Can an “old school” vaccine address global inequities in Covid-19 vaccination?

Scientists at Baylor College of Medicine developed a vaccine called Corbevax that, unlike mRNA vaccines, can be mass produced using technology already in place in low- and middle-income countries. It's now being administered in India to children aged 12-14.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began invading the world in late 2019, Peter Hotez and Maria Elena Bottazzi set out to create a low-cost vaccine that would help inoculate populations in low- and middle-income countries. The scientists, with their prior experience of developing inexpensive vaccines for the world’s poor, had anticipated that the global rollout of Covid-19 jabs would be marked with several inequities. They wanted to create a patent-free vaccine to bridge this gap, but the U.S. government did not seem impressed, forcing the researchers to turn to private philanthropies for funds.

Hotez and Bottazzi, both scientists at the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development at Baylor College of Medicine, raised about $9 million in private funds. Meanwhile, the U.S. government’s contribution stood at $400,000.

“That was a very tough time early on in the pandemic, you know, trying to do the work and raise the money for it at the same time,” says Hotez, who was nominated in February for a Nobel Peace Prize with Bottazzi for their COVID-19 vaccine. He adds that at the beginning of the pandemic, governments emphasized speed, innovation and rapidly immunizing populations in North America and Europe with little consideration for poorer countries. “We knew this [vaccine] was going to be the answer to global vaccine inequality, but I just wish the policymakers had felt the same,” says Hotez.

Over the past two years, the world has witnessed 488 million COVID-19 infections and over 61 million deaths. Over 11 billion vaccine doses have been administered worldwide; however, the global rollout of COVID-19 vaccines is marked with alarming socio-economic inequities. For instance, 72 percent of the population in high-income countries has received at least one dose of the vaccine, whereas the number stands at 15 percent in low-income countries.

This inequity is worsening vulnerabilities across the world, says Lawrence Young, a virologist and co-lead of the Warwick Health Global Research Priority at the UK-based University of Warwick. “As long as the virus continues to spread and replicate, particularly in populations who are under-vaccinated, it will throw up new variants and these will remain a continual threat even to those countries with high rates of vaccination,” says Young, “Therefore, it is in all our interests to ensure that vaccines are distributed equitably across the world.”

“When your house is on fire, you don't call the patent attorney,” says Hotez. “We wanted to be the fire department.”

The vaccine developed by Hotez and Bottazzi recently received emergency use authorisation in India, which plans to manufacture 100 million doses every month. Dubbed ‘Corbevax’ by its Indian maker, Biological E Limited, the vaccine is now being administered in India to children aged 12-14. The patent-free arrangement means that other low- and middle-income countries could also produce and distribute the vaccine locally.

“When your house is on fire, you don't call the patent attorney, you call the fire department,” says Hotez, commenting on the intellectual property rights waiver. “We wanted to be the fire department.”

The Inequity

Vaccine equity simply means that all people, irrespective of their location, should have equal access to vaccines. However, data suggests that the global COVID-19 vaccine rollout has favoured those in richer countries. For instance, high-income countries like the UAE, Portugal, Chile, Singapore, Australia, Malta, Hong Kong and Canada have partially vaccinated over 85 percent of their populations. This percentage in poorer countries, meanwhile, is abysmally low – 2.1 percent in Yemen, 4.6 in South Sudan, 5 in Cameroon, 9.9 in Burkina Faso, 10 in Nigeria, 12 in Somalia, 12 in Congo, 13 in Afghanistan and 21 in Ethiopia.

In late 2019, scientists Peter Hotez and Maria Elena Bottazzi set out to create a low-cost vaccine that would help inoculate populations in low- and middle-income countries. In February, they were nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Texas Children's Hospital

The COVID-19 vaccination coverage is particularly low in African countries, and according to Shabir Madhi, a vaccinologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and co-director of African Local Initiative for Vaccinology Expertise, vaccine access and inequity remains a challenge in Africa. Madhi adds that a lack of vaccine access has affected the pandemic’s trajectory on the continent, but a majority of its people have now developed immunity through natural infection. “This has come at a high cost of loss of lives,” he says.

