Researchers Get Closer to Gene Editing Treatment for Cardiovascular Disease

Scientists are making progress to create a one-time therapy that would permanently lower LDL cholesterol to prevent heart attacks caused by high LDL.

Later this year, Verve Therapeutics of Cambridge, Ma., will initiate Phase 1 clinical trials to test VERVE-101, a new medication that, if successful, will employ gene editing to significantly reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or LDL.

LDL is sometimes referred to as the “bad” cholesterol because it collects in the walls of blood vessels, and high levels can increase chances of a heart attack, cardiovascular disease or stroke. There are approximately 600,000 heart attacks per year due to blood cholesterol damage in the United States, and heart disease is the number one cause of death in the world. According to the CDC, a 10 percent decrease in total blood cholesterol levels can reduce the incidence of heart disease by as much as 30 percent.

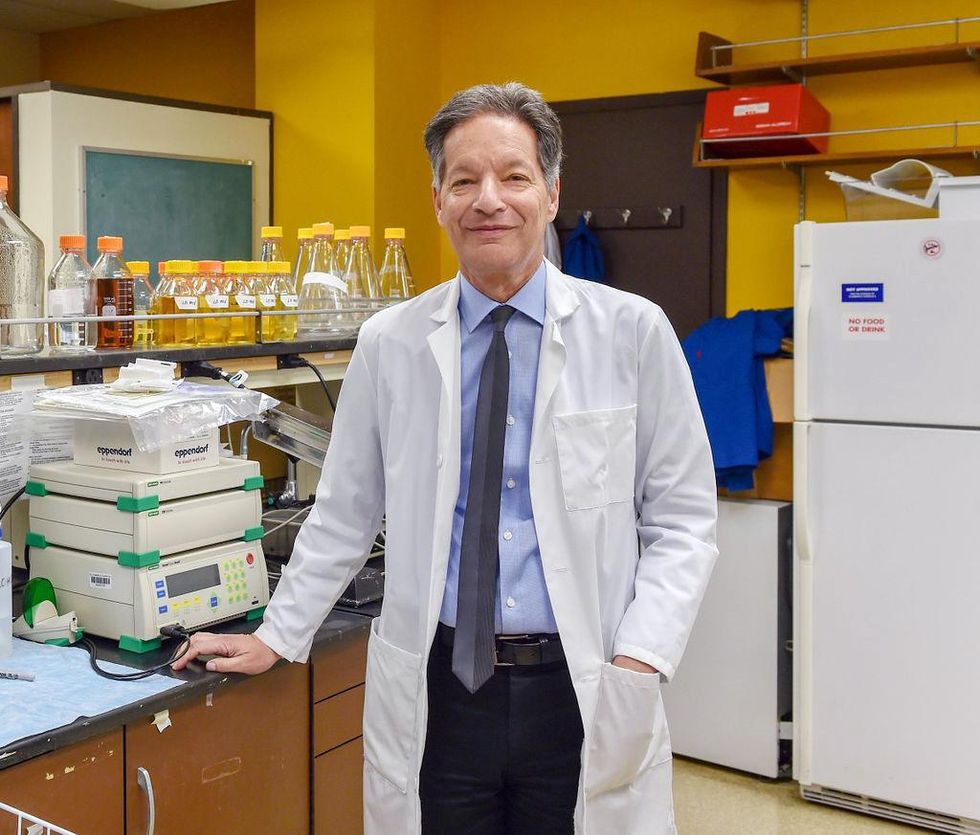

Verve’s Founder and CEO, Sekar Kathiresan, spent two decades studying the genetic basis for heart attacks while serving as a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. His research led to two critical insights.

“One is that there are some people that are naturally resistant to heart attack and have lifelong, low levels of LDL,” the cardiologist says. “Second, there are some genes that can be switched off that lead to very low LDL cholesterol, and individuals with those genes switched off are resistant to heart attacks.”

Kathiresan and his team formed a hypothesis in 2016 that if they could develop a medicine that mimics the natural protection that some people enjoy, then they might identify a powerful new way to treat and ultimately prevent heart attacks. They launched Verve in 2018 with the goal of creating a one-time therapy that would permanently lower LDL and eliminate heart attacks caused by high LDL.

