Researchers Get Closer to Gene Editing Treatment for Cardiovascular Disease

Scientists are making progress to create a one-time therapy that would permanently lower LDL cholesterol to prevent heart attacks caused by high LDL.

Later this year, Verve Therapeutics of Cambridge, Ma., will initiate Phase 1 clinical trials to test VERVE-101, a new medication that, if successful, will employ gene editing to significantly reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, or LDL.

LDL is sometimes referred to as the “bad” cholesterol because it collects in the walls of blood vessels, and high levels can increase chances of a heart attack, cardiovascular disease or stroke. There are approximately 600,000 heart attacks per year due to blood cholesterol damage in the United States, and heart disease is the number one cause of death in the world. According to the CDC, a 10 percent decrease in total blood cholesterol levels can reduce the incidence of heart disease by as much as 30 percent.

Verve’s Founder and CEO, Sekar Kathiresan, spent two decades studying the genetic basis for heart attacks while serving as a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. His research led to two critical insights.

“One is that there are some people that are naturally resistant to heart attack and have lifelong, low levels of LDL,” the cardiologist says. “Second, there are some genes that can be switched off that lead to very low LDL cholesterol, and individuals with those genes switched off are resistant to heart attacks.”

Kathiresan and his team formed a hypothesis in 2016 that if they could develop a medicine that mimics the natural protection that some people enjoy, then they might identify a powerful new way to treat and ultimately prevent heart attacks. They launched Verve in 2018 with the goal of creating a one-time therapy that would permanently lower LDL and eliminate heart attacks caused by high LDL.

"Imagine a future where somebody gets a one-time treatment at the time of their heart attack or before as a preventive measure," says Kathiresan.

The medication is targeted specifically for patients who have a genetic form of high cholesterol known as heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, or FH, caused by expression of a gene called PCSK9. Verve also plans to develop a program to silence a gene called ANGPTL3 for patients with FH and possibly those with or at risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

FH causes cholesterol to be high from birth, reaching levels of 200 to 300 milligrams per deciliter. Suggested normal levels are around 100 to 129 mg/dl, and anything above 130 mg/dl is considered high. Patients with cardiovascular disease usually are asked to aim for under 70 mg/dl, but many still have unacceptably high LDL despite taking oral medications such as statins. They are more likely to have heart attacks in their 30s, 40s and 50s, and require lifelong LDL control.

The goal for drug treatments for high LDL, Kathiresan says, is to reduce LDL as low as possible for as long as possible. Physicians and researchers also know that a sizeable portion of these patients eventually start to lose their commitment to taking their statins and other LDL-controlling medications regularly.

“If you ask 100 patients one year after their heart attack what fraction are still taking their cholesterol-lowering medications, it’s less than half,” says Kathiresan. “So imagine a future where somebody gets a one-time treatment at the time of their heart attack or before as a preventive measure. It’s right in front of us, and it’s something that Verve is looking to do.”

In late 2020, Verve completed primate testing with monkeys that had genetically high cholesterol, using a one-time intravenous injection of VERVE-101. It reduced the monkeys’ LDL by 60 percent and, 18 months later, remains at that level. Kathiresan expects the LDL to stay low for the rest of their lives.

Verve’s gene editing medication is packaged in a lipid nanoparticle to serve as the delivery mechanism into the liver when infused intravenously. The drug is absorbed and makes its way into the nucleus of the liver cells.

Verve’s program targeting PCSK9 uses precise, single base, pair base editing, Kathiresan says, meaning it doesn't cut DNA like CRISPR gene editing systems do. Instead, it changes one base, or letter, in the genome to a different one without affecting the letters around it. Comparing it to a pencil and eraser, he explains that the medication erases out a letter A and makes it a letter G in the A, C, G and T code in DNA.

“We need to continue to advance our approach and tools to make sure that we have the absolute maximum ability to detect off-target effects,” says Euan Ashley, professor of medicine and genetics at Stanford University.

By making that simple change from A to G, the medication switches off the PCSK9 gene, automatically lowering LDL cholesterol.

