Can Cultured Meat Save the Planet?

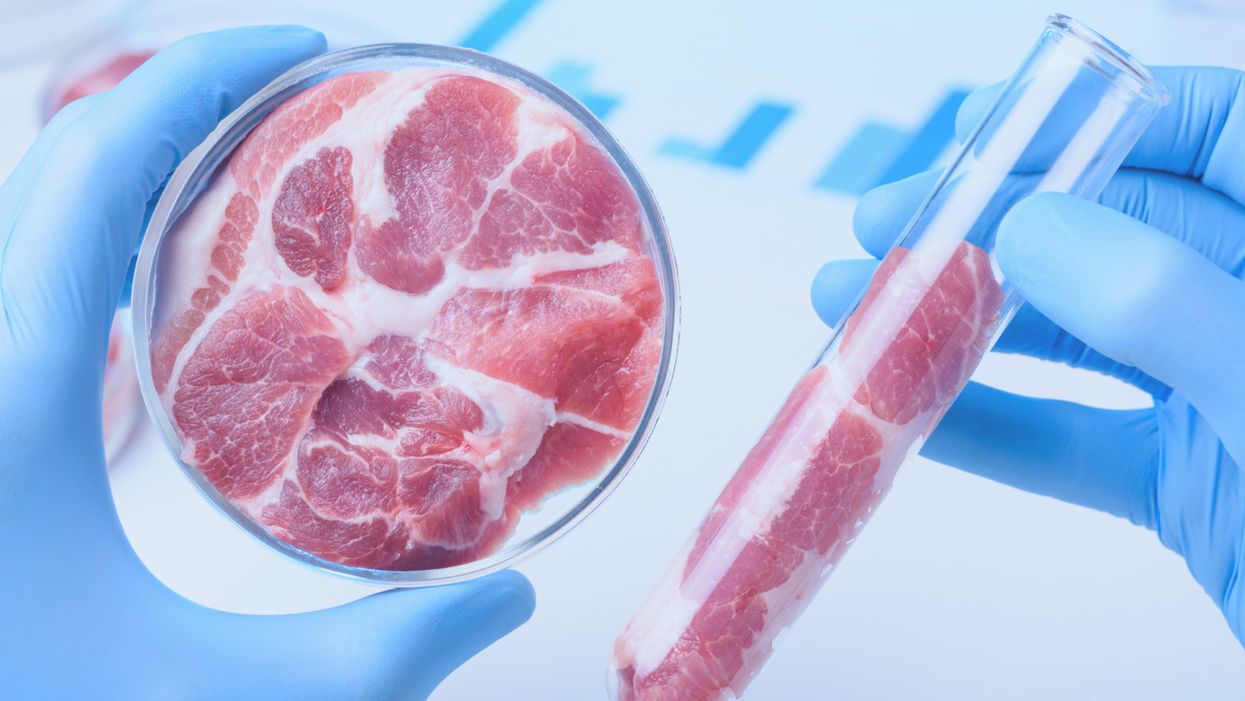

Lab-grown meat in a Petri dish and test tube.

In September, California governor Jerry Brown signed a bill mandating that by 2045, all of California's electricity will come from clean power sources. Technological breakthroughs in producing electricity from sun and wind, as well as lowering the cost of battery storage, have played a major role in persuading Californian legislators that this goal is realistic.

Even if the world were to move to an entirely clean power supply, one major source of greenhouse gas emissions would continue to grow: meat.

James Robo, the CEO of the Fortune 200 company NextEra Energy, has predicted that by the early 2020s, electricity from solar farms and giant wind turbines will be cheaper than the operating costs of coal-fired power plants, even when the cost of storage is included.

Can we therefore all breathe a sigh of relief, because technology will save us from catastrophic climate change? Not yet. Even if the world were to move to an entirely clean power supply, and use that clean power to charge up an all-electric fleet of cars, buses and trucks, one major source of greenhouse gas emissions would continue to grow: meat.

The livestock industry now accounts for about 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, roughly the same as the emissions from the tailpipes of all the world's vehicles. But whereas vehicle emissions can be expected to decline as hybrids and electric vehicles proliferate, global meat consumption is forecast to be 76 percent greater in 2050 than it has been in recent years. Most of that growth will come from Asia, especially China, where increasing prosperity has led to an increasing demand for meat.

