A Stomach Implant Saved Me. When Your Organs Fail, You Could Become a Cyborg, Too

Ordinary people are living better with chronic conditions thanks to a recent explosion of developments in medical implants.

Beware, cyborgs walk among us. They’re mostly indistinguishable from regular humans and are infiltrating every nook and cranny of society. For full disclosure, I’m one myself. No, we’re not deadly intergalactic conquerors like the Borg race of Star Trek fame, just ordinary people living better with chronic conditions thanks to medical implants.

In recent years there has been an explosion of developments in implantable devices that merge multiple technologies into gadgets that work in concert with human physiology for the treatment of serious diseases. Pacemakers for the heart are the best-known implants, as well as other cardiac devices like LVADs (left-ventricular assist devices) and implanted defibrillators. Next-generation devices address an array of organ failures, and many are intended as permanent. The driving need behind this technology: a critical, persistent shortage of implantable biological organs.

The demand for transplantable organs dwarfs their availability. There are currently over 100,000 people on the transplant waiting list in the U.S., compared to 40,000 transplants completed in 2021. But even this doesn’t reflect the number of people in dire straits who don’t qualify for a transplant because of things like frailty, smoking status and their low odds of surviving the surgery.

My journey to becoming a cyborg came about because of a lifelong medical condition characterized by pathologically low motility of the digestive system, called gastroparesis. Ever since I was in my teens, I’ve had chronic problems with severe nausea. Flareups can be totally incapacitating and last anywhere from hours to months, interspersed with periods of relief. The cycle is totally unpredictable, and for decades my condition went both un- and misdiagnosed by doctors who were not even aware that the condition existed. Over the years I was labeled with whatever fashionable but totally inappropriate medical label existed at the time, and not infrequently, hypochondria.

Living with the gastric pacer is easy. In fact, most of the time, I don’t even know it’s there.

One of the biggest turning points in my life came when a surgeon at the George Washington University Hospital, Dr. Frederick Brody, ordered a gastric emptying test that revealed gastroparesis. This was in 2009, and an implantable device, called a gastric pacer, had been approved by the FDA for compassionate use, meaning that no other treatments were available. The small device is like a pacemaker that’s implanted beneath the skin of the abdomen and is attached to the stomach through electrodes that carry electrical pulses that stimulate the stomach, making it contract as it’s supposed to.

Dr. Brody implanted the electrical wires and the device, and, once my stomach started to respond to the pulses, I got the most significant nausea relief I’d had in decades of futile treatments. It sounds cliché to say that my debt to Dr. Brody is immeasurable, but the pacer has given me more years of relative normalcy than I previously could have dreamed of.

I should emphasize that the pacer is not a cure. I still take a lot of medicine and have to maintain a soft, primarily vegetarian diet, and the condition has progressed with age. I have ups and downs, and can still have periods of severe illness, but there’s no doubt I would be far worse off without the electrical stimulation provided by the pacer.

Living with the gastric pacer is easy. In fact, most of the time, I don’t even know it’s there. It entails periodic visits with a surgeon who can adjust the strength of the electrical pulses using a wireless device, so when symptoms are worse, he or she can amp up the juice. If the pulses are too strong, they can cause annoying contractions in the abdominal muscles, but this is easily fixed with a simple wireless adjustment. The battery runs down after a few years, and when this happens the whole device has to be replaced in what is considered minor surgery.

Such devices could fill gaps in treating other organ failures. By far most of the people on transplant waiting lists are waiting for kidneys. Despite the fact that live donations are possible, there’s still a dire shortage of organs. A bright spot on the horizon is The Kidney Project, a program spearheaded by bioengineer Shuvo Roy at the University of California, San Francisco, which is developing a fully implantable artificial kidney. The device combines living cells with artificial materials and relies not on a battery, but on the patient’s own blood pressure to keep it functioning.

Several years into this project, a prototype of the kidney, about the size of a smart phone, has been successfully tested in pigs. The device seems to provide many of the functions of a biological kidney (unlike dialysis, which replaces only one main function) and reliably produces urine. One of its most critical components is a special artificial membrane, called a hemofilter, that filters out toxins and waste products from the blood without leaking important molecules like albumin. Since it allows for total mobility, the artificial kidney will provide patients with a higher quality of life than those on dialysis, and is in some important ways, even better than a biological transplant.

