Can Spare Parts from Pigs Solve Our Organ Shortage?

A decellularized small porcine liver.

Jennifer Cisneros was 18 years old, commuting to college from her family's home outside Annapolis, Maryland, when she came down with what she thought was the flu. Over the following weeks, however, her fatigue and nausea worsened, and her weight began to plummet. Alarmed, her mother took her to see a pediatrician. "When I came back with the urine cup, it was orange," Cisneros recalls. "He was like, 'Oh, my God. I've got to send you for blood work.'"

"Eventually, we'll be better off than with a human organ."

Further tests showed that her kidneys were failing, and at Johns Hopkins Hospital, a biopsy revealed the cause: Goodpasture syndrome (GPS), a rare autoimmune disease that attacks the kidneys or lungs. Cisneros was put on dialysis to filter out the waste products that her body could no longer process, and given chemotherapy and steroids to suppress her haywire immune system.

The treatment drove her GPS into remission, but her kidneys were beyond saving. At 19, Cisneros received a transplant, with her mother as donor. Soon, she'd recovered enough to return to school; she did some traveling, and even took up skydiving and parasailing. Then, after less than two years, rejection set in, and the kidney had to be removed.

She went back on dialysis until she was 26, when a stranger learned of her plight and volunteered to donate. That kidney lasted four years, but gave out after a viral infection. Since 2015, Cisneros—now 32, and working as an office administrator between thrice-weekly blood-filtering sessions—has been waiting for a replacement.

She's got plenty of company. About 116,000 people in the United States currently need organ transplants, but fewer than 35,000 organs become available every year. On average, 20 people on the waiting list die each day. And despite repeated campaigns to boost donorship, the gap shows no sign of narrowing.

"This is going to revolutionize medicine, in ways we probably can't yet appreciate."

For decades, doctors and scientists have envisioned a radical solution to the shortage: harvesting other species for spare parts. Xenotransplantation, as the practice is known, could provide an unlimited supply of lifesaving organs for patients like Cisneros. Those organs, moreover, could be altered by genetic engineering or other methods to reduce the danger of rejection—and thus to eliminate the need for immunosuppressive drugs, whose potential side effects include infections, diabetes, and cancer. "Eventually, we'll be better off than with a human organ," says David Cooper, MD, PhD, co-director of the xenotransplant program at the University of Alabama School of Medicine. "This is going to revolutionize medicine, in ways we probably can't yet appreciate."

Recently, progress toward that revolution has accelerated sharply. The cascade of advances began in April 2016, when researchers at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) reported keeping pig hearts beating in the abdomens of five baboons for a record-breaking mean of 433 days, with one lasting more than two-and-a-half years. Then a team at Emory University announced that a pig kidney sustained a rhesus monkey for 435 days before being rejected, nearly doubling the previous record. At the University of Munich, in Germany, researchers doubled the record for a life-sustaining pig heart transplant in a baboon (replacing the animal's own heart) to 90 days. Investigators at the Salk Institute and the University of California, Davis, declared that they'd grown tissue in pig embryos using human stem cells—a first step toward cultivating personalized replacement organs. The list goes on.

Such breakthroughs, along with a surge of cash from biotech investors, have propelled a wave of bullish media coverage. Yet this isn't the first time that xenotransplantation has been touted as the next big thing. Twenty years ago, the field seemed poised to overcome its final hurdles, only to encounter a setback from which it is just now recovering.

Which raises a question: Is the current excitement justified? Or is the hype again outrunning the science?

A History of Setbacks

The idea behind xenotransplantation dates back at least as far as the 17th century, when French physician Jean-Baptiste Denys tapped the veins of sheep and cows to perform the first documented human blood transfusions. (The practice was banned after two of the four patients died, probably from an immune reaction.) In the 19th century, surgeons began transplanting corneas from pigs and other animals into humans, and using skin xenografts to aid in wound healing; despite claims of miraculous cures, medical historians believe those efforts were mostly futile. In the 1920s and '30s, thousands of men sought renewed vigor through testicular implants from monkeys or goats, but the fad collapsed after studies showed the effects to be imaginary.

Research shut down when scientists discovered a virus in pig DNA that could infect human cells.

