A 3D-printed tongue reveals why chocolate tastes so good—and how to reduce its fat

Researchers are looking to engineer chocolate with less oil, which could reduce some of its detriments to health.

Creamy milk with velvety texture. Dark with sprinkles of sea salt. Crunchy hazelnut-studded chunks. Chocolate is a treat that appeals to billions of people worldwide, no matter the age. And it’s not only the taste, but the feel of a chocolate morsel slowly melting in our mouths—the smoothness and slipperiness—that’s part of the overwhelming satisfaction. Why is it so enjoyable?

That’s what an interdisciplinary research team of chocolate lovers from the University of Leeds School of Food Science and Nutrition and School of Mechanical Engineering in the U.K. resolved to study in 2021. They wanted to know, “What is making chocolate that desirable?” says Siavash Soltanahmadi, one of the lead authors of a new study about chocolates hedonistic quality.

Besides addressing the researchers’ general curiosity, their answers might help chocolate manufacturers make the delicacy even more enjoyable and potentially healthier. After all, chocolate is a billion-dollar industry. Revenue from chocolate sales, whether milk or dark, is forecasted to grow 13 percent by 2027 in the U.K. In the U.S., chocolate and candy sales increased by 11 percent from 2020 to 2021, on track to reach $44.9 billion by 2026. Figuring out how chocolate affects the human palate could up the ante even more.

Building a 3D tongue

The team began by building a 3D tongue to analyze the physical process by which chocolate breaks down inside the mouth.

As part of the effort, reported earlier this year in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the team studied a large variety of human tongues with the intention to build an “average” 3D model, says Soltanahmadi, a lubrication scientist. When it comes to edible substances, lubrication science looks at how food feels in the mouth and can help design foods that taste better and have more satisfying texture or health benefits.

There are variations in how people enjoy chocolate; some chew it while others “lick it” inside their mouths.

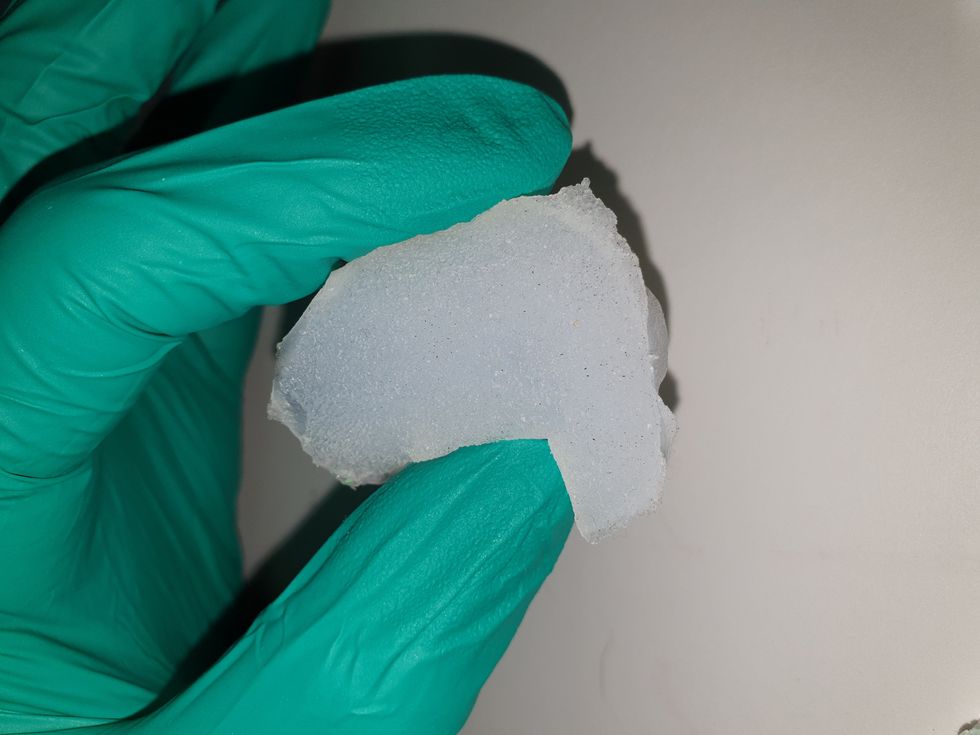

Tongue impressions from human participants studied using optical imaging helped the team build a tongue with key characteristics. “Our tongue is not a smooth muscle, it’s got some texture, it has got some roughness,” Soltanahmadi says. From those images, the team came up with a digital design of an average tongue and, using 3D printed molds, built a “mimic tongue.” They also added elastomers—such as silicone or polyurethane—to mimic the roughness, the texture and the mechanical properties of a real tongue. “Wettability" was another key component of the 3D tongue, Soltanahmadi says, referring to whether a surface mixes with water (hydrophilic) or, in the case of oil, resists it (hydrophobic).