COVID-19 vaccines mean a significant financial burden for poorer countries, which spend an average of $41 per capita annually on health, while the average cost of every COVID-19 vaccine dose ranges between $2 and $40 in addition to a distribution cost of $3.70 per person for two doses. In December last year, the World Health Organisation (WHO) set a goal of immunizing 70 percent of the population of all countries by mid-2022. This, however, means that low-income countries would have to increase their health expenditure by an average of 56.6 percent to cover the cost, as opposed to 0.8 per cent in high-income countries.

Reflecting on the factors that have driven global inequity in COVID-19 vaccine distribution, Andrea Taylor, assistant director of programs at the Duke Global Health Innovation Center, says that wealthy nations took the risk of investing heavily in the development and scaling up of COVID-19 vaccines – at a time when there was little evidence to show that vaccines would work. This reserved a place for these nations at the front of the queue when doses started rolling off production lines. Lower-income countries, meanwhile, could not afford such investments.

“Now, however, global supply is not the issue,” says Taylor. “We are making plenty of doses to meet global need. The main problem is infrastructure to get the vaccine where it is most needed in a predictable and timely way and to ensure that countries have all the support they need to store, transport, and use the vaccine once it is received.”

Taufique Joarder, vice-chairperson of Bangladesh's Public Health Foundation, sees the need for more trials and data before Corbevax is made available to the general population.

In addition to global inequities in vaccination coverage, there are inequities within nations. Taufique Joarder, vice-chairperson of Bangladesh’s Public Health Foundation, points to the situation in his country, where vaccination coverage in rural and economically disadvantaged communities has suffered owing to weak vaccine-promotion initiatives and the difficulty many people face in registering online for jabs.

Joarder also cites the example of the COVID-19 immunization drive for children aged 12 years and above. “[Children] are given the Pfizer vaccine, which requires an ultralow temperature for storage. This is almost impossible to administer in many parts of the country, especially the rural areas. So, a large proportion of the children are being left out of vaccination,” says Joarder, adding that Corbevax, which is cheaper and requires regular temperature refrigeration “can be an excellent alternative to Pfizer for vaccinating rural children.”

Corbevax vs. mRNA Vaccines

As opposed to most other COVID-19 vaccines, which use the new Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine technology, Corbevax is an “old school” vaccine, says Hotez. The vaccine is made through microbial fermentation in yeast, similar to the process used to produce the recombinant hepatitis B vaccine, which has been administered to children in several countries for decades. Hence, says Hotez, the technology to produce Corbevax at large scales is already in place in countries like Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, among many others.

“So if you want to rapidly develop and produce and empower low- and middle-income countries, this is the technology to do it,” he says.

“Global access to high-quality vaccines will require serious investment in other types of COVID-19 vaccines," says Andrea Taylor.

The COVID-19 vaccines created by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna marked the first time that mRNA vaccine technology was approved for use. However, scientists like Young feel that there is “a need to be pragmatic and not seduced by new technologies when older, tried and tested approaches can also be effective.” Taylor, meanwhile, says that although mRNA vaccines have dominated the COVID-19 vaccine market in the U.S., “there is no clear grounding for this preference in the data we have so far.” She adds that there is also growing evidence that the immunity from these shots may not hold up as well over time as that of vaccines using different platforms.

“The mRNA vaccines are well suited to wealthy countries with sufficient ultra-cold storage and transportation infrastructure, but these vaccines are divas and do not travel well in the rest of the world,” says Taylor. “Global access to high-quality vaccines will require serious investment in other types of COVID-19 vaccines, such as the protein subunit platform used by Novavax and Corbevax. These require only standard refrigeration, can be manufactured using existing facilities all over the world, and are easy to transport.”

Joarder adds that Corbevax is cheaper due to the developers’ waived intellectual rights. It could also be used as a booster vaccine in Bangladesh, where only five per cent of the population has currently received booster doses. “If this vaccine is proved effective for heterologous boosting, [meaning] it works well and is well tolerated as a booster with other vaccines that are available in Bangladesh, this can be useful,” says Joarder.

According to Hotez, Corbevax can play several important roles - as a standalone adult or paediatric vaccine, and as a booster for other vaccines. Studies are underway to determine Corbevax’s effectiveness in these regards, he says.

Need for More Data

Biological E conducted two clinical trials involving 3000 subjects in India, and found Corbevax to be “safe and immunogenic,” with 90 percent effectiveness in preventing symptomatic infections from the original strain of COVID-19 and over 80 percent effectiveness against the Delta variant. The vaccine is currently in use in India, and according to Hotez, it’s in the pipeline at different stages in Indonesia, Bangladesh and Botswana.

