Can You Trust Your Gut for Food Advice?

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Which foods are actually healthy for your individual gut microbiome? Several companies are offering personalized dietary guidance based on your test results, but their answers in one experiment turned up with some conflicting advice.

I recently got on the scale to weigh myself, thinking I've got to eat better. With so many trendy diets today claiming to improve health, from Keto to Paleo to Whole30, it can be confusing to figure out what we should and shouldn't eat for optimal nutrition.

A number of companies are now selling the concept of "personalized" nutrition based on the genetic makeup of your individual gut bugs.

My next thought was: I've got to lose a few pounds.

Consider a weird factoid: In addition to my fat, skin, bone and muscle, I'm carrying around two or three pounds of straight-up bacteria. Like you, I am the host to trillions of micro-organisms that live in my gut and are collectively known as my microbiome. An explosion of research has occurred in the last decade to try to understand exactly how these microbial populations, which are unique to each of us, may influence our overall health and potentially even our brains and behavior.

Lots of mysteries still remain, but it is established that these "bugs" are crucial to keeping our body running smoothly, performing functions like stimulating the immune system, synthesizing important vitamins, and aiding digestion. The field of microbiome science is evolving rapidly, and a number of companies are now selling the concept of "personalized" nutrition based on the genetic makeup of your individual gut bugs. The two leading players are Viome and DayTwo, but the landscape includes the newly launched startup Onegevity Health and others like Thryve, which offers customized probiotic supplements in addition to dietary recommendations.

The idea has immediate appeal – if science could tell you exactly what to make for lunch and what to avoid, you could forget about the fad diets and go with your own bespoke food pyramid. Wondering if the promise might be too good to be true, I decided to perform my own experiment.

Last fall, I sent the identical fecal sample to both Viome (I paid $425, but the price has since dropped to $299) and DayTwo ($349). A couple of months later, both reports finally arrived, and I eagerly opened each app to compare their recommendations.

First, I examined my results from Viome, which was founded in 2016 in Cupertino, Calif., and declares without irony on its website that "conflicting food advice is now obsolete."

I learned I have "average" metabolic fitness and "average" inflammatory activity in my gut, which are scores that the company defines based on a proprietary algorithm. But I have "low" microbial richness, with only 62 active species of bacteria identified in my sample, compared with the mean of 157 in their test population. I also received a list of the specific species in my gut, with names like Lactococcus and Romboutsia.

