Study Shows “Living Drug” Can Provide a Lasting Cure for Cancer

A recent study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania examined how CAR-T therapy helped Doug Olson beat a cancer death sentence for over a decade - and how it could work for more people.

Doug Olson was 49 when he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, a blood cancer that strikes 21,000 Americans annually. Although the disease kills most patients within a decade, Olson’s case progressed more slowly, and courses of mild chemotherapy kept him healthy for 13 years. Then, when he was 62, the medication stopped working. The cancer had mutated, his doctor explained, becoming resistant to standard remedies. Harsher forms of chemo might buy him a few months, but their side effects would be debilitating. It was time to consider the treatment of last resort: a bone-marrow transplant.

Olson, a scientist who developed blood-testing instruments, knew the odds. There was only a 50 percent chance that a transplant would cure him. There was a 20 percent chance that the agonizing procedure—which involves destroying the patient’s marrow with chemo and radiation, then infusing his blood with donated stem cells—would kill him. If he survived, he would face the danger of graft-versus-host disease, in which the donor’s cells attack the recipient’s tissues. To prevent it, he would have to take immunosuppressant drugs, increasing the risk of infections. He could end up with pneumonia if one of his three grandchildren caught a sniffle. “I was being pushed into a corner,” Olson recalls, “with very little room to move.”

Soon afterward, however, his doctor revealed a possible escape route. He and some colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center were starting a clinical trial, he said, and Olson—still mostly symptom-free—might be a good candidate. The experimental treatment, known as CAR-T therapy, would use genetic engineering to turn his T lymphocytes (immune cells that guard against viruses and other pathogens) into a weapon against cancer.

In September 2010, technicians took some of Olson’s T cells to a laboratory, where they were programmed with new molecular marching orders and coaxed to multiply into an army of millions. When they were ready, a nurse inserted a catheter into his neck. At the turn of a valve, his soldiers returned home, ready to do battle.

“I felt like I’d won the lottery,” Olson says. But he was only the second person in the world to receive this “living drug,” as the University of Pennsylvania investigators called it. No one knew how long his remission would last.

Three weeks later, Olson was slammed with a 102-degree fever, nausea, and chills. The treatment had triggered two dangerous complications: cytokine release syndrome, in which immune chemicals inflame the patient’s tissues, and tumor lysis syndrome, in which toxins from dying cancer cells overwhelm the kidneys. But the crisis passed quickly, and the CAR-T cells fought on. A month after the infusion, the doctor delivered astounding news: “We can’t find any cancer in your body.”

“I felt like I’d won the lottery,” Olson says. But he was only the second person in the world to receive this “living drug,” as the University of Pennsylvania investigators called it. No one knew how long his remission would last.

An Unexpected Cure

In February 2022, the same cancer researchers reported a remarkable milestone: the trial’s first two patients had survived for more than a decade. Although Olson’s predecessor—a retired corrections officer named Bill Ludwig—died of COVID-19 complications in early 2021, both men had remained cancer-free. And the modified immune cells continued to patrol their territory, ready to kill suspected tumor cells the moment they arose.

“We can now conclude that CAR-T cells can actually cure patients with leukemia,” University of Pennsylvania immunologist Carl June, who spearheaded the development of the technique, told reporters. “We thought the cells would be gone in a month or two. The fact that they’ve survived 10 years is a major surprise.”

Even before the announcement, it was clear that CAR-T therapy could win a lasting reprieve for many patients with cancers that were once a death sentence. Since the Food and Drug Administration approved June’s version (marketed as Kymriah) in 2017, the agency has greenlighted five more such treatments for various types of leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. “Every single day, I take care of patients who would previously have been told they had no options,” says Rayne Rouce, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at Texas Children’s Cancer Center. “Now we not only have a treatment option for those patients, but one that could potentially be the last therapy for their cancer that they’ll ever have to receive.”

Immunologist Carl June, middle, spearheaded development of the CAR-T therapy that gave patients Bill Ludwig, left, and Doug Olson, right, a lengthy reprieve on their terminal cancer diagnoses.

