The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

A Rare Disease Just "Messed with the Wrong Mother." Now She's Fighting to Beat It Once and For All.

Amber Freed and Maxwell near their home in Denver, Colorado.

Amber Freed felt she was the happiest mother on earth when she gave birth to twins in March 2017. But that euphoric feeling began to fade over the next few months, as she realized her son wasn't making the same developmental milestones as his sister. "I had a perfect benchmark because they were twins, and I saw that Maxwell was floppy—he didn't have muscle tone and couldn't hold his neck up," she recalls. At first doctors placated her with statements that boys sometimes develop slower than girls, but the difference was just too drastic. At 10 month old, Maxwell had never reached to grab a toy. In fact, he had never even used his hands.

Thinking that perhaps Maxwell couldn't see well, Freed took him to an ophthalmologist who was the first to confirm her worst fears. He didn't find Maxwell to have vision problems, but he thought there was something wrong with the boy's brain. He had seen similar cases before and they always turned out to be rare disorders, and always fatal. "Start preparing yourself for your child not to live," he had said.

Getting the diagnosis took months of painful, invasive procedures, as well as fighting with the health insurance to get the genetic testing approved. Finally, in June 2018, doctors at the Children's Hospital Colorado gave the Freeds their son's diagnosis—a genetic mutation so rare it didn't even have a name, just a bunch of letters jammed together into a word SLC6A1—same as the name of the mutated gene. The mutation, with only 40 cases known worldwide at the time, caused developmental disabilities, movement and speech disorders, and a debilitating form of epilepsy.

The doctors didn't know much about the disorder, but they said that Maxwell would also regress in his development when he turned three or four. They couldn't tell how long he would live. "Hopefully you would become an expert and educate us about it," they said, as they gave Freed a five-page paper on the SLC6A1 and told her to start calling scientists if she wanted to help her son in any way. When she Googled the name, nothing came up. She felt horrified. "Our disease was too rare to care."

Freed's husband, a 6'2'' college football player broke down in sobs and she realized that if anything could be done to help Maxwell, she'd have be the one to do it. "I understood that I had to fight like a mother," she says. "And a determined mother can do a lot of things."

The Freed family.

Courtesy Amber Freed

She quit her job as an equity analyst the day of the diagnosis and became a full-time SLC6A1 citizen scientist looking for researchers studying mutations of this gene. In the wee hours of the morning, she called scientists in Europe. As the day progressed, she called researchers on the East Coast, followed by the West in the afternoon. In the evening, she switched to Asia and Australia. She asked them the same question. "Can you help explain my gene and how do we fix it?"

Scientists need money to do research, so Freed launched Milestones for Maxwell fundraising campaign, and a SLC6A1 Connect patient advocacy nonprofit, dedicated to improving the lives of children and families battling this rare condition. And then it became clear that the mutation wasn't as rare as it seemed. As other parents began to discover her nonprofit, the number of known cases rose from 40 to 100, and later to 400, Freed says. "The disease is only rare until it messes with the wrong mother."

It took one mother to find another to start looking into what's happening inside Maxwell's brain. Freed came across Jeanne Paz, a Gladstone Institutes researcher who studies epilepsy with particular interest in absence or silent seizures—those that don't manifest by convulsions, but rather make patients absently stare into space—and that's one type of seizures Maxwell has. "It's like a brief period of silence in the brain during which the person doesn't pay attention to what's happening, and as soon as they come out of the seizure they are back to life," Paz explains. "It's like a pause button on consciousness." She was working to understand the underlying biology.

To understand how seizures begin, spread and stop, Paz uses optogenetics in mice. From words "genetic" and "optikós," which means visible in Greek, the optogenetics technique involves two steps. First, scientists introduce a light-sensitive gene into a specific brain cell type—for example into excitatory neurons that release glutamate, a neurotransmitter, which activates other cells in the brain. Then they implant a very thin optical fiber into the brain area where they forged these light-sensitive neurons. As they shine the light through the optical fiber, researchers can make excitatory neurons to release glutamate—or instead tell them to stop being active and "shut up". The ability to control what these neurons of interest do, quite literally sheds light onto where seizures start, how they propagate and what cells are involved in stopping them.

"Let's say a seizure started and we shine the light that reduces the activity of specific neurons," Paz explains. "If that stops the seizure, we know that activating those cells was necessary to maintain the seizure." Likewise, shutting down their activity will make the seizure stop.

Freed reached out to Paz in 2019 and the two women had an instant connection. They were both passionate about brain and seizures research, even if for different reasons. Freed asked Paz if she would study her son's seizures and Paz agreed.