After the first successful human organ transplant in 1954—of a kidney, passed between identical twin sisters—the limited supply of donor organs brought a resurgence of interest in animal sources. Attention focused on nonhuman primates, our species' closest evolutionary relatives. At Tulane University, surgeon Keith Reemstma performed the first chimpanzee-to-human kidney transplants in 1963 and '64. Although one of the 13 patients lived for nine months, the rest died within a few weeks due to organ rejection or infections. Other surgeons attempted liver and heart xenotransplants, with similar results. Even the advent of the first immunosuppressant drug, cyclosporine, in 1983, did little to improve survival rates.

In the 1980s, Cooper—a pioneering heart transplant surgeon who'd embraced the dream of xenotransplantation—began arguing that apes and monkeys might not be the best donor animals after all. "First of all, there's not enough of them," he explains. "They breed in ones and twos, and take years to grow to full size. Even then, their hearts aren't big enough for a 70-kg. patient." Pigs, he suggested, would be a more practical alternative. But when he tried transplanting pig organs into nonhuman primates (as surrogates for human recipients), they were rejected within minutes.

In 1992, Cooper's team identified a sugar on the surface of porcine cells, called alpha-1,3-galactose (a-gal), as the main target for the immune system's attack. By then, the first genetically modified pigs had appeared, and biotech companies—led by the Swiss-based pharma giant Novartis—began pouring millions of dollars into developing one whose organs could elude or resist the human body's defenses.

Disaster struck five years later, when scientists reported that a virus whose genetic code was written into pig DNA could infect human cells in lab experiments. Although there was no evidence that the virus, known as PERV (for porcine endogenous retrovirus) could cause disease in people, the discovery stirred fears that xenotransplants might unleash a deadly epidemic. Facing scrutiny from government regulators and protests from anti-GMO and animal-rights activists, Novartis "pulled out completely," Cooper recalls. "They slaughtered all their pigs and closed down their research facility." Competitors soon followed suit.

The riddles surrounding animal-to-human transplants are far from fully solved.

A New Chapter – With New Questions

Yet xenotransplantation's visionaries labored on, aided by advances in genetic engineering and immunosuppression, as well as in the scientific understanding of rejection. In 2003, a team led by Cooper's longtime colleague David Sachs, at Harvard Medical School, developed a pig lacking the gene for a-gal; over the next few years, other scientists knocked out genes expressing two more problematic sugars. In 2013, Muhammad Mohiuddin, then chief of the transplantation section at the NHLBI, further modified a group of triple-knockout pigs, adding genes that code for two human proteins: one that shields cells from attack by an immune mechanism known as the complement system; another that prevents harmful coagulation. (It was those pigs whose hearts recently broke survival records when transplanted into baboon bellies. Mohiuddin has since become director of xenoheart transplantation at the University of Maryland's new Center for Cardiac Xenotransplantation Research.) And in August 2017, researchers at Harvard Medical School, led by George Church and Luhan Yang, announced that they'd used CRISPR-cas9—an ultra-efficient new gene-editing technique—to disable 62 PERV genes in fetal pig cells, from which they then created cloned embryos. Of the 37 piglets born from this experiment, none showed any trace of the virus.

Still, the riddles surrounding animal-to-human transplants are far from fully solved. One open question is what further genetic manipulations will be necessary to eliminate all rejection. "No one is so naïve as to think, 'Oh, we know all the genes—let's put them in and we are done,'" biologist Sean Stevens, another leading researcher, told the The New York Times. "It's an iterative process, and no one that I know can say whether we will do two, or five, or 100 iterations." Adding traits can be dangerous as well; pigs engineered to express multiple anticoagulation proteins, for example, often die of bleeding disorders. "We're still finding out how many you can do, and what levels are acceptable," says Cooper.

Another question is whether PERV really needs to be disabled. Cooper and some of his colleagues note that pig tissue has long been used for various purposes, such as artificial heart valves and wound-repair products, without incident; requiring the virus to be eliminated, they argue, will unnecessarily slow progress toward creating viable xenotransplant organs and the animals that can provide them. Others disagree. "You cannot do anything with pig organs if you do not remove them," insists bioethicist Jeantine Lunshof, who works with Church and Yang at Harvard. "The risk is simply too big."

"We've removed the cells, so we don't have to worry about latent viruses."