However, Corbevax is yet to receive emergency use approval from the WHO. Experts such as Joarder see the need for more trials and data before it is made available to the general population. He says that while the WHO’s emergency approval is essential for global scale-up of the vaccine, we need data to determine age-stratified efficacy of the vaccine and whether it can be used for heterologous boosting with other vaccines. “According to the most recent data, the 100 percent circulating variant in Bangladesh is Omicron. We need to know how effective is Corbevax against the Omicron variant,” says Joarder.

Shabir Madhi, a vaccinologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and co-director of the African Local Initiative for Vaccinology Expertise, says that a majority of people in Africa have now developed immunity through natural infection. “This has come at a high cost of loss of lives."

Shivan Parusnath

Others, meanwhile, believe that availing vaccines to poorer countries is not enough to resolve the inequity. Young, the Warwick virologist, says that the global vaccination rollout has also suffered from a degree of vaccine hesitancy, echoing similar observations by President Biden and Pfizer’s CEO. The problem can be blamed on poor communication about the benefits of vaccination. “The Corbevax vaccine [helps with the issues of] patent protection, vaccine storage and distribution, but governments need to ensure that their people are clearly informed.” Notably, however, some research has found higher vaccine willingness in lower-income countries than in the U.S.

Young also emphasized the importance of establishing local vaccination stations to improve access. For some countries, meanwhile, it may be too late. Speaking about the African continent, Madhi says that Corbevax has arrived following the peak of the crisis and won’t reverse the suffering and death that has transpired because of vaccine hoarding by high-income countries.

“The same goes for all the sudden donations from countries such as France - pretty much of little to no value when the pandemic is at its tail end,” says Madhi. “This, unfortunately, is a repeat of the swine flu pandemic in 2009, when vaccines only became available to Africa after the pandemic had very much subsided.”

As We Wait for a Vaccine, Scientists Work to Scale Up the Best COVID-19 Antibodies to Give New Patients

In this illustration of immune defense, Y-shaped proteins called antibodies attack a virus.

When we get sick, our immune system sends its soldier cells to the battlefield. Called B-cells, they "examine" the foreign particles that shouldn't be in our bloodstream—and start producing the antibodies, the proteins to neutralize the invaders.

To screen the antibodies, scientists have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

The better these antibodies are at neutralizing the pathogen, the faster we recover.

The antibodies acquired from COVID-19 survivors already showed promise in treating other patients, but because they must be obtained from people, generating a regular supply is not feasible. To close the gap, researchers are trying to identify the B-cells that make the best antibodies—and then farm them in laboratories at scale.

