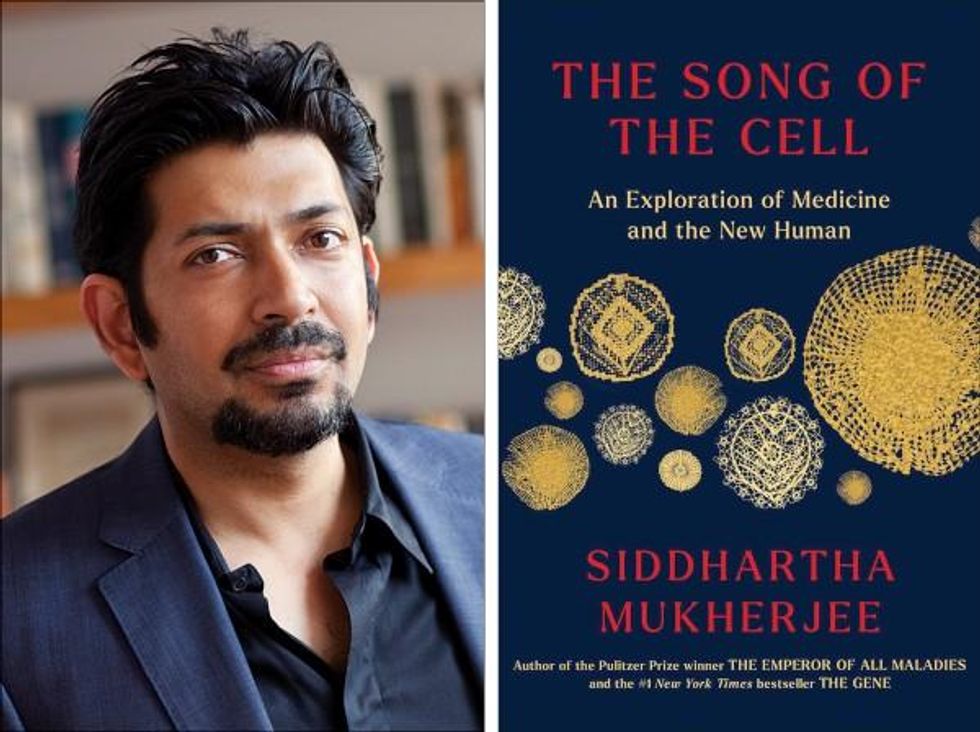

Life is Emerging: Review of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s Song of the Cell

A new book by Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee will be released from Simon & Schuster on October 25, 2022.

The DNA double helix is often the image spiraling at the center of 21st century advances in biomedicine and the growing bioeconomy. And yet, DNA is molecularly inert. DNA, the code for genes, is not alive and is not strictly necessary for life. Ought life be at the center of our communication of living systems? Is not the Cell a superior symbol of life and our manipulation of living systems?

A code for life isn’t a code without the life that instantiates it. A code for life must be translated. The cell is the basic unit of that translation. The cell is the minimal viable package of life as we know it. Therefore, cell biology is at the center of biomedicine’s greatest transformations, suggests Pulitzer-winning physician-scientist Siddhartha Mukherjee in his latest book, The Song of the Cell: The Exploration of Medicine and the New Human.

The Song of the Cell begins with the discovery of cells and of germ theory, featuring characters such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, who brought the cell “into intimate contact with pathology and medicine.” This intercourse would transform biomedicine, leading to the insight that we can treat disease by thinking at the cellular level. The slightest rearrangement of sick cells might be the path toward alleviating suffering for the organism: eroding the cell walls of a bacterium while sparing our human cells; inventing a medium that coaxes sperm and egg to dance into cellular union for in vitro fertilization (IVF); designing molecular missiles that home to the receptors decorating the exterior of cancer cells; teaching adult skin cells to remember their embryonic state for regenerative medicines.