Penn Medicine

Yet the CAR-T approach doesn’t help everyone. So far, it has only shown success for blood cancers—and for those, the overall remission rate is 30 to 40 percent. “When it works, it works extraordinarily well,” says Olson’s former doctor, David Porter, director of Penn’s blood and bone marrow transplant program. “It’s important to know why it works, but it’s equally important to know why it doesn’t—and how we can fix that.”

The team’s study, published in the journal Nature, offers a wealth of data on what worked for these two patients. It may also hold clues for how to make the therapy effective for more people.

Building a Better T Cell

Carl June didn’t set out to cure cancer, but his serendipitous career path—and a personal tragedy—helped him achieve insights that had eluded other researchers. In 1971, hoping to avoid combat in Vietnam, he applied to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. June showed a knack for biology, so the Navy sent him on to Baylor College of Medicine. He fell in love with immunology during a fellowship researching malaria vaccines in Switzerland. Later, the Navy deployed him to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle to study bone marrow transplantation.

There, June became part of the first research team to learn how to culture T cells efficiently in a lab. After moving on to the National Naval Medical Center in the ’80s, he used that knowledge to combat the newly emerging AIDS epidemic. HIV, the virus that causes the disease, invades T cells and eventually destroys them. June and his post-doc Bruce Levine developed a method to restore patients’ depleted cell populations, using tiny magnetic beads to deliver growth-stimulating proteins. Infused into the body, the new T cells effectively boosted immune function.

In 1999, after leaving the Navy, June joined the University of Pennsylvania. His wife, who’d been diagnosed with ovarian cancer, died two years later, leaving three young children. “I had not known what it was like to be on the other side of the bed,” he recalls. Watching her suffer through grueling but futile chemotherapy, followed by an unsuccessful bone-marrow transplant, he resolved to focus on finding better cancer treatments. He started with leukemia—a family of diseases in which mutant white blood cells proliferate in the marrow.

Cancer is highly skilled at slipping through the immune system’s defenses. T cells, for example, detect pathogens by latching onto them with receptors designed to recognize foreign proteins. Leukemia cells evade detection, in part, by masquerading as normal white blood cells—that is, as part of the immune system itself.

June planned to use a viral vector no one had tried before: HIV.

To June, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells looked like a promising tool for unmasking and destroying the impostors. Developed in the early ’90s, these cells could be programmed to identify a target protein, and to kill any pathogen that displayed it. To do the programming, you spliced together snippets of DNA and inserted them into a disabled virus. Next, you removed some of the patient’s T cells and infected them with the virus, which genetically hijacked its new hosts—instructing them to find and slay the patient’s particular type of cancer cells. When the T cells multiplied, their descendants carried the new genetic code. You then infused those modified cells into the patient, where they went to war against their designated enemy.

Or that’s what happened in theory. Many scientists had tried to develop therapies using CAR-T cells, but none had succeeded. Although the technique worked in lab animals, the cells either died out or lost their potency in humans.

But June had the advantage of his years nurturing T cells for AIDS patients, as well as the technology he’d developed with Levine (who’d followed him to Penn with other team members). He also planned to use a viral vector no one had tried before: HIV, which had evolved to thrive in human T cells and could be altered to avoid causing disease. By the summer of 2010, he was ready to test CAR-T therapy against chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most common form of the disease in adults.

Three patients signed up for the trial, including Doug Olson and Bill Ludwig. A portion of each man’s T cells were reprogrammed to detect a protein found only on B lymphocytes, the type of white blood cells affected by CLL. Their genetic instructions ordered them to destroy any cell carrying the protein, known as CD19, and to multiply whenever they encountered one. This meant the patients would forfeit all their B cells, not just cancerous ones—but regular injections of gamma globulins (a cocktail of antibodies) would make up for the loss.

After being infused with the CAR-T cells, all three men suffered high fevers and potentially life-threatening inflammation, but all pulled through without lasting damage. The third patient experienced a partial remission and survived for eight months. Olson and Ludwig were cured.

