Your Questions Answered About Kids, Teens, and Covid Vaccines

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

On May 13th, scientific and medical experts will discuss and answer questions about the vaccine for those under 16.

This virtual event convened leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about Covid-19 vaccines in kids and teens. Highlight video below.

DATE:

Thursday, May 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

Dr. H. Dele Davies, M.D., MHCM

Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean for Graduate Studies at the University of Nebraska Medical (UNMC). He is an internationally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases and a leader in community health.

Dr. Emily Oster, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics at Brown University. She is a best-selling author and parenting guru who has pioneered a method of assessing school safety.

Dr. Tina Q. Tan, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. She has been involved in several vaccine survey studies that examine the awareness, acceptance, barriers and utilization of recommended preventative vaccines.

Dr. Inci Yildirim, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc.

Associate Professor of Pediatrics (Infectious Disease); Medical Director, Transplant Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine; Associate Professor of Global Health, Yale Institute for Global Health. She is an investigator for the multi-institutional COVID-19 Prevention Network's (CoVPN) Moderna mRNA-1273 clinical trial for children 6 months to 12 years of age.

About the Event Series

This event is the second of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Is It Possible to Predict Your Face, Voice, and Skin Color from Your DNA?

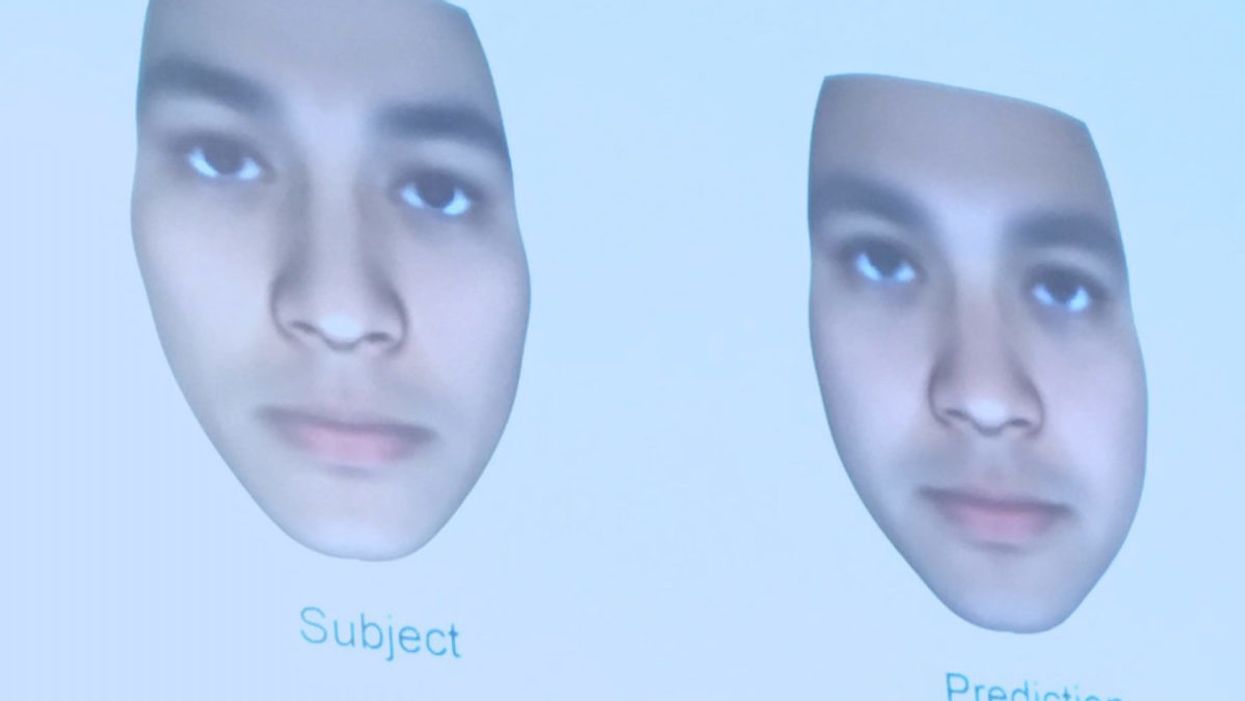

A slide from J. Craig Venter's recent study on facial prediction presented at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

Renowned genetics pioneer Dr. J Craig Venter is no stranger to controversy.

Back in 2000, he famously raced the public Human Genome Project to decode all three billion letters of the human genome for the first time. A decade later, he ignited a new debate when his team created a bacterial cell with a synthesized genome.

