Staying well in the 21st century is like playing a game of chess

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

The control of infectious diseases was considered to be one of the “10 Great Public Health Achievements.” What we didn’t take into account was the very concept of evolution: as we built better protections, our enemies eventually boosted their attacking prowess, so soon enough we found ourselves on the defensive once again.

This article originally appeared in One Health/One Planet, a single-issue magazine that explores how climate change and other environmental shifts are increasing vulnerabilities to infectious diseases by land and by sea. The magazine probes how scientists are making progress with leaders in other fields toward solutions that embrace diverse perspectives and the interconnectedness of all lifeforms and the planet.

On July 30, 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report comparing data on the control of infectious disease from the beginning of the 20th century to the end. The data showed that deaths from infectious diseases declined markedly. In the early 1900s, pneumonia, tuberculosis and diarrheal diseases were the three leading killers, accounting for one-third of total deaths in the U.S.—with 40 percent being children under five.

Mass vaccinations, the discovery of antibiotics and overall sanitation and hygiene measures eventually eradicated smallpox, beat down polio, cured cholera, nearly rid the world of tuberculosis and extended the U.S. life expectancy by 25 years. By 1997, there was a shift in population health in the U.S. such that cancer, diabetes and heart disease were now the leading causes of death.

The control of infectious diseases is considered to be one of the “10 Great Public Health Achievements.” Yet on the brink of the 21st century, new trouble was already brewing. Hospitals were seeing periodic cases of antibiotic-resistant infections. Novel viruses, or those that previously didn’t afflict humans, began to emerge, causing outbreaks of West Nile, SARS, MERS or swine flu.In the years that followed, tuberculosis made a comeback, at least in certain parts of the world. What we didn’t take into account was the very concept of evolution: as we built better protections, our enemies eventually boosted their attacking prowess, so soon enough we found ourselves on the defensive once again.

At the same time, new, previously unknown or extremely rare disorders began to rise, such as autoimmune or genetic conditions. Two decades later, scientists began thinking about health differently—not as a static achievement guaranteed to last, but as something dynamic and constantly changing—and sometimes, for the worse.

What emerged since then is a different paradigm that makes our interactions with the microbial world more like a biological chess match, says Victoria McGovern, a biochemist and program officer for the Burroughs Wellcome Fund’s Infectious Disease and Population Sciences Program. In this chess game, humans may make a clever strategic move, which could involve creating a new vaccine or a potent antibiotic, but that advantage is fleeting. At some point, the organisms we are up against could respond with a move of their own—such as developing resistance to medication or genetic mutations that attack our bodies. Simply eradicating the “opponent,” or the pathogenic microbes, as efficiently as possible isn’t enough to keep humans healthy long-term.

Instead, scientists should focus on studying the complexity of interactions between humans and their pathogens. “We need to better understand the lifestyles of things that afflict us,” McGovern says. “The solutions are going to be in understanding various parts of their biology so we can influence how they behave around our systems.”

Genetics and cell biology, combined with imaging techniques that allow one to see tissues and individual cells in actions, will enable scientists to define and quantify what it means to be healthy at the molecular level.

What is being proposed will require a pivot to basic biology and other disciplines that have suffered from lack of research funding in recent years. Yet, according to McGovern, the research teams of funded proposals are answering bigger questions. “We look for people exploring questions about hosts and pathogens, and what happens when they touch, but we’re also looking for people with big ideas,” she says. For example, if one specific infection causes a chain of pathological events in the body, can other infections cause them too? And if we find a way to break that chain for one pathogen, can we play the same trick on another? “We really want to see people thinking of not just one experiment but about big implications of their work,” McGovern says.

Jonah Cool, a cell biologist, geneticist and science officer at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, says that it’s necessary to define what constitutes a healthy organism and how it overcomes infections or environmental assaults, such as pollution from forest fires or toxins from industrial smokestacks. An organism that catches a disease isn’t necessarily an unhealthy one, as long as it fights it off successfully—an ability that arises from the complex interplay of its genes, the immune system, age, stress levels and other factors. Modern science allows many of these factors to be measured, recorded and compared. “We need a data-driven, deep-phenotyping approach to defining healthy biological systems and their responses to insults—which can be infectious disease or environmental exposures—and their ability to navigate their way through that space,” Cool says.

Genetics and cell biology, combined with imaging techniques that allow one to see tissues and individual cells in actions, will enable scientists to define and quantify what it means to be healthy at the molecular level. “As a geneticist and cell biologist, I believe in all these molecular underpinnings and how they arise in phenotypic differences in cells, genes, proteins—and how their combinations form complex cellular states,” Cool says.

