Dadbot, Wifebot, Friendbot: The Future of Memorializing Avatars

In 2015, about a year before he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, John Vlahos posed for a picture with his son, James.

In 2016, when my family found out that my father was dying from cancer, I did something that at the time felt completely obvious: I started building a chatbot replica of him.

I simply wanted to create an interactive way to share key parts of his life story.

I was not under any delusion that the Dadbot, as I soon began calling it, would be a true avatar of him. From my research about the voice computing revolution—Siri, Alexa, the Google Assistant—I knew that fully humanlike AIs, like you see in the movies, were a vast ways from technological reality. Replicating my dad in any real sense was never the goal, anyway; that notion gave me the creeps.

Instead, I simply wanted to create an interactive way to share key parts of his life story: facts about his ancestors in Greece. Memories from growing up. Stories about his hobbies, family life, and career. And I wanted the Dadbot, which sent text messages and audio clips over Facebook Messenger, to remind me of his personality—warm, erudite, and funny. So I programmed it to use his distinctive phrasings; to tell a few of his signature jokes and sing his favorite songs.

While creating the Dadbot, a laborious undertaking that sprawled into 2017, I fixated on two things. The first was getting the programming right, which I did using a conversational agent authoring platform called PullString. The second, far more wrenching concern was my father's health. Failing to improve after chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and steadily losing energy, weight, and the animating sparkle of life, he died on February 9.

John Vlahos at a family reunion in the summer of 2016, a few months after his cancer diagnosis.

(Courtesy James Vlahos)

After a magazine article that I wrote about the Dadbot came out in the summer of 2017, messages poured in from readers. While most people simply expressed sympathy, some conveyed a more urgent message: They wanted their own memorializing chatbots. One man implored me to make a bot for him; he had been diagnosed with cancer and wanted his six-month-old daughter to have a way to remember him. A technology entrepreneur needed advice on replicating what I did for her father, who had stage IV cancer. And a teacher in India asked me to engineer a conversational replica of her son, who had recently been struck and killed by a bus.

Journalists from around the world also got in touch for interviews, and they inevitably came around to the same question. Will virtual immortality, they asked, ever become a business?

The prospect of this happening had never crossed my mind. I was consumed by my father's struggle and my own grief. But the notion has since become head-slappingly obvious. I am not the only person to confront the loss of a loved one; the experience is universal. And I am not alone in craving a way to keep memories alive. Of course people like the ones who wrote me will get Dadbots, Mombots, and Childbots of their own. If a moonlighting writer like me can create a minimum viable product, then a company employing actual computer scientists could do much more.

But this prospect raises unanswered and unsettling questions. For businesses, profit, and not some deeply personal mission, will be the motivation. This shift will raise issues that I didn't have to confront. To make money, a virtual immortality company could follow the lucrative but controversial business model that has worked so well for Google and Facebook. To wit, a company could provide the memorializing chatbot for free and then find ways to monetize the attention and data of whoever communicated with it. Given the copious amount of personal information flowing back and forth in conversations with replica bots, this would be a data gold mine for the company—and a massive privacy risk for users.

Virtual immortality as commercial product will doubtless become more sophisticated.

Alternately, a company could charge for memorializing avatars, perhaps with an annual subscription fee. This would put the business in a powerful position. Imagine the fee getting hiked each year. A customer like me would find himself facing a terrible decision—grit my teeth and keep paying, or be forced to pull the plug on the best, closest reminder of a loved one that I have. The same person would effectively wind up dying twice.

Another way that a beloved digital avatar could die is if the company that creates it ceases to exist. This is no mere academic concern for me: Earlier this year, PullString was swallowed up by Apple. I'm still able to access the Dadbot on my own computer, fortunately, but the acquisition means that other friends and family members can no longer chat with him remotely.

Startups like PullString, of course, are characterized by impermanence; they tend to get snapped up by bigger companies or run out of venture capital and fold. But even if big players like, say, Facebook or Google get into the virtual immortality game, we can't count on them existing even a few decades from now, which means that the avatars enabled by their technology would die, too.