Meanwhile, over the past decade, other approaches to xenotransplantation have emerged. One is interspecies blastocyst complementation, which could produce organs genetically identical to the recipient's tissues. In this method, genes that produce a particular organ are knocked out in the donor animal's embryo. The embryo is then injected with pluripotent stem cells made from the tissue of the intended recipient. The stem cells move in to fill the void, creating a functioning organ. This technique has been used to create mouse pancreases in rats, which were then successfully transplanted into mice. But the human-pig "chimeras" recently created by scientists were destroyed after 28 days, and no one plans to bring such an embryo to term anytime soon. "The problem is that cells don't stay put; they move around," explains Father Kevin FitzGerald, a bioethicist at Georgetown University. "If human cells wind up in a pig's brain, that leads to a really interesting conundrum. What if it's self-aware? Are you going to kill it?"

Much further along, and less ethically fraught, is a technique in which decellularized pig organs act as a scaffold for human cells. A Minnesota-based company called Miromatrix Medical is working with Mayo Clinic researchers to develop this method. First, a mild detergent is pumped through the organ, washing away all cellular material. The remaining structure, composed mainly of collagen, is placed in a bioreactor, where it's seeded with human cells. In theory, each type of cell that normally populates the organ will migrate to its proper place (a process that naturally occurs during fetal development, though it remains poorly understood). One potential advantage of this system is that it doesn't require genetically modified pigs; nor will the animals have to be raised under controlled conditions to avoid exposure to transmissible pathogens. Instead, the organs can be collected from ordinary slaughterhouses.

Recellularized livers in bioreactors

(Courtesy of Miromatrix)

"We've removed the cells, so we don't have to worry about latent viruses," explains CEO Jeff Ross, who describes his future product as a bioengineered human organ rather than a xeno-organ. That makes PERV a nonissue. To shorten the pathway to approval by the Food and Drug Administration, the replacement cells will initially come from human organs not suitable for transplant. But eventually, they'll be taken from the recipient (as in blastocyst complementation), which should eliminate the need for immunosuppression.

Clinical trials in xenotransplantation may begin as early as 2020.

Miromatrix plans to offer livers first, followed by kidneys, hearts, and eventually lungs and pancreases. The company recently succeeded in seeding several decellularized pig livers with human and porcine endothelial cells, which flocked obediently to the blood vessels. Transplanted into young pigs, the organs showed unimpaired circulation, with no sign of clotting. The next step is to feed all four liver cell types back into decellularized livers, and see if the transplanted organs will keep recipient pigs alive.

Ross hopes to launch clinical trials by 2020, and several other groups (including Cooper's, which plans to start with kidneys) envision a similar timeline. Investors seem to share their confidence. The biggest backer of xenotransplantation efforts is United Therapeutics, whose founder and co-CEO, Martine Rothblatt, has a daughter with a lung condition that may someday require a transplant; since 2011, the biotech firm has poured at least $100 million into companies pursuing such technologies, while supporting research by Cooper, Mohiuddin, and other leaders in the field. Church and Yang, at Harvard, have formed their own company, eGenesis, bringing in a reported $40 million in funding; Miromatrix has raised a comparable amount.

It's impossible to predict who will win the xenotransplantation race, or whether some new obstacle will stop the competition in its tracks. But Jennifer Cisneros is rooting for all the contestants. "These technologies could save my life," she says. If she hasn't found another kidney before trials begin, she has just one request: "Sign me up."

Scientists Are Working to Decipher the Puzzle of ‘Broken Heart Syndrome’

Elaine Kamil had just returned home after a few days of business meetings in 2013 when she started having chest pains. At first Kamil, then 66, wasn't worried—she had had some chest pain before and recently went to a cardiologist to do a stress test, which was normal.

"I can't be having a heart attack because I just got checked," she thought, attributing the discomfort to stress and high demands of her job. A pediatric nephrologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, she takes care of critically ill children who are on dialysis or are kidney transplant patients. Supporting families through difficult times and answering calls at odd hours is part of her daily routine, and often leaves her exhausted.

She figured the pain would go away. But instead, it intensified that night. Kamil's husband drove her to the Cedars-Sinai hospital, where she was admitted to the coronary care unit. It turned out she wasn't having a heart attack after all. Instead, she was diagnosed with a much less common but nonetheless dangerous heart condition called takotsubo syndrome, or broken heart syndrome.

A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is obstructed—such as when an artery is blocked—causing heart muscle tissue to die. In takotsubo syndrome, the blood flow isn't blocked, but the heart doesn't pump it properly. The heart changes its shape and starts to resemble a Japanese fishing device called tako-tsubo, a clay pot with a wider body and narrower mouth, used to catch octopus.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks," explains Noel Bairey Merz, the cardiologist at Cedar Sinai who Kamil went to see after she was discharged.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks."