Learning What Works

Since those first infusions, researchers have developed reliable ways to prevent or treat the side effects of CAR-T therapy, greatly reducing its risks. They’ve also been experimenting with combination therapies—pairing CAR-T with chemo, cancer vaccines, and immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors—to improve its success rate. But CAR-T cells are still ineffective for at least 60 percent of blood cancer patients. And they remain in the experimental stage for solid tumors (including pancreatic cancer, mesothelioma, and glioblastoma), whose greater complexity make them harder to attack.

The new Nature study offers clues that could fuel further advances. The Penn team “profiled these cells at a level where we can almost say, ‘These are the characteristics that a T cell would need to survive 10 years,’” says Rouce, the physician at Texas Children’s Cancer Center.

One surprising finding involves how CAR-T cells change in the body over time. At first, those that Olson and Ludwig received showed the hallmarks of “killer” T-cells (also known as CD8 cells)—highly active lymphocytes bent on exterminating every tumor cell in sight. After several months, however, the population shifted toward “helper” T-cells (or CD4s), which aid in forming long-term immune memory but are normally incapable of direct aggression. Over the years, the numbers swung back and forth, until only helper cells remained. Those cells showed markers suggesting they were too exhausted to function—but in the lab, they were able not only to recognize but to destroy cancer cells.

June and his team suspect that those tired-looking helper cells had enough oomph to kill off any B cells Olson and Ludwig made, keeping the pair’s cancers permanently at bay. If so, that could prompt new approaches to selecting cells for CAR-T therapy. Maybe starting with a mix of cell types—not only CD8s, but CD4s and other varieties—would work better than using CD8s alone. Or perhaps inducing changes in cell populations at different times would help.

Another potential avenue for improvement is starting with healthier cells. Evidence from this and other trials hints that patients whose T cells are more robust to begin with respond better when their cells are used in CAR-T therapy. The Penn team recently completed a clinical trial in which CLL patients were treated with ibrutinib—a drug that enhances T-cell function—before their CAR-T cells were manufactured. The response rate, says David Porter, was “very high,” with most patients remaining cancer-free a year after being infused with the souped-up cells.

Such approaches, he adds, are essential to achieving the next phase in CAR-T therapy: “Getting it to work not just in more people, but in everybody.”

Doug Olson enjoys nature - and having a future.

Penn Medicine

To grasp what that could mean, it helps to talk with Doug Olson, who’s now 75. In the years since his infusion, he has watched his four children forge careers, and his grandkids reach their teens. He has built a business and enjoyed the rewards of semi-retirement. He’s done volunteer and advocacy work for cancer patients, run half-marathons, sailed the Caribbean, and ridden his bike along the sun-dappled roads of Silicon Valley, his current home.

And in his spare moments, he has just sat there feeling grateful. “You don’t really appreciate the effect of having a lethal disease until it’s not there anymore,” he says. “The world looks different when you have a future.”

This article was first published on Leaps.org on March 24, 2022.

Paralyzed By Polio, This British Tea Broker Changed the Course Of Medical History Forever

Robin Cavendish in his special wheelchair with his son Jonathan in the 1960s.

In December 1958, on a vacation with his wife in Kenya, a 28-year-old British tea broker named Robin Cavendish became suddenly ill. Neither he nor his wife Diana knew it at the time, but Robin's illness would change the course of medical history forever.

Robin was rushed to a nearby hospital in Kenya where the medical staff delivered the crushing news: Robin had contracted polio, and the paralysis creeping up his body was almost certainly permanent. The doctors placed Robin on a ventilator through a tracheotomy in his neck, as the paralysis from his polio infection had rendered him unable to breathe on his own – and going off the average life expectancy at the time, they gave him only three months to live. Robin and Diana (who was pregnant at the time with their first child, Jonathan) flew back to England so he could be admitted to a hospital. They mentally prepared to wait out Robin's final days.

But Robin did something unexpected when he returned to the UK – just one of many things that would astonish doctors over the next several years: He survived. Diana gave birth to Jonathan in February 1959 and continued to visit Robin regularly in the hospital with the baby. Despite doctors warning that he would soon succumb to his illness, Robin kept living.

