A 3D-printed tongue reveals why chocolate tastes so good—and how to reduce its fat

Researchers are looking to engineer chocolate with less oil, which could reduce some of its detriments to health.

Creamy milk with velvety texture. Dark with sprinkles of sea salt. Crunchy hazelnut-studded chunks. Chocolate is a treat that appeals to billions of people worldwide, no matter the age. And it’s not only the taste, but the feel of a chocolate morsel slowly melting in our mouths—the smoothness and slipperiness—that’s part of the overwhelming satisfaction. Why is it so enjoyable?

That’s what an interdisciplinary research team of chocolate lovers from the University of Leeds School of Food Science and Nutrition and School of Mechanical Engineering in the U.K. resolved to study in 2021. They wanted to know, “What is making chocolate that desirable?” says Siavash Soltanahmadi, one of the lead authors of a new study about chocolates hedonistic quality.

Besides addressing the researchers’ general curiosity, their answers might help chocolate manufacturers make the delicacy even more enjoyable and potentially healthier. After all, chocolate is a billion-dollar industry. Revenue from chocolate sales, whether milk or dark, is forecasted to grow 13 percent by 2027 in the U.K. In the U.S., chocolate and candy sales increased by 11 percent from 2020 to 2021, on track to reach $44.9 billion by 2026. Figuring out how chocolate affects the human palate could up the ante even more.

Building a 3D tongue

The team began by building a 3D tongue to analyze the physical process by which chocolate breaks down inside the mouth.

As part of the effort, reported earlier this year in the scientific journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, the team studied a large variety of human tongues with the intention to build an “average” 3D model, says Soltanahmadi, a lubrication scientist. When it comes to edible substances, lubrication science looks at how food feels in the mouth and can help design foods that taste better and have more satisfying texture or health benefits.

There are variations in how people enjoy chocolate; some chew it while others “lick it” inside their mouths.

