The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

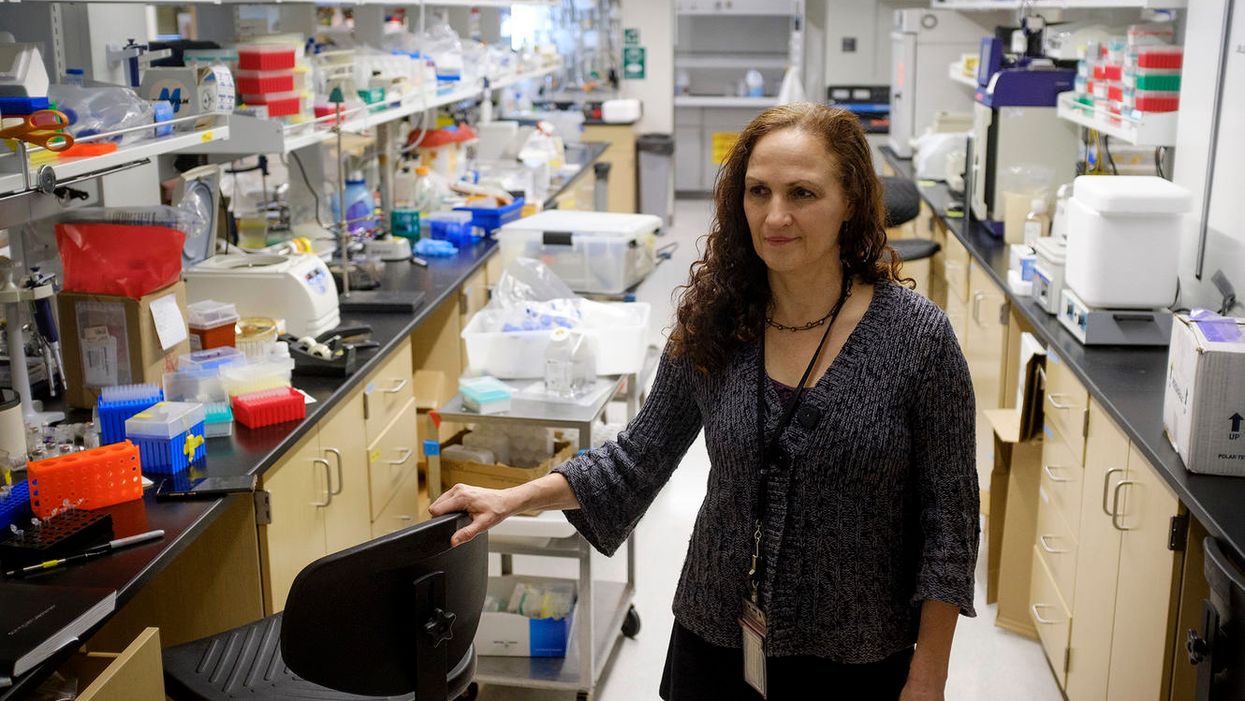

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

Scientists Envision a Universal Coronavirus Vaccine

Dr. Deborah Fuller, a professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine, in her lab.

With several companies progressing through Phase III clinical trials, the much-awaited coronavirus vaccines may finally become reality within a few months.

But some scientists question whether these vaccines will produce a strong and long-lasting immunity, especially if they aren't efficient at mobilizing T-cells, the body's defense soldiers.

"When I look at those vaccines there are pitfalls in every one of them," says Deborah Fuller, professor of microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine. "Some may induce only transient antibodies, some may not be very good at inducing T-cell responses, and others may not immunize the elderly very well."

Generally, vaccines work by introducing an antigen into the body—either a dead or attenuated pathogen that can't replicate, or parts of the pathogen or its proteins, which the body will recognize as foreign. The pathogens or its parts are usually discovered by cells that chew up the intruders and present them to the immune system fighters, B- and T-cells—like a trespasser's mug shot to the police. In response, B-cells make antibodies to neutralize the virus, and a specialized "crew" called memory B-cells will remember the antigen. Meanwhile, an army of various T-cells attacks the pathogens as well as the cells these pathogens already infected. Special helper T-cells help stimulate B-cells to secrete antibodies and activate cytotoxic T-cells that release chemicals called inflammatory cytokines that kill pathogens and cells they infected.

"Each of these components of the immune system are important and orchestrated to talk to each other," says professor Larry Corey, who studies vaccines and infectious disease at Fred Hutch, a non-profit scientific research organization. "They optimize the assault of the human immune system on the complexity of the viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic infections that live on our planet, to which we get exposed."