The beauty of the device is that, even though it contains kidney cells sourced, as of now, from cadavers or pigs, the cells are treated so that they can’t be rejected and the device doesn’t require the highly problematic immunosuppressant drugs a biological organ requires. “Anti-rejection drugs,” says Roy, “make you susceptible to all kinds of infections and damage the transplanted organ, causing steady deterioration. Eventually they kill the kidney. A biological transplant has about a 10-year limit,” after which the kidney fails and the body rejects it.

Eventually, says Roy, the cells used in the artificial kidney will be sourced from the patient himself, the ultimate genetic match. The patient’s adult stem cells can be used to produce some or all of the 25 to 30 specialized cells of a biological kidney that provide all the functions of a natural organ. People formerly on dialysis could drastically improve their functionality and quality of life without being tethered to a machine for hours at a time, three days a week.

As exciting as this project is, it suffers from a common theme in early biomedical research—keeping a steady stream of funding that will move the project from the lab, into human clinical trials and eventually to the bedside. “It’s the issue,” says Roy. “Potential investors want to see more data indicating that it works, but you need funding to create data. It’s a Catch-22 that puts you in a kind of no-man’s land of funding.” The constant pursuit of funding introduces a variable that makes it hard to predict when the kidney will make it to market, despite the enormous need for such a technology.

Another critical variable is if and when insurance companies will decide to cover transplants with the artificial kidney, so that it becomes affordable for the average person. But Roy thinks that this hurdle, too, will be crossed. Insurance companies stand to save a great deal of money compared to what they ordinarily spend on transplant patients. The cost of yearly maintenance will be a fraction of that associated with the tens of thousands of dollars for immunosuppressant drugs and the attendant complications associated with a biological transplant.

One estimate that the multidisciplinary team of researchers involved with The Kidney Project are still trying to establish is how long the artificial kidney will last once transplanted into the body. Animal trials so far have been looking at how the kidney works for 30 days, and will soon extend that study to 90 days. Additional studies will extend much farther into the future, but first the kidneys have to be implanted into people who can be followed over many years to answer this question. But unlike the gastric pacer and other implants, there won’t be a need for periodic surgeries to replace a depleted battery, and the stark improvements in quality of life compared to dialysis add a special dimension to the value of whatever time the kidney lasts.

Another life-saving implant could address a major scourge of the modern world—heart disease. Despite significant advances in recent decades, including the cardiac implants mentioned above, cardiovascular disease still causes one in three deaths across the world. One of the most promising developments in recent years is the Total Artificial Heart, a pneumatically driven device that can be used in patients with biventricular heart failure, affecting both sides of the heart, when a biological organ is not available.

The TAH is implanted in the chest cavity and has two tubes that snake down the body, come out through the abdomen and attach to a 13.5-pound external driver that the patient carries around in a backpack. It was first developed as a bridge to transplant, a temporary alternative while the patient waited for a biological heart to replace it. However, SynCardia Systems, LLC, the Tucson-based company that makes it, is now investigating whether the heart can be used on a long-term basis.

There’s good reason to think that this will be the case. I spoke with Daniel Teo, one of the board members of SynCardia, who said that so far, one patient lived with the TAH for six years and nine months, before he died of other causes. Another patient, still alive, has lived with the device for over five years and another one has lived with it for over four years. About 2,000 of these transplants have been done in patients waiting for biological hearts so far, and most have lived mobile, even active lives. One TAH recipient hiked for 600 miles, and another ran the 4.2-mile Pat Tillman Run, both while on the artificial heart. This is a far cry from their activities before surgery, while living with advanced heart failure.

Randy Shepard, a recipient of the Total Artificial Heart, teaches archery to his son.

Randy Shepard

If removing and replacing one’s biological heart with a synthetic device sounds scary, it is. But then so is replacing one’s heart with biological one. “The TAH is very emotionally loaded for most people,” says Teo. “People sometimes hold back because of philosophical, existential questions and other nonmedical reasons.” He also cites cultural reasons why some people could be hesitant to accept an artificial heart, saying that some religions could frown upon it, just as they forbid other medical interventions.

