Coronavirus Risk Calculators: What You Need to Know

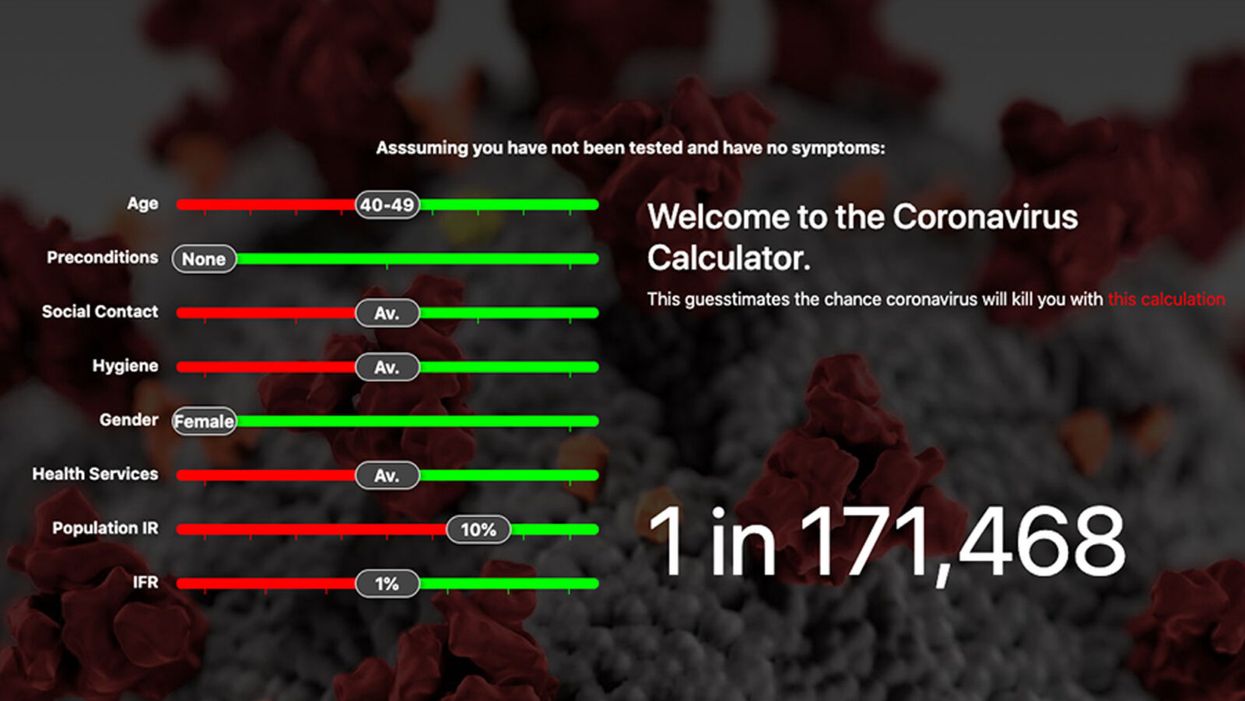

A screenshot of one coronavirus risk calculator.

People in my family seem to develop every ailment in the world, including feline distemper and Dutch elm disease, so I naturally put fingers to keyboard when I discovered that COVID-19 risk calculators now exist.

"It's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk."

But the results – based on my answers to questions -- are bewildering.

A British risk calculator developed by the Nexoid software company declared I have a 5 percent, or 1 in 20, chance of developing COVID-19 and less than 1 percent risk of dying if I get it. Um, great, I think? Meanwhile, 19 and Me, a risk calculator created by data scientists, says my risk of infection is 0.01 percent per week, or 1 in 10,000, and it gave me a risk score of 44 out of 100.

Confused? Join the club. But it's actually possible to interpret numbers like these and put them to use. Here are five tips about using coronavirus risk calculators:

1. Make Sure the Calculator Is Designed For You

Not every COVID-19 risk calculator is designed to be used by the general public. Cleveland Clinic's risk calculator, for example, is only a tool for medical professionals, not sick people or the "worried well," said Dr. Lara Jehi, Cleveland Clinic's chief research information officer.

Unfortunately, the risk calculator's web page fails to explicitly identify its target audience. But there are hints that it's not for lay people such as its references to "platelets" and "chlorides."

The 19 and Me or the Nexoid risk calculators, in contrast, are both designed for use by everyone, as is a risk calculator developed by Emory University.

2. Take a Look at the Calculator's Privacy Policy

COVID-19 risk calculators ask for a lot of personal information. The Nexoid calculator, for example, wanted to know my age, weight, drug and alcohol history, pre-existing conditions, blood type and more. It even asked me about the prescription drugs I take.

It's wise to check the privacy policy and be cautious about providing an email address or other personal information. Nexoid's policy says it provides the information it gathers to researchers but it doesn't release IP addresses, which can reveal your location in certain circumstances.

John-Arne Skolbekken, a professor and risk specialist at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, entered his own data in the Nexoid calculator after being contacted by LeapsMag for comment. He noted that the calculator, among other things, asks for information about use of recreational drugs that could be illegal in some places. "I have given away some of my personal data to a company that I can hope will not misuse them," he said. "Let's hope they are trustworthy."