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify.

The current frontrunner vaccines aim to train our body to generate a sufficient amount of antibodies to neutralize the virus by shutting off its spike proteins before it enters our cells and begins to replicate. But a truly robust vaccine should also engender a strong response from T-cells, Fuller believes.

"Everyone focuses on the antibodies which block the virus, but it's not always 100 percent effective," she explains. "For example, if there are not enough titers or the antibody starts to wane, and the virus does get into the cells, the cells will become infected. At that point, the body needs to mount a robust T-cytotoxic response. The T-cells should find and recognize cells infected with the virus and eliminate these cells, and the virus with them."

Some of the frontrunner vaccine makers including Moderna, AstraZeneca and CanSino reported that they observed T-cell responses in their trials. Another company, BioNTech, based in Germany, also reported that their vaccine produced T-cell responses.

Fuller and her team are working on their own version of a coronavirus vaccine. In their recent study, the team managed to trigger a strong antibody and T-cell response in mice and primates. Moreover, the aging animals also produced a robust response, which would be important for the human elderly population.

But Fuller's team wants to engage T-cells further. She wants to try training T-cells to recognize not only SARV-CoV-2, but a range of different coronaviruses. Wild hosts, such as bats, carry many different types of coronaviruses, which may spill over onto humans, just like SARS, MERS and SARV-CoV-2 have. There are also four coronaviruses already endemic to humans. Cryptically named 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1, they were identified in the 1960s. And while they cause common colds and aren't considered particularly dangerous, the next coronavirus that jumps species may prove deadlier than the previous ones.

Despite their variety, coronaviruses share certain common proteins and other structural elements, Fuller explains, which the immune system can be trained to identify. "T-cells can recognize these shared sequences across multiple different types of coronaviruses," she explains, "so we have this vision for a universal coronavirus vaccine."

Paul Offit at Children's Hospitals in Philadelphia, who specializes in infectious diseases and vaccines, thinks it's a far shot at the moment. "I don't see that as something that is likely to happen, certainly not very soon," he says, adding that a universal flu vaccine has been tried for decades but is not available yet. We still don't know how the current frontrunner vaccines will perform. And until we know how efficient they are, wearing masks and keeping social distance are still important, he notes.

Corey says that while the universal coronavirus vaccine is not impossible, it is certainly not an easy feat. "It is a reasonably scientific hypothesis," he says, but one big challenge is that there are still many unknown coronaviruses so anticipating their structural elements is difficult. The structure of new viruses, particularly the recombinant ones that leap from wild hosts and carry bits and pieces of animal and human genetic material, can be hard to predict. "So whether you can make a vaccine that has universal T-cells to every coronavirus is also difficult to predict," Corey says. But, he adds, "I'm not being negative. I'm just saying that it's a formidable task."

Fuller is certainly up to the task and thinks it's worth the effort. "T-cells can cross-recognize different viruses within the same family," she says, so increasing their abilities to home in on a broader range of coronaviruses would help prevent future pandemics. "If that works, you're just going to take one [vaccine] and you'll have lifetime immunity," she says. "Not just against this coronavirus, but any future pandemic by a coronavirus."

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

New Tests Measure Your Body’s Biological Age, Offering a Glimpse into the Future of Health Care