The permanence problem is the biggest hurdle faced by the fledgling enterprise of virtual immortality. So some entrepreneurs are attempting to enable avatars whose existence isn't reliant upon any one company or set of computer servers. "By leveraging the power of blockchain and decentralized software to replicate information, we help users create avatars that live on forever," says Alex Roy, the founder and CEO of the startup Everlife.ai. But until this type of solution exists, give props to conventional technology for preserving memories: printed photos and words on paper can last for centuries.

The fidelity of avatars—just how lifelike they are—also raises serious concerns. Before I started creating the Dadbot, I worried that the tech might be just good enough to remind my family of the man it emulated, but so far off from my real father that it gave us all the creeps. But because the Dadbot was a simple chatbot and not some all-knowing AI, and because the interface was a messaging app, there was no danger of him encroaching on the reality of my actual dad.

But virtual immortality as commercial product will doubtless become more sophisticated. Avatars will have brains built by teams of computer scientists employing the latest techniques in conversational AI. The replicas will not just text but also speak, using synthetic voices that emulate the ones of the people being memorialized. They may even come to life as animated clones on computer screens or in 3D with the help of virtual reality headsets.

What fascinates me is how technology can help to preserve the past—genuine facts and memories from peoples' lives.

These are all lines that I don't personally want to cross; replicating my dad was never the goal. I also never aspired to have some synthetic version of him that continued to exist in the present, capable of acquiring knowledge about the world or my life and of reacting to it in real time.

Instead, what fascinates me is how technology can help to preserve the past—genuine facts and memories from people's lives—and their actual voices so that their stories can be shared interactively after they have gone. I'm working on ideas for doing this via voice computing platforms like Alexa and Assistant, and while I don't have all of the answers yet, I'm excited to figure out what might be possible.

[Adapted from Talk to Me: How Voice Computing Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Think (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 26, 2019).]

The Friday Five: How to exercise for cancer prevention

How to exercise for cancer prevention. Plus, a device that brings relief to back pain, ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk, the world's oldest disease could make you young again, and more.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- How to exercise for cancer prevention

- A device that brings relief to back pain

- Ingredients for reducing Alzheimer's risk

- Is the world's oldest disease the fountain of youth?

- Scared of crossing bridges? Your phone can help

New approach to brain health is sparking memories

This fall, Robert Reinhart of Boston University published a study finding that electrical stimulation can boost memory - and Reinhart was surprised to discover the effects lasted a full month.

What if a few painless electrical zaps to your brain could help you recall names, perform better on Wordle or even ward off dementia?

This is where neuroscientists are going in efforts to stave off age-related memory loss as well as Alzheimer’s disease. Medications have shown limited effectiveness in reversing or managing loss of brain function so far. But new studies suggest that firing up an aging neural network with electrical or magnetic current might keep brains spry as we age.

Welcome to non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). No surgery or anesthesia is required. One day, a jolt in the morning with your own battery-operated kit could replace your wake-up coffee.

Scientists believe brain circuits tend to uncouple as we age. Since brain neurons communicate by exchanging electrical impulses with each other, the breakdown of these links and associations could be what causes the “senior moment”—when you can’t remember the name of the movie you just watched.

In 2019, Boston University researchers led by Robert Reinhart, director of the Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory, showed that memory loss in healthy older adults is likely caused by these disconnected brain networks. When Reinhart and his team stimulated two key areas of the brain with mild electrical current, they were able to bring the brains of older adult subjects back into sync — enough so that their ability to remember small differences between two images matched that of much younger subjects for at least 50 minutes after the testing stopped.

Reinhart wowed the neuroscience community once again this fall. His newer study in Nature Neuroscience presented 150 healthy participants, ages 65 to 88, who were able to recall more words on a given list after 20 minutes of low-intensity electrical stimulation sessions over four consecutive days. This amounted to a 50 to 65 percent boost in their recall.

Even Reinhart was surprised to discover the enhanced performance of his subjects lasted a full month when they were tested again later. Those who benefited most were the participants who were the most forgetful at the start.