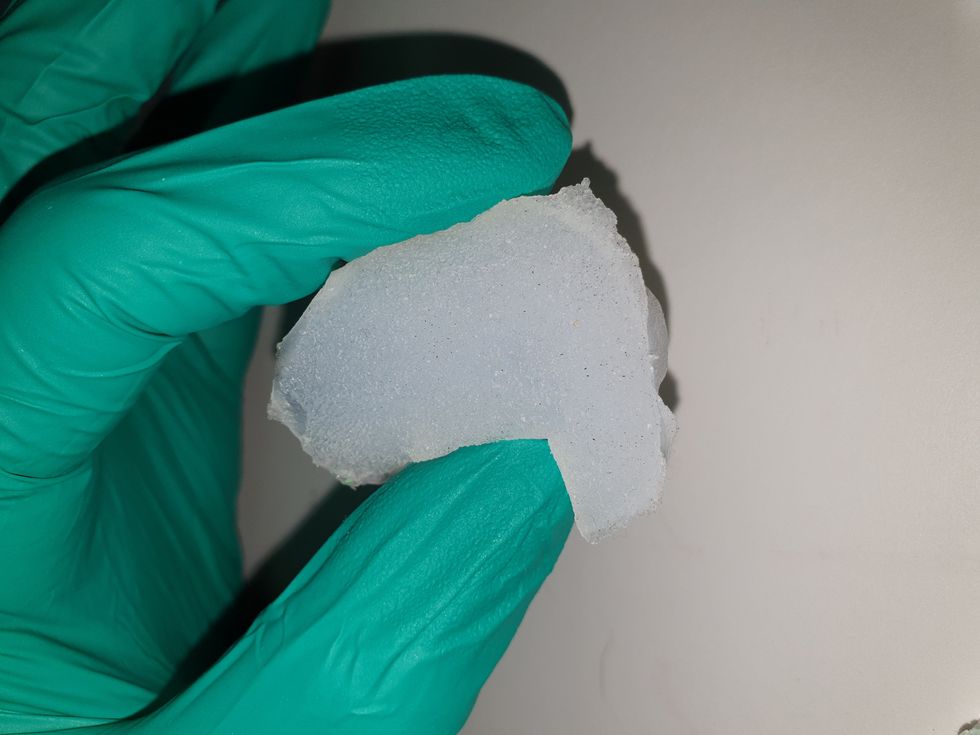

Tongue impressions from human participants studied using optical imaging helped the team build a tongue with key characteristics. “Our tongue is not a smooth muscle, it’s got some texture, it has got some roughness,” Soltanahmadi says. From those images, the team came up with a digital design of an average tongue and, using 3D printed molds, built a “mimic tongue.” They also added elastomers—such as silicone or polyurethane—to mimic the roughness, the texture and the mechanical properties of a real tongue. “Wettability" was another key component of the 3D tongue, Soltanahmadi says, referring to whether a surface mixes with water (hydrophilic) or, in the case of oil, resists it (hydrophobic).

Notably, the resulting artificial 3D-tongues looked nothing like the human version, but they were good mimics. The scientists also created “testing kits” that produced data on various physical parameters. One such parameter was viscosity, the measure of how gooey a food or liquid is — honey is more viscous compared to water, for example. Another was tribology, which defines how slippery something is — high fat yogurt is more slippery than low fat yogurt; milk can be more slippery than water. The researchers then mixed chocolate with artificial saliva and spread it on the 3D tongue to measure the tribology and the viscosity. From there they were able to study what happens inside the mouth when we eat chocolate.

The team focused on the stages of lubrication and the location of the fat in the chocolate, a process that has rarely been researched.

The artificial 3D-tongues look nothing like human tongues, but they function well enough to do the job.

Courtesy Anwesha Sarkar and University of Leeds

The oral processing of chocolate

We process food in our mouths in several stages, Soltanahmadi says. And there is variation in these stages depending on the type of food. So, the oral processing of a piece of meat would be different from, say, the processing of jelly or popcorn.

There are variations with chocolate, in particular; some people chew it while others use their tongues to explore it (within their mouths), Soltanahmadi explains. “Usually, from a consumer perspective, what we find is that if you have a luxury kind of a chocolate, then people tend to start with licking the chocolate rather than chewing it.” The researchers used a luxury brand of dark chocolate and focused on the process of licking rather than chewing.

As solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave.

Understanding the make-up of the chocolate was also an important step in the study. “Chocolate is a composite material. So, it has cocoa butter, which is oil, it has some particles in it, which is cocoa solid, and it has sugars," Soltanahmadi says. "Dark chocolate has less oil, for example, and less sugar in it, most of the time."

The researchers determined that the oral processing of chocolate begins as soon as it enters a person’s mouth; it starts melting upon exposure to one’s body temperature, even before the tongue starts moving, Soltanahmadi says. Then, lubrication begins. “[Saliva] mixes with the oily chocolate and it makes an emulsion." An emulsion is a fluid with a watery (or aqueous) phase and an oily phase. As chocolate breaks down in the mouth, that solid piece turns into a smooth emulsion with a fatty film. “The oil from the chocolate becomes droplets in a continuous aqueous phase,” says Soltanahmadi. In other words, as solid cocoa particles and fat are released, the emulsion envelops the tongue and coats the palette, creating a smooth feeling of chocolate all over the mouth. That tactile sensation is part of the chocolate’s hedonistic appeal we crave, says Soltanahmadi.

Finding the sweet spot

After determining how chocolate is orally processed, the research team wanted to find the exact sweet spot of the breakdown of solid cocoa particles and fat as they are released into the mouth. They determined that the epicurean pleasure comes only from the chocolate's outer layer of fat; the secondary fatty layers inside the chocolate don’t add to the sensation. It was this final discovery that helped the team determine that it might be possible to produce healthier chocolate that would contain less oil, says Soltanahmadi. And therefore, less fat.