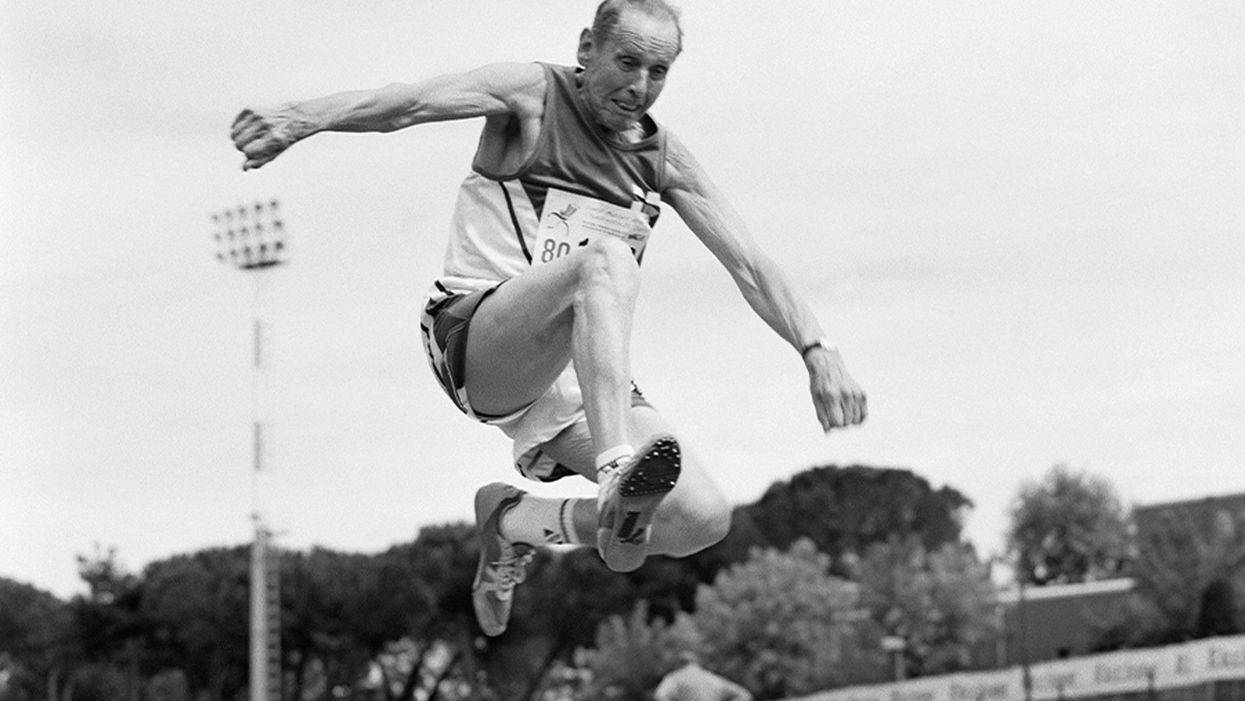

A senior long jumper competes in the 80-84-year-old age division at the 2007 World Masters Championships Stadia (track and field competition) at Riccione Stadium in Riccione, Italy on September 6, 2007. From the book project Racing Age.

What if a simple blood test revealed how fast you're aging, and this meant more to you and your insurance company than the number of candles on your birthday cake?

The question of why individuals thrive or decline has loomed large in 2020, with COVID-19 harming people of all ages, while leaving others asymptomatic. Meanwhile, scientists have produced new measures, called aging clocks, that attempt to predict mortality and may eventually affect how we perceive aging.

Take, for example, "senior" athletes who perform more like 50-year-olds. But people over 65 are lumped into one category, whether they are winning marathons or using a walker. Meanwhile, I'm entering "middle age," a label just as vague. It's frustrating to have a better grasp on the lifecycle of my phone than my own body.

That could change soon, due to clock technology. In 2013, UCLA biostatistician Steven Horvath took a new approach to an old carnival trick, guessing people's ages by looking at epigenetics: how chemical compounds in our cells turn genetic instructions on or off. Exercise, pollutants, and other aspects of lifestyle and environment can flip these switches, converting a skin cell into a hair cell, for example. Then, hair may sprout from your ears.

Horvath's epigenetic clock approximated age within just a few years; an above-average estimate suggested fast aging. This "basically changed everything," said Vadim Gladyshev, a Harvard geneticist, leading to more epigenetic clocks and, just since May, additional clocks of the heart, products of cell metabolism, and microbes in a person's mouth and gut.

Machine learning is fueling these discoveries. Scientists send algorithms hunting through jungles of health data for factors related to physical demise. "Nothing in [the aging] industry has progressed as much as biomarkers," said Alex Zhavoronkov, CEO of Deep Longevity, a pioneer in learning-based clocks.

Researchers told LeapsMag that this tech could help identify age-related vulnerabilities to diseases—including COVID-19—and protective drugs.

Clocking disease vulnerability

In July, Yale researcher Morgan Levine found people were more likely to be hospitalized and die from COVID-19 if their aging clocks were ticking ahead of their calendar years. This effect held regardless of pre-existing conditions.

The study used Levine's biological aging clock, called PhenoAge, which is more accurate than previous versions. To develop it, she looked at data on health indices over several decades, focusing on nine hallmarks of aging—such as inflammation—that correspond to when people die. Then she used AI to find which epigenetic patterns in blood samples were strongly associated with physical aging. The PhenoAge clock reads these patterns to predict biological age; mortality goes up 62 percent among the fastest agers.

The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention.

Because PhenoAge links chronic inflammation to aging and vulnerability, Levine proposed treating "inflammaging" to counter COVID-19.