But even though the heart isn't permanently damaged, mortality rates due to takotsubo syndrome are comparable to those of a heart attack, Merz notes—about 4-5 percent of patients die from the attack, and 20 percent within the next five years. "It's as bad as a heart attack," Merz says—only it's much less known, even to doctors. The condition affects only about 1 percent of people, and there are around 15,000 new cases annually. It's diagnosed using a cardiac ventriculogram, an imaging test that allows doctors to see how the heart pumps blood.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes Takotsubo syndrome, but it usually occurs after extreme emotional or physical stress. Doctors think it's triggered by a so-called catecholamine storm, a phenomenon in which the body releases too much catecholamines—hormones involved in the fight-or-flight response. Evolutionarily, when early humans lived in savannas or forests and had to either fight off predators or flee from them, these hormones gave our ancestors the needed strength and stamina to take either action. Released by nerve endings and by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys, these hormones still flood our bodies in moments of stress, but an overabundance of them could sometimes be damaging.

Elaine Kamil

A study by scientists at Harvard Medical School linked increased risk of takotsubo to higher activity in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for emotions that's involved in responses to stress. The scientists believe that chronic stress makes people more susceptible to the syndrome. Notably, one small study suggested that the number of Takotsubo cases increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are no specific drugs to treat takotsubo, so doctors rely on supportive therapies, which include medications typically used for high blood pressure and heart failure. In most cases, the heart returns to its normal shape within a few weeks. "It's a spontaneous recovery—the catecholamine storm is resolved, the injury trigger is removed and the heart heals itself because our bodies have an amazing healing capacity," Merz says. It also helps that tissues remain intact. 'The heart cells don't die, they just aren't functioning properly for some time."

That's the good news. The bad news is that takotsubo is likely to strike again—in 5-20 percent of patients the condition comes back, sometimes more severe than before.

That's exactly what happened to Kamil. After getting her diagnosis in 2013, she realized that she actually had a previous takotsubo episode. In 2010, she experienced similar symptoms after her son died. "The night after he died, I was having severe chest pain at night, but I was too overwhelmed with grief to do anything about it," she recalls. After a while, the pain subsided and didn't return until three years later.

For weeks after her second attack, she felt exhausted, listless and anxious. "You lose confidence in your body," she says. "You have these little twinges on your chest, or if you start having arrhythmia, and you wonder if this is another episode coming up. It's really unnerving because you don't know how to read these cues." And that's very typical, Merz says. Even when the heart muscle appears to recover, patients don't return to normal right away. They have shortens of breath, they can't exercise, and they stay anxious and worried for a while.

Women over the age of 50 are diagnosed with takotsubo more often than other demographics. However, it happens in men too, although it typically strikes after physical stress, such as a triathlon or an exhausting day of cycling. Young people can also get takotsubo. Older patients are hospitalized more often, but younger people tend to have more severe complications. It could be because an older person may go for a jog while younger one may run a marathon, which would take a stronger toll on the body of a person who's predisposed to the condition.

Notably, the emotional stressors don't always have to be negative—the heart muscle can get out of shape from good emotions, too. "There have been case reports of takotsubo at weddings," Merz says. Moreover, one out of three or four takotsubo patients experience no apparent stress, she adds. "So it could be that it's not so much the catecholamine storm itself, but the body's reaction to it—the physiological reaction deeply embedded into out physiology," she explains.

Merz and her team are working to understand what makes people predisposed to takotsubo. They think a person's genetics play a role, but they haven't yet pinpointed genes that seem to be responsible. Genes code for proteins, which affect how the body metabolizes various compounds, which, in turn, affect the body's response to stress. Pinning down the protein involved in takotsubo susceptibility would allow doctors to develop screening tests and identify those prone to severe repeating attacks. It will also help develop medications that can either prevent it or treat it better than just waiting for the body to heal itself.

Researchers at the Imperial College London found that elevated levels of certain types of microRNAs—molecules involved in protein production—increase the chances of developing takotsubo.

In one study, researchers tried treating takotsubo in mice with a drug called suberanilohydroxamic acid, or SAHA, typically used for cancer treatment. The drug improved cardiac health and reversed the broken heart in rodents. It remains to be seen if the drug would have a similar effect on humans. But identifying a drug that shows promise is progress, Merz says. "I'm glad that there's research in this area."