Julie Graves, a physician, public health consultant, former adjunct professor of management, policy and community health at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston, stresses the necessity of nutritious diets. According to the Rockefeller Food Initiative, “poor diet is the leading risk factor for disease, disability and premature death in the majority of countries around the world.” Adequate nutrition is critical for maintaining human health and life. Yet, Western diets are often low in essential nutrients, high in calories and heavy on processed foods. Overconsumption of these foods has contributed to high rates of obesity and chronic disease in the U.S. In fact, more than half of American adults have at least one chronic disease, and 27 percent have more than one—which increases vulnerability to COVID-19 infections, according to the 2018 National Health Interview Survey.

Further, the contamination of our food supply with various agricultural and industrial toxins—petrochemicals, pesticides, PFAS and others—has implications for morbidity, mortality, and overall quality of life. “These chemicals are insidiously in everything, including our bodies,” Graves says—and they are interfering with our normal biological functions. “We need to stop how we manufacture food,” she adds, and rid our sustenance of these contaminants.

According to the Humane Society of the United States, factory farms result in nearly 40 percent of emissions of methane. Concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs may serve as breeding grounds for pandemics, scientists warn, so humans should research better ways to raise and treat livestock. Diego Rose, a professor of food and nutrition policy at Tulane University School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine, and his colleagues found that “20 percent of Americans’ diets account for about 45 percent of the environmental impacts [that come from food].” A subsequent study explored the impacts of specific foods and found that substituting beef for chicken lowers an individual’s carbon footprint by nearly 50 percent, with water usage decreased by 30 percent. Notably, however, eating too much red meat has been associated with a variety of illnesses.

In some communities, the option to swap food types is limited or impossible. For example, “many populations live in relative food deserts where there’s not a local grocery store that has any fresh produce,” says Louis Muglia, the president and CEO of Burroughs Wellcome. Individuals in these communities suffer from an insufficient intake of beneficial macronutrients, and they’re “probably being exposed to phenols and other toxins that are in the packaging.” An equitable, sustainable and nutritious food supply will be vital to humanity’s wellbeing in the era of climate change, unpredictable weather and spillover events.

A recent report by See Change Institute and the Climate Mental Health Network showed that people who are experiencing socioeconomic inequalities, including many people of color, contribute the least to climate change, yet they are impacted the most. For example, people in low-income communities are disproportionately exposed to vehicle emissions, Muglia says. Through its Climate Change and Human Health Seed Grants program, Burroughs Wellcome funds research that aims to understand how various factors related to climate change and environmental chemicals contribute to premature births, associated with health vulnerabilities over the course of a person’s life—and map such hot spots.

“It’s very complex, the combinations of socio-economic environment, race, ethnicity and environmental exposure, whether that’s heat or toxic chemicals,” Muglia explains. “Disentangling those things really requires a very sophisticated, multidisciplinary team. That’s what we’ve put together to describe where these hotspots are and see how they correlate with different toxin exposure levels.”

In addition to mapping the risks, researchers are developing novel therapeutics that will be crucial to our armor arsenal, but we will have to be smarter at designing and using them. We will need more potent, better-working monoclonal antibodies. Instead of directly attacking a pathogen, we may have to learn to stimulate the immune system—training it to fight the disease-causing microbes on its own. And rather than indiscriminately killing all bacteria with broad-scope drugs, we would need more targeted medications. “Instead of wiping out the entire gut flora, we will need to come up with ways that kill harmful bacteria but not healthy ones,” Graves says. Training our immune systems to recognize and react to pathogens by way of vaccination will keep us ahead of our biological opponents, too. “Continued development of vaccines against infectious diseases is critical,” says Graves.

With all of the unpredictable events that lie ahead, it is difficult to foresee what achievements in public health will be reported at the end of the 21st century. Yet, technological advances, better modeling and pursuing bigger questions in science, along with education and working closely with communities will help overcome the challenges. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative displays an optimistic message on its website: “Is it possible to cure, prevent, or manage all diseases by the end of this century? We think so.” Cool shares the view of his employer—and believes that science can get us there. Just give it some time and a chance. “It’s a big, bold statement,” he says, “but the end of the century is a long way away.”Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

Stronger psychedelics that rewire the brain, with Doug Drysdale

Today's podcast episode features Doug Drysdale, CEO of Cybin, a company that is leading innovations in psilocybin, mushrooms that may help people with anxiety and depression.

A promising development in science in recent years has been the use technology to optimize something natural. One-upping nature's wisdom isn't easy. In many cases, we haven't - and maybe we can't - figure it out. But today's episode features a fascinating example: using tech to optimize psychedelic mushrooms.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

These mushrooms have been used for religious, spiritual and medicinal purposes for thousands of years, but only in the past several decades have scientists brought psychedelics into the lab to enhance them and maximize their therapeutic value.

Today’s podcast guest, Doug Drysdale, is doing important work to lead this effort. Drysdale is the CEO of a company called Cybin that has figured out how to make psilocybin more potent, so it can be administered in smaller doses without side effects.

