antibodies, a single type of antibody found in blood that is effective against SARS-CoV-2 and that is multiplied in the lab for use as therapy.

Plasma may also contain other unknown factors that contribute to fighting disease, say perhaps signaling molecules that affect gene expression, which might affect the movement of immune cells, their production of antiviral molecules, or the regulation of inflammation. The complexity and lack of standardization makes it difficult to evaluate what might be working or not with a convalescent plasma treatment. Thus researchers are left with few clues about how to make it more effective.

Industrializing Plasma

Many Americans living along the border with Mexico regularly head south to purchase prescription drugs at a significant discount. Less known is the medical traffic the other way, Mexicans who regularly head north to be paid for plasma donations, which are prohibited in their country; the U.S. allows payment for plasma donations but not whole blood. A typical payment is about $35 for a donation but the sudden demand for convalescent plasma from people who have recovered from COVID-19 commands a premium price, sometimes as high as $200. These donors are part of a fast-growing plasma industry that surpassed $25 billion in 2018. The U.S. supplies about three-quarters of the world's needs for plasma.

Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free.

The pharmaceutical industry has shied away from natural products they cannot patent but they have identified simpler components from plasma, such as clotting factors and immunoglobulins, that have been turned into useful drugs from this raw material of plasma. While some companies have retooled to provide convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19, often paying those donors who have recovered a premium of several times the normal rate, most convalescent plasma has come as donations through traditional blood centers.

In April the Mayo Clinic, in cooperation with the FDA, created an expanded access program for convalescent plasma to treat COVID-19. It was meant to reduce the paperwork associated with gaining access to a treatment not yet approved by the FDA for that disease. Initially it was supposed to be for 5000 units but it quickly grew to more than twenty times that size. Michael Joyner, the head of the program, discussed that experience in an extended interview in September.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also created associated reimbursement codes, which became permanent in August.

Mayo published an analysis of the first 35,000 patients as a preprint in August. It concluded, "The relationships between mortality and both time to plasma transfusion, and antibody levels provide a signature that is consistent with efficacy for the use of convalescent plasma in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients."

It seemed to work best when given early in infection and in larger doses; a similar pattern has been seen in studies of monoclonal antibodies. A revised version will soon be published in a major medical journal. Some criticized the findings as not being from a randomized clinical trial.

Convalescent plasma is not the only intervention that seems to work better when used earlier in the course of disease. Recently the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly stopped a clinical trial of a monoclonal antibody in hospitalized COVID-19 patients when it became apparent it wasn't helping. It is continuing trials for patients who are less sick and begin treatment earlier, as well as in persons who have been exposed to the virus but not yet diagnosed as infected, to see if it might prevent infection. In November the FDA eased access to this drug outside of clinical trials, though it is not yet approved for sale.

Show Me the Money

The antibodies that seem to give plasma its curative powers are fragile proteins that the body produces to fight the virus. Production shuts down once the virus is cleared and the remaining antibodies survive only for a few weeks before the levels fade. [Vaccines are used to train immune cells to produce antibodies and other defenses to respond to exposure to future pathogens.] So they can be usefully harvested from a recovered patient for only a few short weeks or months before they decline precipitously. The question becomes, how does one mobilize this resource in that short window of opportunity?

The program run by the Mayo Clinic explains the process and criteria for donating convalescent plasma for COVID-19, as well as links to local blood centers equipped to handle those free donations. Commercial plasma centers also are advertising and paying for donations.

A majority of countries prohibit paying donors for blood or blood products, including India. But an investigation by India Today touted a black market of people willing to donate convalescent plasma for the equivalent of several hundred dollars. Officials vowed to prosecute, saying donations should be selfless.

But that enforcement threat seemed to be undercut when the health minister of the state of Assam declared "plasma donors will get preference in several government schemes including the government job interview." It appeared to be a form of compensation that far surpassed simple cash.

The small city of Rexburg, Idaho, with a population a bit over 50,000, overwhelmingly Mormon and home to a campus of Brigham Young University, at one point had one of the highest per capita rates of COVID-19 in the current wave of infection. Rumors circulated that some students were intentionally trying to become infected so they could later sell their plasma for top dollar, potentially as much as $200 a visit.

Troubled university officials investigated the allegations but could come up with nothing definitive; how does one prove intentionality with such an omnipresent yet elusive virus? They chalked it up to idle chatter, perhaps an urban legend, which might be associated with alcohol use on some other campus.

Doctors, hospitals, and drug companies are all rightly praised for their altruism in the fight against COVID-19, but they also get paid. Payment for whole blood donation in the U.S. is prohibited, and while payment for plasma is allowed, there is a stigma attached to payment and much plasma is donated for free. "Why do we expect the donors [of convalescent plasma] to be the only uncompensated people in the process? It really makes no sense," argues Mark Yarborough, an ethicist at the UC Davis School of Medicine in Sacramento.