Mukherjee uses the bulk of the book to elucidate key cell types in the human body, along with their “connective relationships” that enable key organs and organ systems to function. This includes the immune system, the heart, the brain, and so on. Mukherjee’s distinctive style features compelling anecdotes and human stories that animate the scientific (and unscientific) processes that have led to our current state of understanding. In his chapter on neurons and the brain, for example, he integrates Santiago Ramon y Cajal’s meticulous black ink sketches of neurons into Mukherjee’s own personal encounter with clinical depression. In one lucid section, he interviews Dr. Helen Mayberg, a pioneering neurologist who takes seriously the descriptive power of her patients’ metaphors, as they suffer from “caves,” “holes,” “voids,” and “force fields” that render their lives gray. Dr. Mayberg aims to stimulate patients’ neuronal cells in a manner that brings back the color.

Beyond exposing the insight and inventiveness that has arisen out of cell-based thinking, it seems that Mukherjee’s bigger project is an epistemological one. The early chapters of The Song of the Cell continually hint at the potential for redefining the basic unit of biology as the cell rather than the gene. The choice to center biomedicine around cells is, above all, a conspicuous choice not to center it around genes (the subject of Mukherjee’s previous book, The Gene), because genes dominate popular science communication.

This choice of cells over genes is most welcome. Cells are alive. Genes are not. Letters—such as the As, Cs, Gs, and Ts that represent the nucleotides of DNA, which make up our genes—must be synthesized into a word or poem or song that offers a glimpse into deeper truths. A key idea embedded in this thinking is that of emergence. Whether in ancient myth or modern art, creation tends to be an emergent process, not a linearly coded script. The cell is our current best guess for the basic unit of life’s emergence, turning a finite set of chemical building blocks—nucleic acids, proteins, sugars, fats—into a replicative, evolving system for fighting stasis and entropy. The cell’s song is one for our times, for it is the song of biology’s emergence out of chemistry and physics, into the “frenetically active process” of homeostasis.

Re-centering our view of biology has practical consequences, too, for how we think about diagnosing and treating disease, and for inventing new medicines. Centering cells presents a challenge: which type of cell to place at the center? Rather than default to the apparent simplicity of DNA as a symbol because it represents the one master code for life, the tension in defining the diversity of cells—a mapping process still far from complete in cutting-edge biology laboratories—can help to create a more thoughtful library of cellular metaphors to shape both the practice and communication of biology.

Further, effective problem solving is often about operating at the right level, or the right scale. The cell feels like appropriate level at which to interrogate many of the diseases that ail us, because the senses that guide our own perceptions of sickness and health—the smoldering pain of inflammation, the tunnel vision of a migraine, the dizziness of a fluttering heart—are emergent.

This, unfortunately, is sort of where Mukherjee leaves the reader, under-exploring the consequences of a biology of emergence. Many practical and profound questions have to do with the ways that each scale of life feeds back on the others. In a tome on Cells and “the future human” I wished that Mukherjee had created more space for seeking the ways that cells will shape and be shaped by the future, of humanity and otherwise.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts.

For example, when discussing the regenerative power of pluripotent stem cells, Mukherjee raises the philosophical thought experiment of the Delphic boat, also known as the Ship of Theseus. The boat is made of many pieces of wood, each of which is replaced for repairs over the years, with the boat’s structure unchanged. Eventually none of the boat’s original wood remains: Is it the same boat?

Mukherjee raises the Delphic boat in one paragraph at the end of the chapter on stem cells, as a metaphor related to the possibility of stem cell-enabled regeneration in perpetuity. He does not follow any of the threads of potential answers. Given the current state of cellular engineering, about which Mukherjee is a world expert from his work as a physician-scientist, this book could have used an entire section dedicated to probing this question and, importantly, the ways this thought experiment falls apart.

We are entering a phase of real-world bioengineering that features the modularization of cellular parts within cells, of cells within organs, of organs within bodies, and of bodies within ecosystems. In this reality, we would be unwise to assume that any whole is the mere sum of its parts. Wholeness at any one of these scales of life—organelle, cell, organ, body, ecosystem—is what is at stake if we allow biological reductionism to assume away the relation between those scales.