"Imagine a future where somebody gets a one-time treatment at the time of their heart attack or before as a preventive measure," says Kathiresan.

The medication is targeted specifically for patients who have a genetic form of high cholesterol known as heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, or FH, caused by expression of a gene called PCSK9. Verve also plans to develop a program to silence a gene called ANGPTL3 for patients with FH and possibly those with or at risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

FH causes cholesterol to be high from birth, reaching levels of 200 to 300 milligrams per deciliter. Suggested normal levels are around 100 to 129 mg/dl, and anything above 130 mg/dl is considered high. Patients with cardiovascular disease usually are asked to aim for under 70 mg/dl, but many still have unacceptably high LDL despite taking oral medications such as statins. They are more likely to have heart attacks in their 30s, 40s and 50s, and require lifelong LDL control.

The goal for drug treatments for high LDL, Kathiresan says, is to reduce LDL as low as possible for as long as possible. Physicians and researchers also know that a sizeable portion of these patients eventually start to lose their commitment to taking their statins and other LDL-controlling medications regularly.

“If you ask 100 patients one year after their heart attack what fraction are still taking their cholesterol-lowering medications, it’s less than half,” says Kathiresan. “So imagine a future where somebody gets a one-time treatment at the time of their heart attack or before as a preventive measure. It’s right in front of us, and it’s something that Verve is looking to do.”

In late 2020, Verve completed primate testing with monkeys that had genetically high cholesterol, using a one-time intravenous injection of VERVE-101. It reduced the monkeys’ LDL by 60 percent and, 18 months later, remains at that level. Kathiresan expects the LDL to stay low for the rest of their lives.

Verve’s gene editing medication is packaged in a lipid nanoparticle to serve as the delivery mechanism into the liver when infused intravenously. The drug is absorbed and makes its way into the nucleus of the liver cells.

Verve’s program targeting PCSK9 uses precise, single base, pair base editing, Kathiresan says, meaning it doesn't cut DNA like CRISPR gene editing systems do. Instead, it changes one base, or letter, in the genome to a different one without affecting the letters around it. Comparing it to a pencil and eraser, he explains that the medication erases out a letter A and makes it a letter G in the A, C, G and T code in DNA.

“We need to continue to advance our approach and tools to make sure that we have the absolute maximum ability to detect off-target effects,” says Euan Ashley, professor of medicine and genetics at Stanford University.

By making that simple change from A to G, the medication switches off the PCSK9 gene, automatically lowering LDL cholesterol.

“Once the DNA change is made, all the cells in the liver will have that single A to G change made,” Kathiresan says. “Then the liver cells divide and give rise to future liver cells, but every time the cell divides that change, the new G is carried forward.”

Additionally, Verve is pursuing its second gene editing program to eliminate ANGPTL3, a gene that raises both LDL and blood triglycerides. In 2010, Kathiresan's research team learned that people who had that gene completely switched off had LDL and triglyceride levels of about 20 and were very healthy with no heart attacks. The goal of Verve’s medication will be to switch off that gene, too, as an option for additional LDL or triglyceride lowering.

“Success with our first drug, VERVE-101, will give us more confidence to move forward with our second drug,” Kathiresan says. “And it opens up this general idea of making [genomic] spelling changes in the liver to treat other diseases.”

The approach is less ethically concerning than other gene editing technologies because it applies somatic editing that affects only the individual patient, whereas germline editing in the patient’s sperm or egg, or in an embryo, gets passed on to children. Additionally, gene editing therapies receive the same comprehensive amount of testing for side effects as any other medicine.

“We need to continue to advance our approach and tools to make sure that we have the absolute maximum ability to detect off-target effects,” says Euan Ashley, professor of medicine and genetics at Stanford University and founding director of its Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease. Ashley and his colleagues at Stanford’s Clinical Genomics Program and beyond are increasingly excited about the promise of gene editing.

“We can offer precision diagnostics, so increasingly we’re able to define the disease at a much deeper level using molecular tools and sequencing,” he continues. “We also have this immense power of reading the genome, but we’re really on the verge of taking advantage of the power that we now have to potentially correct some of the variants that we find on a genome that contribute to disease.”

He adds that while the gene editing medicines in development to correct genomes are ahead of the delivery mechanisms needed to get them into the body, particularly the heart and brain, he’s optimistic that those aren’t too far behind.