After a year in the hospital, Diana suggested something radical: She wanted Robin to leave the hospital and live at home in South Oxfordshire for as long as he possibly could, with her as his nurse. At the time, this suggestion was unheard of. People like Robin who depended on machinery to keep them breathing had only ever lived inside hospital walls, as the prevailing belief was that the machinery needed to keep them alive was too complicated for laypeople to operate. But Diana and Robin were up for the challenges – and the risks. Because his ventilator ran on electricity, if the house were to unexpectedly lose power, Diana would either need to restore power quickly or hand-pump air into his lungs to keep him alive.

Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

In an interview as an adult, Jonathan Cavendish reflected on his parents' decision to live outside the hospital on a ventilator: "My father's mantra was quality of life," he explained. "He could have stayed in the hospital, but he didn't think that was as good of a life as he could manage. He would rather be two minutes away from death and living a full life."

After a few years of living at home, however, Robin became tired of being confined to his bed. He longed to sit outside, to visit friends, to travel – but had no way of doing so without his ventilator. So together with his friend Teddy Hall, a professor and engineer at Oxford University, the two collaborated in 1962 to create an entirely new invention: a battery-operated wheelchair prototype with a ventilator built in. With this, Robin could now venture outside the house – and soon the Cavendish family became famous for taking vacations. It was something that, by all accounts, had never been done before by someone who was ventilator-dependent. Robin and Hall also designed a van so that the wheelchair could be plugged in and powered during travel. Jonathan Cavendish later recalled a particular family vacation that nearly ended in disaster when the van broke down outside of Barcelona, Spain:

"My poor old uncle [plugged] my father's chair into the wrong socket," Cavendish later recalled, causing the electricity to short. "There was fire and smoke, and both the van and the chair ground to a halt." Johnathan, who was eight or nine at the time, his mother, and his uncle took turns hand-pumping Robin's ventilator by the roadside for the next thirty-six hours, waiting for Professor Hall to arrive in town and repair the van. Rather than being panicked, the Cavendishes managed to turn the vigil into a party. Townspeople came to greet them, bringing food and music, and a local priest even stopped by to give his blessing.

Robin had become a pioneer, showing the world that a person with severe disabilities could still have mobility, access, and a fuller quality of life than anyone had imagined. His mission, along with Hall's, then became gifting this independence to others like himself. Robin and Hall raised money – first from the Ernest Kleinwort Charitable Trust, and then from the British Department of Health – to fund more ventilator chairs, which were then manufactured by Hall's company, Littlemore Scientific Engineering, and given to fellow patients who wanted to live full lives at home. Robin and Hall used themselves as guinea pigs, testing out different models of the chairs and collaborating with scientists to create other devices for those with disabilities. One invention, called the Possum, allowed paraplegics to control things like the telephone and television set with just a nod of the head. Robin's wheelchair was not only the first of its kind; it became the model for the respiratory wheelchairs that people still use today.

Robin went on to enjoy a long and happy life with his family at their house in South Oxfordshire, surrounded by friends who would later attest to his "down-to-earth" personality, his sense of humor, and his "irresistible" charm. When he died peacefully at his home in 1994 at age 64, he was considered the world's oldest-living person who used a ventilator outside the hospital – breaking yet another barrier for what medical science thought was possible.

Kirstie Ennis, an Afghanistan veteran who survived a helicopter crash but lost a limb, pictured in May 2021 at Two Rivers Park in Colorado.

In June 2012, Kirstie Ennis was six months into her second deployment to Afghanistan and recently promoted to sergeant. The helicopter gunner and seven others were three hours into a routine mission of combat resupplies and troop transport when their CH-53D helicopter went down hard.

Miraculously, all eight people onboard survived, but Ennis' injuries were many and severe. She had a torn rotator cuff, torn labrum, crushed cervical discs, facial fractures, deep lacerations and traumatic brain injury. Despite a severely fractured ankle, doctors managed to save her foot, for a while at least.

In November 2015, after three years of constant pain and too many surgeries to count, Ennis relented. She elected to undergo a lower leg amputation but only after she completed the 1,000-mile, 72-day Walking with the Wounded journey across the UK.

On Veteran's Day of that year, on the other side of the country, orthopedic surgeon Cato Laurencin announced a moonshot challenge he was setting out to achieve on behalf of wounded warriors like Ennis: the Hartford Engineering A Limb (HEAL) Project.