"When I was in grad school, two of my closest friends, at least once a week they went and gave plasma. That was their weekend spending money," Yarborough recalls. He says upper and middle-income people may have the luxury of donating blood products but prohibiting people from selling their plasma is a bit paternalistic and doesn't do anything to improve the economic status of poor people.

"Asking people to dedicate two hours a week for an entire year in exchange for cookies and milk is demonstrably asking too much," says Peter Jaworski, an ethicist who teaches at Georgetown University.

He notes that companies that pay plasma donors have much lower total costs than do operations that rely solely on uncompensated donations. The companies have to spend less to recruit and retain donors because they increase payments to encourage regular repeat donations. They are able to more rationally schedule visits to maximize use of expensive apheresis equipment and medical personnel used for the collection.

It seems that COVID-19 has been with us forever, but in reality it is less than a year. We have learned much over that short time, can now better manage the disease, and have lower mortality rates to prove it. Just how much convalescent plasma may have contributed to that remains an open question. Access to vaccines is months away for many people, and even then some people will continue to get sick. Given the lack of proven treatments, it makes sense to keep plasma as part of the mix, and not close the door to any legitimate means to obtain it.

Breakthrough therapies are breaking patients' banks. Key changes could improve access, experts say.

Single-treatment therapies are revolutionizing medicine. But insurers and patients wonder whether they can afford treatment and, if they can, whether the high costs are worthwhile.

CSL Behring’s new gene therapy for hemophilia, Hemgenix, costs $3.5 million for one treatment, but helps the body create substances that allow blood to clot. It appears to be a cure, eliminating the need for other treatments for many years at least.

Likewise, Novartis’s Kymriah mobilizes the body’s immune system to fight B-cell lymphoma, but at a cost $475,000. For patients who respond, it seems to offer years of life without the cancer progressing.

These single-treatment therapies are at the forefront of a new, bold era of medicine. Unfortunately, they also come with new, bold prices that leave insurers and patients wondering whether they can afford treatment and, if they can, whether the high costs are worthwhile.

“Most pharmaceutical leaders are there to improve and save people’s lives,” says Jeremy Levin, chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics, and immediate past chairman of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. If the therapeutics they develop are too expensive for payers to authorize, patients aren’t helped.

“The right to receive care and the right of pharmaceuticals developers to profit should never be at odds,” Levin stresses. And yet, sometimes they are.

Leigh Turner, executive director of the bioethics program, University of California, Irvine, notes this same tension between drug developers that are “seeking to maximize profits by charging as much as the market will bear for cell and gene therapy products and other medical interventions, and payers trying to control costs while also attempting to provide access to medical products with promising safety and efficacy profiles.”

Why Payers Balk

Health insurers can become skittish around extremely high prices, yet these therapies often accompany significant overall savings. For perspective, the estimated annual treatment cost for hemophilia exceeds $300,000. With Hemgenix, payers would break even after about 12 years.

But, in 12 years, will the patient still have that insurer? Therein lies the rub. U.S. payers, are used to a “pay-as-you-go” model, in which the lifetime costs of therapies typically are shared by multiple payers over many years, as patients change jobs. Single treatment therapeutics eliminate that cost-sharing ability.

"As long as formularies are based on profits to middlemen…Americans’ healthcare costs will continue to skyrocket,” says Patricia Goldsmith, the CEO of CancerCare.

“There is a phenomenally complex, bureaucratic reimbursement system that has grown, layer upon layer, during several decades,” Levin says. As medicine has innovated, payment systems haven’t kept up.

Therefore, biopharma companies begin working with insurance companies and their pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which act on an insurer’s behalf to decide which drugs to cover and by how much, early in the drug approval process. Their goal is to make sophisticated new drugs available while still earning a return on their investment.

New Payment Models

Pay-for-performance is one increasingly popular strategy, Turner says. “These models typically link payments to evidence generation and clinically significant outcomes.”

A biotech company called bluebird bio, for example, offers value-based pricing for Zynteglo, a $2.8 million possible cure for the rare blood disorder known as beta thalassaemia. It generally eliminates patients’ need for blood transfusions. The company is so sure it works that it will refund 80 percent of the cost of the therapy if patients need blood transfusions related to that condition within five years of being treated with Zynteglo.

In his February 2023 State of the Union speech, President Biden proposed three pilot programs to reduce drug costs. One of them, the Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model calls on the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to establish outcomes-based agreements with manufacturers for certain cell and gene therapies.

A mortgage-style payment system is another, albeit rare, approach. Amortized payments spread the cost of treatments over decades, and let people change employers without losing their healthcare benefits.

Only about 14 percent of all drugs that enter clinical trials are approved by the FDA. Pharma companies, therefore, have an exigent need to earn a profit.

The new payment models that are being discussed aren’t solutions to high prices, says Bill Kramer, senior advisor for health policy at Purchaser Business Group on Health (PBGH), a nonprofit that seeks to lower health care costs. He points out that innovative pricing models, although well-intended, may distract from the real problem of high prices. They are attempts to “soften the blow. The best thing would be to charge a reasonable price to begin with,” he says.