“It will probably take a few more years before those next generation tools start to get into clinical trials,” says Ashley, whose book, The Genome Odyssey, was published last year. “The medications might be the sexier part of the research, but if you can’t get it into the right place at the right time in the right dose and not get it to the places you don’t want it to go, then that tool is not of much use.”

Medical experts consider knocking out the PCSK9 gene in patients with the fairly common genetic disorder of familial hypercholesterolemia – roughly one in 250 people – a potentially safe approach to gene editing and an effective means of significantly lowering their LDL cholesterol.

Nurse Erin McGlennon has an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator and takes medications, but she is also hopeful that a gene editing medication will be developed in the near future.

Erin McGlennon

Mary McGowan, MD, chief medical officer for The Family Heart Foundation in Pasadena, CA, sees the tremendous potential for VERVE-101 and believes patients should be encouraged by the fact that this kind of research is occurring and how much Verve has accomplished in a relatively short time. However, she offers one caveat, since even a 60 percent reduction in LDL won’t completely eliminate the need to reduce the remaining amount of LDL.

“This technology is very exciting,” she said, “but we want to stress to our patients with familial hypercholesterolemia that we know from our published research that most people require several therapies to get their LDL down., whether that be in primary prevention less than 100 mg/dl or secondary prevention less than 70 mg/dl, So Verve’s medication would be an add-on therapy for most patients.”

Dr. Kathiresan concurs: “We expect our medicine to lower LDL cholesterol by about 60 percent and that our patients will be on background oral medications, including statins that lower LDL cholesterol.”

Several leading research centers are investigating gene editing treatments for other types of cardiovascular diseases. Elizabeth McNally, Elizabeth Ward Professor and Director at the Center for Genetic Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, pursues advanced genetic correction in neuromuscular diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. A cardiologist, she and her colleagues know these diseases frequently have cardiac complications.

“Even though the field is driven by neuromuscular specialists, it’s the first therapies in patients with neuromuscular diseases that are also expected to make genetic corrections in the heart,” she says. “It’s almost like an afterthought that we’re potentially fixing the heart, too.”

Another limitation McGowan sees is that too many healthcare providers are not yet familiar with how to test patients to determine whether or not they carry genetic mutations that need to be corrected. “We need to get more genetic testing done,” she says. “For example, that’s the case with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, where a lot of the people who probably carry that diagnosis and have never been genetically identified at a time when genetic testing has never been easier.”

One patient who has been diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also happens to be a nurse working in research at Genentech Pharmaceutical, now a member of the Roche Group, in South San Francisco. To treat the disease, Erin McGlennon, RN, has an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator and takes medications, but she is also hopeful that a gene editing medication will be developed in the near future.

“With my condition, the septum muscles are just growing thicker, so I’m on medicine to keep my heart from having dangerous rhythms,” says McGlennon of the disease that carries a low risk of sudden cardiac death. “So, the possibility of having a treatment option that can significantly improve my day-to-day functioning would be a major breakthrough.”

McGlennon has some control over cardiovascular destiny through at least one currently available technology: in vitro fertilization. She’s going through it to ensure that her children won't express the gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen as soon as 18 months from now

Like all those whose kidneys have failed, Scott Burton’s life revolves around dialysis. For nearly two decades, Burton has been hooked up (or, since 2020, has hooked himself up at home) to a dialysis machine that performs the job his kidneys normally would. The process is arduous, time-consuming, and expensive. Except for a brief window before his body rejected a kidney transplant, Burton has depended on machines to take the place of his kidneys since he was 12-years-old. His whole life, the 39-year-old says, revolves around dialysis.

“Whenever I try to plan anything, I also have to plan my dialysis,” says Burton says, who works as a freelance videographer and editor. “It’s a full-time job in itself.”

Many of those on dialysis are in line for a kidney transplant that would allow them to trade thrice-weekly dialysis and strict dietary limits for a lifetime of immunosuppressants. Burton’s previous transplant means that his body will likely reject another donated kidney unless it matches perfectly—something he’s not counting on. It’s why he’s enthusiastic about the development of artificial kidneys, small wearable or implantable devices that would do the job of a healthy kidney while giving users like Burton more flexibility for traveling, working, and more.