Notably, the resulting artificial 3D-tongues looked nothing like the human version, but they were good mimics. The scientists also created “testing kits” that produced data on various physical parameters. One such parameter was viscosity, the measure of how gooey a food or liquid is — honey is more viscous compared to water, for example. Another was tribology, which defines how slippery something is — high fat yogurt is more slippery than low fat yogurt; milk can be more slippery than water. The researchers then mixed chocolate with artificial saliva and spread it on the 3D tongue to measure the tribology and the viscosity. From there they were able to study what happens inside the mouth when we eat chocolate.

The team focused on the stages of lubrication and the location of the fat in the chocolate, a process that has rarely been researched.

The artificial 3D-tongues look nothing like human tongues, but they function well enough to do the job.

Courtesy Anwesha Sarkar and University of Leeds

The oral processing of chocolate

We process food in our mouths in several stages, Soltanahmadi says. And there is variation in these stages depending on the type of food. So, the oral processing of a piece of meat would be different from, say, the processing of jelly or popcorn.

There are variations with chocolate, in particular; some people chew it while others use their tongues to explore it (within their mouths), Soltanahmadi explains. “Usually, from a consumer perspective, what we find is that if you have a luxury kind of a chocolate, then people tend to start with licking the chocolate rather than chewing it.” The researchers used a luxury brand of dark chocolate and focused on the process of licking rather than chewing.

As solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave.

Understanding the make-up of the chocolate was also an important step in the study. “Chocolate is a composite material. So, it has cocoa butter, which is oil, it has some particles in it, which is cocoa solid, and it has sugars," Soltanahmadi says. "Dark chocolate has less oil, for example, and less sugar in it, most of the time."

The researchers determined that the oral processing of chocolate begins as soon as it enters a person’s mouth; it starts melting upon exposure to one’s body temperature, even before the tongue starts moving, Soltanahmadi says. Then, lubrication begins. “[Saliva] mixes with the oily chocolate and it makes an emulsion." An emulsion is a fluid with a watery (or aqueous) phase and an oily phase. As chocolate breaks down in the mouth, that solid piece turns into a smooth emulsion with a fatty film. “The oil from the chocolate becomes droplets in a continuous aqueous phase,” says Soltanahmadi. In other words, as solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette, creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave, says Soltanahmadi.

Finding the sweet spot

After determining how chocolate is orally processed, the research team wanted to find the exact sweet spot of the breakdown of solid cocoa particles and fat as they are released into the mouth. They determined that the epicurean pleasure comes only from the chocolate's outer layer of fat; the secondary fatty layers inside the chocolate don’t add to the sensation. It was this final discovery that helped the team determine that it might be possible to produce healthier chocolate that would contain less oil, says Soltanahmadi. And therefore, less fat.

Rongjia Tao, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia, thinks the Leeds study and the concept behind it is “very interesting.” Tao, himself, did a study in 2016 and found he could reduce fat in milk chocolate by 20 percent. He believes that the Leeds researchers’ discovery about the first layer of fat being more important for taste than the other layer can inform future chocolate manufacturing. “As a scientist I consider this significant and an important starting point,” he says.

Chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research found that plant polyphenols can protect against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular ad neurodegenerative diseases.

Not everyone thinks it’s a good idea, such as chef Michael Antonorsi, founder and owner of Chuao Chocolatier, one of the leading chocolate makers in the U.S. First, he says, “cacao fat is definitely a good fat.” Second, he’s not thrilled that science is trying to interfere with nature. “Every time we've tried to intervene and change nature, we get things out of balance,” says Antonorsi. “There’s a reason cacao is botanically known as food of the gods. The botanical name is the Theobroma cacao: Theobroma in ancient Greek, Theo is God and Brahma is food. So it's a food of the gods,” Antonorsi explains. He’s doubtful that a chocolate made only with a top layer of fat will produce the same epicurean satisfaction. “You're not going to achieve the same sensation because that surface fat is going to dissipate and there is no fat from behind coming to take over,” he says.