Most recently, he's jumped back into the fray with a study in the September issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences about the predictive potential of genomic data to identify individual traits such as voice, facial structure and skin color.

The new study raises significant questions about the privacy of genetic data.

His study applied whole-genome sequencing and statistical modeling to predict traits in 1,061 people of diverse ancestry. His approach aimed to reconstruct a person's physical characteristics based on DNA, and 74 percent of the time, his algorithm could correctly identify the individual in a random lineup of 10 people from his company's database.

While critics have been quick to cast doubt on the plausibility of his claims, the ability to discern people's observable traits, or phenotypes, from their genomes may grow more precise as technology improves, raising significant questions about the privacy and usage of genetic information in the long term.

J. Craig Venter showing slides from his recent study on facial prediction at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

(Courtesy of Kira Peikoff)

Critics: Study Was Incomplete, Problematic

Before even redressing these potential legal and ethical considerations, some scientists simply said the study's main result was invalid. They pointed out that the methodology worked much better in distinguishing between people of different ethnicities than those of the same ethnicity. One of the most outspoken critics, Yaniv Erlich, a geneticist at Columbia University, said, "The method doesn't work. The results were like, 'If you have a lineup of ten people, you can predict eight."

Erlich, who reviewed Venter's paper for Science, where it was rejected, said that he came up with the same results—correctly predicting eight of ten people—by just looking at demographic factors such as age, gender and ethnicity. He added that Venter's recent rebuttal to his criticism was that 'Once we have thousands of phenotypes, it might work better.' But that, Erlich argued, would be "a major breach of privacy. Nobody has thousands of phenotypes for people."

Other critics suggested that the study's results discourage the sharing of genetic data, which is becoming increasingly important for medical research. They go one step further and imply that people's possible hesitation to share their genetic information in public databases may actually play into Venter's hands.

Venter's own company, Human Longevity Inc., aims to build the world's most comprehensive private database on human genotypes and phenotypes. The vastness of this information stands to improve the accuracy of whole genome and microbiome sequencing for individuals—analyses that come at a hefty price tag. Today, Human Longevity Inc. will sequence your genome and perform a battery of other health-related tests at an entry cost of $4900, going up to $25,000. Venter initially agreed to comment for this article, but then could not be reached.

"The bigger issue is how do we understand and use genetic information and avoid harming people."

Opens Up Pandora's Box of Ethical Issues

Whether Venter's study is valid may not be as important as the Pandora's box of potential ethical and legal issues that it raises for future consideration. "I think this story is one along a continuum of stories we've had on the issue of identifiability based on genomic information in the past decade," said Amy McGuire, a biomedical ethics professor at Baylor College of Medicine. "It does raise really interesting and important questions about privacy, and socially, how we respond to these types of scientific advancements. A lot of our focus from a policy and ethics perspective is to protect privacy."

McGuire, who is also the Director of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor, added that while protecting privacy is very important, "the bigger issue is how do we understand and use genetic information and avoid harming people." While we've taken "baby steps," she said, towards enacting laws in the U.S. that fight genetic determinism—such as the Genetic Information and Nondiscrimination Act, which prohibits discrimination based on genetic information in health insurance and employment—some areas remain unprotected, such as for life insurance and disability.

J. Craig Venter showing slides from his recent study on facial prediction at the Summit Conference in Los Angeles on Nov. 3, 2017.

(Courtesy of Kira Peikoff)

Physical reconstructions like those in Venter's study could also be inappropriately used by law enforcement, said Leslie Francis, a law and philosophy professor at the University of Utah, who has written about the ethical and legal issues related to sharing genomic data.

"If [Venter's] findings, or findings like them, hold up, the implications would be significant," Francis said. Law enforcement is increasingly using DNA identification from genetic material left at crime scenes to weed out innocent and guilty suspects, she explained. This adds another potentially complicating layer.

"There is a shift here, from using DNA sequencing techniques to match other DNA samples—as when semen obtained from a rape victim is then matched (or not) with a cheek swab from a suspect—to using DNA sequencing results to predict observable characteristics," Francis said. She added that while the former necessitates having an actual DNA sample for a match, the latter can use DNA to pre-emptively (and perhaps inaccurately) narrow down suspects.

"My worry is that if this [the study's methodology] turns out to be sort-of accurate, people will think it is better than what it is," said Francis. "If law enforcement comes to rely on it, there will be a host of false positives and false negatives. And we'll face new questions, [such as] 'Which is worse? Picking an innocent as guilty, or failing to identify someone who is guilty?'"