Still, the devices aren’t ready for testing in humans—yet. But recent advancements in engineering mean that the first preclinical trials for an artificial kidney could happen as soon as 18 months from now, according to Jonathan Himmelfarb, a nephrologist at the University of Washington.

“It would liberate people with kidney failure,” Himmelfarb says.

An engineering marvel

Compared to the heart or the brain, the kidney doesn’t get as much respect from the medical profession, but its job is far more complex. “It does hundreds of different things,” says UCLA’s Ira Kurtz.

Kurtz would know. He’s worked as a nephrologist for 37 years, devoting his career to helping those with kidney disease. While his colleagues in cardiology and endocrinology have seen major advances in the development of artificial hearts and insulin pumps, little has changed for patients on hemodialysis. The machines remain bulky and require large volumes of a liquid called dialysate to remove toxins from a patient’s blood, along with gallons of purified water. A kidney transplant is the next best thing to someone’s own, functioning organ, but with over 600,000 Americans on dialysis and only about 100,000 kidney transplants each year, most of those in kidney failure are stuck on dialysis.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different.

Part of the lack of progress in artificial kidney design is the sheer complexity of the kidney’s job. To build an artificial heart, Kurtz says, you basically need to engineer a pump. An artificial pancreas needs to balance blood sugar levels with insulin secretion. While neither of these tasks is simple, they are fairly straightforward. The kidney, on the other hand, does more than get rid of waste products like urea and other toxins. Each of the 45 different cell types in the kidney do something different, helping to regulate electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and phosphorous; maintaining blood pressure and water balance; guiding the body’s hormonal and inflammatory responses; and aiding in the formation of red blood cells.

There's been little progress for patients during Ira Kurtz's 37 years as a nephrologist. Artificial kidneys would change that.

UCLA

Dialysis primarily filters waste, and does so well enough to keep someone alive, but it isn’t a true artificial kidney because it doesn’t perform the kidney’s other jobs, according to Kurtz, such as sensing levels of toxins, wastes, and electrolytes in the blood. Due to the size and water requirements of existing dialysis machines, the equipment isn’t portable. Physicians write a prescription for a certain duration of dialysis and assess how well it’s working with semi-regular blood tests. The process of dialysis itself, however, is conducted blind. Doctors can’t tell how much dialysis a patient needs based on kidney values at the time of treatment, says Meera Harhay, a nephrologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

But it’s the impact of dialysis on their day-to-day lives that creates the most problems for patients. Only one-quarter of those on dialysis are able to remain employed (compared to 85% of similar-aged adults), and many report a low quality of life. Having more flexibility in life would make a major different to her patients, Harhay says.

“Almost half their week is taken up by the burden of their treatment. It really eats away at their freedom and their ability to do things that add value to their life,” she says.