The first TAHs that were approved were 70 cubic centimeters in size and fit into the chest cavities of men and larger women, but there’s now a smaller, 50 cc size meant for women and adolescents. The FDA first cleared the 70 cc heart as a bridge to transplant in 2004, and the 50 cc model received approval in 2014. SynCardia’s focus now is on seeking FDA approval to use the heart on a long-term basis. There are other improvements in the works.

One issue being refined deals with the external driver that holds the pneumatic device for moving the blood through a patient’s body. The two tubes connecting the driver to the heart entail openings in the skin that could get infected, and carrying the backpack is less than ideal. The driver also makes an audible sound that some people find disturbing. The next generation TAH will be quieter and involve wearing a smaller, lighter device on a belt rather than carrying the backpack. SynCardia is also working toward a fully implantable heart that wouldn’t require any external components and would contain an energy source that can be recharged wirelessly.

Teo says the jury is out as to whether artificial hearts will ever obviate the need for biological organs, but the world’s number one killer isn’t going away any time soon. “The heart is one of the strongest organs,” he says, “but it’s not made to last forever. If you live long enough, the heart will eventually fail, and heart failure leads to the failure of other organs like the kidney, the lungs and the liver.” As long as this remains the case and as long as the current direction of research continues, artificial organs are likely to play an ever larger part of our everyday lives.

Oh, wait. Maybe we cyborgs will take over the world after all.