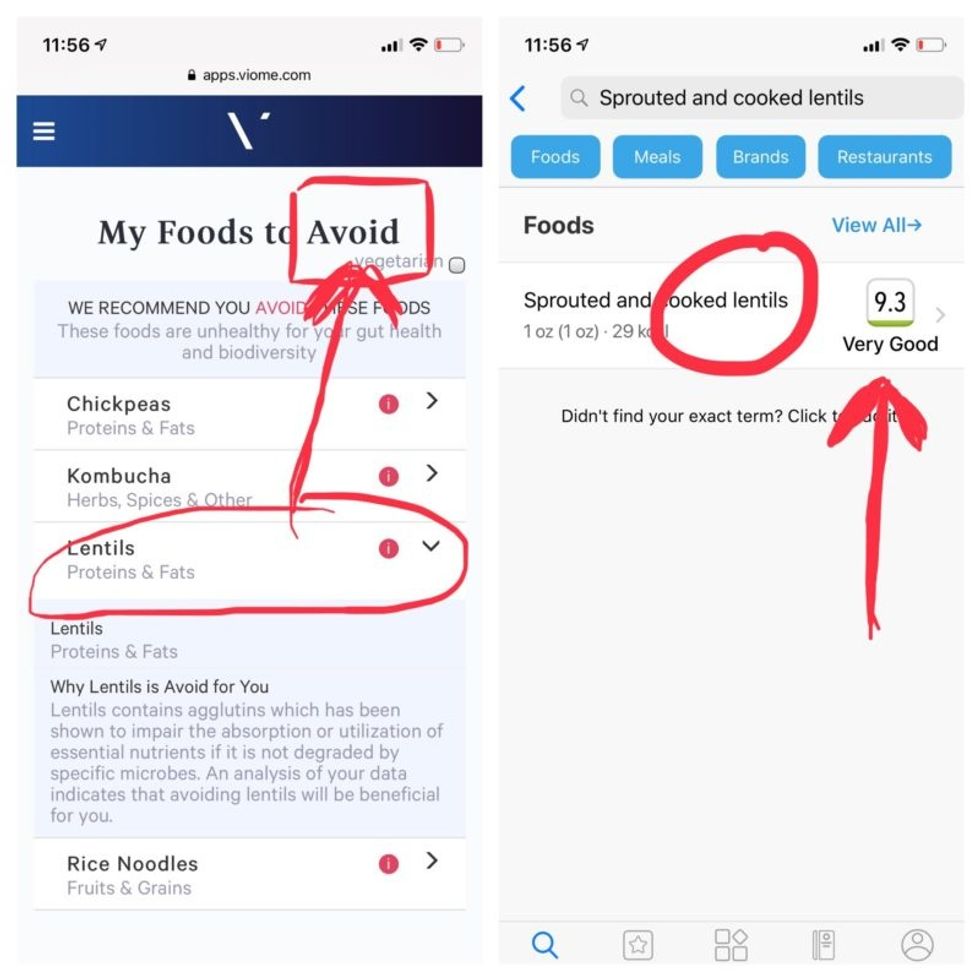

But none of it meant anything to me without actionable food advice, so I clicked through to the Recommendations page and found a list of My Superfoods (cranberry, garlic, kale, salmon, turmeric, watermelon, and bone broth) and My Foods to Avoid (chickpeas, kombucha, lentils, and rice noodles). There was also a searchable database of many foods that had been categorized for me, like "bell pepper; minimize" and "beef; enjoy."

"I just don't think sufficient data is yet available to make reliable personalized dietary recommendations based on one's microbiome."

Next, I looked at my results from DayTwo, which was founded in 2015 from research out of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, and whose pitch to consumers is, "Blood sugar made easy. The algorithm diet personalized to you."

This app had some notable differences. There was no result about my metabolic fitness, microbial richness, or list of the species in my sample. There was also no list of superfoods or foods to avoid. Instead, the app encouraged me to build a meal by searching for foods in their database and combining them in beneficial ways for my blood sugar. Two slices of whole wheat bread received a score of 2.7 out of 10 ("Avoid"), but if combined with one cup of large curd cottage cheese, the score improved to 6.8 ("Limit"), and if I added two hard-boiled eggs, the score went up to 7.5 ("Good").

