Coronavirus Risk Calculators: What You Need to Know

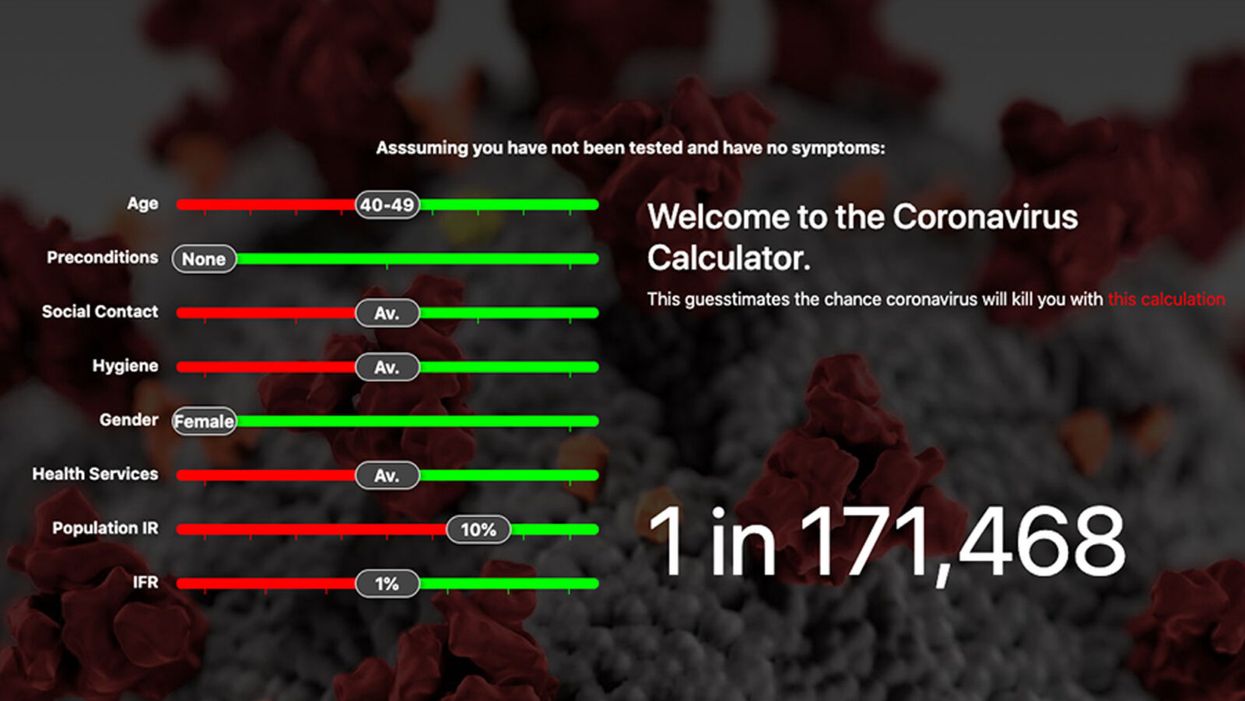

A screenshot of one coronavirus risk calculator.

People in my family seem to develop every ailment in the world, including feline distemper and Dutch elm disease, so I naturally put fingers to keyboard when I discovered that COVID-19 risk calculators now exist.

"It's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk."

But the results – based on my answers to questions -- are bewildering.

A British risk calculator developed by the Nexoid software company declared I have a 5 percent, or 1 in 20, chance of developing COVID-19 and less than 1 percent risk of dying if I get it. Um, great, I think? Meanwhile, 19 and Me, a risk calculator created by data scientists, says my risk of infection is 0.01 percent per week, or 1 in 10,000, and it gave me a risk score of 44 out of 100.

Confused? Join the club. But it's actually possible to interpret numbers like these and put them to use. Here are five tips about using coronavirus risk calculators:

1. Make Sure the Calculator Is Designed For You

Not every COVID-19 risk calculator is designed to be used by the general public. Cleveland Clinic's risk calculator, for example, is only a tool for medical professionals, not sick people or the "worried well," said Dr. Lara Jehi, Cleveland Clinic's chief research information officer.

Unfortunately, the risk calculator's web page fails to explicitly identify its target audience. But there are hints that it's not for lay people such as its references to "platelets" and "chlorides."

The 19 and Me or the Nexoid risk calculators, in contrast, are both designed for use by everyone, as is a risk calculator developed by Emory University.

2. Take a Look at the Calculator's Privacy Policy

COVID-19 risk calculators ask for a lot of personal information. The Nexoid calculator, for example, wanted to know my age, weight, drug and alcohol history, pre-existing conditions, blood type and more. It even asked me about the prescription drugs I take.

It's wise to check the privacy policy and be cautious about providing an email address or other personal information. Nexoid's policy says it provides the information it gathers to researchers but it doesn't release IP addresses, which can reveal your location in certain circumstances.

John-Arne Skolbekken, a professor and risk specialist at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, entered his own data in the Nexoid calculator after being contacted by LeapsMag for comment. He noted that the calculator, among other things, asks for information about use of recreational drugs that could be illegal in some places. "I have given away some of my personal data to a company that I can hope will not misuse them," he said. "Let's hope they are trustworthy."

The 19 and Me calculator, by contrast, doesn't gather any data from users, said Cindy Hu, data scientist at Mathematica, which created it. "As soon as the window is closed, that data is gone and not captured."

The Emory University risk calculator, meanwhile, has a long privacy policy that states "the information we collect during your assessment will not be correlated with contact information if you provide it." However, it says personal information can be shared with third parties.

3. Keep an Eye on Time Horizons

Let's say a risk calculator says you have a 1 percent risk of infection. That's fairly low if we're talking about this year as a whole, but it's quite worrisome if the risk percentage refers to today and jumps by 1 percent each day going forward. That's why it's helpful to know exactly what the numbers mean in terms of time.