Without layers of fat, Antonorsi fears the deeply satisfying experiential part of savoring chocolate will be lost. The University of Leeds team, however, thinks that it may be possible to make chocolate healthier - when consumed in limited amounts - without sacrificing its taste. They believe the concept of less fatty but no less slick chocolate will resonate with at least some chocolate-makers and consumers, too.

Chocolate already contains some healthful compounds. Its cocoa particles have “loads of health benefits,” says Soltanahmadi. Dark chocolate usually has more cocoa than milk chocolate. Some experts recommend that dark chocolate should contain at least 70 percent cocoa in order for it to offer some health benefit. Research has shown that the cocoa in chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research has shown that consuming plant polyphenols can be protective against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

“So keeping the healthy part of it and reducing the oily part of it, which is not healthy, but is giving you that indulgence of it … that was the final aim,” Soltanahmadi says. He adds that the team has been approached by individuals in the chocolate industry about their research. “Everyone wants to have a healthy chocolate, which at the same time tastes brilliant and gives you that self-indulging experience.”

After spaceflight record, NASA looks to protect astronauts on even longer trips

NASA astronaut Frank Rubio floats by the International Space Station’s “window to the world.” Yesterday, he returned from the longest single spaceflight by a U.S. astronaut on record - over one year. Exploring deep space will require even longer missions.

At T-minus six seconds, the main engines of the Atlantis Space Shuttle ignited, rattling its capsule “like a skyscraper in an earthquake,” according to astronaut Tom Jones, describing the 1988 launch. As the rocket lifted off and accelerated to three times the force of Earth's gravity, “It felt as if two of my friends were standing on my chest and wouldn’t get off.” But when Atlantis reached orbit, the main engines cut off, and the astronauts were suddenly weightless.

Since 1961, NASA has sent hundreds of astronauts into space while working to making their voyages safer and smoother. Yet, challenges remain. Weightlessness may look amusing when watched from Earth, but it has myriad effects on cognition, movement and other functions. When missions to space stretch to six months or longer, microgravity can impact astronauts’ health and performance, making it more difficult to operate their spacecraft.

Yesterday, NASA astronaut Frank Rubio returned to Earth after over one year, the longest single spaceflight for a U.S. astronaut. But this is just the start; longer and more complex missions into deep space loom ahead, from returning to the moon in 2025 to eventually sending humans to Mars. To ensure that these missions succeed, NASA is increasing efforts to study the biological effects and prevent harm.

The dangers of microgravity are real

A NASA report published in 2016 details a long list of incidents and near-misses caused – at least partly – by space-induced changes in astronauts’ vision and coordination. These issues make it harder to move with precision and to judge distance and velocity.

According to the report, in 1997, a resupply ship collided with the Mir space station, possibly because a crew member bumped into the commander during the final docking maneuver. This mishap caused significant damage to the space station.

Returns to Earth suffered from problems, too. The same report notes that touchdown speeds during the first 100 space shuttle landings were “outside acceptable limits. The fastest landing on record – 224 knots (258 miles) per hour – was linked to the commander’s momentary spatial disorientation.” Earlier, each of the six Apollo crews that landed on the moon had difficulty recognizing moon landmarks and estimating distances. For example, Apollo 15 landed in an unplanned area, ultimately straddling the rim of a five-foot deep crater on the moon, harming one of its engines.

Spaceflight causes unique stresses on astronauts’ brains and central nervous systems. NASA is working to reduce these harmful effects.

NASA

Space messes up your brain

In space, astronauts face the challenges of microgravity, ionizing radiation, social isolation, high workloads, altered circadian rhythms, monotony, confined living quarters and a high-risk environment. Among these issues, microgravity is one of the most consequential in terms of physiological changes. It changes the brain’s structure and its functioning, which can hurt astronauts’ performance.

The brain shifts upwards within the skull, displacing the cerebrospinal fluid, which reduces the brain’s cushioning. Essentially, the brain becomes crowded inside the skull like a pair of too-tight shoes.