In other words, Mukherjee succeeds in providing a masterful and compelling narrative of the lives of many of the cells that emerge to enliven us. Like his previous books, it is a worthwhile read for anyone curious about the role of cells in disease and in health. And yet, he fails to offer the broader context of The Song of the Cell.

As leading agronomist and essayist Wes Jackson has written, “The sequence of amino acids that is at home in the human cell, when produced inside the bacterial cell, does not fold quite right. Something about the E. coli internal environment affects the tertiary structure of the protein and makes it inactive. The whole in this case, the E. coli cell, affects the part—the newly made protein. Where is the priority of part now?” [1]

Beyond the ways that different kingdoms of life translate the same genetic code, the practical situation for humanity today relates to the ways that the different disciplines of modern life use values and culture to influence our genes, cells, bodies, and environment. It may be that humans will soon become a bit like the Delphic boat, infused with the buzz of fresh cells to repopulate different niches within our bodies, for healthier, longer lives. But in biology, as in writing, a mixed metaphor can cause something of a cacophony. For we are not boats with parts to be replaced piecemeal. And nor are whales, nor alpine forests, nor topsoil. Life isn’t a sum of parts, and neither is a song that rings true.

[1] Wes Jackson, "Visions and Assumptions," in Nature as Measure (p. 52-53).

The Voice Behind Some of Your Favorite Cartoon Characters Helped Create the Artificial Heart

This Jarvik-7 artificial heart was used in the first bridge operation in 1985 meant to replace a failing heart while the patient waited for a donor organ.

In June, a team of surgeons at Duke University Hospital implanted the latest model of an artificial heart in a 39-year-old man with severe heart failure, a condition in which the heart doesn't pump properly. The man's mechanical heart, made by French company Carmat, is a new generation artificial heart and the first of its kind to be transplanted in the United States. It connects to a portable external power supply and is designed to keep the patient alive until a replacement organ becomes available.

Many patients die while waiting for a heart transplant, but artificial hearts can bridge the gap. Though not a permanent solution for heart failure, artificial hearts have saved countless lives since their first implantation in 1982.

What might surprise you is that the origin of the artificial heart dates back decades before, when an inventive television actor teamed up with a famous doctor to design and patent the first such device.

A man of many talents

Paul Winchell was an entertainer in the 1950s and 60s, rising to fame as a ventriloquist and guest-starring as an actor on programs like "The Ed Sullivan Show" and "Perry Mason." When children's animation boomed in the 1960s, Winchell made a name for himself as a voice actor on shows like "The Smurfs," "Winnie the Pooh," and "The Jetsons." He eventually became famous for originating the voices of Tigger from "Winnie the Pooh" and Gargamel from "The Smurfs," among many others.

But Winchell wasn't just an entertainer: He also had a quiet passion for science and medicine. Between television gigs, Winchell busied himself working as a medical hypnotist and acupuncturist, treating the same Hollywood stars he performed alongside. When he wasn't doing that, Winchell threw himself into engineering and design, building not only the ventriloquism dummies he used on his television appearances but a host of products he'd dreamed up himself. Winchell spent hours tinkering with his own inventions, such as a set of battery-powered gloves and something called a "flameless lighter." Over the course of his life, Winchell designed and patented more than 30 of these products – mostly novelties, but also serious medical devices, such as a portable blood plasma defroster.

| Ventriloquist Paul Winchell with Jerry Mahoney, his dummy, in 1951 |

A meeting of the minds

In the early 1950s, Winchell appeared on a variety show called the "Arthur Murray Dance Party" and faced off in a dance competition with the legendary Ricardo Montalban (Winchell won). At a cast party for the show later that same night, Winchell met Dr. Henry Heimlich – the same doctor who would later become famous for inventing the Heimlich maneuver, who was married to Murray's daughter. The two hit it off immediately, bonding over their shared interest in medicine. Before long, Heimlich invited Winchell to come observe him in the operating room at the hospital where he worked. Winchell jumped at the opportunity, and not long after he became a frequent guest in Heimlich's surgical theatre, fascinated by the mechanics of the human body.