“Once the DNA change is made, all the cells in the liver will have that single A to G change made,” Kathiresan says. “Then the liver cells divide and give rise to future liver cells, but every time the cell divides that change, the new G is carried forward.”

Additionally, Verve is pursuing its second gene editing program to eliminate ANGPTL3, a gene that raises both LDL and blood triglycerides. In 2010, Kathiresan's research team learned that people who had that gene completely switched off had LDL and triglyceride levels of about 20 and were very healthy with no heart attacks. The goal of Verve’s medication will be to switch off that gene, too, as an option for additional LDL or triglyceride lowering.

“Success with our first drug, VERVE-101, will give us more confidence to move forward with our second drug,” Kathiresan says. “And it opens up this general idea of making [genomic] spelling changes in the liver to treat other diseases.”

The approach is less ethically concerning than other gene editing technologies because it applies somatic editing that affects only the individual patient, whereas germline editing in the patient’s sperm or egg, or in an embryo, gets passed on to children. Additionally, gene editing therapies receive the same comprehensive amount of testing for side effects as any other medicine.

“We need to continue to advance our approach and tools to make sure that we have the absolute maximum ability to detect off-target effects,” says Euan Ashley, professor of medicine and genetics at Stanford University and founding director of its Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Disease. Ashley and his colleagues at Stanford’s Clinical Genomics Program and beyond are increasingly excited about the promise of gene editing.

“We can offer precision diagnostics, so increasingly we’re able to define the disease at a much deeper level using molecular tools and sequencing,” he continues. “We also have this immense power of reading the genome, but we’re really on the verge of taking advantage of the power that we now have to potentially correct some of the variants that we find on a genome that contribute to disease.”

He adds that while the gene editing medicines in development to correct genomes are ahead of the delivery mechanisms needed to get them into the body, particularly the heart and brain, he’s optimistic that those aren’t too far behind.

“It will probably take a few more years before those next generation tools start to get into clinical trials,” says Ashley, whose book, The Genome Odyssey, was published last year. “The medications might be the sexier part of the research, but if you can’t get it into the right place at the right time in the right dose and not get it to the places you don’t want it to go, then that tool is not of much use.”

Medical experts consider knocking out the PCSK9 gene in patients with the fairly common genetic disorder of familial hypercholesterolemia – roughly one in 250 people – a potentially safe approach to gene editing and an effective means of significantly lowering their LDL cholesterol.

Nurse Erin McGlennon has an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator and takes medications, but she is also hopeful that a gene editing medication will be developed in the near future.

Erin McGlennon

Mary McGowan, MD, chief medical officer for The Family Heart Foundation in Pasadena, CA, sees the tremendous potential for VERVE-101 and believes patients should be encouraged by the fact that this kind of research is occurring and how much Verve has accomplished in a relatively short time. However, she offers one caveat, since even a 60 percent reduction in LDL won’t completely eliminate the need to reduce the remaining amount of LDL.

“This technology is very exciting,” she said, “but we want to stress to our patients with familial hypercholesterolemia that we know from our published research that most people require several therapies to get their LDL down., whether that be in primary prevention less than 100 mg/dl or secondary prevention less than 70 mg/dl, So Verve’s medication would be an add-on therapy for most patients.”

Dr. Kathiresan concurs: “We expect our medicine to lower LDL cholesterol by about 60 percent and that our patients will be on background oral medications, including statins that lower LDL cholesterol.”

Several leading research centers are investigating gene editing treatments for other types of cardiovascular diseases. Elizabeth McNally, Elizabeth Ward Professor and Director at the Center for Genetic Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, pursues advanced genetic correction in neuromuscular diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. A cardiologist, she and her colleagues know these diseases frequently have cardiac complications.

“Even though the field is driven by neuromuscular specialists, it’s the first therapies in patients with neuromuscular diseases that are also expected to make genetic corrections in the heart,” she says. “It’s almost like an afterthought that we’re potentially fixing the heart, too.”

Another limitation McGowan sees is that too many healthcare providers are not yet familiar with how to test patients to determine whether or not they carry genetic mutations that need to be corrected. “We need to get more genetic testing done,” she says. “For example, that’s the case with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, where a lot of the people who probably carry that diagnosis and have never been genetically identified at a time when genetic testing has never been easier.”