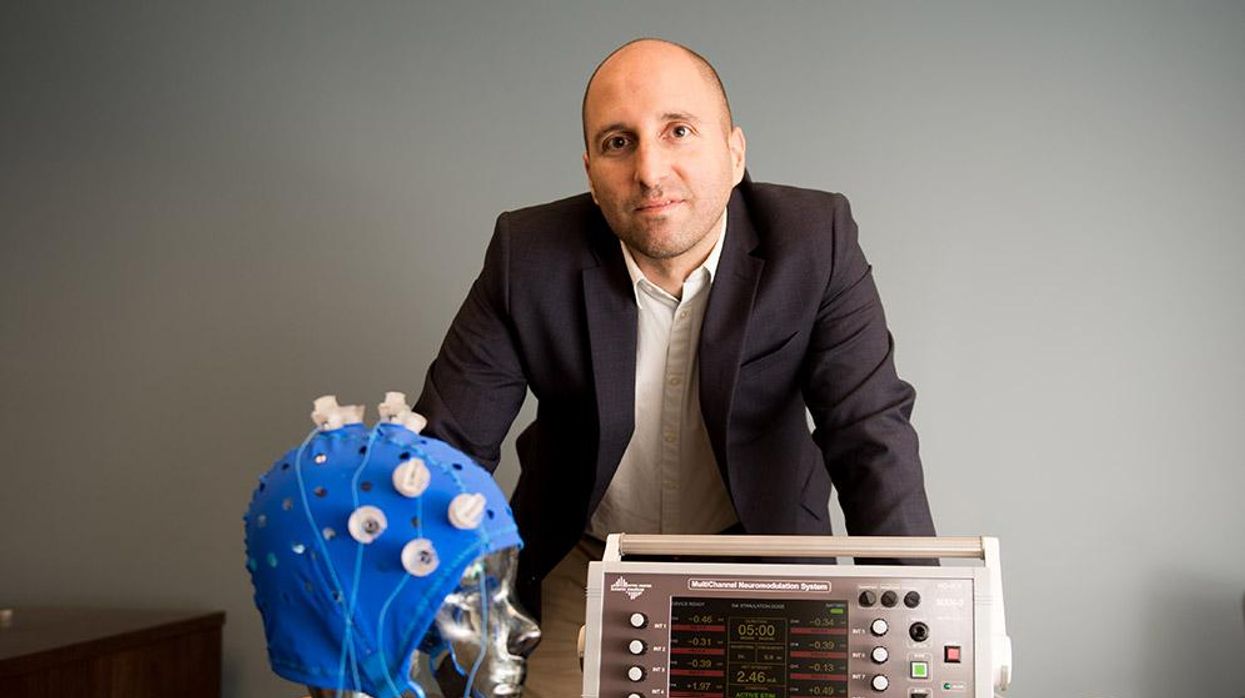

An older person participates in Robert Reinhart's research on brain stimulation.

Robert Reinhart

Reinhart’s subjects only suffered normal age-related memory deficits, but NIBS has great potential to help people with cognitive impairment and dementia, too, says Krista Lanctôt, the Bernick Chair of Geriatric Psychopharmacology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto. Plus, “it is remarkably safe,” she says.

Lanctôt was the senior author on a meta-analysis of brain stimulation studies published last year on people with mild cognitive impairment or later stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The review concluded that magnetic stimulation to the brain significantly improved the research participants’ neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy and depression. The stimulation also enhanced global cognition, which includes memory, attention, executive function and more.

This is the frontier of neuroscience.

The two main forms of NIBS – and many questions surrounding them

There are two types of NIBS. They differ based on whether electrical or magnetic stimulation is used to create the electric field, the type of device that delivers the electrical current and the strength of the current.

Transcranial Current Brain Stimulation (tES) is an umbrella term for a group of techniques using low-wattage electrical currents to manipulate activity in the brain. The current is delivered to the scalp or forehead via electrodes attached to a nylon elastic cap or rubber headband.

Variations include how the current is delivered—in an alternating pattern or in a constant, direct mode, for instance. Tweaking frequency, potency or target brain area can produce different effects as well. Reinhart’s 2022 study demonstrated that low or high frequencies and alternating currents were uniquely tied to either short-term or long-term memory improvements.

Sessions may be 20 minutes per day over the course of several days or two weeks. “[The subject] may feel a tingling, warming, poking or itching sensation,” says Reinhart, which typically goes away within a minute.