The 19 and Me calculator, by contrast, doesn't gather any data from users, said Cindy Hu, data scientist at Mathematica, which created it. "As soon as the window is closed, that data is gone and not captured."

The Emory University risk calculator, meanwhile, has a long privacy policy that states "the information we collect during your assessment will not be correlated with contact information if you provide it." However, it says personal information can be shared with third parties.

3. Keep an Eye on Time Horizons

Let's say a risk calculator says you have a 1 percent risk of infection. That's fairly low if we're talking about this year as a whole, but it's quite worrisome if the risk percentage refers to today and jumps by 1 percent each day going forward. That's why it's helpful to know exactly what the numbers mean in terms of time.

Unfortunately, this information isn't always readily available. You may have to dig around for it or contact a risk calculator's developers for more information. The 19 and Me calculator's risk percentages refer to this current week based on your behavior this week, Hu said. The Nexoid calculator, by contrast, has an "infinite timeline" that assumes no vaccine is developed, said Jonathon Grantham, the company's managing director. But your results will vary over time since the calculator's developers adjust it to reflect new data.

When you use a risk calculator, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

4. Focus on the Big Picture

The Nexoid calculator gave me numbers of 5 percent (getting COVID-19) and 99.309 percent (surviving it). It even provided betting odds for gambling types: The odds are in favor of me not getting infected (19-to-1) and not dying if I get infected (144-to-1).

However, Grantham told me that these numbers "are not the whole story." Instead, he said, "it's best to look at your risk band. This will give you a more useful insight into your personal risk." Risk bands refer to a segmentation of people into five categories, from lowest to highest risk, according to how a person's result sits relative to the whole dataset.

The Nexoid calculator says I'm in the "lowest risk band" for getting COVID-19, and a "high risk band" for dying of it if I get it. That suggests I'd better stay in the lowest-risk category because my pre-existing risk factors could spell trouble for my survival if I get infected.

Michael J. Pencina, a professor and biostatistician at Duke University School of Medicine, agreed that focusing on your general risk level is better than focusing on numbers. When you use a risk calculator, he said, focus on this question: "How does your risk compare to the risk of an 'average' person?"

The 19 and Me calculator, meanwhile, put my risk at 44 out of 100. Hu said that a score of 50 represents the typical person's risk of developing serious consequences from another disease – the flu.

5. Remember to Take Action

Hu, who helped develop the 19 and Me risk calculator, said it's best to use it to "understand the relative impact of different behaviors." As she noted, the calculator is designed to allow users to plug in different answers about their behavior and immediately see how their risk levels change.

This information can help us figure out if we should change the way we approach the world by, say, washing our hands more or avoiding more personal encounters.

"Estimation of risk is only one part of prevention," Pencina said. "The other is risk factors and our ability to reduce them." In other words, odds, percentages and risk bands can be revealing, but it's what we do to change them that matters.

This man spent over 70 years in an iron lung. What he was able to accomplish is amazing.

Paul Alexander spent more than 70 years confined to an iron lung after a polio infection left him paralyzed at age 6. Here, Alexander uses a mirror attached to the top of his iron lung to view his surroundings.

It’s a sight we don’t normally see these days: A man lying prone in a big, metal tube with his head sticking out of one end. But it wasn’t so long ago that this sight was unfortunately much more common.

In the first half of the 20th century, tens of thousands of people each year were infected by polio—a highly contagious virus that attacks nerves in the spinal cord and brainstem. Many people survived polio, but a small percentage of people who did were left permanently paralyzed from the virus, requiring support to help them breathe. This support, known as an “iron lung,” manually pulled oxygen in and out of a person’s lungs by changing the pressure inside the machine.

Paul Alexander was one of several thousand who were infected and paralyzed by polio in 1952. That year, a polio epidemic swept the United States, forcing businesses to close and polio wards in hospitals all over the country to fill up with sick children. When Paul caught polio in the summer of 1952, doctors urged his parents to let him rest and recover at home, since the hospital in his home suburb of Dallas, Texas was already overrun with polio patients.

Paul rested in bed for a few days with aching limbs and a fever. But his condition quickly got worse. Within a week, Paul could no longer speak or swallow, and his parents rushed him to the local hospital where the doctors performed an emergency procedure to help him breathe. Paul woke from the surgery three days later, and found himself unable to move and lying inside an iron lung in the polio ward, surrounded by rows of other paralyzed children.

But against all odds, Paul lived. And with help from a physical therapist, Paul was able to thrive—sometimes for small periods outside the iron lung.

The way Paul did this was to practice glossopharyngeal breathing (or as Paul called it, “frog breathing”), where he would trap air in his mouth and force it down his throat and into his lungs by flattening his tongue. This breathing technique, taught to him by his physical therapist, would allow Paul to leave the iron lung for increasing periods of time.

With help from his iron lung (and for small periods of time without it), Paul managed to live a full, happy, and sometimes record-breaking life. At 21, Paul became the first person in Dallas, Texas to graduate high school without attending class in person, owing his success to memorization rather than taking notes. After high school, Paul received a scholarship to Southern Methodist University and pursued his dream of becoming a trial lawyer and successfully represented clients in court.