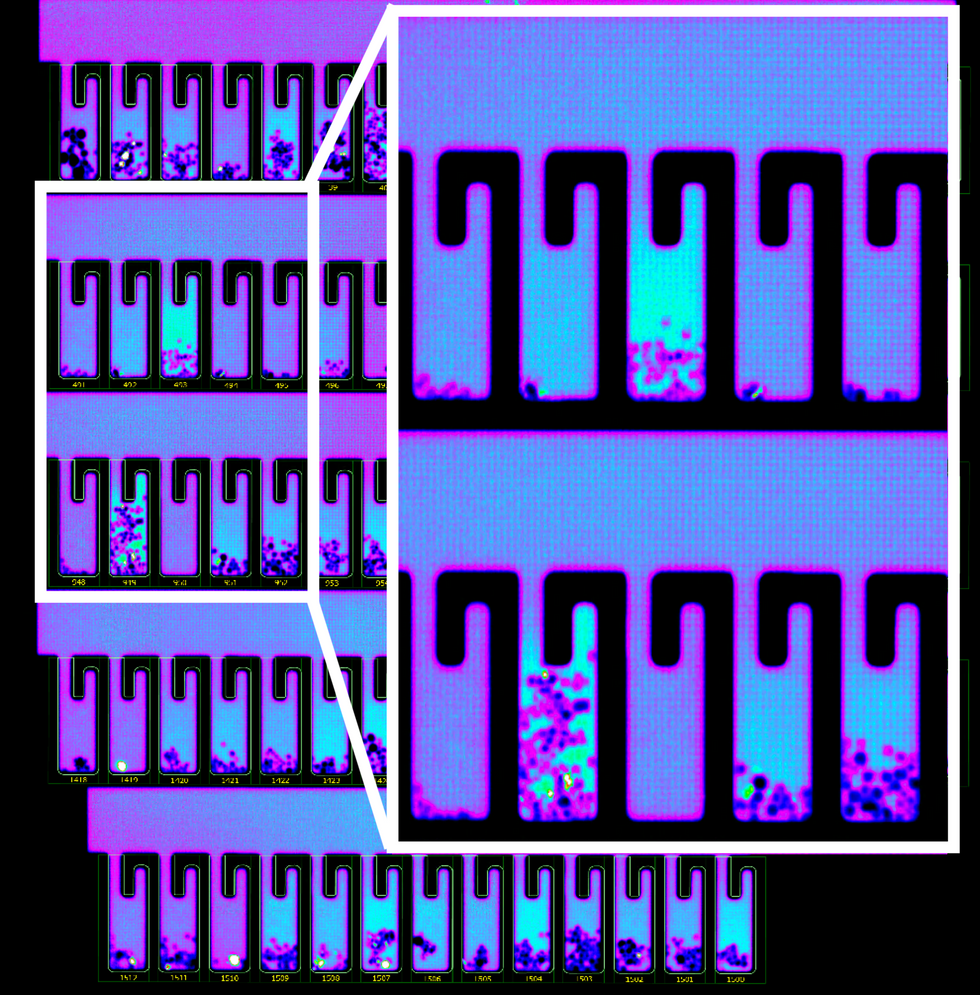

Scientists at Berkley Lights, a biotechnology company in California, have been screening B-cells from recovered patients and testing the antibodies they release for virus-neutralizing abilities. To screen the antibodies, scientists there have developed a proprietary way to make the effective ones glow – like a literal "lightbulb" moment.

So how does it work? First, the individual B-cells are placed into microscopic chambers called nano-pens, where they secrete the antibodies. Once released, the antibodies are flushed over tiny beads that have bits of the viral particles attached to them, along with special molecules that can emit fluorescent light.

"When an antibody binds to the bead, we see a bright light on the bead," explains John Proctor, the company's senior vice president of antibody therapeutics. "So we can identify which cells are making the antibodies."

Then the antibodies are tested for their ability to counteract the coronavirus's spike proteins, which the virus uses to break into our cells. Not all antibodies are equally good at this crucial defense move—some can block only parts of the virus's machinery, while others can neutralize it completely. Proctor and his colleagues are looking for the latter.

Once scientists identify the best performing B-cells, they crack the cells open—or in scientific terms "lyse" them—and extract the genetic instructions for making the antibodies. As it turns out, B-cells aren't very efficient at pumping out massive amounts of antibodies, so scientists insert these genetic instructions into a different, more prolific type of cell.

Named Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells or CHO, these cells are commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry because they can generate therapeutic proteins en masse. Under the right nutrient conditions, which include a lot of sugar, CHO cells can keep making the antibodies at commercial levels. "They are engineered to operate in very large bioreactors," Proctor explains.

While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours.

Berkeley Lights' technology has already been used to screen the antibodies of recovered patients from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In another example, a biotech company GenScript ProBio used the platform to screen mice engineered to have human antibodies for the coronavirus.

In addition to its small, lab-on-a-chip size, Berkeley Lights' system allows scientists to greatly speed up the screening process. While traditional antibody screening can take three months, the Beacon System can do it in less than 24 hours. "We only need one B-cell per pen and a couple of beads to see that fluorescent signal," Proctor says. "It is a more advanced way to process and analyze cells, and that level of sensitivity is unique to our technology."

B-cells secreting antibodies inside the Berkeley Lights Beacon System Nano-Pens.