This article was originally published by Leaps.org on July 28, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

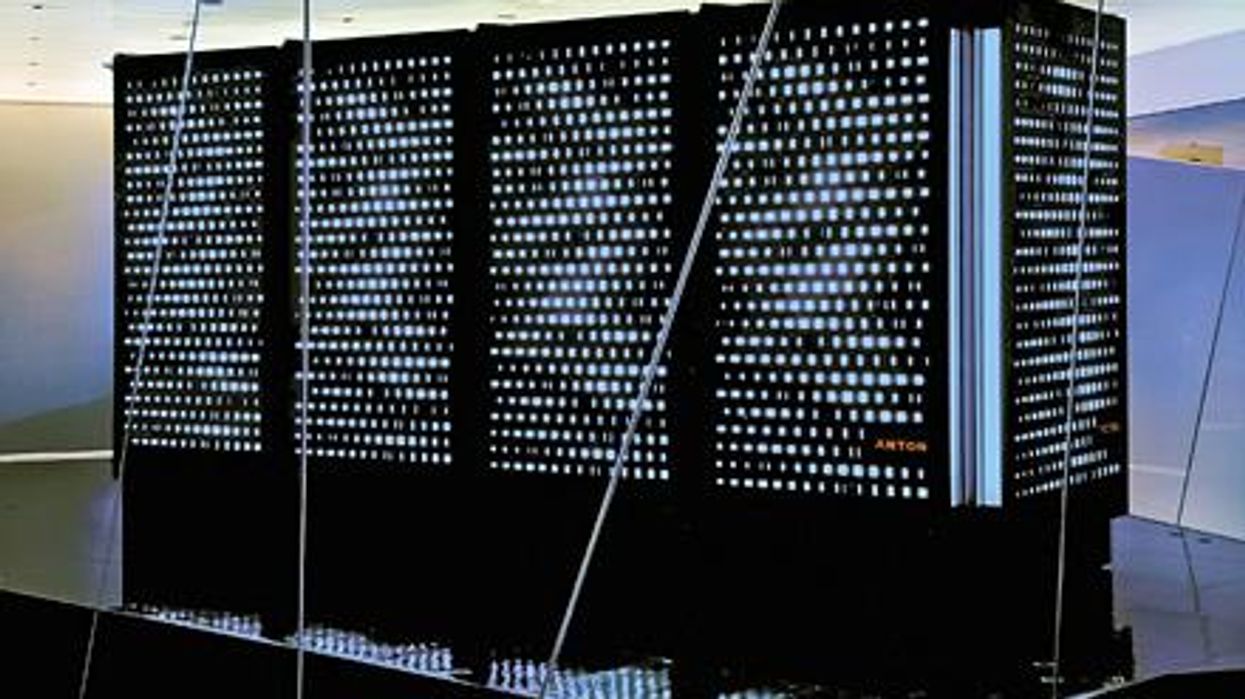

Did Anton the AI find a new treatment for a deadly cancer?

Researchers used a supercomputer to learn about the subtle movement of a cancer-causing molecule, and then they found the precise drug that can recognize that motion.

Bile duct cancer is a rare and aggressive form of cancer that is often difficult to diagnose. Patients with advanced forms of the disease have an average life expectancy of less than two years.

Many patients who get cancer in their bile ducts – the tubes that carry digestive fluid from the liver to the small intestine – have mutations in the protein FGFR2, which leads cells to grow uncontrollably. One treatment option is chemotherapy, but it’s toxic to both cancer cells and healthy cells, failing to distinguish between the two. Increasingly, cancer researchers are focusing on biomarker directed therapy, or making drugs that target a particular molecule that causes the disease – FGFR2, in the case of bile duct cancer.

A problem is that in targeting FGFR2, these drugs inadvertently inhibit the FGFR1 protein, which looks almost identical. This causes elevated phosphate levels, which is a sign of kidney damage, so doses are often limited to prevent complications.

In recent years, though, a company called Relay has taken a unique approach to picking out FGFR2, using a powerful supercomputer to simulate how proteins move and change shape. The team, leveraging this AI capability, discovered that FGFR2 and FGFR1 move differently, which enabled them to create a more precise drug.

Preliminary studies have shown robust activity of this drug, called RLY-4008, in FGFR2 altered tumors, especially in bile duct cancer. The drug did not inhibit FGFR1 or cause significant side effects. “RLY-4008 is a prime example of a precision oncology therapeutic with its highly selective and potent targeting of FGFR2 genetic alterations and resistance mutations,” says Lipika Goyal, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is a principal investigator of Relay’s phase 1-2 clinical trial.

