Can You Trust Your Gut for Food Advice?

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Which foods are actually healthy for your individual gut microbiome? Several companies are offering personalized dietary guidance based on your test results, but their answers in one experiment turned up with some conflicting advice.

I recently got on the scale to weigh myself, thinking I've got to eat better. With so many trendy diets today claiming to improve health, from Keto to Paleo to Whole30, it can be confusing to figure out what we should and shouldn't eat for optimal nutrition.

A number of companies are now selling the concept of "personalized" nutrition based on the genetic makeup of your individual gut bugs.

My next thought was: I've got to lose a few pounds.

Consider a weird factoid: In addition to my fat, skin, bone and muscle, I'm carrying around two or three pounds of straight-up bacteria. Like you, I am the host to trillions of micro-organisms that live in my gut and are collectively known as my microbiome. An explosion of research has occurred in the last decade to try to understand exactly how these microbial populations, which are unique to each of us, may influence our overall health and potentially even our brains and behavior.

Lots of mysteries still remain, but it is established that these "bugs" are crucial to keeping our body running smoothly, performing functions like stimulating the immune system, synthesizing important vitamins, and aiding digestion. The field of microbiome science is evolving rapidly, and a number of companies are now selling the concept of "personalized" nutrition based on the genetic makeup of your individual gut bugs. The two leading players are Viome and DayTwo, but the landscape includes the newly launched startup Onegevity Health and others like Thryve, which offers customized probiotic supplements in addition to dietary recommendations.

The idea has immediate appeal – if science could tell you exactly what to make for lunch and what to avoid, you could forget about the fad diets and go with your own bespoke food pyramid. Wondering if the promise might be too good to be true, I decided to perform my own experiment.

Last fall, I sent the identical fecal sample to both Viome (I paid $425, but the price has since dropped to $299) and DayTwo ($349). A couple of months later, both reports finally arrived, and I eagerly opened each app to compare their recommendations.

First, I examined my results from Viome, which was founded in 2016 in Cupertino, Calif., and declares without irony on its website that "conflicting food advice is now obsolete."

I learned I have "average" metabolic fitness and "average" inflammatory activity in my gut, which are scores that the company defines based on a proprietary algorithm. But I have "low" microbial richness, with only 62 active species of bacteria identified in my sample, compared with the mean of 157 in their test population. I also received a list of the specific species in my gut, with names like Lactococcus and Romboutsia.

