A 3D-printed tongue reveals why chocolate tastes so good—and how to reduce its fat

Researchers are looking to engineer chocolate with less oil, which could reduce some of its detriments to health.

Creamy milk with velvety texture. Dark with sprinkles of sea salt. Crunchy hazelnut-studded chunks. Chocolate is a treat that appeals to billions of people worldwide, no matter the age. And it’s not only the taste, but the feel of a chocolate morsel slowly melting in our mouths—the smoothness and slipperiness—that’s part of the overwhelming satisfaction. Why is it so enjoyable?

That’s what an interdisciplinary research team of chocolate lovers from the University of Leeds School of Food Science and Nutrition and School of Mechanical Engineering in the U.K. resolved to study in 2021. They wanted to know, “What is making chocolate that desirable?” says Siavash Soltanahmadi, one of the lead authors of a new study about chocolates hedonistic quality.

Besides addressing the researchers’ general curiosity, their answers might help chocolate manufacturers make the delicacy even more enjoyable and potentially healthier. After all, chocolate is a billion-dollar industry. Revenue from chocolate sales, whether milk or dark, is forecasted to grow 13 percent by 2027 in the U.K. In the U.S., chocolate and candy sales increased by 11 percent from 2020 to 2021, on track to reach $44.9 billion by 2026. Figuring out how chocolate affects the human palate could up the ante even more.

Building a 3D tongue

The team began by building a 3D tongue to analyze the physical process by which chocolate breaks down inside the mouth.

As part of the effort, reported earlier this year in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the team studied a large variety of human tongues with the intention to build an “average” 3D model, says Soltanahmadi, a lubrication scientist. When it comes to edible substances, lubrication science looks at how food feels in the mouth and can help design foods that taste better and have more satisfying texture or health benefits.

There are variations in how people enjoy chocolate; some chew it while others “lick it” inside their mouths.

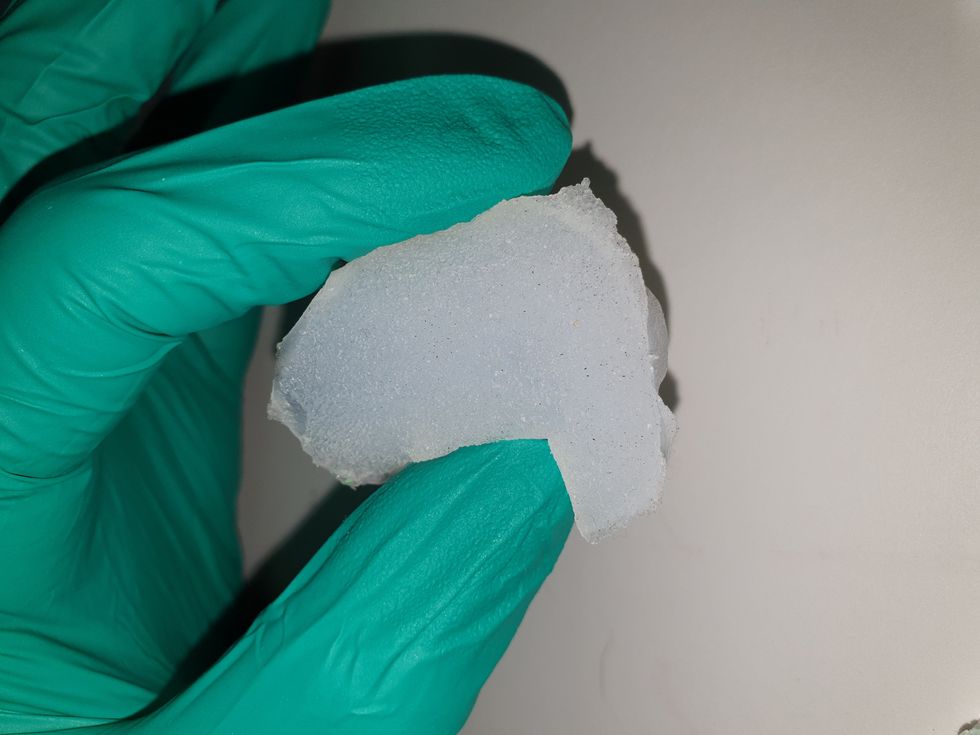

Tongue impressions from human participants studied using optical imaging helped the team build a tongue with key characteristics. “Our tongue is not a smooth muscle, it’s got some texture, it has got some roughness,” Soltanahmadi says. From those images, the team came up with a digital design of an average tongue and, using 3D printed molds, built a “mimic tongue.” They also added elastomers—such as silicone or polyurethane—to mimic the roughness, the texture and the mechanical properties of a real tongue. “Wettability" was another key component of the 3D tongue, Soltanahmadi says, referring to whether a surface mixes with water (hydrophilic) or, in the case of oil, resists it (hydrophobic).