Risking Privacy Involves a Tradeoff

When people voluntarily risk their own privacy, that involves a tradeoff, McGuire said. A 2014 study that she conducted among people who were very sick, or whose children were very sick, found that more than half were willing to share their health information, despite concerns about privacy, because they saw a big benefit in advancing research on their conditions.

"We've focused a lot of our policy attention on restricting access, but we don't have a system of accountability when there's a breach."

"To make leaps and bounds in medicine and genomics, we need to create a database of millions of people signing on to share their genetic and health information in order to improve research and clinical care," McGuire said. "They are going to risk their privacy, and we have a social obligation to protect them."

That also means "punishing bad actors," she continued. "We've focused a lot of our policy attention on restricting access, but we don't have a system of accountability when there's a breach."

Even though most people using genetic information have good intentions, the consequences if not are troubling. "All you need is one bad actor who decimates the trust in the system, and it has catastrophic consequences," she warned. That hasn't happened on a massive scale yet, and even if it did, some experts argue that obtaining the data is not the real risk; what is more concerning is hacking individuals' genetic information to be used against them, such as to prove someone is unfit for a particular job because of a genetic condition like Alzheimer's, or that a parent is unfit for custody because of a genetic disposition to mental illness.

Venter, in fact, told an audience at the recent Summit conference in Los Angeles that his new study's approach could not only predict someone's physical appearance from their DNA, but also some of their psychological traits, such as the propensity for an addictive personality. In the future, he said, it will be possible to predict even more about mental health from the genome.

What is most at risk on a massive scale, however, is not so much genetic information as demographic identifiers included in medical records, such as birth dates and social security numbers, said Francis, the law and philosophy professor. "The much more interesting and lucrative security breaches typically involve not people interested in genetic information per se, but people interested in the information in health records that you can't change."

Hospitals have been hacked for this kind of information, including an incident at the Veterans Administration in 2006, in which the laptop and external hard drive of an agency employee that contained unencrypted information on 26.5 million patients were stolen from the employee's house.

So, what can people do to protect themselves? "Don't share anything you wouldn't want the world to see," Francis said. "And don't click 'I agree' without actually reading privacy policies or terms and conditions. They may surprise you."

"There's a Bacteria For That"

Bacteria Lactobacillus, gram-positive rod-shaped lactic acid bacteria which are part of normal flora of human intestine are used as probiotics and in yogurt production, close-up view. (Image copyright: Fotolia)

"There's an app for that." Get ready for a cutting-edge twist on this common phrase. In the life sciences, researchers in the field of synthetic biology are engineering microbes to execute specific tasks, like diagnosing gut inflammation, purifying dirty water, and cleaning up oil spills. Here are five academic and commercial projects underway now that will make you want to add the term "designer bacteria" to your vocab.

1) Bacteria that can sense, diagnose and treat disorders of the gut.

Dr. Pamela Silver at Harvard Medical School has engineered non-pathenogenic strains of E. Coli bacteria, which she calls "living diagnostics and therapeutics," to accurately sense whether an animal has been exposed to antibiotics and whether inflammation is present in its intestines.

Imagine a "living FitBit" that could report on your gut health in real time.

So how does it work? "The bacteria have a genetic switch like a light switch," she explains, "and when they are exposed to an antibiotic or an inflammatory response, the light switch flips to on and the bacteria turn color." In a study that Silver and her colleagues published earlier this year, the bacteria in mouse guts turned blue when exposed to the chemical tetrathionate, which is produced during inflammation. Then, when the animal excreted waste, its feces were also blue. For safety reasons, the excreted bacteria can additionally be programmed to self-destruct so as not to contaminate the environment.

The implications for human health go way beyond a non-invasive alternative to colonoscopies. Imagine "a living FitBit," Silver says with a laugh – a probiotic your doctor could prescribe that could colonize your gut to report on your intestinal health and your diet—and even treat pathogens at the same time. Another potential application is to deploy this new tool in the skin as a living sensor. "Your skin has a defined population of bacteria and those could be engineered to sense a lot," she says, such as pathological changes and toxic environmental exposures.

But one big social question in this emerging research remains how open the public and regulators will be to genetically modified organisms as drugs. Silver says that acceptance will require "patient advocacy, education, and showing these actually work. We have shown in an animal that it can work. So far, in humans, it's unclear."