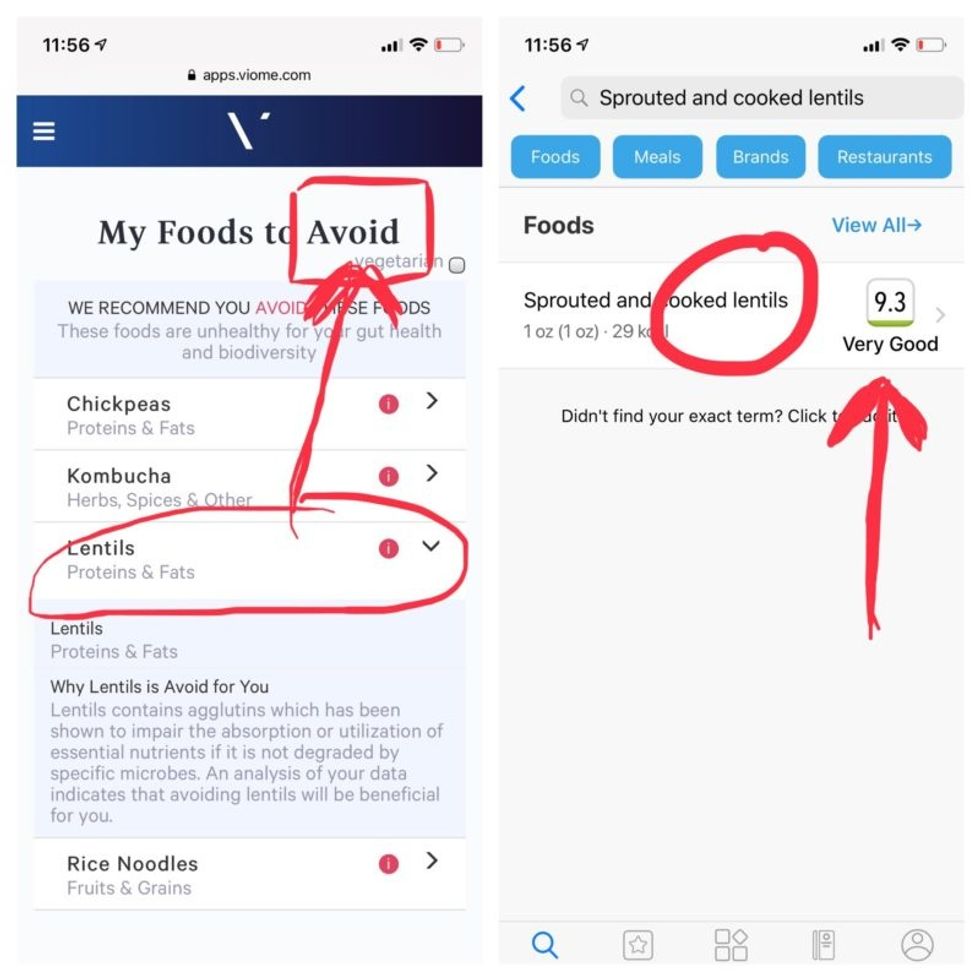

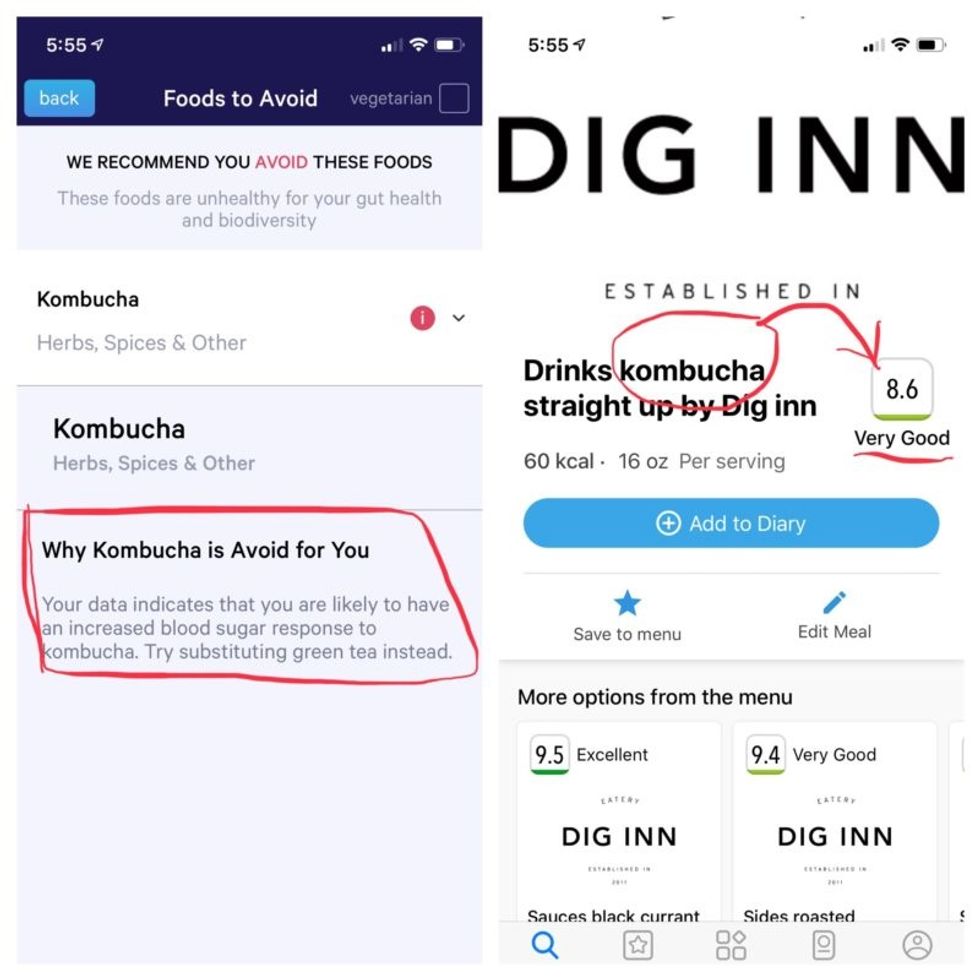

But none of it meant anything to me without actionable food advice, so I clicked through to the Recommendations page and found a list of My Superfoods (cranberry, garlic, kale, salmon, turmeric, watermelon, and bone broth) and My Foods to Avoid (chickpeas, kombucha, lentils, and rice noodles). There was also a searchable database of many foods that had been categorized for me, like "bell pepper; minimize" and "beef; enjoy."