The other main approach to NIBS is Transcranial Magnetic Simulation (TMS). It involves the use of an electromagnetic coil that is held or placed against the forehead or scalp to activate nerve cells in the brain through short pulses. The stimulation is stronger than tES but similar to a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

The subject may feel a slight knocking or tapping on the head during a 20-to-60-minute session. Scalp discomfort and headaches are reported by some; in very rare cases, a seizure can occur.

No head-to-head trials have been conducted yet to evaluate the differences and effectiveness between electrical and magnetic current stimulation, notes Lanctôt, who is also a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto. Although TMS was approved by the FDA in 2008 to treat major depression, both techniques are considered experimental for the purpose of cognitive enhancement.

“One attractive feature of tES is that it’s inexpensive—one-fifth the price of magnetic stimulation,” Reinhart notes.

Don’t confuse either of these procedures with the horrors of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the 1950s and ‘60s. ECT is a more powerful, riskier procedure used only as a last resort in treating severe mental illness today.

Clinical studies on NIBS remain scarce. Standardized parameters and measures for testing have not been developed. The high heterogeneity among the many existing small NIBS studies makes it difficult to draw general conclusions. Few of the studies have been replicated and inconsistencies abound.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Lanctôt’s meta-analysis showed improvements in global cognition from delivering the magnetic form of the stimulation to people with Alzheimer’s, and this finding was replicated inan analysis in the Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease this fall. Neither meta-analysis found clear evidence that applying the electrical currents, was helpful for Alzheimer’s subjects, but Lanctôt suggests this might be merely because the sample size for tES was smaller compared to the groups that received TMS.

At the same time, London neuroscientist Marco Sandrini, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Roehampton, critically reviewed a series of studies on the effects of tES on episodic memory. Often declining with age, episodic memory relates to recalling a person’s own experiences from the past. Sandrini’s review concluded that delivering tES to the prefrontal or temporoparietal cortices of the brain might enhance episodic memory in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and amnesiac mild cognitive impairment (the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s when people start to have symptoms).

Researchers readily tick off studies needed to explore, clarify and validate existing NIBS data. What is the optimal stimulus session frequency, spacing and duration? How intense should the stimulus be and where should it be targeted for what effect? How might genetics or degree of brain impairment affect responsiveness? Would adjunct medication or cognitive training boost positive results? Could administering the stimulus while someone sleeps expedite memory consolidation?

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain.

While Sandrini’s review reported improvements induced by tES in the recall or recognition of words and images, there is no evidence it will translate into improvements in daily activities. This is another question that will require more research and testing, Sandrini notes.

Scientists are still lacking so much fundamental knowledge about the brain and how it works, says Reinhart. “We don’t know how information is represented in the brain or how it’s carried forward in time. It’s more complex than physics.”

Where the science is headed

Learning how to apply precision medicine to NIBS is the next focus in advancing this technology, says Shankar Tumati, a post-doctoral fellow working with Lanctôt.

There is great variability in each person’s brain anatomy—the thickness of the skull, the brain’s unique folds, the amount of cerebrospinal fluid. All of these structural differences impact how electrical or magnetic stimulation is distributed in the brain and ultimately the effects.

Using MRI or another brain scan along with computational modeling of the current flow, a clinician could create a treatment that is customized to each person’s brain, from where to put the electrodes to determining the exact dose and duration of stimulation needed to achieve lasting results, Sandrini says.

Above all, most neuroscientists say that largescale research studies over long periods of time are necessary to confirm the safety and durability of this therapy for the purpose of boosting memory. Short of that, there can be no FDA approval or medical regulation for this clinical use.

Lanctôt urges people to seek out clinical NIBS trials in their area if they want to see the science advance. “That is how we’ll find the answers,” she says, predicting it will be 5 to 10 years to develop each additional clinical application of NIBS. Ultimately, she predicts that reigning in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment will require a multi-pronged approach that includes lifestyle and medications, too.

Sandrini believes that scientific efforts should focus on preventing or delaying Alzheimer’s. “We need to start intervention earlier—as soon as people start to complain about forgetting things,” he says. “Changes in the brain start 10 years before [there is a problem]. Once Alzheimer’s develops, it is too late.”