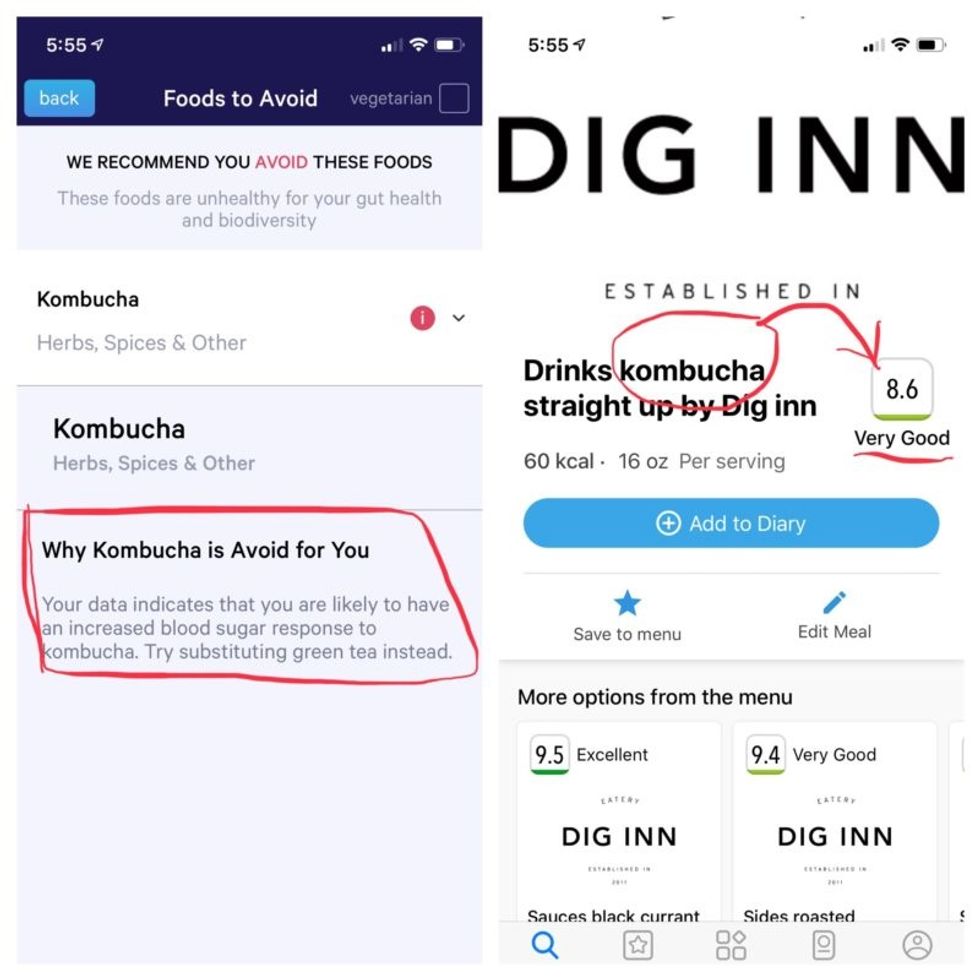

Perusing my list of foods with "Excellent" scores, I noticed some troubling conflicts with the other app. Lentils, which had been a no-no according to Viome, received high marks from DayTwo. Ditto for Kombucha. My purported superfood of cranberry received low marks. Almonds got an almost perfect score (9.7) while Viome told me to minimize them. I found similarly contradictory advice for foods I regularly eat, including navel oranges, peanuts, pork, and beets.

Contradictory dietary guidance that Kira Peikoff received from Viome (left) and DayTwo from an identical sample.

To be sure, there was some overlap. Both apps agreed on rice noodles (bad), chickpeas (bad), honey (bad), carrots (good), and avocado (good), among other foods.

But still, I was left scratching my head. Which set of recommendations should I trust, if either? And what did my results mean for the accuracy of this nascent field?

I called a couple of experts to find out.

"I have worked on the microbiome and nutrition for the last 20 years and I would be absolutely incapable of finding you evidence in the scientific literature that lentils have a detrimental effect based on the microbiome," said Dr. Jens Walter, an Associate Professor and chair for Nutrition, Microbes, and Gastrointestinal Health at the University of Alberta. "I just don't think sufficient data is yet available to make reliable personalized dietary recommendations based on one's microbiome. And even if they would have proprietary algorithms, at least one of them is not doing it right."

There is definite potential for personalized nutrition based on the microbiome, he said, but first, predictive models must be built and standardized, then linked to clinical endpoints, and tested in a large sample of healthy volunteers in order to enable extrapolations for the general population.

"It is mindboggling what you would need to do to make this work," he observed. "There are probably hundreds of relevant dietary compounds, then the microbiome has at least a hundred relevant species with a hundred or more relevant genes each, then you'd have to put all this together with relevant clinical outcomes. And there's a hundred-fold variation in that information between individuals."

However, Walter did acknowledge that the companies might be basing their algorithms on proprietary data that could potentially connect all the dots. I reached out to them to find out.

Amir Golan, the Chief Commercial Officer of DayTwo, told me, "It's important to emphasize this is a prediction, as the microbiome field is in a very early stage of research." But he added, "I believe we are the only company that has very solid science published in top journals and we can bring very actionable evidence and benefit to our uses."

He was referring to pioneering work out of the Weizmann Institute that was published in 2015 in the journal Cell, which logged the glycemic responses of 800 people in response to nearly 50,000 meals; adding information about the subjects' microbiomes enabled more accurate glycemic response predictions. Since then, Golan said, additional trials have been conducted, most recently with the Mayo Clinic, to duplicate the results, and other studies are ongoing whose results have not yet been published.

He also pointed out that the microbiome was merely one component that goes into building a client's profile, in addition to medical records, including blood glucose levels. (I provided my HbA1c levels, a measure of average blood sugar over the previous several months.)

"We are not saying we want to improve your gut microbiome. We provide a dynamic tool to help guide what you should eat to control your blood sugar and think about combinations," he said. "If you eat one thing, or with another, it will affect you in a different way."

Viome acknowledged that the two companies are taking very different approaches.

"DayTwo is primarily focused on the glycemic response," Naveen Jain, the CEO, told me. "If you can only eat butter for rest of your life, you will have no glycemic response but will probably die of a heart attack." He laughed. "Whereas we came from very different angle – what is happening inside the gut at a microbial level? When you eat food like spinach, how will that be metabolized in the gut? Will it produce the nutrients you need or cause inflammation?"

He said his team studied 1000 people who were on continuous glucose monitoring and fed them 45,000 meals, then built a proprietary data prediction model, looking at which microbes existed and how they actively broke down the food.

Jain pointed out that DayTwo sequences the DNA of the microbes, while Viome sequences the RNA – the active expression of DNA. That difference, in his opinion, is key to making accurate predictions.

"DNA is extremely stable, so when you eat any food and measure the DNA [in a fecal sample], you get all these false positives--you get DNA from plant food and meat, and you have no idea if those organisms are dead and simply transient, or actually exist. With RNA, you see what is actually alive in the gut."