Boosts from AI and a billionaire

Traditional drug design has been very much a case of trial and error, as scientists investigate many molecules to see which ones bind to the intended target and bind less to other targets.

“It’s being done almost blindly, without really being guided by structure, so it fails very often,” says Olivier Elemento, associate director of the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Cornell. “The issue is that they are not sampling enough molecules to cover some of the chemical space that would be specific to the target of interest and not specific to others.”

Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

Some scientists have tried to use X-rays of crystallized proteins to look at the structure of proteins and design better drugs. But they have failed to account for an important factor: proteins are moving and constantly folding into different shapes.

David Shaw, a hedge fund billionaire, wanted to help improve drug discovery and understood that a key obstacle was that computer models of molecular dynamics were limited; they simulated motion for less than 10 millionths of a second.

In 2001, Shaw set up his own research facility, D.E. Shaw Research, to create a supercomputer that would be specifically designed to simulate protein motion. Seven years later, he succeeded in firing up a supercomputer that can now conduct high speed simulations roughly 100 times faster than others. Called Anton, it has special computer chips to enable this speed, and its software is powered by AI to conduct many simulations.

After creating the supercomputer, Shaw teamed up with leading scientists who were interested in molecular motion, and they founded Relay Therapeutics.

Elemento believes that Relay’s approach is highly beneficial in designing a better drug for bile duct cancer. “Relay Therapeutics has a cutting-edge approach for molecular dynamics that I don’t believe any other companies have, at least not as advanced.” Relay’s unique hardware and software allow simulations that could never be achieved through traditional experiments, Elemento says.

How it works

Relay used both experimental and computational approaches to design RLY-4008. The team started out by taking X-rays of crystallized versions of both their intended target, FGFR2, and the almost identical FGFR1. This enabled them to get a 3D snapshot of each of their structures. They then fed the X-rays into the Anton supercomputer to simulate how the proteins were likely to move.

Anton’s simulations showed that the FGFR1 protein had a flap that moved more frequently than FGFR2. Based on this distinct motion, the team tried to design a compound that would recognize this flap shifting around and bind to FGFR2 while steering away from its more active lookalike.

For that, they went back Anton, using the supercomputer to simulate the behavior of thousands of potential molecules for over a year, looking at what made a particular molecule selective to the target versus another molecule that wasn’t. These insights led them to determine the best compounds to make and test in the lab and, ultimately, they found that RLY-4008 was the most effective.

Promising results so far

Relay began phase 1-2 trials in 2020 and will continue until 2024. Preliminary results showed that, in the 17 patients taking a 70 mg dose of RLY-4008, the drug worked to shrink tumors in 88 percent of patients. This was a significant increase compared to other FGFR inhibitors. For instance, Futibatinib, which recently got FDA approval, had a response rate of only 42 percent.

Across all dose levels, RLY-4008 shrank tumors by 63 percent in 38 patients. In more good news, the drug didn’t elevate their phosphate levels, which suggests that it could be taken without increasing patients’ risk for kidney disease.

“Objectively, this is pretty remarkable,” says Elemento. “In a small patient study, you have a molecule that is able to shrink tumors in such a high fraction of patients. It is unusual to see such good results in a phase 1-2 trial.”

A simulated future

The research team is continuing to use molecular dynamic simulations to develop other new drug, such as one that is being studied in patients with solid tumors and breast cancer.

As for their bile duct cancer drug, RLY-4008, Relay plans by 2024 to have tested it in around 440 patients. “The mature results of the phase 1-2 trial are highly anticipated,” says Goyal, the principal investigator of the trial.

Sameek Roychowdhury, an oncologist and associate professor of internal medicine at Ohio State University, highlights the need for caution. “This has early signs of benefit, but we will look forward to seeing longer term results for benefit and side effect profiles. We need to think a few more steps ahead - these treatments are like the ’Whack-a-Mole game’ where cancer finds a way to become resistant to each subsequent drug.”

“I think the issue is going to be how durable are the responses to the drug and what are the mechanisms of resistance,” says Raymond Wadlow, an oncologist at the Inova Medical Group who specializes in gastrointestinal and haematological cancer. “But the results look promising. It is a much more selective inhibitor of the FGFR protein and less toxic. It’s been an exciting development.”