Notably, the resulting artificial 3D-tongues looked nothing like the human version, but they were good mimics. The scientists also created “testing kits” that produced data on various physical parameters. One such parameter was viscosity, the measure of how gooey a food or liquid is — honey is more viscous compared to water, for example. Another was tribology, which defines how slippery something is — high fat yogurt is more slippery than low fat yogurt; milk can be more slippery than water. The researchers then mixed chocolate with artificial saliva and spread it on the 3D tongue to measure the tribology and the viscosity. From there they were able to study what happens inside the mouth when we eat chocolate.

The team focused on the stages of lubrication and the location of the fat in the chocolate, a process that has rarely been researched.

The artificial 3D-tongues look nothing like human tongues, but they function well enough to do the job.

Courtesy Anwesha Sarkar and University of Leeds

The oral processing of chocolate

We process food in our mouths in several stages, Soltanahmadi says. And there is variation in these stages depending on the type of food. So, the oral processing of a piece of meat would be different from, say, the processing of jelly or popcorn.

There are variations with chocolate, in particular; some people chew it while others use their tongues to explore it (within their mouths), Soltanahmadi explains. “Usually, from a consumer perspective, what we find is that if you have a luxury kind of a chocolate, then people tend to start with licking the chocolate rather than chewing it.” The researchers used a luxury brand of dark chocolate and focused on the process of licking rather than chewing.

As solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave.

Understanding the make-up of the chocolate was also an important step in the study. “Chocolate is a composite material. So, it has cocoa butter, which is oil, it has some particles in it, which is cocoa solid, and it has sugars," Soltanahmadi says. "Dark chocolate has less oil, for example, and less sugar in it, most of the time."

The researchers determined that the oral processing of chocolate begins as soon as it enters a person’s mouth; it starts melting upon exposure to one’s body temperature, even before the tongue starts moving, Soltanahmadi says. Then, lubrication begins. “[Saliva] mixes with the oily chocolate and it makes an emulsion." An emulsion is a fluid with a watery (or aqueous) phase and an oily phase. As chocolate breaks down in the mouth, that solid piece turns into a smooth emulsion with a fatty film. “The oil from the chocolate becomes droplets in a continuous aqueous phase,” says Soltanahmadi. In other words, as solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette, creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave, says Soltanahmadi.

Finding the sweet spot

After determining how chocolate is orally processed, the research team wanted to find the exact sweet spot of the breakdown of solid cocoa particles and fat as they are released into the mouth. They determined that the epicurean pleasure comes only from the chocolate's outer layer of fat; the secondary fatty layers inside the chocolate don’t add to the sensation. It was this final discovery that helped the team determine that it might be possible to produce healthier chocolate that would contain less oil, says Soltanahmadi. And therefore, less fat.

Rongjia Tao, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia, thinks the Leeds study and the concept behind it is “very interesting.” Tao, himself, did a study in 2016 and found he could reduce fat in milk chocolate by 20 percent. He believes that the Leeds researchers’ discovery about the first layer of fat being more important for taste than the other layer can inform future chocolate manufacturing. “As a scientist I consider this significant and an important starting point,” he says.

Chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research found that plant polyphenols can protect against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular ad neurodegenerative diseases.

Not everyone thinks it’s a good idea, such as chef Michael Antonorsi, founder and owner of Chuao Chocolatier, one of the leading chocolate makers in the U.S. First, he says, “cacao fat is definitely a good fat.” Second, he’s not thrilled that science is trying to interfere with nature. “Every time we've tried to intervene and change nature, we get things out of balance,” says Antonorsi. “There’s a reason cacao is botanically known as food of the gods. The botanical name is the Theobroma cacao: Theobroma in ancient Greek, Theo is God and Brahma is food. So it's a food of the gods,” Antonorsi explains. He’s doubtful that a chocolate made only with a top layer of fat will produce the same epicurean satisfaction. “You're not going to achieve the same sensation because that surface fat is going to dissipate and there is no fat from behind coming to take over,” he says.