More contradictory food advice from Viome (left) and DayTwo.

Note that controversy exists over how it is possible with a fecal sample to effectively measure RNA, which degrades within minutes, though Jain said that his company has the technology to keep RNA stable for fourteen days.

Viome's approach, Jain maintains, is 90 percent accurate, based on as-yet unpublished data; a patent was filed just last week. DayTwo's approach is 66 percent accurate according to the latest published research.

Natasha Haskey, a registered dietician and doctoral student conducting research in the field of microbiome science and nutrition, is skeptical of both companies. "We can make broad statements, like eat more fruits and vegetables and fiber, but when it comes to specific foods, the science is just not there yet," she said. "I think there is a future, and we will be doing that someday, but not yet. Maybe we will be closer in ten years."

Professor Walter wholeheartedly agrees with Haskey, and suggested that if people want to eat a gut-healthy diet, they should focus on beneficial oils, fruits and vegetables, fish, a variety of whole grains, poultry and beans, and limit red meat and cheese, as well as avoid processed meats.

"These services are far over the tips of their science skis," Arthur Caplan, the founding head of New York University's Division of Medical Ethics, said in an email. "We simply don't know enough about the gut microbiome, its fluctuations and variability from person to person to support general [direct-to-consumer] testing. This is simply premature. We need standards for accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity, plus mandatory competent counseling for all such testing. They don't exist. Neither should DTC testing—yet."

Meanwhile, it's time for lunch. I close out my Viome and DayTwo apps and head to the kitchen to prepare a peanut butter sandwich. My gut tells me I'll be just fine.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

The Friday Five: Sugar could help catch cancer early

In this week's Friday Five, catching cancer early could depend on sugar, how to boost memory in a flash, a tiny sandwich cake could help the heart, and meet the top banana in the fight against Covid.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Catching cancer early could depend on sugar

- How to boost memory in a flash

- This is your brain on books

- A tiny sandwich cake could help the heart

- Meet the top banana for fighting Covid variants

A surprising weapon in the fight against food poisoning

Phages, which are harmless viruses that destroy specific bacteria, are becoming useful tools to protect our food supply.

Every year, one in seven people in America comes down with a foodborne illness, typically caused by a bacterial pathogen, including E.Coli, listeria, salmonella, or campylobacter. That adds up to 48 million people, of which 120,000 are hospitalized and 3000 die, according to the Centers for Disease Control. And the variety of foods that can be contaminated with bacterial pathogens is growing too. In the 20th century, E.Coli and listeria lurked primarily within meat. Now they find their way into lettuce, spinach, and other leafy greens, causing periodic consumer scares and product recalls. Onions are the most recent suspected culprit of a nationwide salmonella outbreak.

Some of these incidents are almost inevitable because of how Mother Nature works, explains Divya Jaroni, associate professor of animal and food sciences at Oklahoma State University. These common foodborne pathogens come from the cattle's intestines when the animals shed them in their manure—and then they get washed into rivers and lakes, especially in heavy rains. When this water is later used to irrigate produce farms, the bugs end up on salad greens. Plus, many small farms do both—herd cattle and grow produce.

"Unfortunately for us, these pathogens are part of the microflora of the cows' intestinal tract," Jaroni says. "Some farmers may have an acre or two of cattle pastures, and an acre of a produce farm nearby, so it's easy for this water to contaminate the crops."

Food producers and packagers fight bacteria by potent chemicals, with chlorine being the go-to disinfectant. Cattle carcasses, for example, are typically washed by chlorine solutions as the animals' intestines are removed. Leafy greens are bathed in water with added chlorine solutions. However, because the same "bath" can be used for multiple veggie batches and chlorine evaporates over time, the later rounds may not kill all of the bacteria, sparing some. The natural and organic producers avoid chlorine, substituting it with lactic acid, a more holistic sanitizer, but even with all these efforts, some pathogens survive, sickening consumers and causing food recalls. As we farm more animals and grow more produce, while also striving to use fewer chemicals and more organic growing methods, it will be harder to control bacteria's spread.

"It took us a long time to convince the FDA phages were safe and efficient alternatives. But we had worked with them to gather all the data they needed, and the FDA was very supportive in the end."

Luckily, bacteria have their own killers. Called bacteriophages, or phages for short, they are viruses that prey on bacteria only. Under the electron microscope, they look like fantasy spaceships, with oblong bodies, spider-like legs and long tails. Much smaller than a bacterium, phages pierce the microbes' cells with their tails, sneak in and begin multiplying inside, eventually bursting the microbes open—and then proceed to infect more of them.