While vaccines are likely to take months to develop and test, antibodies might arrive to the battleground sooner. With the extremely limited treatment options for COVID-19, antibody-based therapeutics can potentially bridge this gap.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

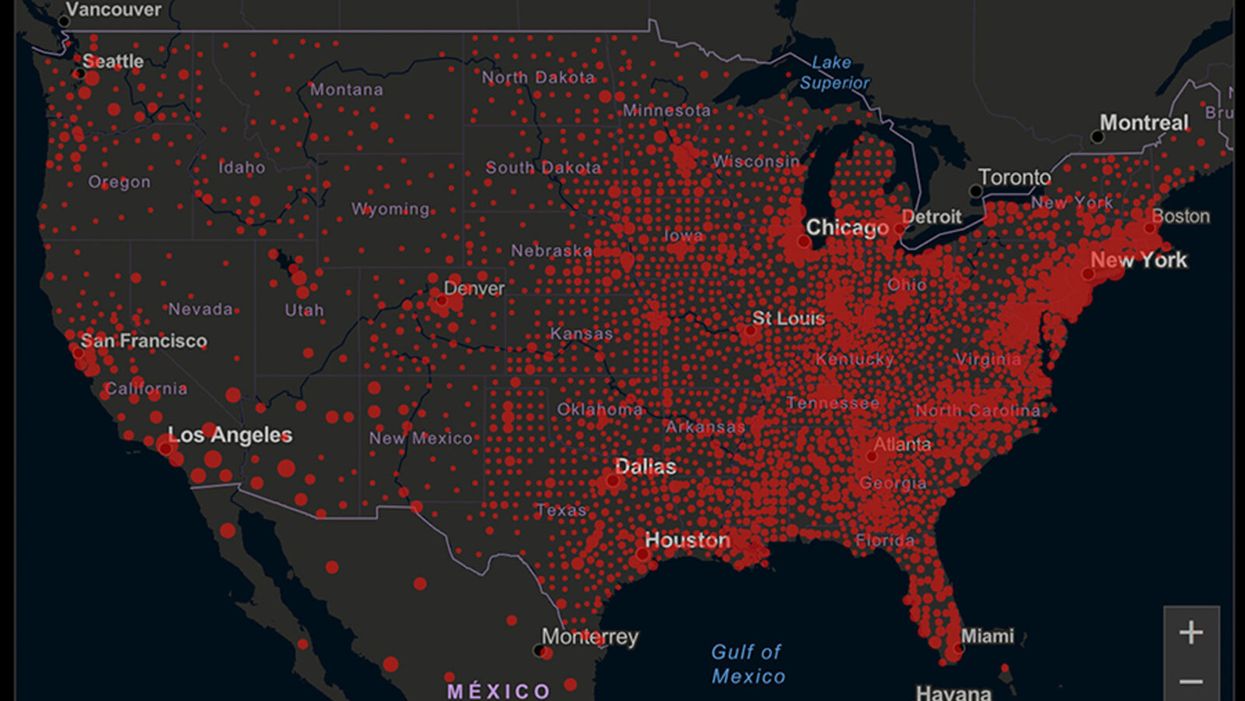

A map of cumulative known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., as of June 12th, 2020.

Have you felt a bit like an armchair epidemiologist lately? Maybe you've been poring over coronavirus statistics on your county health department's website or on the pages of your local newspaper.

If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

You're likely to find numbers and charts but little guidance about how to interpret them, let alone use them to make day-to-day decisions about pandemic safety precautions.

Enter the gurus. We asked several experts to provide guidance for laypeople about how to navigate the numbers. Here's a look at several common COVID-19 statistics along with tips about how to understand them.

Case Counts: Consider the Context

The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in American counties is widely available. Local and state health departments should provide them online, or you can easily look them up at The New York Times' coronavirus database. However, you need to be cautious about interpreting them.

"Case counts are the obvious numbers to look at. But they're probably the hardest thing to sort out," said Dr. Jeff Martin, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Francisco.

That's because case counts by themselves aren't a good window into how the coronavirus is affecting your community since they rely on testing. And testing itself varies widely from day to day and community to community.

"The more testing that's done, the more infections you'll pick up," explained Dr. F. Perry Wilson, a physician at Yale University. The numbers can also be thrown off when tests are limited to certain groups of people.

"If the tests are being mostly given to people with a high probability of having been infected -- for example, they have had symptoms or work in a high-risk setting -- then we expect lots of the tests to be positive. But that doesn't tell us what proportion of the general public is likely to have been infected," said Eleanor Murray, an epidemiologist at Boston University.

These Stats Are More Meaningful

According to Dr. Wilson, it's more useful to keep two other statistics in mind: the number of COVID tests that are being performed in your community and the percentage that turn up positive, showing that people have the disease. (These numbers may or may not be available locally. Check the websites of your community's health department and local news media outlets.)