Without layers of fat, Antonorsi fears the deeply satisfying experiential part of savoring chocolate will be lost. The University of Leeds team, however, thinks that it may be possible to make chocolate healthier - when consumed in limited amounts - without sacrificing its taste. They believe the concept of less fatty but no less slick chocolate will resonate with at least some chocolate-makers and consumers, too.

Chocolate already contains some healthful compounds. Its cocoa particles have “loads of health benefits,” says Soltanahmadi. Dark chocolate usually has more cocoa than milk chocolate. Some experts recommend that dark chocolate should contain at least 70 percent cocoa in order for it to offer some health benefit. Research has shown that the cocoa in chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research has shown that consuming plant polyphenols can be protective against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

“So keeping the healthy part of it and reducing the oily part of it, which is not healthy, but is giving you that indulgence of it … that was the final aim,” Soltanahmadi says. He adds that the team has been approached by individuals in the chocolate industry about their research. “Everyone wants to have a healthy chocolate, which at the same time tastes brilliant and gives you that self-indulging experience.”

New tech helps people of all ages stay social

Sonja Bauman, 39, and Mariela Florez, 83, taking one of their regular walks in Plantation, Fla. The pair met through an online platform called Papa that provides "family on demand." (Photo by Sonja Bauman)

In March, Sonja Bauman, 39, used an online platform called Papa, which offers “family on demand,” to meet Mariela Florez, an 83-year-old retiree. Despite living with her adult children, Florez was bored and lonely when they left for work, and her recoveries from a stroke and broken hip were going slowly. That's when Bauman began visiting twice per week. They take walks, strengthening Florez’s hip, and play games like Connect Four for mental stimulation. “It’s very important for me so I don’t feel lonely all day long,” said Florez. Her memories, blurred by the stroke, are gradually returning.

Papa is one of a growing number of tech approaches that are bringing together people of all ages. In addition to platforms like Papa that connect people in real life, other startups use virtual reality and video, with some of them focusing especially on deepening social connections between the generations — relationships that support the health of older and younger people alike. “I enjoy seeing Mariela as much as she enjoys seeing me,” Bauman said.

Connecting in real life

Telehealth expert Andrew Parker founded Papa in 2017 to improve the health outcomes of older adults and families. Seniors can meet people — some their grandkids’ age — for healthy activities, while working parents find retirees to watch their children. These “Papa Pals” are provided as a benefit through Medicare, Medicaid and some employer health plans.

In 2020, Papa connected Bauman, the 39-year-old Floridian, with another woman in her mid-70s who lives alone and has very limited mobility. Bauman began driving her to doctor’s appointments and helping her with chores around the house. “When I’m not there, she doesn’t leave her apartment,” said Bauman. The two have gone to the gym together, and they walk slowly through the neighborhood, chatting so it feels less like exercise.

Parker was driven to start Papa by the problem of social isolation among seniors, exacerbated by the pandemic, but he believes users of all ages can benefit. “Many of our Pals feel more comfortable opening up with older members than their same-aged friends,” he said.

Other platforms aim for similar, in-person connections. Generation Tech unites teens with seniors for technology training. And Mon Ami, which provides case management software for aging and disability service providers, has an app that connects isolated older people with college-age volunteers.

Making new connections through video

Several new sites match you with strangers for real-time video chatting on various topics, such as finding common ground on political issues. Other video platforms focus on intergenerational connections.

S. Jay Olshansky, a gerontology professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago, recalls the first time he saw Hyunseung Lee, an 11-year-old from Seoul, through his computer screen. The kid was shy, but Olshansky, 67, encouraged him to ask questions. “Turns out, he was thirsting for this kind of interaction.”

They’d connected through Eldera, a platform that pairs mentors age 60 and up with mentees, using an algorithm, for video conversations. “The time and wisdom of older adults is the most important natural resource we can give future generations,” said Dana Griffin, Eldera's CEO. “Connecting through a screen is the opposite of social media.”

In weekly meetings, Olshansky noticed Lee’s unique interest in math. “There’s something special in you,” Olshansky told him. “How do we bring it to the surface?” He suggested Lee write a book on his favorite subject, and the preteen ran with it, cranking out 70 pages in two weeks. Lee has published his love letter to theorems on Amazon.

Hyunseung Lee, age 11, of Korea, and U.S. college professor Jay Olshanksy, 67, discuss math, strategy and Hyunsung's budding career as a book author during their video chats through a platform called Eldera. (Photo by Dana Palmer/Eldera)

Lee’s parents told Olshansky that their son has become more assertive — a recurring theme, Griffin said. “Confidence is the number one thing parents tell us about.” Since Eldera’s inception last year, the number of mentors has grown exponentially. Even so, Griffin said the waitlist for mentors typically numbers 200 kids.