Unfortunately, this information isn't always readily available. You may have to dig around for it or contact a risk calculator's developers for more information. The 19 and Me calculator's risk percentages refer to this current week based on your behavior this week, Hu said. The Nexoid calculator, by contrast, has an "infinite timeline" that assumes no vaccine is developed, said Jonathon Grantham, the company's managing director. But your results will vary over time since the calculator's developers adjust it to reflect new data.

When you use a risk calculator, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

4. Focus on the Big Picture

The Nexoid calculator gave me numbers of 5 percent (getting COVID-19) and 99.309 percent (surviving it). It even provided betting odds for gambling types: The odds are in favor of me not getting infected (19-to-1) and not dying if I get infected (144-to-1).

However, Grantham told me that these numbers "are not the whole story." Instead, he said, "it's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk." Risk bands refer to a segmentation of people into five categories, from lowest to highest risk, according to how a person's result sits relative to the whole dataset.

The Nexoid calculator says I'm in the "lowest risk band" for getting COVID-19, and a "high risk band" for dying of it if I get it. That suggests I'd better stay in the lowest-risk category because my pre-existing risk factors could spell trouble for my survival if I get infected.

Michael J. Pencina, a professor and biostatistician at Duke University School of Medicine, agreed that focusing on your general risk level is better than focusing on numbers. When you use a risk calculator, he said, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

The 19 and Me calculator, meanwhile, put my risk at 44 out of 100. Hu said that a score of 50 represents the typical person's risk of developing serious consequences from another disease – the flu.

5. Remember to Take Action

Hu, who helped develop the 19 and Me risk calculator, said it's best to use it to "understand the relative impact of different behaviors." As she noted, the calculator is designed to allow users to plug in different answers about their behavior and immediately see how their risk levels change.

This information can help us figure out if we should change the way we approach the world by, say, washing our hands more or avoiding more personal encounters.

"Estimation of risk is only one part of prevention," Pencina said. "The other is risk factors and our ability to reduce them." In other words, odds, percentages and risk bands can be revealing, but it's what we do to change them that matters.

Podcast: The Science of Recharging Your Energy with Sara Mednick

For today's podcast episode, Leaps.org talks with Sara Mednick, author of The Power of the Downstate, a book about the science of relaxation - why it's so important, the best ways to get more of it, and the time of day when our bodies are biologically suited to enjoy it the most.

If you’re like me, you may have a case of email apnea, where you stop taking restful breaths when you open a work email. Or maybe you’re in the habit of shining blue light into your eyes long after sunset through your phone. Many of us are doing all kinds of things throughout the day that put us in a constant state of fight or flight arousal, with long-term impacts on health, productivity and happiness.

My guest for today’s episode is Sara Mednick, author of The Power of the Downstate, a book about the science of relaxation – why it’s so important, the best ways to go about getting more of it, and the time of day when our bodies are biologically suited to enjoy it the most. As a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California, Irvine, Mednick has a great scientific background on this topic. After getting her PhD at Harvard, she filled her sleep lab with 7 bedrooms, and this is where she is federally funded to study people sleeping around the clock, with her research published in top journals such as Nature Neuroscience. She received the Office Naval Research Young Investigator Award in 2015, and her previous book, Take a Nap! Change Your Life was based on her groundbreaking research on the benefits of napping.

In our conversation, we talk about how work and society make it tough to get stimulation like food and exercise in ways that support our circadian rhythms, and there just as many obstacles to getting sleep and restoration like our ancestors enjoyed for 99 percent of human history. Sara shares some fascinating ways to get around these challenges, as well as her insights about the importance of exposure to daylight and nature vs nurture when it comes to whether you’re a night owl or an early bird. And we talk about how things could change with work and lifestyles to make it easier to live in accordance with our biological rhythms.

Show notes

3:10 – The definition of “upstates” and “downstates”

5:50 – The power of 6 slow, deep breaths per minute to balance the nervous system

9:05 – Watching out for mouth breathing and email apnea

13:30 – Different ways of breathing for different goals

16:35 – Body rhythms – what is heart rate variability and why is it so important?

21:05 – Are you naturally a morning or night person? Nature vs nurture

27:10 – The perfect storm that gets in the way of following our circadian rhythms

29:15 – The evolution of our pre-bedtime downstates – why it's important to check in with your cave mates

30:10 – The culture shift needed for more people to follow their circadian rhythms and improve their health

35:10 – Employers and communities can build downstates into daily work and life

38:15 – Choosing how we react to the world

41:00 – Being smarter about peak performance

45:09 – The science of pacing yourself for long-term productivity

49:42 – The science of light exposure for circadian rhythms

52:20 – Where to learn more about Sara Mednick’s research and writing

Links:

Sara Mednick’s website https://www.saramednick.com/ and her Twitter

Mednick’s recent book - The Power of the Downstate

Mednick’s book on the benefits of napping - Take a Nap! Change Your Life

The blue light blocking glasses recommended in Mednick’s book https://www.amazon.com/dp/B019C3O2UE?psc=1&ref=ppx_yo2ov_dt_b_product_details

An app for measuring heart rate variability - Elite HRV app https://elitehrv.com/

Thorne take-home Melatonin test

Podcast: The Friday Five weekly roundup in health research

Researchers are making progress on a vaccine for Lyme disease, sex differences in cancer, new research on reducing your risk of dementia with leisure activities, and more in this week's Friday Five

The Friday Five covers five stories in health research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Covered in this week's Friday Five:

- Sex differences in cancer

- Promising research on a vaccine for Lyme disease

- Using a super material for brain-like devices

- Measuring your immunity to Covid

- Reducing dementia risk with leisure activities