Art imitates life

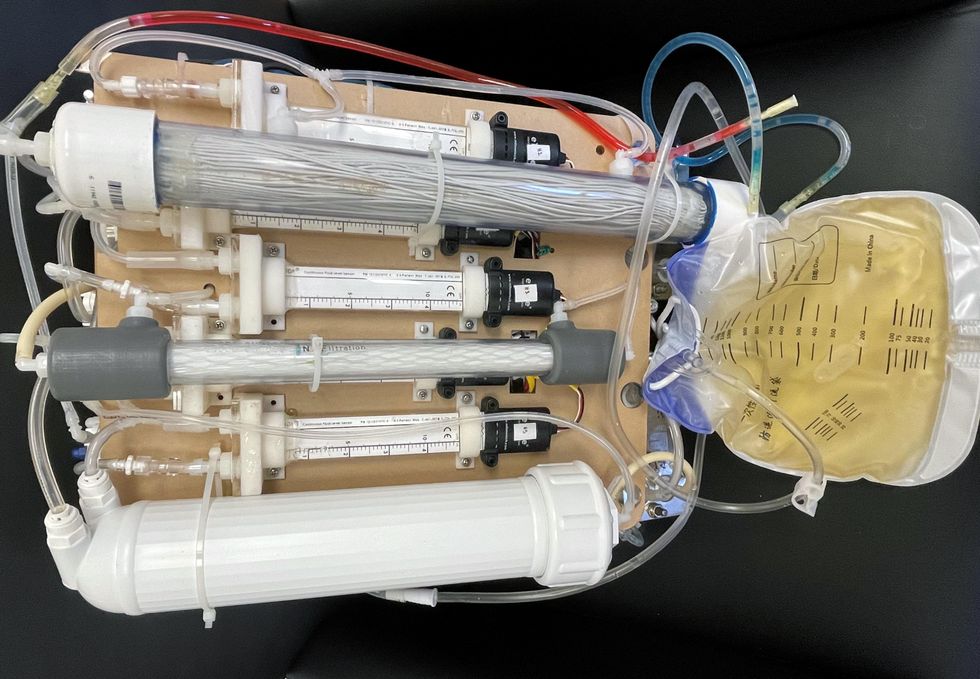

The challenge for artificial kidney designers was how to compress the kidney’s natural functions into a portable, wearable, or implantable device that wouldn’t need constant access to gallons of purified and sterilized water. The other universal challenge they faced was ensuring that any part of the artificial kidney that would come in contact with blood was kept germ-free to prevent infection.

As part of last year’s KidneyX Prize, a partnership between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the American Society of Nephrology, inventors were challenged to create prototypes for artificial kidneys. Himmelfarb’s team at the University of Washington’s Center for Dialysis Innovation won the prize by focusing on miniaturizing existing technologies to create a portable dialysis machine. The backpack sized AKTIV device (Ambulatory Kidney to Increase Vitality) will recycle dialysate in a closed loop system that removes urea from blood and uses light-based chemical reactions to convert the urea to nitrogen and carbon dioxide, which allows the dialysate to be recirculated.

Himmelfarb says that the AKTIV can be used when at home, work, or traveling, which will give users more flexibility and freedom. “If you had a 30-pound device that you could put in the overhead bins when traveling, you could go visit your grandkids,” he says.

Kurtz’s team at UCLA partnered with the U.S. Kidney Research Corporation and Arkansas University to develop a dialysate-free desktop device (about the size of a small printer) as the first phase of a progression that will he hopes will lead to something small and implantable. Part of the reason for the artificial kidney’s size, Kurtz says, is the number of functions his team are cramming into it. Not only will it filter urea from blood, but it will also use electricity to help regulate electrolyte levels in a process called electrodeionization. Kurtz emphasizes that these additional functions are what makes his design a true artificial kidney instead of just a small dialysis machine.

One version of an artificial kidney.

UCLA

“It doesn't have just a static function. It has a bank of sensors that measure chemicals in the blood and feeds that information back to the device,” Kurtz says.

Other startups are getting in on the game. Nephria Bio, a spinout from the South Korean-based EOFlow, is working to develop a wearable dialysis device, akin to an insulin pump, that uses miniature cartridges with nanomaterial filters to clean blood (Harhay is a scientific advisor to Nephria). Ian Welsford, Nephria’s co-founder and CTO, says that the device’s design means that it can also be used to treat acute kidney injuries in resource-limited settings. These potentials have garnered interest and investment in artificial kidneys from the U.S. Department of Defense.

For his part, Burton is most interested in an implantable device, as that would give him the most freedom. Even having a regular outpatient procedure to change batteries or filters would be a minor inconvenience to him.

“Being plugged into a machine, that’s not mimicking life,” he says.

Today’s more than 20,000 mental health apps have a wide range of functionalities and business models. Many of them can be useful for depression.

Even before the pandemic created a need for more telehealth options, depression was a hot area of research for app developers. Given the high prevalence of depression and its connection to suicidality — especially among today’s teenagers and young adults who grew up with mobile devices, use them often, and experience these conditions with alarming frequency — apps for depression could be not only useful but lifesaving.

“For people who are not depressed, but have been depressed in the past, the apps can be helpful for maintaining positive thinking and behaviors,” said Andrea K. Wittenborn, PhD, director of the Couple and Family Therapy Doctoral Program and a professor in human development and family studies at Michigan State University. “For people who are mildly to severely depressed, apps can be a useful complement to working with a mental health professional.”

Health and fitness apps, in general, number in the hundreds of thousands. These are driving a market expected to reach $102.45 billion by next year. The mobile mental health app market is a small part of this but still sizable at $500 million, with revenues generated through user health insurance, employers, and direct payments from individuals.