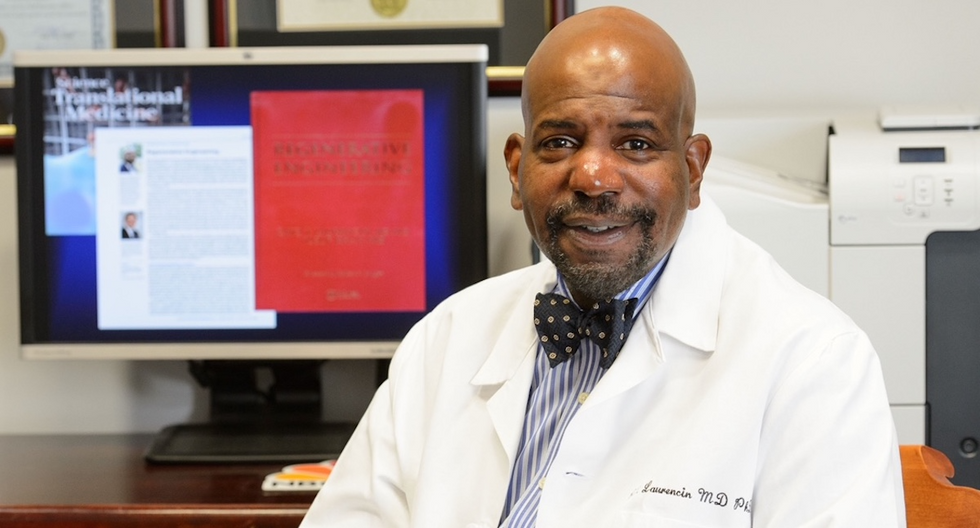

Laurencin, who is a University of Connecticut professor of chemical, materials and biomedical engineering, teamed up with experts in tissue bioengineering and regenerative medicine from Harvard, Columbia, UC Irvine and SASTRA University in India. Laurencin and his colleagues at the Connecticut Convergence Institute for Translation in Regenerative Engineering made a bold commitment to regenerate an entire limb within 15 years – by the year 2030.

Dr. Cato Laurencin pictured in his office at UConn.

Photo Credit: UConn

Regenerative Engineering -- A Whole New Field

Limb regeneration in humans has been a medical and scientific fascination for decades, with little to show for the effort. However, Laurencin believes that if we are to reach the next level of 21st century medical advances, this puzzle must be solved.

An estimated 185,000 people undergo upper or lower limb amputation every year. Despite the significant advances in electromechanical prosthetics, these individuals still lack the ability to perform complex functions such as sensation for tactile input, normal gait and movement feedback. As far as Laurencin is concerned, the only clinical answer that makes sense is to regenerate a whole functional limb.

Laurencin feels other regeneration efforts were hampered by their siloed research methods with chemists, surgeons, engineers all working separately. Success, he argues, requires a paradigm shift to a trans-disciplinary approach that brings together cutting-edge technologies from disparate fields such as biology, material sciences, physical, chemical and engineering sciences.

As the only surgeon ever inducted into the academies of Science, Medicine and Innovation, Laurencin is uniquely suited for the challenge. He is regarded as the founder of Regenerative Engineering, defined as the convergence of advanced materials sciences, stem cell sciences, physics, developmental biology and clinical translation for the regeneration of complex tissues and organ systems.

But none of this is achievable without early clinician participation across scientific fields to develop new technologies and a deeper understanding of how to harness the body's innate regenerative capabilities. "When I perform a surgical procedure or something is torn or needs to be repaired, I count on the body being involved in regenerating tissue," he says. "So, understanding how the body works to regenerate itself and harnessing that ability is an important factor for the regeneration process."

The Birth of the Vision

Laurencin's passion for regeneration began when he was a sports medicine fellow at Cornell University Medical Center in the early 1990s. There he saw a significant number of injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the major ligament that stabilizes the knee. He believed he could develop a better way to address those injuries using biomaterials to regenerate the ligament. He sketched out a preliminary drawing on a napkin one night over dinner. He has spent the next 30 years regenerating tissues, including the patented L-C ligament.