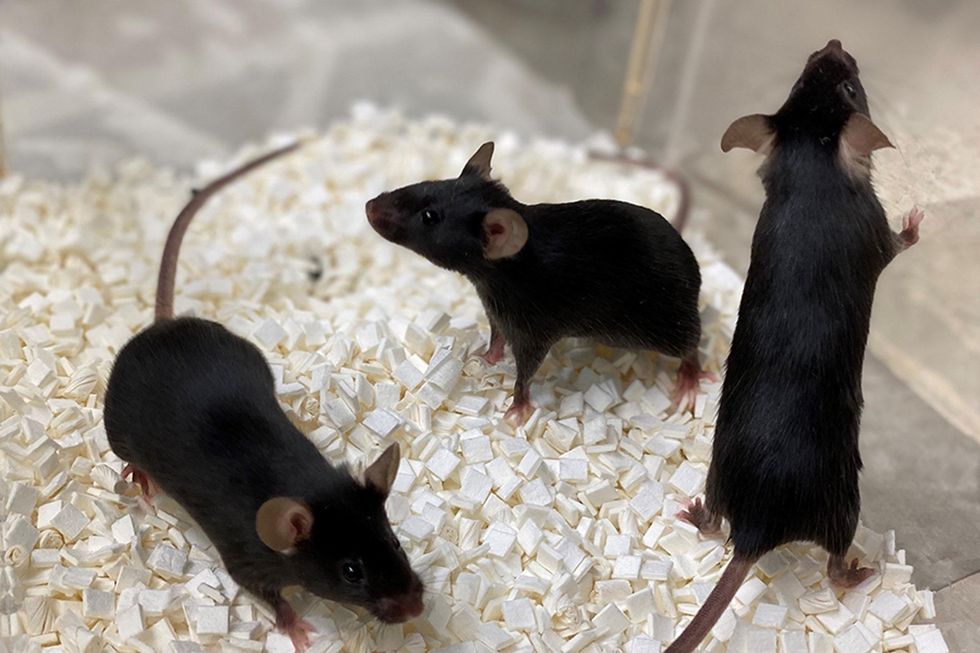

To do that, Paz needed mice that carried the SLC6A1 mutation, so Freed found a company in China that created them to specs. The company replaced a mouse SLC6A1 gene with a human mutated one and shipped them over to Paz's lab. "We call them Maxwell mice," Paz says, "and we are now implanting electrodes into them to see which brain regions generate seizures." That would help them understand what goes wrong and what brain cells are malfunctioning in the SLC6A1 mice—and help scientists better understand what might cause seizures in children.

Bred to carry SLC6A1 mutation, these "Maxwell mice" will help better understand this debilitating genetic disease. (These mice are from Vanderbilt University, where researchers are also studying SLC6A1.)

Courtesy Amber Freed

This information—along with other research Amber is funding in other institutions—will inform the development of a novel genetic treatment, in which scientists would deploy a harmless virus to deliver a healthy, working copy of the SLC6A1 gene into the mice brains. They would likely deliver the therapeutic via a spinal tap infusion, and if it works and doesn't produce side effects in mice, the human trials will follow.

In the meantime, Freed is raising money to fund other research of various stop-gap measures. On April 22, 2021, she updated her Milestone for Maxwell page with a post that her nonprofit is funding yet another effort. It is a trial at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, in which doctors will use an already FDA-approved drug, which was recently repurposed for the SLC6A1 condition to treat epilepsy in these children. "It will buy us time," Freed says—while the gene therapy effort progresses.

Freed is determined to beat SLC6A1 before it beats down her family. She hopes to put an end to this disease—and similar genetic diseases—once and for all. Her goal is not only to have scientists create a remedy, but also to add the mutation to a newborn screening panel. That way, children born with this condition in the future would receive gene therapy before they even leave the hospital.

"I don't want there to be another Maxwell Freed," she says, "and that's why I am fighting like a mother." The gene therapy trial still might be a few years away, but the Weill Cornell one aims to launch very soon—possibly around Mother's Day. This is yet another milestone for Maxwell, another baby step forward—and the best gift a mother can get.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

On May 13th, scientific and medical experts will discuss and answer questions about the vaccine for those under 16.

This virtual event convened leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about Covid-19 vaccines in kids and teens. Highlight video below.

DATE:

Thursday, May 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

Dr. H. Dele Davies, M.D., MHCM

Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean for Graduate Studies at the University of Nebraska Medical (UNMC). He is an internationally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases and a leader in community health.

Dr. Emily Oster, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics at Brown University. She is a best-selling author and parenting guru who has pioneered a method of assessing school safety.

Dr. Tina Q. Tan, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. She has been involved in several vaccine survey studies that examine the awareness, acceptance, barriers and utilization of recommended preventative vaccines.

Dr. Inci Yildirim, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc.

Associate Professor of Pediatrics (Infectious Disease); Medical Director, Transplant Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine; Associate Professor of Global Health, Yale Institute for Global Health. She is an investigator for the multi-institutional COVID-19 Prevention Network's (CoVPN) Moderna mRNA-1273 clinical trial for children 6 months to 12 years of age.

About the Event Series

This event is the second of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.