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

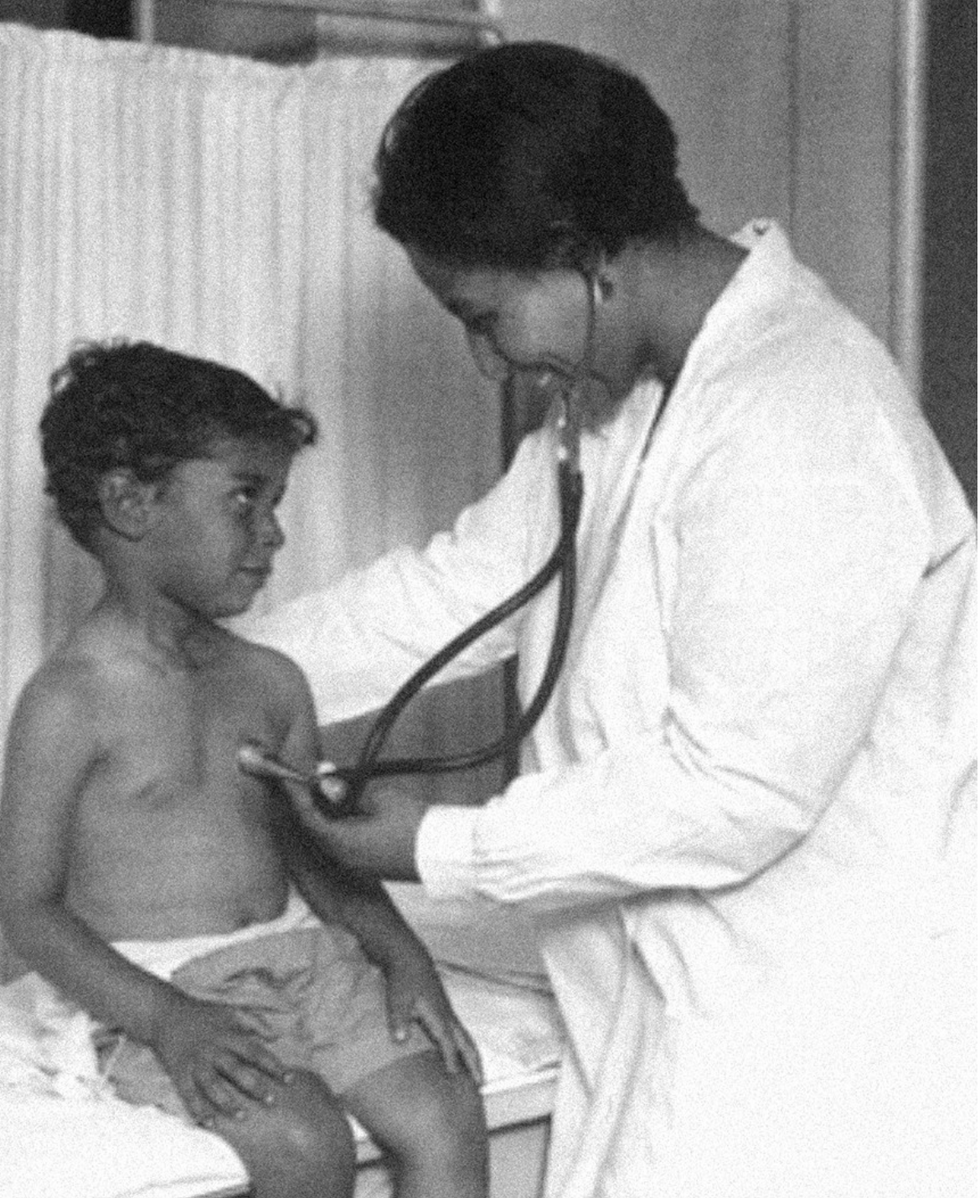

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

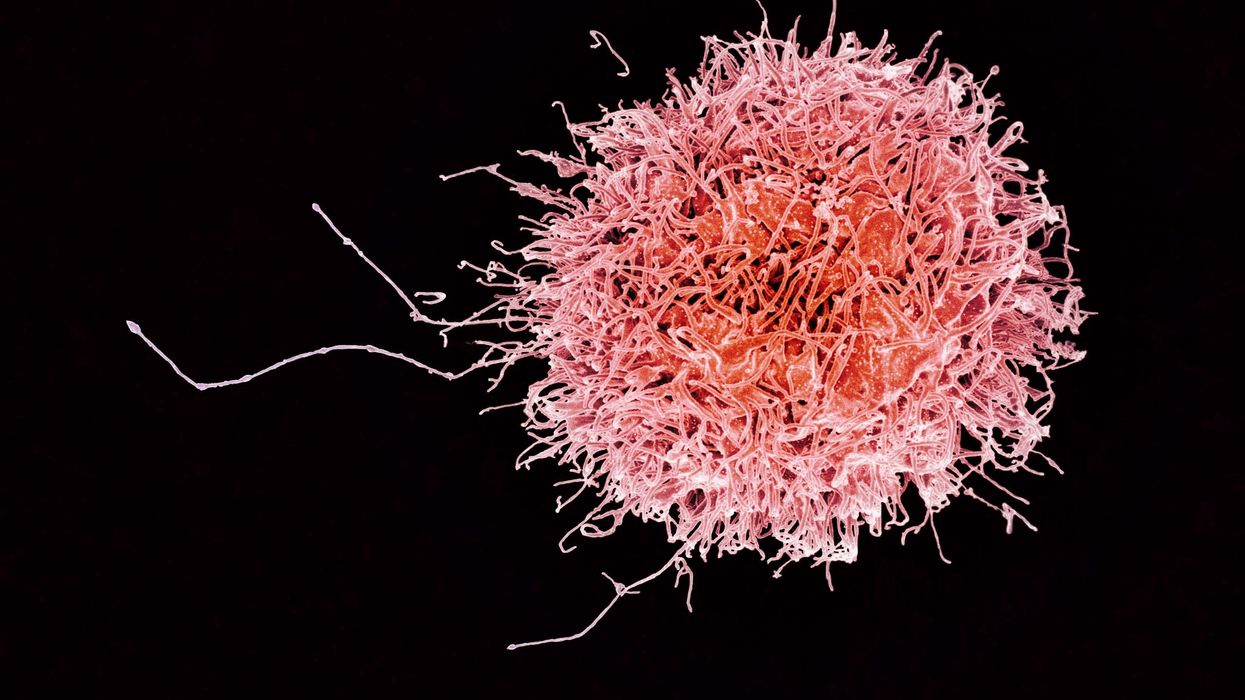

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business