Changing Climate, Changing Diets, a report from the London-based Royal Institute of International Affairs, indicates the threat posed by meat production. At the UN climate change conference held in Cancun in 2010, the participating countries agreed that to allow global temperatures to rise more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels would be to run an unacceptable risk of catastrophe. Beyond that limit, feedback loops will take effect, causing still more warming. For example, the thawing Siberian permafrost will release large quantities of methane, causing yet more warming and releasing yet more methane. Methane is a greenhouse gas that, ton for ton, warms the planet 30 times as much as carbon dioxide.

The quantity of greenhouse gases we can put into the atmosphere between now and mid-century without heating up the planet beyond 2°C – known as the "carbon budget" -- is shrinking steadily. The growing demand for meat means, however, that emissions from the livestock industry will continue to rise, and will absorb an increasing share of this remaining carbon budget. This will, according to Changing Climate, Changing Diets, make it "extremely difficult" to limit the temperature rise to 2°C.

One reason why eating meat produces more greenhouse gases than getting the same food value from plants is that we use fossil fuels to grow grains and soybeans and feed them to animals. The animals use most of the energy in the plant food for themselves, moving, breathing, and keeping their bodies warm. That leaves only a small fraction for us to eat, and so we have to grow several times the quantity of grains and soybeans that we would need if we ate plant foods ourselves. The other important factor is the methane produced by ruminants – mainly cattle and sheep – as part of their digestive process. Surprisingly, that makes grass-fed beef even worse for our climate than beef from animals fattened in a feedlot. Cattle fed on grass put on weight more slowly than cattle fed on corn and soybeans, and therefore do burp and fart more methane, per kilogram of flesh they produce.

Richard Branson has suggested that in 30 years, we will look back on the present era and be shocked that we killed animals en masse for food.

If technology can give us clean power, can it also give us clean meat? That term is already in use, by advocates of growing meat at the cellular level. They use it, not to make the parallel with clean energy, but to emphasize that meat from live animals is dirty, because live animals shit. Bacteria from the animals' guts and shit often contaminates the meat. With meat cultured from cells grown in a bioreactor, there is no live animal, no shit, and no bacteria from a digestive system to get mixed into the meat. There is also no methane. Nor is there a living animal to keep warm, move around, or grow body parts that we do not eat. Hence producing meat in this way would be much more efficient, and much cleaner, in the environmental sense, than producing meat from animals.

There are now many startups working on bringing clean meat to market. Plant-based products that have the texture and taste of meat, like the "Impossible Burger" and the "Beyond Burger" are already available in restaurants and supermarkets. Clean hamburger meat, fish, dairy, and other animal products are all being produced without raising and slaughtering a living animal. The price is not yet competitive with animal products, but it is coming down rapidly. Just this week, leading officials from the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture have been meeting to discuss how to regulate the expected production and sale of meat produced by this method.

When Kodak, which once dominated the sale and processing of photographic film, decided to treat digital photography as a threat rather than an opportunity, it signed its own death warrant. Tyson Foods and Cargill, two of the world's biggest meat producers, are not making the same mistake. They are investing in companies seeking to produce meat without raising animals. Justin Whitmore, Tyson's executive vice-president, said, "We don't want to be disrupted. We want to be part of the disruption."

That's a brave stance for a company that has made its fortune from raising and killing tens of billions of animals, but it is also an acknowledgement that when new technologies create products that people want, they cannot be resisted. Richard Branson, who has invested in the biotech company Memphis Meats, has suggested that in 30 years, we will look back on the present era and be shocked that we killed animals en masse for food. If that happens, technology will have made possible the greatest ethical step forward in the history of our species, saving the planet and eliminating the vast quantity of suffering that industrial farming is now inflicting on animals.

Interventions in health and safety often yield results that are the opposite of what policymakers were hoping for. Officials can take a science-based approach by measuring what really works instead of relying on gut intuitions.

nudgesYou are driving along the highway and see an electronic sign that reads: “3,238 traffic deaths this year.” Do you think this reminder of roadside mortality would change how you drive? According to a recent, peer-reviewed study in Science, seeing that sign would make you more likely to crash. That’s ironic, given that the sign’s creators assumed it would make you safer.

The study, led by a pair of economists at the University of Toronto and University of Minnesota, examined seven years of traffic accident data from 880 electric highway sign locations in Texas, which experienced 4,480 fatalities in 2021. For one week of each month, the Texas Department of Transportation posts the latest fatality messages on signs along select traffic corridors as part of a safety campaign. Their logic is simple: Tell people to drive with care by reminding them of the dangers on the road.