Rongjia Tao, a physicist at Temple University in Philadelphia, thinks the Leeds study and the concept behind it is “very interesting.” Tao, himself, did a study in 2016 and found he could reduce fat in milk chocolate by 20 percent. He believes that the Leeds researchers’ discovery about the first layer of fat being more important for taste than the other layer can inform future chocolate manufacturing. “As a scientist I consider this significant and an important starting point,” he says.

Chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research found that plant polyphenols can protect against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular ad neurodegenerative diseases.

Not everyone thinks it’s a good idea, such as chef Michael Antonorsi, founder and owner of Chuao Chocolatier, one of the leading chocolate makers in the U.S. First, he says, “cacao fat is definitely a good fat.” Second, he’s not thrilled that science is trying to interfere with nature. “Every time we've tried to intervene and change nature, we get things out of balance,” says Antonorsi. “There’s a reason cacao is botanically known as food of the gods. The botanical name is the Theobroma cacao: Theobroma in ancient Greek, Theo is God and Brahma is food. So it's a food of the gods,” Antonorsi explains. He’s doubtful that a chocolate made only with a top layer of fat will produce the same epicurean satisfaction. “You're not going to achieve the same sensation because that surface fat is going to dissipate and there is no fat from behind coming to take over,” he says.

Without layers of fat, Antonorsi fears the deeply satisfying experiential part of savoring chocolate will be lost. The University of Leeds team, however, thinks that it may be possible to make chocolate healthier - when consumed in limited amounts - without sacrificing its taste. They believe the concept of less fatty but no less slick chocolate will resonate with at least some chocolate-makers and consumers, too.

Chocolate already contains some healthful compounds. Its cocoa particles have “loads of health benefits,” says Soltanahmadi. Dark chocolate usually has more cocoa than milk chocolate. Some experts recommend that dark chocolate should contain at least 70 percent cocoa in order for it to offer some health benefit. Research has shown that the cocoa in chocolate is rich in polyphenols, naturally occurring compounds also found in fruits and vegetables, such as grapes, apples and berries. Research has shown that consuming plant polyphenols can be protective against cancer, diabetes and osteoporosis as well as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

“So keeping the healthy part of it and reducing the oily part of it, which is not healthy, but is giving you that indulgence of it … that was the final aim,” Soltanahmadi says. He adds that the team has been approached by individuals in the chocolate industry about their research. “Everyone wants to have a healthy chocolate, which at the same time tastes brilliant and gives you that self-indulging experience.”

Researchers at Stanford have found that the virus that causes Covid-19 can infect fat cells, which could help explain why obesity is linked to worse outcomes for those who catch Covid-19.

Obesity is a risk factor for worse outcomes for a variety of medical conditions ranging from cancer to Covid-19. Most experts attribute it simply to underlying low-grade inflammation and added weight that make breathing more difficult.