As chair of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Virginia during the peak of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Laurencin treated military personnel who survived because of improved helmets, body armor and battlefield medicine but were left with more devastating injuries, including traumatic brain injuries and limb loss.

"I was so honored to care for them and I so admired their steadfast courage that I became determined to do something big for them," says Laurencin.

When he tells people about his plans to regrow a limb, he gets a lot of eye rolls, which he finds amusing but not discouraging. Growing bone cells was relatively new when he was first focused on regenerating bone in 1987 at MIT; in 2007 he was well on his way to regenerating ligaments at UVA when many still doubted that ligaments could even be reconstructed. He and his team have already regenerated torn rotator cuff tendons and ACL ligaments using a nano-textured fabric seeded with stem cells.

Even as a finalist for the $4 million NIH Pioneer Award for high-risk/high-reward research, he faced a skeptical scientific audience in 2014. "They said, 'Well what do you plan to do?' I said 'I plan to regenerate a whole limb in people.' There was a lot of incredulousness. They stared at me and asked a lot of questions. About three days later, I received probably the best score I've ever gotten on an NIH grant."

In the Thick of the Science

Humans are born with regenerative abilities--two-year-olds have regrown fingertips--but lose that ability with age. Salamanders are the only vertebrates that can regenerate lost body parts as adults; axolotl, the rare Mexican salamander, can grow extra limbs.

The axolotl is important as a model organism because it is a four-footed vertebrate with a similar body plan to humans. Mapping the axolotl genome in 2018 enhanced scientists' genetic understanding of their evolution, development, and regeneration. Being easy to breed in captivity allowed the HEAL team to closely study these amphibians and discover a new cell type they believe may shed light on how to mimic the process in humans.

"Whenever limb regeneration takes place in the salamander, there is a huge amount of something called heparan sulfate around that area," explains Laurencin. "We thought, 'What if this heparan sulfate is the key ingredient to allowing regeneration to take place?' We found these groups of cells that were interspersed in tissues during the time of regeneration that seemed to have connections to each other that expressed this heparan sulfate."

Called GRID (Groups that are Regenerative, Interspersed and Dendritic), these cells were also recently discovered in mice. While GRID cells don't regenerate as well in mice as in salamanders, finding them in mammals was significant.

"If they're found in mice. we might be able to find these in humans in some form," Laurencin says. "We think maybe it will help us figure out regeneration or we can create cells that mimic what grid cells do and create an artificial grid cell."

What Comes Next?

Laurencin and his team have individually engineered and made every single tissue in the lower limb, including bone, cartilage, ligament, skin, nerve, blood vessels. Regenerating joints and joint tissue is the next big mile marker, which Laurencin sees as essential to regenerating a limb that functions and performs in the way he envisions.

"Using stem cells and amnion tissue, we can regenerate joints that are damaged, and have severe arthritis," he says. "We're making progress on all fronts, and making discoveries we believe are going to be helping people along the way."

That focus and advancement is vital to Ennis. After laboring over the decision to have her leg amputated below the knee, she contracted MRSA two weeks post-surgery. In less than a month, she went from a below-the-knee-amputee to a through-the-knee amputee to an above-the-knee amputee.

"A below-the-knee amputation is night-and-day from above-the-knee," she said. "You have to relearn everything. You're basically a toddler."

Kirstie Ennis pictured in July 2020.

Photo Credit: Ennis' Instagram

The clock is ticking on the timeline Laurencin set for himself. Nine years might seem like forever if you're doing time but it might appear fleeting when you're trying to create something that's never been done before. But Laurencin isn't worried. He's convinced time is on his side.

"Every week, I receive an email or a call from someone, maybe a mother whose child has lost a finger or I'm in communication with a disabled American veteran who wants to know how the progress is going. That energizes me to continue to work hard to try to create these sorts of solutions because we're talking about people and their lives."

He devotes about 60 hours a week to the project and the roughly 100 students, faculty and staff who make up the HEAL team at the Convergence Institute seem acutely aware of what's at stake and appear equally dedicated.

"We're in the thick of the science in terms of making this happen," says Laurencin. "We've moved from making the impossible possible to making the possible a reality. That's what science is all about."