One day while Winchell was observing at the hospital, he witnessed a patient die on the operating table after undergoing open-heart surgery. He was suddenly struck with an idea: If there was some way doctors could keep blood pumping temporarily throughout the body during surgery, patients who underwent risky operations like open-heart surgery might have a better chance of survival. Winchell rushed to Heimlich with the idea – and Heimlich agreed to advise Winchell and look over any design drafts he came up with. So Winchell went to work.

Winchell's heart

As it turned out, building ventriloquism dummies wasn't that different from building an artificial heart, Winchell noted later in his autobiography – the shifting valves and chambers of the mechanical heart were similar to the moving eyes and opening mouths of his puppets. After each design, Winchell would go back to Heimlich and the two would confer, making adjustments along the way to.

By 1956, Winchell had perfected his design: The "heart" consisted of a bag that could be placed inside the human body, connected to a battery-powered motor outside of the body. The motor enabled the bag to pump blood throughout the body, similar to a real human heart. Winchell received a patent for the design in 1963.

At the time, Winchell never quite got the credit he deserved. Years later, researchers at the University of Utah, working on their own artificial heart, came across Winchell's patent and got in touch with Winchell to compare notes. Winchell ended up donating his patent to the team, which included Dr. Richard Jarvik. Jarvik expanded on Winchell's design and created the Jarvik-7 – the world's first artificial heart to be successfully implanted in a human being in 1982.

The Jarvik-7 has since been replaced with newer, more efficient models made up of different synthetic materials, allowing patients to live for longer stretches without the heart clogging or breaking down. With each new generation of hearts, heart failure patients have been able to live relatively normal lives for longer periods of time and with fewer complications than before – and it never would have been possible without the unsung genius of a puppeteer and his love of science.

Elaine Kamil had just returned home after a few days of business meetings in 2013 when she started having chest pains. At first Kamil, then 66, wasn't worried—she had had some chest pain before and recently went to a cardiologist to do a stress test, which was normal.

"I can't be having a heart attack because I just got checked," she thought, attributing the discomfort to stress and high demands of her job. A pediatric nephrologist at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, she takes care of critically ill children who are on dialysis or are kidney transplant patients. Supporting families through difficult times and answering calls at odd hours is part of her daily routine, and often leaves her exhausted.

She figured the pain would go away. But instead, it intensified that night. Kamil's husband drove her to the Cedars-Sinai hospital, where she was admitted to the coronary care unit. It turned out she wasn't having a heart attack after all. Instead, she was diagnosed with a much less common but nonetheless dangerous heart condition called takotsubo syndrome, or broken heart syndrome.

A heart attack happens when blood flow to the heart is obstructed—such as when an artery is blocked—causing heart muscle tissue to die. In takotsubo syndrome, the blood flow isn't blocked, but the heart doesn't pump it properly. The heart changes its shape and starts to resemble a Japanese fishing device called tako-tsubo, a clay pot with a wider body and narrower mouth, used to catch octopus.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks," explains Noel Bairey Merz, the cardiologist at Cedar Sinai who Kamil went to see after she was discharged.

"The heart muscle is stunned and doesn't function properly anywhere from three days to three weeks."

But even though the heart isn't permanently damaged, mortality rates due to takotsubo syndrome are comparable to those of a heart attack, Merz notes—about 4-5% of patients die from the attack, and 20% within the next five years. "It's as bad as a heart attack," Merz says—only it's much less known, even to doctors. The condition affects only about 1% of people, and there are around 15,000 new cases annually. It's diagnosed using a cardiac ventriculogram, an imaging test that allows doctors to see how the heart pumps blood.