"Live biotherapeutic products" is a whole new category of drug.

2) Bacteria that can treat a rare metabolic disease.

The startup company Synlogic, based in Cambridge, Mass., has designed an experimental pill containing a strain of E. Coli bacteria that can soak up excess ammonia in a person's stomach, treating those who suffer from toxic elevated blood ammonia levels. This condition, called hyperammonemia, can occur in those with chronic liver disease or genetic urea cycle disorders. The pill is genetically engineered to convert ammonia into a beneficial amino acid instead.

Just a few weeks ago, the company announced positive data from its Phase 1 trial, in which the pill was tested on a group of 52 healthy volunteers for the first time. The study was randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled, which means that neither the researchers nor the subjects knew who was getting the active pill vs. a sham one. This design is the gold standard in clinical research because it overcomes bias and produces objective results. So far, the pill appears to be safe and well-tolerated, and the company plans to continue the next phase of testing in 2018. Synlogic's treatment stands to be the first of this category of therapy—called "live biotherapeutic products"—that will be scrutinized by the FDA when the time comes for possible market approval.

3) Bacteria that can be sprayed on land to clean up an oil spill.

"This is science fiction, but it's become a lot less science fiction in the last couple of years," says Floyd E. Romesberg, a professor of chemistry whose lab at the Scripps Research Institute in California is on the forefront of synthetic biology.

"We have literally increased the biology that cells can write stories with."

His lab has added two new letters to the code of life. At the most fundamental level, all life on Earth, including human, animal, and bacteria, relies on the four "letters" or chemical building blocks of A, T, C, and G to store biological information inside a cell and then retrieve it in the form of proteins that perform essential tasks. For the first time in history, Romesberg and his team have now developed an unnatural base pair—an X and a Y—capable of storing increased information.

"We have literally increased the biology that cells can write stories with," he says. "With new letters, you can write new words, new sentences, and you can tell new stories, as opposed to taking the limited vocabulary you have and trying to rearrange it."

The implications of his research are immense; applications range from developing therapeutic proteins as drugs, to bestowing cells with new properties, such as oxidizing oil after a spill. He imagines a future scenario in which, for example, specially engineered bacteria are sprayed on a beach, eat the oil for three generations of their life—less than a day—and then die off, since they will be unable to replicate their own DNA. Afterwards, the beach is clean.

"What we are struggling with now is the first steps toward doing that – the cell relying on unnatural information to survive, rather than doing something new yet," he says, "but that's where we are headed."

4) Bacteria that can deliver cancer-killing drugs inside tumors.

Researcher Jeff Hasty at UCSD has engineered a strain of Salmonella bacteria to penetrate cancer tumors and deliver drugs that stop their growth. His approach is especially clever because it solves a major problem in cancer drug delivery: chemotherapy relies on blood vessels for transit, but blood vessels don't exist deep inside tumors. Using this fact to his advantage, Hasty and his team designed bacteria that can sneak drugs all the way into a tumor and then self-destruct, taking the tumor down in the process.

So far, the treatment in mice has been successful; their tumors stopped growing after they were given the bacteria, and along with the use of chemotherapy, their life expectancy increased by half.

Many questions remain in terms of applicability to tumors in human beings, but the notion of a bacterial therapy remains a promising clinical approach for treating cancer in the future.

Craft beer experts couldn't tell the difference between beer brewed with regular vs. recycled water.

5) Bacteria that can convert wastewater into drinkable water.

Boston-based company Cambrian Innovation has a patented product called the EcoVolt MINI that uses microbes to generate energy through contact with electrodes. The company has collaborated with breweries across the country, taking their waste water and converting it to clean water and clean energy. Through the company's bioelectrochemical system, microbes eat the contaminants in the wastewater, and as a byproduct they produce methane, which can be converted to heat and power; in some cases, the process generates enough energy to send some back to the brewery.

"The main goal of the system is to produce cleaner water; the energy is an added product," explains Claire Aviles, Cambrian's marketing and communications manager.

The wastewater treatment is so effective that the water can be made suitable for reuse. One brewery client, for example, recently experimented with using the recycled water to brew a beer at a festival in California. They used the same recipe for two beers—one with typical city water and one with recycled water from Cambrian's system—and offered a side-by-side taste test to consumers and craft beer experts alike.

"Most people couldn't tell which was which," Aviles says.

In fact, most of the tasters preferred the beer brewed with the recycled water.

Turns out bacteria aren't always dirty after all.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.