But when the researchers looked at the data, they found that the number of crashes increased by 1.52 percent within three miles of these signs when compared with the same locations during the same month in previous years when signs did not show fatality information. That impact is similar to raising the speed limit by four miles or decreasing the number of highway troopers by 10 percent.

The scientists calculated that these messages contributed to 2,600 additional crashes and 16 deaths annually. They also found a social cost, meaning the financial expense borne by society as a whole due to these crashes, of $377 million per year, in Texas alone.

The cause, they argue, is distracted driving. Much like incoming texts or phone calls, these “in-your-face” messages grab your attention and undermine your focus on the road. The signs are particularly distracting and dangerous because, in communicating that many people died doing exactly what you are doing, they cause anxiety. Supporting this hypothesis, the scientists discovered that crashes increase when the signs report higher numbers of deaths. Thus, later in the year, as that total mortality figure goes up, so do the percentage of crashes.

Boomerang effects happen when those with authority, in government or business, fail to pay attention to the science. These leaders rely on armchair psychology and gut intuitions on what should work, rather than measuring what does work.

That change over time is not simply a function of changing weather, the study’s authors observed. They also found that the increase in car crashes is greatest in more complex road segments, which require greater focus to navigate.

The overall findings represent what behavioral scientists like myself call a “boomerang effect,” meaning an intervention that produces consequences opposite to those intended. Unfortunately, these effects are all too common. Between 1998 and 2004, Congress funded the $1 billion National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign, which famously boomeranged. Using professional advertising and public relations firms, the campaign bombarded kids aged 9 to 18 with anti-drug messaging, focused on marijuana, on TV, radio, magazines, and websites. A 2008 study funded by the National Institutes of Health found that children and teens saw these ads two to three times per week. However, more exposure to this advertising increased the likelihood that youth used marijuana. Why? Surveys and interviews suggested that young people who saw the ads got the impression that many of their peers used marijuana. As a result, they became more likely to use the drug themselves.

Boomerang effects happen when those with authority, in government or business, fail to pay attention to the science. These leaders rely on armchair psychology and gut intuitions on what should work, rather than measuring what does work.

To be clear, message campaigns—whether on electronic signs or through advertisements—can have a substantial effect on behavior. Extensive research reveals that people can be influenced by “nudges,” which shape the environment to influence their behavior in a predictable manner. For example, a successful campaign to reduce car accidents involved sending smartphone notifications that helped drivers evaluate their performance after each trip. These messages informed drivers of their personal average and best performance, as measured by accelerometers and gyroscopes. The campaign, which ran over 21 months, significantly reduced accident frequency.

Nudges work best when rigorously tested with small-scale experiments that evaluate their impact. Because behavioral scientists are infrequently consulted in creating these policies, some studies suggest that only 62 percent have a statistically significant effect. Other research reveals that up to 15 percent of desired interventions may backfire.

In the case of roadside mortality signage, the data are damning. The new research based on the Texas signs aligns with several past studies. For instance, research has shown that increasing people’s anxiety causes them to drive worse. Another, a Virginia Tech study in a laboratory setting, found that showing drivers fatality messages increased what psychologists call “cognitive load,” or the amount of information your brain is processing, with emotionally-salient information being especially burdensome and preoccupying, thus causing more distraction.

Nonetheless, Texas, along with at least 28 other states, has pursued mortality messaging campaigns since 2012, without testing them effectively. Behavioral science is critical here: when road signs are tested by people without expertise in how minds work, the results are often counterproductive. For example, the Virginia Tech research looked at road signs that used humor, popular culture, sports, and other nontraditional themes with the goal of provoking an emotional response. When they measured how participants responded to these signs, they noticed greater cognitive activation and attention in the brain. Thus, the researchers decided, the signs worked. But a behavioral scientist would note that increased attention likely contributes to the signs’ failure. As the just-published study in Science makes clear, distracting, emotionally-loaded signs are dangerous to drivers.

But there is good news. First, in most cases, it’s very doable to run an effective small-scale study testing an intervention. States could set up a safety campaign with a few electric signs in a diversity of settings and evaluate the impact over three months on driver crashes after seeing the signs. Policymakers could ask researchers to track the data as they run ads for a few months in a variety of nationally representative markets for a few months and assess their effectiveness. They could also ask behavioral scientists whether their proposals are well designed, whether similar policies have been tried previously in other places, and how these policies have worked in practice.