Throughout his long life, Paul was also able to fly on a plane, visit the beach, adopt a dog, fall in love, and write a memoir using a plastic stick to tap out a draft on a keyboard. In recent years, Paul joined TikTok and became a viral sensation with more than 330,000 followers. In one of his first videos, Paul advocated for vaccination and warned against another polio epidemic.

Paul was reportedly hospitalized with COVID-19 at the end of February and died on March 11th, 2024. He currently holds the Guiness World Record for longest survival inside an iron lung—71 years.

Polio thankfully no longer circulates in the United States, or in most of the world, thanks to vaccines. But Paul continues to serve as a reminder of the importance of vaccination—and the power of the human spirit.

““I’ve got some big dreams. I’m not going to accept from anybody their limitations,” he said in a 2022 interview with CNN. “My life is incredible.”

When doctors couldn’t stop her daughter’s seizures, this mom earned a PhD and found a treatment herself.

Savannah Salazar (left) and her mother, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar, who earned a PhD in neurobiology in the quest for a treatment of her daughter's seizure disorder.

Twenty-eight years ago, Tracy Dixon-Salazaar woke to the sound of her daughter, two-year-old Savannah, in the midst of a medical emergency.

“I entered [Savannah’s room] to see her tiny little body jerking about violently in her bed,” Tracy said in an interview. “I thought she was choking.” When she and her husband frantically called 911, the paramedic told them it was likely that Savannah had had a seizure—a term neither Tracy nor her husband had ever heard before.

Over the next several years, Savannah’s seizures continued and worsened. By age five Savannah was having seizures dozens of times each day, and her parents noticed significant developmental delays. Savannah was unable to use the restroom and functioned more like a toddler than a five-year-old.

Doctors were mystified: Tracy and her husband had no family history of seizures, and there was no event—such as an injury or infection—that could have caused them. Doctors were also confused as to why Savannah’s seizures were happening so frequently despite trying different seizure medications.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Savannah with Lennox-Gaustaut Syndrome, or LGS, an epilepsy disorder with no cure and a poor prognosis. People with LGS are often resistant to several kinds of anti-seizure medications, and often suffer from developmental delays and behavioral problems. People with LGS also have a higher chance of injury as well as a higher chance of sudden unexpected death (SUDEP) due to the frequent seizures. In about 70 percent of cases, LGS has an identifiable cause such as a brain injury or genetic syndrome. In about 30 percent of cases, however, the cause is unknown.

Watching her daughter struggle through repeated seizures was devastating to Tracy and the rest of the family.

“This disease, it comes into your life. It’s uninvited. It’s unannounced and it takes over every aspect of your daily life,” said Tracy in an interview with Today.com. “Plus it’s attacking the thing that is most precious to you—your kid.”

Desperate to find some answers, Tracy began combing the medical literature for information about epilepsy and LGS. She enrolled in college courses to better understand the papers she was reading.

“Ironically, I thought I needed to go to college to take English classes to understand these papers—but soon learned it wasn’t English classes I needed, It was science,” Tracy said. When she took her first college science course, Tracy says, she “fell in love with the subject.”

Tracy was now a caregiver to Savannah, who continued to have hundreds of seizures a month, as well as a full-time student, studying late into the night and while her kids were at school, using classwork as “an outlet for the pain.”

“I couldn’t help my daughter,” Tracy said. “Studying was something I could do.”

Twelve years later, Tracy had earned a PhD in neurobiology.

After her post-doctoral training, Tracy started working at a lab that explored the genetics of epilepsy. Savannah’s doctors hadn’t found a genetic cause for her seizures, so Tracy decided to sequence her genome again to check for other abnormalities—and what she found was life-changing.

Tracy discovered that Savannah had a calcium channel mutation, meaning that too much calcium was passing through Savannah’s neural pathways, leading to seizures. The information made sense to Tracy: Anti-seizure medications often leech calcium from a person’s bones. When doctors had prescribed Savannah calcium supplements in the past to counteract these effects, her seizures had gotten worse every time she took the medication. Tracy took her discovery to Savannah’s doctor, who agreed to prescribe her a calcium blocker.

The change in Savannah was almost immediate.

Within two weeks, Savannah’s seizures had decreased by 95 percent. Once on a daily seven-drug regimen, she was soon weaned to just four, and then three. Amazingly, Tracy started to notice changes in Savannah’s personality and development, too.

“She just exploded in her personality and her talking and her walking and her potty training and oh my gosh she is just so sassy,” Tracy said in an interview.

Since starting the calcium blocker eleven years ago, Savannah has continued to make enormous strides. Though still unable to read or write, Savannah enjoys puzzles and social media. She’s “obsessed” with boys, says Tracy. And while Tracy suspects she’ll never be able to live independently, she and her daughter can now share more “normal” moments—something she never anticipated at the start of Savannah’s journey with LGS. While preparing for an event, Savannah helped Tracy get ready.

“We picked out a dress and it was the first time in our lives that we did something normal as a mother and a daughter,” she said. “It was pretty cool.”