Another site, Big and Mini, hosts video interactions between seniors and young adults; about 10,000 active users have joined since 2019, said co-founder Aditi Merchant.

Users often bring the benefits of their video interactions to their real-world relationships. Olshansky views Lee as an older version of his grandkids. “Eldera teaches me how to interact with them.” Lee, high on confidence, began instructing his classmates in math. Griffin noted that a group of Eldera mentors in Memphis, who met initially on Eldera, now take walks together in-person to trade ideas for helping each other’s Eldera kids solve problems in their schools and communities.

“We’ve evolved into a community for older adults who want to give back to the world,” said Griffin. Other new tools for connection take the form of virtual reality apps.

Connecting in virtual reality

During pandemic isolation, record numbers of people bought devices for virtual and augmented reality. Such gadgets can convince you that you’re hanging out with friends, even if they’re in another hemisphere. Lifelike simulations from miles away could be especially useful for meaningful interactions between people of different generations, since they’re often geographically segregated.

VR’s benefits require further study, but users report less social isolation and depression, according to MIT research. The immersive, 3-D experience is more compelling than FaceTime or Zoom. “It’s like the difference between a phone call and video call,” said Rick Robinson, Vice President of AARP’s Innovation Labs.

“When VR is designed right, the medium disappears,” said Jeremy Bailenson of Stanford.

Dana Pierce, a 56-year-old government employee in Indiana, got Meta's VR headset in May, 2021, thinking she’d enjoy it more than a new laptop. After many virtual group tours of exotic destinations, she has no regrets. Her adventures occur on Alcove, an app made by Robinson’s Innovation Labs. He co-created it with VR-company Rendever and sought input from people over age 50 to tailor it to their interests. “I’m an introvert,” said Pierce. “I’ve been more socially active since getting my headset than I am in real life.”

Tagging along with her to places like Paris are avatars representing real people around the world. She’s gotten to know VR users in their 70s, 80s and 90s, as well as younger people and some her own age. One is a new friend she plays chess with in relaxing nature settings. Another is her oldest son. He lives 90 minutes away but, earlier this year, Pierce welcomed him and his girlfriend to her virtual house on Alcove. They chatted in the living room decorated with family photos uploaded by Pierce. Then they took out a boat to go VR fishing — because why not — until 2 a.m.

“When VR is designed right, the medium disappears,” said Jeremy Bailenson, a communications professor who directs Stanford’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab. He’s teaching a class of 175 students entirely in VR. After months of covid isolation, the first time the class met, “there was a big catharsis. It really feels like you’re in a big crowd.” Like-minded people meet in VR for events such as comedy shows and creative writing meetups, while the Swedish pop group ABBA has performed this year as digital versions of themselves (“ABBA-tars”) during a virtual concert tour.

Karen Fingerman, a psychologist and director of the Texas Aging and Longevity Center at the University of Texas-Austin, supports the idea of VR for social connection, though she added that some people need it more than others. Hospitals and assisted-living facilities are using products such as Penumbra’s REAL I-Series and MyndVR to bring VR excursions to isolated patients and seniors. “If you’re in a bed or facility, this gives you something to talk about,” said Gita Barry, Penumbra’s executive vice president.

Pierce uses it on most days. She may see another adult son, who lives with her, less often as a result. But VR helps her manage real-world stressors, more than escaping them. After a long workday, she visits her back porch on Alcove, which overlooks a pond. “It’s my little retreat,” she said. “VR improves my mood. It’s added a lot to my life.”

Some seniors are using more than one technology. Olshansky and Lee discuss strategy while playing Internet chess. And Olshansky recently began using VR. He sees his sister, who lives far away, in a virtual beach house. “It’d be a great way to interact with Hyunseung,” he said. “I should get him a headset.”

A version of this article first appeared in The Washington Post on December 3, 2021.

Friday Five: These boots were made for walking, even for people who can't

New boots could have you moving like Iron Man, based on research this month by Stanford scientists.

The Friday Five covers important stories in health and science research that you may have missed - usually over the previous week but, today, we're doing a lookback on breakthrough research over the month of October. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

This Friday Five episode covers the following studies published and announced over the past month:

- New boots could have you moving like Iron Man

- The problem with bedtime munching

- The perfect recipe for tiny brains

- The best sports for kids to avoid lifelong health risks

- Can virtual reality reduce pain?