Gladyshev reported similar findings, and Nir Barzilai, director of the Institute of Aging Research at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, agreed that biological age deserves greater focus. PhenoAge is an important innovation, he said, but most precise when measuring average age across large populations. Until clocks—including his blood protein version—account for differences in how individuals age, "Multi-morbidity is really the major biomarker" for a given person. Barzilai thinks individuals over 65 with two or more diseases are biologically older than their chronological age—about half the population in this study.

He believes COVID-19 efforts aren't taking stock of these differences. "The scientists are living in silos," he said, with many unaware aging has a biology that can be targeted.

The missed opportunities could be profound, especially for lower-income communities with disproportionately advanced aging. Barzilai has read eight different observational studies finding decreased COVID-19 severity among people taking metformin, the diabetes drug, which is believed to slow down the major hallmarks of biological aging, such as inflammation. Once a vaccine is identified, biologically older people could supplement it with metformin, but the medical establishment requires lengthy clinical trials. "The conservatism is taking over in days of war," Barzilai said.

Drug benefits on time

Clocks, once validated, could gauge drug effectiveness against age-related diseases quicker and cheaper than trials that track health outcomes over many years, expediting FDA approval of such therapies. For this to happen, though, the FDA must see evidence that rewinding clocks or improving related biomarkers leads to clinical benefits for patients. Researchers believe that clinical applications for at least some of these clocks are five to 10 years away.

Progress was made in last year's TRIIM trial, run by immunologist Gregory Fahy at Stanford Medical Center. People in their 50s took growth hormone, metformin and another diabetes drug, dehydroepiandrosterone, for 12 months. The cocktail, aimed at restoring immune function, reversed age by an average of 2.5 years, according to an epigenetic clock measurement taken before and after the intervention. Don't quit your gym just yet; TRIIM included just nine Caucasian men. A follow-up with 85 diverse participants begins next month.

But even group averages of epigenetic measures can be questionable, explained Willard Freeman, a researcher with the Reynolds Oklahoma Center on Aging. Consider this odd finding: heroin addicts tend to have younger epigenetic ages. "With the exception of Keith Richards, I don't think heroin is a great way to live a long healthy life," Freeman said.

Such confounders reveal that scientists—and AI—are still struggling to unearth the roots of aging. Do clocks simply reflect damage, mirrors to show who's the frailest of them all? Or do they programmatically drive aging? The answer involves vast complexity, like trying to deduce the direct causes of a 17-car pileup on a potholed road in foggy conditions. Except, instead of 17 cars, it's millions of epigenetic sites and thousands of potential genes, RNA molecules and blood proteins acting on aging and each other.

Because the various measures—epigenetics, microbes, etc.—capture distinct aging dimensions, an important goal is unifying them into one "mosaic of biological ages," as Levine called it. Gladyshev said more datasets are needed. Just yesterday, though, Zhavoronkov launched Deep Longevity's groundbreaking composite of metrics to consumers – something that was previously available only to clinicians. The iPhone app allows users to upload their own samples and tracks aging on multiple levels – epigenetic, behavioral, microbiome, and more. It even includes a deep psychological clock asking if people feel as old as they are. Perhaps Twain's adage about mind over matter is evidence-backed.

Zhavoronkov appeared youthful in our Zoom interview, but admitted self-testing shows an advanced age because "I do not sleep"; indeed, he'd scheduled me at midnight Hong Kong time. Perhaps explaining his insomnia, he fears economic collapse if age-related diseases cost the global economy over $30 trillion by 2030. Rather than seeking eternal life, researchers like Zhavoronkov aim to increase health span: fully living our final decades without excess pain and hospital bills.

It's also a lucrative sales pitch to 7.8 billion aging humans.

Get your bio age

Levine, the Yale scientist, has partnered with Elysium Health to sell Index, an epigenetic measure launched in late 2019, direct to consumers, using their saliva samples. Elysium will roll out additional measures as research progresses, starting with an assessment of how fast someone is accumulating cells that no longer divide. "The more measures to capture specific processes, the more we can actually understand what's unique for an individual," Levine said.

Another company, InsideTracker, with an advisory board headlined by Harvard's David Sinclair, eschews the quirkiness of epigenetics. Its new InnerAge 2.0 test, announced this month, analyzes 18 blood biomarkers associated with longevity.

"You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them."

Because aging isn't considered a disease, consumer aging tests don't require FDA approval, and some researchers are skeptical of their use in the near future. "I'm on the fence as to whether these things are ready to be rolled out," said Freeman, the Oklahoma researcher. "We need to do our traditional experimental study design to [be] confident they're actually useful."