That’s partly because of how being in space alters blood flow. On Earth, gravity pulls our blood and other internal fluids toward our feet, but our circulatory valves ensure that the fluids are evenly distributed throughout the body. In space, there’s not enough gravity to pull the fluids down, and they shift up, says Rachael D. Seidler, a physiologist specializing in spaceflight at the University of Florida and principal investigator on many space-related studies. The head swells and legs appear thinner, causing what astronauts call “puffy face chicken legs.”

“The brain changes at the structural and functional level,” says Steven Jillings, equilibrium and aerospace researcher at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. “The brain shifts upwards within the skull,” displacing the cerebrospinal fluid, which reduces the brain’s cushioning. Essentially, the brain becomes crowded inside the skull like a pair of too-tight shoes. Some of the displaced cerebrospinal fluid goes into cavities within the brain, called ventricles, enlarging them. “The remaining fluids pool near the chest and heart,” explains Jillings. After 12 consecutive months in space, one astronaut had a ventricle that was 25 percent larger than before the mission.

Some changes reverse themselves while others persist for a while. An example of a longer-lasting problem is spaceflight-induced neuro-ocular syndrome, which results in near-sightedness and pressure inside the skull. A study of approximately 300 astronauts shows near-sightedness affects about 60 percent of astronauts after long missions on the International Space Station (ISS) and more than 25 percent after spaceflights of only a few weeks.

Another long-term change could be the decreased ability of cerebrospinal fluid to clear waste products from the brain, Seidler says. That’s because compressing the brain also compresses its waste-removing glymphatic pathways, resulting in inflammation, vulnerability to injuries and worsening its overall health.

The effects of long space missions were best demonstrated on astronaut twins Scott and Mark Kelly. This NASA Twins Study showed multiple, perhaps permanent, changes in Scott after his 340-day mission aboard the ISS, compared to Mark, who remained on Earth. The differences included declines in Scott’s speed, accuracy and cognitive abilities that persisted longer than six months after returning to Earth in March 2016.

By the end of 2020, Scott’s cognitive abilities improved, but structural and physiological changes to his eyes still remained, he said in a BBC interview.

“It seems clear that the upward shift of the brain and compression of the surrounding tissues with ventricular expansion might not be a good thing,” Seidler says. “But, at this point, the long-term consequences to brain health and human performance are not really known.”

NASA astronaut Kate Rubins conducts a session for the Neuromapping investigation.

NASA

Staying sharp in space

To investigate how prolonged space travel affects the brain, NASA launched a new initiative called the Complement of Integrated Protocols for Human Exploration Research (CIPHER). “CIPHER investigates how long-duration spaceflight affects both brain structure and function,” says neurobehavioral scientist Mathias Basner at the University of Pennsylvania, a principal investigator for several NASA studies. “Through it, we can find out how the brain adapts to the spaceflight environment and how certain brain regions (behave) differently after – relative to before – the mission.”

To do this, he says, “Astronauts will perform NASA’s cognition test battery before, during and after six- to 12-month missions, and will also perform the same test battery in an MRI scanner before and after the mission. We have to make sure we better understand the functional consequences of spaceflight on the human brain before we can send humans safely to the moon and, especially, to Mars.”

As we go deeper into space, astronauts cognitive and physical functions will be even more important. “A trip to Mars will take about one year…and will introduce long communication delays,” Seidler says. “If you are on that mission and have a problem, it may take eight to 10 minutes for your message to reach mission control, and another eight to 10 minutes for the response to get back to you.” In an emergency situation, that may be too late for the response to matter.

“On a mission to Mars, astronauts will be exposed to stressors for unprecedented amounts of time,” Basner says. To counter them, NASA is considering the continuous use of artificial gravity during the journey, and Seidler is studying whether artificial gravity can reduce the harmful effects of microgravity. Some scientists are looking at precision brain stimulation as a way to improve memory and reduce anxiety due to prolonged exposure to radiation in space.

Other scientists are exploring how to protect neural stem cells (which create brain cells) from radiation damage, developing drugs to repair damaged brain cells and protect cells from radiation.