The natural form of psilocybin has been studied increasingly in the realm of mental health. Taking doses of these mushrooms appears to help people with anxiety and depression by spurring the development of connections in the brain, an example of neuroplasticity. The process basically shifts the adult brain from being fairly rigid like dried clay into a malleable substance like warm wax - the state of change that's constantly underway in the developing brains of children.

Neuroplasticity in adults seems to unlock some of our default ways of of thinking, the habitual thought patterns that’ve been associated with various mental health problems. Some promising research suggests that psilocybin causes a reset of sorts. It makes way for new, healthier thought patterns.

So what is Drysdale’s secret weapon to bring even more therapeutic value to psilocybin? It’s a process called deuteration. It focuses on the hydrogen atoms in psilocybin. These atoms are very light and don’t stick very well to carbon, which is another atom in psilocybin. As a result, our bodies can easily breaks down the bonds between the hydrogen and carbon atoms. For many people, that means psilocybin gets cleared from the body too quickly, before it can have a therapeutic benefit.

In deuteration, scientists do something simple but ingenious: they replace the hydrogen atoms with a molecule called deuterium. It’s twice as heavy as hydrogen and forms tighter bonds with the carbon. Because these pairs are so rock-steady, they slow down the rate at which psilocybin is metabolized, so it has more sustained effects on our brains.

Cybin isn’t Drysdale’s first go around at this - far from it. He has over 30 years of experience in the healthcare sector. During this time he’s raised around $4 billion of both public and private capital, and has been named Ernst and Young Entrepreneur of the Year. Before Cybin, he was the founding CEO of a pharmaceutical company called Alvogen, leading it from inception to around $500 million in revenues, across 35 countries. Drysdale has also been the head of mergers and acquisitions at Actavis Group, leading 15 corporate acquisitions across three continents.

In this episode, Drysdale walks us through the promising research of his current company, Cybin, and the different therapies he’s developing for anxiety and depression based not just on psilocybin but another psychedelic compound found in plants called DMT. He explains how they seem to have such powerful effects on the brain, as well as the potential for psychedelics to eventually support other use cases, including helping us strive toward higher levels of well-being. He goes on to discuss his views on mindfulness and lifestyle factors - such as optimal nutrition - that could help bring out hte best in psychedelics.

Show links:

Doug Drysdale full bio

Doug Drysdale twitter

Cybin website

Cybin development pipeline

Cybin's promising phase 2 research on depression

Johns Hopkins psychedelics research and psilocybin research

Mets owner Steve Cohen invests in psychedelic therapies

Doug Drysdale, CEO of Cybin

How the body's immune resilience affects our health and lifespan

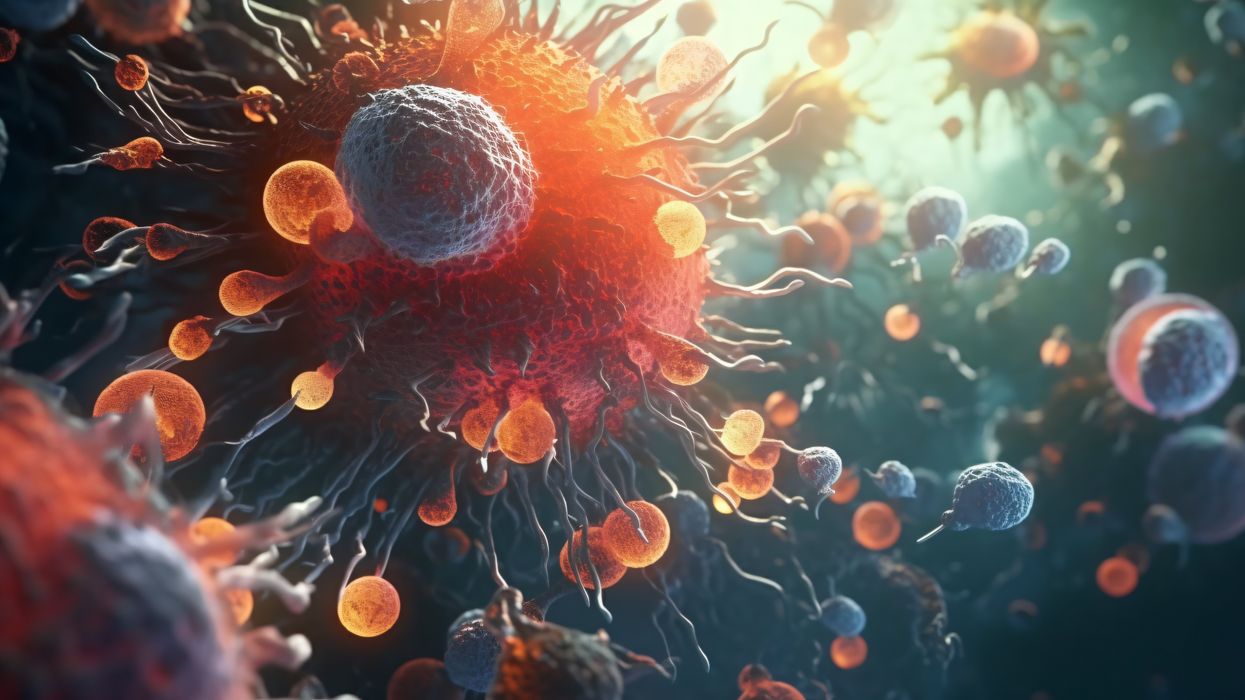

Immune cells battle an infection.