If the number of people being tested is going up, but the percentage of positive tests is going down, Dr. Wilson said, that's a good sign. But if both numbers are going up – the number of people tested and the percentage of positive results – then "that's a sign that there are more infections burning in the community."

It's especially worrisome if the percentage of positive cases is growing compared to previous days or weeks, he said. According to him, that's a warning of a "high-risk situation."

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at University of California at San Francisco, offered this tip: If the percentage of positive tests steadily stays under 8 percent, that's generally a good sign.

There's one more caveat about case counts. It takes an average of a week for someone to be infected with COVID-19, develop symptoms, and get tested, Dr. Rutherford said. It can take an additional several days for those test results to be reported to the county health department. This means that case numbers don't represent infections happening right now, but instead are a picture of the state of the pandemic more than a week ago.

Hospitalizations: Focus on Current Statistics

You should be able to find numbers about how many people in your community are currently hospitalized – or have been hospitalized – with diagnoses of COVID-19. But experts say these numbers aren't especially revealing unless you're able to see the number of new hospitalizations over time and track whether they're rising or falling. This number often isn't publicly available, however.

If new hospitalizations are increasing, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

And there's an important caveat: "The problem with hospitalizations is that they do lag," UC San Francisco's Dr. Martin said, since it takes time for someone to become ill enough to need to be hospitalized. "They tell you how much virus was being transmitted in your community 2 or 2.5 weeks ago."

Also, he said, people should be cautious about comparing new hospitalization rates between communities unless they're adjusted to account for the number of more-vulnerable older people.

Still, if new hospitalizations are increasing, he said, "you may want to react by being more careful yourself."

Deaths: They're an Even More Delayed Headline

Cable news networks obsessively track the number of coronavirus deaths nationwide, and death counts for every county in the country are available online. Local health departments and media websites may provide charts tracking the growth in deaths over time in your community.

But while death rates offer insight into the disease's horrific toll, they're not useful as an instant snapshot of the pandemic in your community because severely ill patients are typically sick for weeks. Instead, think of them as a delayed headline.

"These numbers don't tell you what's happening today. They tell you how much virus was being transmitted 3-4 weeks ago," Dr. Martin said.

'Reproduction Value': It May Be Revealing

You're not likely to find an available "reproduction value" for your community, but it is available for your state and may be useful.

A reproduction value, also known as R0 or R-naught, "tells us how many people on average we expect will be infected from a single case if we don't take any measures to intervene and if no one has been infected before," said Boston University's Murray.

As The New York Times explained, "R0 is messier than it might look. It is built on hard science, forensic investigation, complex mathematical models — and often a good deal of guesswork. It can vary radically from place to place and day to day, pushed up or down by local conditions and human behavior."

It may be impossible to find the R0 for your community. However, a website created by data specialists is providing updated estimates of a related number -- effective reproduction number, or Rt – for each state. (The R0 refers to how infectious the disease is in general and if precautions aren't taken. The Rt measures its infectiousness at a specific time – the "t" in Rt.) The site is at rt.live.

"The main thing to look at is whether the number is bigger than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently growing in your area, or smaller than 1, meaning the outbreak is currently decreasing in your area," Murray said. "It's also important to remember that this number depends on the prevention measures your community is taking. If the Rt is estimated to be 0.9 in your area and you are currently under lockdown, then to keep it below 1 you may need to remain under lockdown. Relaxing the lockdown could mean that Rt increases above 1 again."

"Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing."

Keep in mind that you can still become infected even if an outbreak in your community appears to be slowing. Low risk doesn't mean no risk.

Putting It All Together: Why the Numbers Matter

So you've reviewed COVID-19 statistics in your community. Now what?

Dr. Wilson suggests using the data to remind yourself that the coronavirus pandemic "is still out there. You need to take it seriously and continue precautions," he said. "Whether they're on the upswing or downswing, no state is safe enough to ignore the precautions about mask wearing and social distancing. 'My state is doing well, no one I know is sick, is it time to have a dinner party?' No."

He also recommends that laypeople avoid tracking COVID-19 statistics every day. "Check in once a week or twice a month to see how things are going," he suggested. "Don't stress too much. Just let it remind you to put that mask on before you get out of your car [and are around others]."