"I just don't think sufficient data is yet available to make reliable personalized dietary recommendations based on one's microbiome."

Next, I looked at my results from DayTwo, which was founded in 2015 from research out of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and whose pitch to consumers is, "Blood sugar made easy. The algorithm diet personalized to you."

This app had some notable differences. There was no result about my metabolic fitness, microbial richness, or list of the species in my sample. There was also no list of superfoods or foods to avoid. Instead, the app encouraged me to build a meal by searching for foods in their database and combining them in beneficial ways for my blood sugar. Two slices of whole wheat bread received a score of 2.7 out of 10 ("Avoid"), but if combined with one cup of large curd cottage cheese, the score improved to 6.8 ("Limit"), and if I added two hard-boiled eggs, the score went up to 7.5 ("Good").

Perusing my list of foods with "Excellent" scores, I noticed some troubling conflicts with the other app. Lentils, which had been a no-no according to Viome, received high marks from DayTwo. Ditto for Kombucha. My purported superfood of cranberry received low marks. Almonds got an almost perfect score (9.7) while Viome told me to minimize them. I found similarly contradictory advice for foods I regularly eat, including navel oranges, peanuts, pork, and beets.

Contradictory dietary guidance that Kira Peikoff received from Viome (left) and DayTwo from an identical sample.

To be sure, there was some overlap. Both apps agreed on rice noodles (bad), chickpeas (bad), honey (bad), carrots (good), and avocado (good), among other foods.

But still, I was left scratching my head. Which set of recommendations should I trust, if either? And what did my results mean for the accuracy of this nascent field?

I called a couple of experts to find out.

"I have worked on the microbiome and nutrition for the last 20 years and I would be absolutely incapable of finding you evidence in the scientific literature that lentils have a detrimental effect based on the microbiome," said Dr. Jens Walter, an Associate Professor and chair for Nutrition, Microbes, and Gastrointestinal Health at the University of Alberta. "I just don't think sufficient data is yet available to make reliable personalized dietary recommendations based on one's microbiome. And even if they would have proprietary algorithms, at least one of them is not doing it right."

There is definite potential for personalized nutrition based on the microbiome, he said, but first, predictive models must be built and standardized, then linked to clinical endpoints, and tested in a large sample of healthy volunteers in order to enable extrapolations for the general population.

"It is mindboggling what you would need to do to make this work," he observed. "There are probably hundreds of relevant dietary compounds, then the microbiome has at least a hundred relevant species with a hundred or more relevant genes each, then you'd have to put all this together with relevant clinical outcomes. And there's a hundred-fold variation in that information between individuals."

However, Walter did acknowledge that the companies might be basing their algorithms on proprietary data that could potentially connect all the dots. I reached out to them to find out.

Amir Golan, the Chief Commercial Officer of DayTwo, told me, "It's important to emphasize this is a prediction, as the microbiome field is in a very early stage of research." But he added, "I believe we are the only company that has very solid science published in top journals and we can bring very actionable evidence and benefit to our uses."

He was referring to pioneering work out of the Weizmann Institute that was published in 2015 in the journal Cell, which logged the glycemic responses of 800 people in response to nearly 50,000 meals; adding information about the subjects' microbiomes enabled more accurate glycemic response predictions. Since then, Golan said, additional trials have been conducted, most recently with the Mayo Clinic, to duplicate the results, and other studies are ongoing whose results have not yet been published.

He also pointed out that the microbiome was merely one component that goes into building a client's profile, in addition to medical records, including blood glucose levels. (I provided my HbA1c levels, a measure of average blood sugar over the previous several months.)

"We are not saying we want to improve your gut microbiome. We provide a dynamic tool to help guide what you should eat to control your blood sugar and think about combinations," he said. "If you eat one thing, or with another, it will affect you in a different way."

Viome acknowledged that the two companies are taking very different approaches.