Then, 50-year-olds who are biologically 45 may wait five years for their first colonoscopy, Barzilai said. Despite some forerunners, clinical applications for individuals are mostly prospective, yet I was intrigued. Could these clocks reveal if I'm following the footsteps of the super-agers? Or will I rack up the hospital bills of Zhavoronkov's nightmares?

I sent my blood for testing with InsideTracker. Fearing the worst—an InnerAge accelerated by a couple of decades—I asked thought leaders where this technology is headed.

Insurance 2030

With continued advances, by 2030 you'll learn your biological age with a glance at your wristwatch. You won't be the only monitor; your insurance company may send an alert if your age goes too high, threatening lost rewards.

If this seems implausible, consider that life insurer John Hancock already tracks a VitalityAge. With Obamacare incentivizing companies to engage policyholders in improving health, many are dangling rewards for fitness. BlueCross BlueShield covers 25 percent of InsideTracker's cost, and UnitedHealthcare offers a suite of such programs, including "missions" for policyholders to lower their Rally age. "People underestimate the amount of time they're sedentary," said Michael Bess, vice president of healthcare strategies. "So having this technology to drive positive reinforcement is just another way to encourage healthy behavior."

It's unclear if these programs will close health gaps, or simply attract customers already prioritizing fitness. And insurers could raise your premium if you don't measure up. Obamacare forbids discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, but will accelerated age qualify for this protection?

Liz McFall, a sociologist at the University of Edinburgh, thinks the answer depends on whether we view aging as controllable. "You can imagine payers clamoring to charge people for costs with a kind of personal responsibility to them," she said.

That outcome troubles Mark Rothstein, director of the Institute of Bioethics at the University of Louisville. "For those living with air pollution and unsafe water, in food deserts and where you can't safely exercise, then [insurers] take the results in terms of biological stressors, now you're adding insult to injury," he said.

Government could subsidize aging clocks and interventions for older people with fewer resources for controlling their health—and the greatest room for improving their epigenetic age. Rothstein supports that policy, but said, "I don't see it happening."

Bio age working for you

2030 again. A job posting seeks a "go-getter," so you attach a doctor's note to your resume proving you're ten years younger than your chronological age.

This prospect intrigued Cathy Ventrell-Monsees, senior advisor at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Any marker other than age is a step forward," she said. "Age simply doesn't determine any kind of cognitive or physical ability."

What if the assessment isn't voluntary? Armed with AI, future employers could surveil a candidate's biological age from their head-shot. Haut.ai is already marketing an uncannily accurate PhotoAgeClock. Its CEO, Anastasia Georgievskaya, noted this tech's promise in other contexts; it could help people literally see the connection between healthier lifestyles and looking young and attractive. "The images keep people quite engaged," she told me.

Updating laws could minimize drawbacks. Employers are already prohibited from using genetic information to discriminate (think 23andMe). The ban could be extended to epigenetics. "I would imagine biomarkers for aging go a similar path as genetic nondiscrimination," said McFall, the sociologist.

Will we use aging clocks to screen candidates for the highest office? Barzilai, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine researcher, believes Trump and Biden have similar biological ages. But one of Barzilai's factors, BMI, is warped by Trump miraculously getting taller. "Usually people get shorter with age," Barzilai said. "His weight has been increasing, but his BMI stays the same."

As for my bio age? InnerAge suggested I'm four years younger—and by boosting my iron levels, the program suggests, I could be younger still.

We need standards for these tests, and customers must understand their shortcomings. With such transparency, though, the benefits could be compelling. In March, Theresa Brown, a 44-year-old from Kansas, learned her InnerAge was 57.2. She followed InsideTracker's recommendations, including regular intermittent fasting. Retested five months later, her age had dropped to 34.1. "It's not that I guaranteed another 10 or 20 years to my life. It's that it encourages me. Whether I really am or not, I just feel younger. I'll take that."

Which leads back to Zhavoronkov's psychological clock. Perhaps lowering our InnerAges can be the self-fulfilling prophesy that helps Theresa and me age like the super-athletes who thrive longer than expected. McFall noted the power of simple, sufficiently credible goals for encouraging better health. Think 10,000 steps per day, she said.

Want to be 34 again? Just do it.

Yet, many people's budgets just don't allow gym memberships, nutritious groceries, or futuristic aging clocks. Bill Gates cautioned we overestimate progress in the next two years, while underestimating the next ten. Policies should ensure that age testing and interventions are distributed fairly.

"Within the next 5 to 10 years," said Gladyshev, "there will be drugs and lifestyle changes which could actually increase lifespan or healthspan for the entire population."