Instead, he proposes making better use of research on cost and clinical effectiveness. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) conducts such research in the U.S., determining whether the benefits of specific drugs justify their proposed prices. ICER is an independent non-profit research institute. Its reports typically assess the degrees of improvement new therapies offer and suggest prices that would reflect that. “Publicizing that data is very important,” Kramer says. “Their results aren’t used to the extent they could and should be.” Pharmaceutical companies tend to price their therapies higher than ICER’s recommendations.

Drug Development Costs Soar

Drug developers have long pointed to the onerous costs of drug development as a reason for high prices.

A 2020 study found the average cost to bring a drug to market exceeded $1.1 billion, while other studies have estimated overall costs as high as $2.6 billion. The development timeframe is about 10 years. That’s because modern therapeutics target precise mechanisms to create better outcomes, but also have high failure rates. Only about 14 percent of all drugs that enter clinical trials are approved by the FDA. Pharma companies, therefore, have an exigent need to earn a profit.

Skewed Incentives Increase Costs

Pricing isn’t solely at the discretion of pharma companies, though. “What patients end up paying has much more to do with their PBMs than the actual price of the drug,” Patricia Goldsmith, CEO, CancerCare, says. Transparency is vital.

PBMs control patients’ access to therapies at three levels, through price negotiations, pricing tiers and pharmacy management.

When negotiating with drug manufacturers, Goldsmith says, “PBMs exchange a preferred spot on a formulary (the insurer’s or healthcare provider’s list of acceptable drugs) for cash-base rebates.” Unfortunately, 25 percent of the time, those rebates are not passed to insurers, according to the PBGH report.

Then, PBMs use pricing tiers to steer patients and physicians to certain drugs. For example, Kramer says, “Sometimes PBMs put a high-cost brand name drug in a preferred tier and a lower-cost competitor in a less preferred, higher-cost tier.” As the PBGH report elaborates, “(PBMs) are incentivized to include the highest-priced drugs…since both manufacturing rebates, as well as the administrative fees they charge…are calculated as a percentage of the drug’s price.

Finally, by steering patients to certain pharmacies, PBMs coordinate patients’ access to treatments, control patients’ out-of-pocket costs and receive management fees from the pharmacies.

Therefore, Goldsmith says, “As long as formularies are based on profits to middlemen…Americans’ healthcare costs will continue to skyrocket.”

Transparency into drug pricing will help curb costs, as will new payment strategies. What will make the most impact, however, may well be the development of a new reimbursement system designed to handle dramatic, breakthrough drugs. As Kramer says, “We need a better system to identify drugs that offer dramatic improvements in clinical care.”

In today's podcast episode, law professor Gaia Bernstein talks about the challenges of keeping control over our thoughts and actions, even when some powerful forces are pushing in the other direction.

Each afternoon, kids walk through my neighborhood, on their way back home from school, and almost all of them are walking alone, staring down at their phones. It's a troubling site. This daily parade of the zombie children just can’t bode well for the future.

That’s one reason I felt like Gaia Bernstein’s new book was talking directly to me. A law professor at Seton Hall, Gaia makes a strong argument that people are so addicted to tech at this point, we need some big, system level changes to social media platforms and other addictive technologies, instead of just blaming the individual and expecting them to fix these issues.

Gaia’s book is called Unwired: Gaining Control Over Addictive Technologies. It’s fascinating and I had a chance to talk with her about it for today’s podcast. At its heart, our conversation is really about how and whether we can maintain control over our thoughts and actions, even when some powerful forces are pushing in the other direction.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

We discuss the idea that, in certain situations, maybe it's not reasonable to expect that we’ll be able to enjoy personal freedom and autonomy. We also talk about how to be a good parent when it sometimes seems like our kids prefer to be raised by their iPads; so-called educational video games that actually don’t have anything to do with education; the root causes of tech addictions for people of all ages; and what kinds of changes we should be supporting.

Gaia is Seton’s Hall’s Technology, Privacy and Policy Professor of Law, as well as Co-Director of the Institute for Privacy Protection, and Co-Director of the Gibbons Institute of Law Science and Technology. She’s the founding director of the Institute for Privacy Protection. She created and spearheaded the Institute’s nationally recognized Outreach Program, which educated parents and students about technology overuse and privacy.

Professor Bernstein's scholarship has been published in leading law reviews including the law reviews of Vanderbilt, Boston College, Boston University, and U.C. Davis. Her work has been selected to the Stanford-Yale Junior Faculty Forum and received extensive media coverage. Gaia joined Seton Hall's faculty in 2004. Before that, she was a fellow at the Engelberg Center of Innovation Law & Policy and at the Information Law Institute of the New York University School of Law. She holds a J.S.D. from the New York University School of Law, an LL.M. from Harvard Law School, and a J.D. from Boston University.

Gaia’s work on this topic is groundbreaking I hope you’ll listen to the conversation and then consider pre-ordering her new book. It comes out on March 28.