"DayTwo is primarily focused on the glycemic response," Naveen Jain, the CEO, told me. "If you can only eat butter for rest of your life, you will have no glycemic response but will probably die of a heart attack." He laughed. "Whereas we came from very different angle – what is happening inside the gut at a microbial level? When you eat food like spinach, how will that be metabolized in the gut? Will it produce the nutrients you need or cause inflammation?"

He said his team studied 1000 people who were on continuous glucose monitoring and fed them 45,000 meals, then built a proprietary data prediction model, looking at which microbes existed and how they actively broke down the food.

Jain pointed out that DayTwo sequences the DNA of the microbes, while Viome sequences the RNA – the active expression of DNA. That difference, in his opinion, is key to making accurate predictions.

"DNA is extremely stable, so when you eat any food and measure the DNA [in a fecal sample], you get all these false positives--you get DNA from plant food and meat, and you have no idea if those organisms are dead and simply transient, or actually exist. With RNA, you see what is actually alive in the gut."

More contradictory food advice from Viome (left) and DayTwo.

Note that controversy exists over how it is possible with a fecal sample to effectively measure RNA, which degrades within minutes, though Jain said that his company has the technology to keep RNA stable for fourteen days.

Viome's approach, Jain maintains, is 90 percent accurate, based on as-yet unpublished data; a patent was filed just last week. DayTwo's approach is 66 percent accurate according to the latest published research.

Natasha Haskey, a registered dietician and doctoral student conducting research in the field of microbiome science and nutrition, is skeptical of both companies. "We can make broad statements, like eat more fruits and vegetables and fiber, but when it comes to specific foods, the science is just not there yet," she said. "I think there is a future, and we will be doing that someday, but not yet. Maybe we will be closer in ten years."

Professor Walter wholeheartedly agrees with Haskey, and suggested that if people want to eat a gut-healthy diet, they should focus on beneficial oils, fruits and vegetables, fish, a variety of whole grains, poultry and beans, and limit red meat and cheese, as well as avoid processed meats.

"These services are far over the tips of their science skis," Arthur Caplan, the founding head of New York University's Division of Medical Ethics, said in an email. "We simply don't know enough about the gut microbiome, its fluctuations and variability from person to person to support general [direct-to-consumer] testing. This is simply premature. We need standards for accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity, plus mandatory competent counseling for all such testing. They don't exist. Neither should DTC testing—yet."

Meanwhile, it's time for lunch. I close out my Viome and DayTwo apps and head to the kitchen to prepare a peanut butter sandwich. My gut tells me I'll be just fine.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

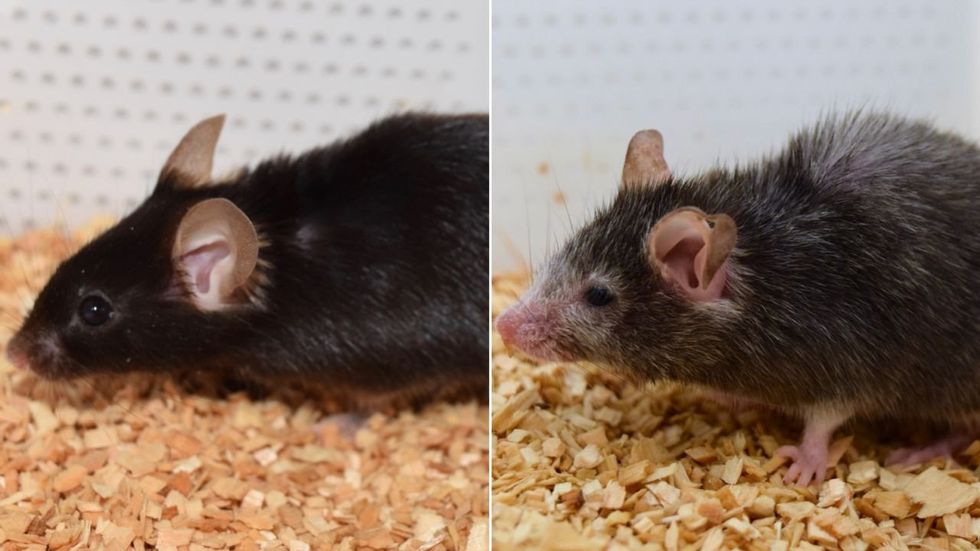

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School