Everyday citizens can write to and call their elected officials to ask them to make this kind of research a priority before embracing an untested safety campaign. More broadly, you can encourage them to avoid relying on armchair psychology and to test their intuitions before deploying initiatives that might place the public under threat.

Why we should put insects on the menu

Insects for sale at a market in Cambodia.

I walked through the Dong Makkhai forest-products market, just outside of Vientiane, the laid-back capital of the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic or Lao PDR. Piled on rough display tables were varieties of six-legged wildlife–grasshoppers, small white crickets, house crickets, mole crickets, wasps, wasp eggs and larvae, dragonflies, and dung beetles. Some were roasted or fried, but in a few cases, still alive and scrabbling at the bottom of deep plastic bowls. I crunched on some fried crickets and larvae.

One stall offered Giant Asian hornets, both babies and adults. I suppressed my inner squirm and, in the interests of world food security and equity, accepted an offer of the soft, velvety larva; they were smooth on the tongue and of a pleasantly cool, buttery-custard consistency. Because the seller had already given me a free sample, I felt obliged to buy a chunk of the nest with larvae and some dead adults, which the seller mixed with kaffir lime leaves.

The year was 2016 and I was in Lao PDR because Veterinarians without Borders/Vétérinaires sans Frontières-Canada had initiated a project on small-scale cricket farming. The intent was to organize and encourage rural women to grow crickets as a source of supplementary protein and sell them at the market for cash. As a veterinary epidemiologist, I had been trained to exterminate disease spreading insects—Lyme disease-carrying ticks, kissing bugs that carry American Sleeping Sickness and mosquitoes carrying malaria, West Nile and Zika. Now, as part of a global wave promoting insects as a sustainable food source, I was being asked to view arthropods as micro-livestock, and devise management methods to keep them alive and healthy. It was a bit of a mind-bender.

The 21st century wave of entomophagy, or insect eating, first surged in the early 2010s, promoted by a research centre in Wageningen, a university in the Netherlands, conferences organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and enthusiastic endorsements by culinary adventurers and celebrities from Europeanized cultures. Headlines announced that two billion people around the world already ate insects, and that if everyone adopted entomophagy we could reduce greenhouse gases, mitigate climate change, and reign in profligate land and water use associated with industrial livestock production.

Furthermore, eating insects was better for human health than eating beef. If we were going to feed the estimated nine billion people with whom we will share the earth in 2050, we would need to make some radical changes in our agriculture and food systems. As one author proclaimed, entomophagy presented us with a last great chance to save the planet.

In 2010, in Kunming, a friend had served me deep-fried bamboo worms. I ate them to be polite. They tasted like French fries, but with heads.

The more recent data suggests that the number of people who eat insects in various forms, though sizeable, may be closer to several hundreds of millions. I knew that from several decades of international veterinary work. Sometimes, for me, insect eating has been simply a way of acknowledging cultural diversity. In 2010, in Kunming, a friend had served me deep-fried bamboo worms. I ate them to be polite. They tasted like French fries, but with heads. My friend said he preferred them chewier. I never thought about them much after that. I certainly had not thought about them as ingredients for human health.

Is consuming insects good for human health? Researchers over the past decade have begun to tease that apart. Some think it might not be useful to use the all-encompassing term insect at all; we don’t lump cows, pigs, chickens into one culinary category. Which insects are we talking about? What are they fed? Were they farmed or foraged? Which stages of the insects are we eating? Do we eat them directly or roasted and ground up?

The overall research indicates that, in general, the usual farmed insects (crickets, locusts, mealworms, soldier fly larvae) have high levels of protein and other important nutrients. If insects are foraged by small groups in Laos, they provide excellent food supplements. Large scale foraging in response to global markets can be incredibly destructive, but soldier fly larvae fed on food waste and used as a substitute for ground up anchovies for farmed fish (as Enterra Feed in Canada does) improves ecological sustainability.

Entomophagy alone might not save the planet, but it does give us an unprecedented opportunity to rethink how we produce and harvest protein.

The author enjoys insects from the Dong Makkhai forest-products market, just outside of Vientiane, the capital of the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic.