Story by Big Think

It is a mystery why humans manifest vast differences in lifespan, health, and susceptibility to infectious diseases. However, a team of international scientists has revealed that the capacity to resist or recover from infections and inflammation (a trait they call “immune resilience”) is one of the major contributors to these differences.

Immune resilience involves controlling inflammation and preserving or rapidly restoring immune activity at any age, explained Weijing He, a study co-author. He and his colleagues discovered that people with the highest level of immune resilience were more likely to live longer, resist infection and recurrence of skin cancer, and survive COVID and sepsis.

Measuring immune resilience

The researchers measured immune resilience in two ways. The first is based on the relative quantities of two types of immune cells, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. CD4+ T cells coordinate the immune system’s response to pathogens and are often used to measure immune health (with higher levels typically suggesting a stronger immune system). However, in 2021, the researchers found that a low level of CD8+ T cells (which are responsible for killing damaged or infected cells) is also an important indicator of immune health. In fact, patients with high levels of CD4+ T cells and low levels of CD8+ T cells during SARS-CoV-2 and HIV infection were the least likely to develop severe COVID and AIDS.

Individuals with optimal levels of immune resilience were more likely to live longer.

In the same 2021 study, the researchers identified a second measure of immune resilience that involves two gene expression signatures correlated with an infected person’s risk of death. One of the signatures was linked to a higher risk of death; it includes genes related to inflammation — an essential process for jumpstarting the immune system but one that can cause considerable damage if left unbridled. The other signature was linked to a greater chance of survival; it includes genes related to keeping inflammation in check. These genes help the immune system mount a balanced immune response during infection and taper down the response after the threat is gone. The researchers found that participants who expressed the optimal combination of genes lived longer.

Immune resilience and longevity

The researchers assessed levels of immune resilience in nearly 50,000 participants of different ages and with various types of challenges to their immune systems, including acute infections, chronic diseases, and cancers. Their evaluation demonstrated that individuals with optimal levels of immune resilience were more likely to live longer, resist HIV and influenza infections, resist recurrence of skin cancer after kidney transplant, survive COVID infection, and survive sepsis.

However, a person’s immune resilience fluctuates all the time. Study participants who had optimal immune resilience before common symptomatic viral infections like a cold or the flu experienced a shift in their gene expression to poor immune resilience within 48 hours of symptom onset. As these people recovered from their infection, many gradually returned to the more favorable gene expression levels they had before. However, nearly 30% who once had optimal immune resilience did not fully regain that survival-associated profile by the end of the cold and flu season, even though they had recovered from their illness.

Intriguingly, some people who are 90+ years old still have optimal immune resilience, suggesting that these individuals’ immune systems have an exceptional capacity to control inflammation and rapidly restore proper immune balance.

This could suggest that the recovery phase varies among people and diseases. For example, young female sex workers who had many clients and did not use condoms — and thus were repeatedly exposed to sexually transmitted pathogens — had very low immune resilience. However, most of the sex workers who began reducing their exposure to sexually transmitted pathogens by using condoms and decreasing their number of sex partners experienced an improvement in immune resilience over the next 10 years.

Immune resilience and aging

The researchers found that the proportion of people with optimal immune resilience tended to be highest among the young and lowest among the elderly. The researchers suggest that, as people age, they are exposed to increasingly more health conditions (acute infections, chronic diseases, cancers, etc.) which challenge their immune systems to undergo a “respond-and-recover” cycle. During the response phase, CD8+ T cells and inflammatory gene expression increase, and during the recovery phase, they go back down.

However, over a lifetime of repeated challenges, the immune system is slower to recover, altering a person’s immune resilience. Intriguingly, some people who are 90+ years old still have optimal immune resilience, suggesting that these individuals’ immune systems have an exceptional capacity to control inflammation and rapidly restore proper immune balance despite the many respond-and-recover cycles that their immune systems have faced.

Public health ramifications could be significant. Immune cell and gene expression profile assessments are relatively simple to conduct, and being able to determine a person’s immune resilience can help identify whether someone is at greater risk for developing diseases, how they will respond to treatment, and whether, as well as to what extent, they will recover.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.