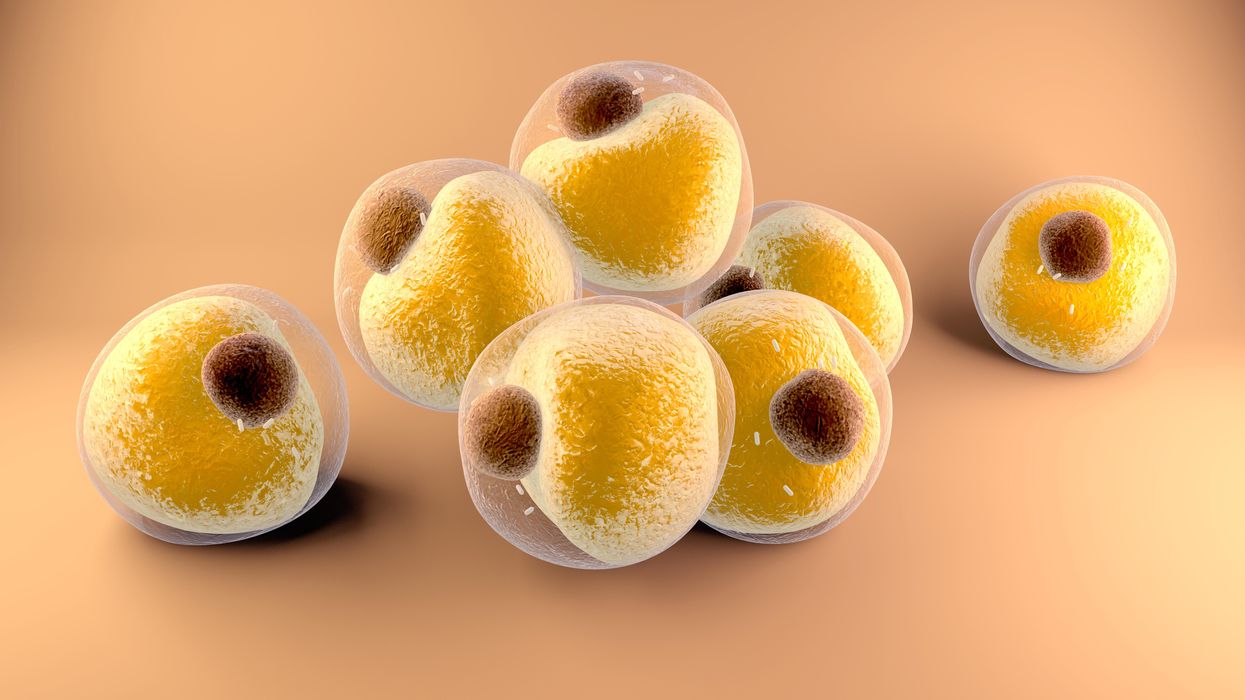

Now researchers have found a more direct reason: SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, can infect adipocytes, more commonly known as fat cells, and macrophages, immune cells that are part of the broader matrix of cells that support fat tissue. Stanford University researchers Catherine Blish and Tracey McLaughlin are senior authors of the study.

Most of us think of fat as the spare tire that can accumulate around the middle as we age, but fat also is present closer to most internal organs. McLaughlin's research has focused on epicardial fat, “which sits right on top of the heart with no physical barrier at all,” she says. So if that fat got infected and inflamed, it might directly affect the heart.” That could help explain cardiovascular problems associated with Covid-19 infections.

Looking at tissue taken from autopsy, there was evidence of SARS-CoV-2 virus inside the fat cells as well as surrounding inflammation. In fat cells and immune cells harvested from health humans, infection in the laboratory drove "an inflammatory response, particularly in the macrophages…They secreted proteins that are typically seen in a cytokine storm” where the immune response runs amok with potential life-threatening consequences. This suggests to McLaughlin “that there could be a regional and even a systemic inflammatory response following infection in fat.”

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

The macrophages studied by McLaughlin and Blish were spewing out inflammatory proteins, While the the virus within them was replicating, the new viral particles were not able to replicate within those cells. It was a different story in the fat cells. “When [the virus] gets into the fat cells, it not only replicates, it's a productive infection, which means the resulting viral particles can infect another cell,” including microphages, McLaughlin explains. It seems to be a symbiotic tango of the virus between the two cell types that keeps the cycle going.

It is easy to see how the airborne SARS-CoV-2 virus infects the nose and lungs, but how does it get into fat tissue? That is a mystery and the source of ample speculation.

Macrophages are mobile; they engulf and carry invading pathogens to lymphoid tissue in the lymph nodes, tonsils and elsewhere in the body to alert T cells of the immune system to the pathogen. Perhaps some of them also carry the virus through the bloodstream to more distant tissue.

ACE2 receptors are the means by which SARS-CoV-2 latches on to and enters most cells. They are not thought to be common on fat cells, so initially most researchers thought it unlikely they would become infected.

However, while some cell receptors always sit on the surface of the cell, other receptors are expressed on the surface only under certain conditions. Philipp Scherer, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Touchstone Diabetes Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, suggests that, in people who have obesity, “There might be higher levels of dysfunctional [fat cells] that facilitate entry of the virus,” either through transiently expressed ACE2 or other receptors. Inflammatory proteins generated by macrophages might contribute to this process.