To boldly go where no astronauts have gone before, they must have optimal reflexes, vision and decision-making. In the era of deep space exploration, the brain—without a doubt—is the final frontier.

Additionally, NASA is scrutinizing each aspect of the mission, including astronaut exercise, nutrition and intellectual engagement. “We need to give astronauts meaningful work. We need to stimulate their sensory, cognitive and other systems appropriately,” Basner says, especially given their extreme confinement and isolation. The scientific experiments performed on the ISS – like studying how microgravity affects the ability of tissue to regenerate is a good example.

“We need to keep them engaged socially, too,” he continues. The ISS crew, for example, regularly broadcasts from space and answers prerecorded questions from students on Earth, and can engage with social media in real time. And, despite tight quarters, NASA is ensuring the crew capsule and living quarters on the moon or Mars include private space, which is critical for good mental health.

Exploring deep space builds on a foundation that began when astronauts first left the planet. With each mission, scientists learn more about spaceflight effects on astronauts’ bodies. NASA will be using these lessons to succeed with its plans to build science stations on the moon and, eventually, Mars.

“Through internally and externally led research, investigations implemented in space and in spaceflight simulations on Earth, we are striving to reduce the likelihood and potential impacts of neurostructural changes in future, extended spaceflight,” summarizes NASA scientist Alexandra Whitmire. To boldly go where no astronauts have gone before, they must have optimal reflexes, vision and decision-making. In the era of deep space exploration, the brain—without a doubt—is the final frontier.

A newly discovered brain cell may lead to better treatments for cognitive disorders

Swiss researchers have found a type of brain cell that appears to be a hybrid of the two other main types — and it could lead to new treatments for brain disorders.

Swiss researchers have discovered a third type of brain cell that appears to be a hybrid of the two other primary types — and it could lead to new treatments for many brain disorders.

The challenge: Most of the cells in the brain are either neurons or glial cells. While neurons use electrical and chemical signals to send messages to one another across small gaps called synapses, glial cells exist to support and protect neurons.

Astrocytes are a type of glial cell found near synapses. This close proximity to the place where brain signals are sent and received has led researchers to suspect that astrocytes might play an active role in the transmission of information inside the brain — a.k.a. “neurotransmission” — but no one has been able to prove the theory.

A new brain cell: Researchers at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering and the University of Lausanne believe they’ve definitively proven that some astrocytes do actively participate in neurotransmission, making them a sort of hybrid of neurons and glial cells.

According to the researchers, this third type of brain cell, which they call a “glutamatergic astrocyte,” could offer a way to treat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other disorders of the nervous system.

“Its discovery opens up immense research prospects,” said study co-director Andrea Volterra.

The study: Neurotransmission starts with a neuron releasing a chemical called a neurotransmitter, so the first thing the researchers did in their study was look at whether astrocytes can release the main neurotransmitter used by neurons: glutamate.

By analyzing astrocytes taken from the brains of mice, they discovered that certain astrocytes in the brain’s hippocampus did include the “molecular machinery” needed to excrete glutamate. They found evidence of the same machinery when they looked at datasets of human glial cells.

Finally, to demonstrate that these hybrid cells are actually playing a role in brain signaling, the researchers suppressed their ability to secrete glutamate in the brains of mice. This caused the rodents to experience memory problems.

“Our next studies will explore the potential protective role of this type of cell against memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as its role in other regions and pathologies than those explored here,” said Andrea Volterra, University of Lausanne.

But why? The researchers aren’t sure why the brain needs glutamatergic astrocytes when it already has neurons, but Volterra suspects the hybrid brain cells may help with the distribution of signals — a single astrocyte can be in contact with thousands of synapses.

“Often, we have neuronal information that needs to spread to larger ensembles, and neurons are not very good for the coordination of this,” researcher Ludovic Telley told New Scientist.

Looking ahead: More research is needed to see how the new brain cell functions in people, but the discovery that it plays a role in memory in mice suggests it might be a worthwhile target for Alzheimer’s disease treatments.

The researchers also found evidence during their study that the cell might play a role in brain circuits linked to seizures and voluntary movements, meaning it’s also a new lead in the hunt for better epilepsy and Parkinson’s treatments.

“Our next studies will explore the potential protective role of this type of cell against memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease, as well as its role in other regions and pathologies than those explored here,” said Volterra.