Scientists don't fully understand what causes Takotsubo syndrome, but it usually occurs after extreme emotional or physical stress. Doctors think it's triggered by a so-called catecholamine storm, a phenomenon in which the body releases too much catecholamines—hormones involved in the fight-or-flight response. Evolutionarily, when early humans lived in savannas or forests and had to either fight off predators or flee from them, these hormones gave our ancestors the needed strength and stamina to take either action. Released by nerve endings and by the adrenal glands that sit on top of the kidneys, these hormones still flood our bodies in moments of stress, but an overabundance of them could sometimes be damaging.

Elaine Kamil

A recent study by scientists at Harvard Medical School linked increased risk of takotsubo to higher activity in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for emotions that's involved in responses to stress. The scientists believe that chronic stress makes people more susceptible to the syndrome. Notably, one small study suggested that the number of Takotsubo cases increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are no specific drugs to treat takotsubo, so doctors rely on supportive therapies, which include medications typically used for high blood pressure and heart failure. In most cases, the heart returns to its normal shape within a few weeks. "It's a spontaneous recovery—the catecholamine storm is resolved, the injury trigger is removed and the heart heals itself because our bodies have an amazing healing capacity," Merz says. It also helps that tissues remain intact. 'The heart cells don't die, they just aren't functioning properly for some time."

That's the good news. The bad news is that takotsubo is likely to strike again—in 5-20% of patients the condition comes back, sometimes more severe than before.

That's exactly what happened to Kamil. After getting her diagnosis in 2013, she realized that she actually had a previous takotsubo episode. In 2010, she experienced similar symptoms after her son died. "The night after he died, I was having severe chest pain at night, but I was too overwhelmed with grief to do anything about it," she recalls. After a while, the pain subsided and didn't return until three years later.

For weeks after her second attack, she felt exhausted, listless and anxious. "You lose confidence in your body," she says. "You have these little twinges on your chest, or if you start having arrhythmia, and you wonder if this is another episode coming up. It's really unnerving because you don't know how to read these cues." And that's very typical, Merz says. Even when the heart muscle appears to recover, patients don't return to normal right away. They have shortens of breath, they can't exercise, and they stay anxious and worried for a while.

Women over the age of 50 are diagnosed with takotsubo more often than other demographics. However, it happens in men too, although it typically strikes after physical stress, such as a triathlon or an exhausting day of cycling. Young people can also get takotsubo. Older patients are hospitalized more often, but younger people tend to have more severe complications. It could be because an older person may go for a jog while younger one may run a marathon, which would take a stronger toll on the body of a person who's predisposed to the condition.

Notably, the emotional stressors don't always have to be negative—the heart muscle can get out of shape from good emotions, too. "There have been case reports of takotsubo at weddings," Merz says. Moreover, one out of three or four takotsubo patients experience no apparent stress, she adds. "So it could be that it's not so much the catecholamine storm itself, but the body's reaction to it—the physiological reaction deeply embedded into out physiology," she explains.

Merz and her team are working to understand what makes people predisposed to takotsubo. They think a person's genetics play a role, but they haven't yet pinpointed genes that seem to be responsible. Genes code for proteins, which affect how the body metabolizes various compounds, which, in turn, affect the body's response to stress. Pinning down the protein involved in takotsubo susceptibility would allow doctors to develop screening tests and identify those prone to severe repeating attacks. It will also help develop medications that can either prevent it or treat it better than just waiting for the body to heal itself.

Researchers at the Imperial College London recently found that elevated levels of certain types of microRNAs—molecules involved in protein production—increase the chances of developing takotsubo.

In one study, researchers tried treating takotsubo in mice with a drug called suberanilohydroxamic acid, or SAHA, typically used for cancer treatment. The drug improved cardiac health and reversed the broken heart in rodents. It remains to be seen if the drug would have a similar effect on humans. But identifying a drug that shows promise is progress, Merz says. "I'm glad that there's research in this area."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.