David Waltner-Toews

Between 1961 and 2018, world chicken production increased from 4 billion to 20 billion, pork from 200 million to over 100 billion pigs, human populations doubled from 3.5 billion to more than 7 billion, and life expectancy (on average) from 52 to 72 years. These dramatic increases in food production are the result of narrowly focused scientific studies, identifying specific nutrients, antibiotics, vaccines and genetics. What has been missing is any sort of peripheral vision: what are the unintended consequences of our narrowly defined success?

If we look more broadly, we can see that this narrowly defined success led to industrial farming, which caused wealth, health and labor inequities; polluted the environment; and created grounds for disease outbreaks. Recent generations of Europeanized people inherited the ideas of eating cows, pigs and chickens, along with their products, so we were focused only on growing them as efficiently as possible. With insects, we have an exciting chance to start from scratch. Because, for Europeanized people, insect eating is so strange, we are given the chance to reimagine our whole food system in consultation with local experts in Asia and Africa (many of them villagers), and to bring together the best of both locally adapted food production and global distribution.

For this to happen, we will need to change the dietary habits of the big meat eaters. How can we get accustomed to eating bugs? There’s no one answer, but there are a few ways. In many cases, insects are ground up and added as protein supplements to foods like crackers or bars. In certain restaurants, the chefs want you to get used to seeing the bugs as you eat them. At Le Feston Nu in Paris, the Arlo Guthrie look-alike bartender poured me a beer and brought out five small plates, each featuring a different insect in a nest of figs, sun-dried tomatoes, raisins, and chopped dried tropical fruits: buffalo worms, crickets, large grasshoppers (all just crunchy and no strong flavour, maybe a little nutty), small black ants (sour bite), and fat grubs with a beak, which I later identified as palm weevil larvae, tasting a bit like dried figs.

Some entomophagy advertising has used esthetically pleasing presentations in classy restaurants. In London, at the Archipelago restaurant, I dined on Summer Nights (pan fried chermoula crickets, quinoa, spinach and dried fruit), Love-Bug Salad (baby greens with an accompanying dish of zingy, crunchy mealworms fried in olive oil, chilis, lemon grass, and garlic), Bushman’s Cavi-Err (caramel mealworms, bilinis, coconut cream and vodka jelly), and Medieaval Hive (brown butter ice cream, honey and butter caramel sauce and a baby bee drone).

The Archipelago restaurant in London serves up a Love-Bug Salad: baby greens with an accompanying dish of zingy, crunchy mealworms fried in olive oil, chilis, lemon grass, and garlic.

David Waltner-Toews

Some chefs, like Tokyo-based Shoichi Uchiyama, try to entice people with sidewalk cooking lessons. Uchiyama's menu included hornet larvae, silkworm pupae, and silkworms. The silkworm pupae were white and pink and yellow. We snipped off the ends and the larvae dropped out. My friend Zen Kawabata roasted them in a small pan over a camp stove in the street to get the "chaff" off. We made tea from the feces of worms that had fed on cherry blossoms—the tea smelled of the blossoms. One of Uchiyama-san’s assistants made noodles from buckwheat dough that included powdered whole bees.

At a book reading in a Tokyo bookstore, someone handed me a copy of the Japanese celebrity scandal magazine Friday, opened to an article celebrating the “charms of insect eating.” In a photo, scantily-clad girls were drinking vodka and nibbling giant water bugs dubbed as toe-biters, along with pickled and fried locusts and butterfly larvae. If celebrities embraced bug-eating, others might follow. When asked to prepare an article on entomophagy for the high fashion Sorbet Magazine, I started by describing a clip of Nicole Kidman delicately snacking on insects.

Taking a page from the success story of MacDonald’s, we might consider targeting children and school lunches. Kids don’t lug around the same dietary baggage as the grownups, and they can carry forward new eating habits for the long term. When I offered roasted crickets to my grandchildren, they scarfed them down. I asked my five-year-old granddaughter what she thought: she preferred the mealworms to the crickets – they didn’t have legs that caught in her teeth.

Entomo Farms in Ontario, the province where I live, was described in 2015 by Canadian Business magazine as North America’s largest supplier of edible insects for human consumption. When visiting, I popped some of their roasted crickets into my mouth. They were crunchy, a little nutty. Nothing to get squeamish over. Perhaps the human consumption is indeed growing—my wife, at least, has joined me in my entomophagy adventures. When we celebrated our wedding anniversary at the Public Bar and Restaurant in Brisbane, Australia, the “Kang Kong Worms” and “Salmon, Manuka Honey, and Black Ants” seemed almost normal. Of course, the champagne helped.