One patient who has been diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy also happens to be a nurse working in research at Genentech Pharmaceutical, now a member of the Roche Group, in South San Francisco. To treat the disease, Erin McGlennon, RN, has an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator and takes medications, but she is also hopeful that a gene editing medication will be developed in the near future.

“With my condition, the septum muscles are just growing thicker, so I’m on medicine to keep my heart from having dangerous rhythms,” says McGlennon of the disease that carries a low risk of sudden cardiac death. “So, the possibility of having a treatment option that can significantly improve my day-to-day functioning would be a major breakthrough.”

McGlennon has some control over cardiovascular destiny through at least one currently available technology: in vitro fertilization. She’s going through it to ensure that her children won't express the gene for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

In this week's Friday Five, an old diabetes drug finds an exciting new purpose. Plus, how to make the cities of the future less toxic, making old mice younger with EVs, a new reason for mysterious stillbirths - and much more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Here is the promising research covered in this week's Friday Five:

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

- How to make cities of the future less noisy

- An old diabetes drug could have a new purpose: treating an irregular heartbeat

- A new reason for mysterious stillbirths

- Making old mice younger with EVs

- No pain - or mucus - no gain

And an honorable mention this week: How treatments for depression can change the structure of the brain

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

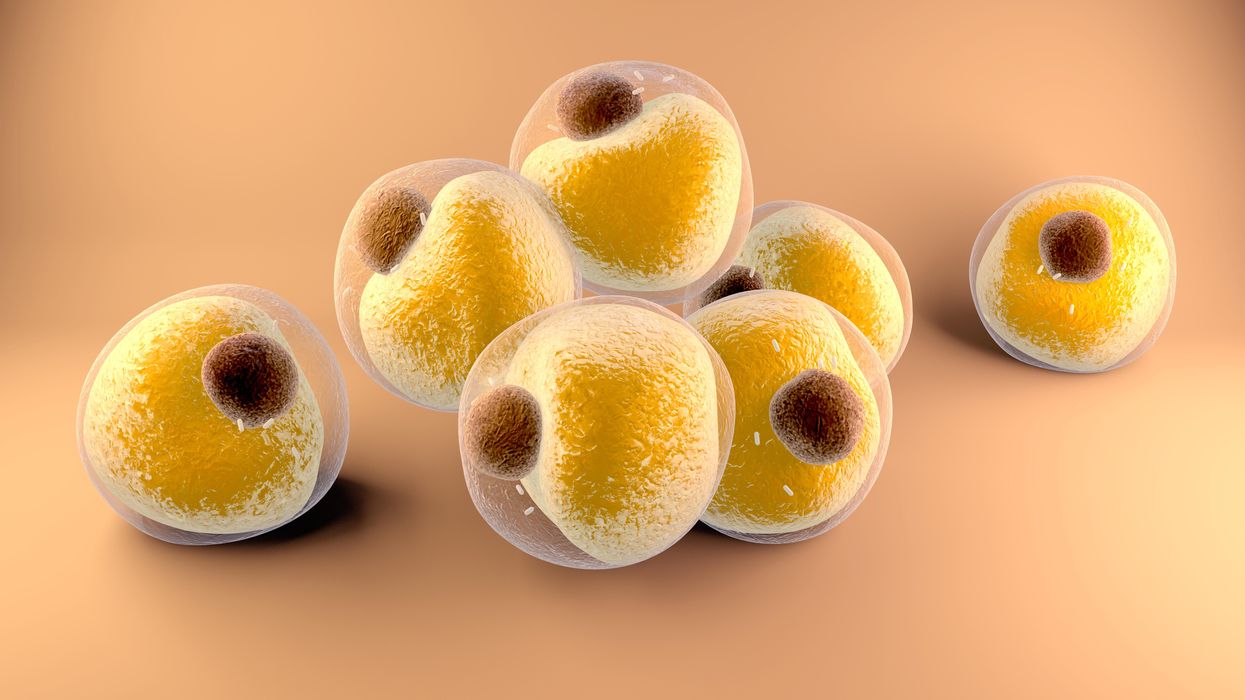

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.