Apps can provide data that health professionals cannot gather on their own. People’s constant interaction with smartphones and wearable devices yields data on many health conditions for millions of patients in their natural environments and while they go about their usual activities. Compared with the in-office measurements of weight and blood pressure and the brevity of doctor-patient interactions, the thousands of data points gathered unobtrusively over an extended time period provide a far better and more detailed picture of the person and their health.

At their most advanced level, apps for mental health, including depression, passively gather data on how the user touches and interacts with the mobile device through changes in digital biomarkers that relate to depressive symptoms and other conditions.

Building on three decades of research since early “apps” were used for delivering treatment manuals to health professionals, today’s more than 20,000 mental health apps have a wide range of functionalities and business models. Many of these apps can be useful for depression.

Some apps primarily provide a virtual connection to a group of mental health professionals employed or contracted by the app. Others have options for meditation, sleeping or, in the case of industry leaders Calm and Headspace, overall well-being. On the cutting edge are apps that detect changes in a person’s use of mobile devices and their interactions with them.

Apps such as AbleTo, Happify Health, and Woebot Health focus on cognitive behavioral therapy, a type of counseling with proven potential to change a person’s behaviors and feelings. “CBT has been demonstrated in innumerable studies over the last several decades to be effective in the treatment of behavioral health conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders,” said Dr. Reena Pande, chief medical officer at AbleTo. “CBT is intended to be delivered as a structured intervention incorporating key elements, including behavioral activation and adaptive thinking strategies.”

These CBT skills help break the negative self-talk (rumination) common in patients with depression. They are taught and reinforced by some self-guided apps, using either artificial intelligence or programmed interactions with users. Apps can address loneliness and isolation through connections with others, even when a symptomatic person doesn’t feel like leaving the house.

At their most advanced level, apps for mental health, including depression, passively gather data on how the user touches and interacts with the mobile device through changes in “digital biomarkers” that can be associated with onset or worsening of depressive symptoms and other cognitive conditions. In one study, Mindstrong Health gathered a year’s worth of data on how people use their smartphones, such as scrolling through articles, typing and clicking. Mindstrong, whose founders include former leaders of the National Institutes of Health, modeled the timing and order of these actions to make assessments that correlated closely with gold-standard tests of cognitive function.

National organizations of mental health professionals have been following the expanding number of available apps over the years with keen interest. App Advisor is an initiative of the American Psychiatric Association that helps psychiatrists and other mental health professionals navigate the issues raised by mobile health technology. App Advisor does not rate or recommend particular apps but rather provides guidance about why apps should be assessed and how health professionals can do this.

A website that does review mental health apps is One Mind Psyber Guide, an independent nonprofit that partners with several national organizations. One Mind users can select among numerous search terms for the condition and therapeutic approach of interest. Apps are rated on a five-point scale, with reviews written by professionals in the field.

Do mental health apps related to depression have the kind of safety and effectiveness data required for medications and other medical interventions? Not always — and not often. Yet the overall results have shown early promise, Wittenborn noted.

“Studies that have attempted to detect depression from smartphone and wearable sensors [during a single session] have ranged in accuracy from about 86 to 89 percent,” Wittenborn said. “Studies that tried to predict changes in depression over time have been less accurate, with accuracy ranging from 59 to 85 percent.”

The Food and Drug Administration encourages the development of apps and has approved a few of them—mostly ones used by health professionals—but it is generally “hands off,” according to the American Psychiatric Association. The FDA has published a list of examples of software (including programming of apps) that it does not plan to regulate because they pose low risk to the public. First on the list is software that helps patients with diagnosed psychiatric conditions, including depression, maintain their behavioral coping skills by providing a “Skill of the Day” technique or message.

On its App Advisor site, the American Psychiatric Association says mental health apps can be dangerous or cause harm in multiple ways, such as by providing false information, overstating the app’s therapeutic value, selling personal data without clearly notifying users, and collecting data that isn’t relevant to mental health.

Although there is currently reason for caution, patients may eventually come to expect mental health professionals to recommend apps, especially as their rating systems, features and capabilities expand. Through such apps, patients might experience more and higher quality interactions with their mental health professionals. “Apps will continue to be refined and become more effective through future research,” said Wittenborn. “They will become more integrated into practice over time.”