The best part is that these phages are harmless to humans. Moreover, recent research finds that millions of phages dwell on us and in us—in our nose, throat, skin and gut, protecting us from bacterial infections as part of our healthy microbiome. A recent study suggested that we absorb about 30 billion phages into our bodies on a daily basis. Now, ingeniously, they are starting to be deployed as anti-microbial agents in the food industry.

A Maryland-based phage research company called Intralytix is doing just that. Founded by Alexander Sulakvelidze, a microbiologist and epidemiologist who came to the United States from Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, Intralytix makes and sells five different FDA-approved phage cocktails that work against some of the most notorious food pathogens: ListShield for Listeria, SalmoFresh for Salmonella, ShigaShield for Shigella, another foodborne bug, and EcoShield for E.coli, including the infamous strain that caused the Jack in the Box outbreak in 1993 that killed four children and sickened 732 people across four states. Last year, the FDA granted its approval to yet another Intralytix phage for managing Campylobacter contamination, named CampyShield. "We call it safety by nature," Sulakvelidze says.

Intralytix grows phages inside massive 1500-liter fermenters, feeding them bacterial "fodder."

Photo credit: Living Radiant Photography

Phage preparations are relatively straightforward to make. In nature, phages thrive in any body of water where bacteria live too, including rivers, lakes and bays. "I can dip a bucket into the Chesapeake Bay, and it will be full of all kinds of phages," Sulakvelidze says. "Sewage is another great place to look for specific phages of interest, because it's teeming with all sorts of bacteria—and therefore the viruses that prey on them."

In lab settings, Intralytix grows phages inside massive 1500-liter fermenters, feeding them bacterial "fodder." Once phages multiply enough, they are harvested, dispensed into containers and shipped to food producers who have adopted this disinfecting practice into their preparation process. Typically, it's done by computer-controlled sprayer systems that disperse mist-like phage preparations onto the food.

Unlike chemicals like chlorine or antibiotics, which kill a wide spectrum of bacteria, phages are more specialized, each feeding on specific microbial species. A phage that targets salmonella will not prey on listeria and vice versa. So food producers may sometimes use a combo of different phage preparations. Intralytix is continuously researching and testing new phages. With a contract from the National Institutes of Health, Intralytix is expanding its automated high-throughput robot that tests which phages work best against which bacteria, speeding up the development of the new phage cocktails.

Phages have other "talents." In her recent study, Jaroni found that phages have the ability to destroy bacterial biofilms—colonies of microorganisms that tend to grow on surfaces of the food processing equipment, surrounding themselves with protective coating that even very harsh chemicals can't crack.

"Phages are very clever," Jaroni says. "They produce enzymes that target the biofilms, and once they break through, they can reach the bacteria."

Convincing the FDA that phages were safe to use on food products was no easy feat, Sulakvelidze says. In his home country of Georgia, phages have been used as antimicrobial remedies for over a century, but the FDA was leery of using viruses as food safety agents. "It took us a long time to convince the FDA phages were safe and efficient alternatives," Sulakvelidze says. "But we had worked with them to gather all the data they needed, and the FDA was very supportive in the end."

The agency had granted Intralytix its first approval in 2006, and over the past 10 years, the company's sales increased by over 15-fold. "We currently sell to about 40 companies and are in discussions with several other large food producers," Sulakvelidze says. One indicator that the industry now understands and appreciates the science of phages was that his company was ranked as Top Food Safety Provider in 2021 by Food and Beverage Technology Review, he adds. Notably, phage sprays are kosher, halal and organic-certified.

Intralytix's phage cocktails to safeguard food from bacteria are approved for consumers in addition to food producers, but currently the company sells to food producers only. Selling retail requires different packaging like easy-to-use spray bottles and different marketing that would inform people about phages' antimicrobial qualities. But ultimately, giving people the ability to remove pathogens from their food with probiotic phage sprays is the goal, Sulakvelidze says.

It's not the company's only goal. Now Intralytix is going a step further, investigating phages' probiotic and therapeutic abilities. Because phages are highly specialized in the bacteria they target, they can be used to treat infections caused by specific pathogens while leaving the beneficial species of our microbiome intact. In an ongoing clinical trial with Mount Sinai, Intralytix is now investigating a potential phage treatment against a certain type of E. coli for patients with Crohn's disease, and is about to start another clinical trial for treating bacterial dysentery.

"Now that we have proved that phages are safe and effective against foodborne bacteria," Sulakvelidze says, "we are going to demonstrate their potential in therapeutic applications."

This article was first published by Leaps.org on October 27, 2021.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.