Another hypothesis is that viral RNA might be smuggled into fat cells as cargo in small bits of material called extracellular vesicles, or EVs, that can travel between cells. Other researchers have shown that when EVs express ACE2 receptors, they can act as decoys for SARS-CoV-2, where the virus binds to them rather than a cell. These scientists are working to create drugs that mimic this decoy effect as an approach to therapy.

Do fat cells play a role in Long Covid? “Fat cells are a great place to hide. You have all the energy you need and fat cells turn over very slowly; they have a half-life of ten years,” says Scherer. Observational studies suggest that acute Covid-19 can trigger the onset of diabetes especially in people who are overweight, and that patients taking medicines to regulate their diabetes “were actually quite protective” against acute Covid-19. Scherer has funding to study the risks and benefits of those drugs in animal models of Long Covid.

McLaughlin says there are two areas of potential concern with fat tissue and Long Covid. One is that this tissue might serve as a “big reservoir where the virus continues to replicate and is sent out” to other parts of the body. The second is that inflammation due to infected fat cells and macrophages can result in fibrosis or scar tissue forming around organs, inhibiting their function. Once scar tissue forms, the tissue damage becomes more difficult to repair.

Current Covid-19 treatments work by stopping the virus from entering cells through the ACE2 receptor, so they likely would have no effect on virus that uses a different mechanism. That means another approach will have to be developed to complement the treatments we already have. So the best advice McLaughlin can offer today is to keep current on vaccinations and boosters and lose weight to reduce the risk associated with obesity.

Air pollution can lead to lung cancer. The connection suggests new ways to stop cancer in its tracks.

Researchers at Francis Crick Institute found that air pollution can "wake up" existing mutations, triggering them to turn into lung cancer. The scientists used their new understanding about this connection to prevent cancer in mice.

Forget taking a deep breath. Around the world, 99 percent of people breathe air polluted to unsafe levels, according to data from the World Health Organization. Activities such as burning fossil fuels release greenhouse gases that contribute to air pollution, which could lead to heart disease, stroke, asthma, emphysema, and some types of cancer.

“The burden of disease attributable to air pollution is now estimated to be on a par with other major global health risks such as unhealthy diet and tobacco smoking, and air pollution is now recognized as the single biggest environmental threat to human health,” wrote the authors of a 2021 WHO report.

The majority of lung cancer is attributed to smoking. But as pollution levels have increased, and anti-smoking campaigns have discouraged smoking, the proportion of lung cancers diagnosed in non-smokers has grown. The CDC estimates that 10 to 20 percent of lung cancers in the U.S. currently occur in non-smokers.

The mechanism between air pollution and the development of lung cancer has been unclear, but researchers at London’s Francis Crick Institute recently made an important breakthrough in understanding the connection. Lead investigator Charles Swanton presented this research last month at a conference in Paris.

Pollution awakens mutations

The Crick Institute scientists were able to identify a new link between common air pollutants and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). They focused on pollutants called particulate matter, or PM, that are 2.5 microns wide, narrower than human cells.

Most cancer diagnosed in non-smoking people is NSCLC, but this type of cancer hasn’t received the same research attention as more common lung cancers found in smokers, according to Clare Weeden, a cancer researcher at the Crick Institute and a co-author of the study.

“This is a really underserved and under-researched population that we really need to tackle, as well as lung cancers that occur in smokers,” she says. “Lung cancer is the number one cancer killer worldwide.”

In the past, some researchers believed air pollution caused mutations that led to cancer. Others believed these mutations could remain dormant without any detriment to health until pollutants or other stressors triggered them to become cancerous. Reviving the latter hypothesis that carcinogens may activate pre-existing mutations, instead of directly causing them, the Crick researchers analyzed samples from 463,679 people in the UK and parts of Asia, noting mutations and comparing changes in gene expression in mice and human cells.

“The mutation can exist in a nascent clone without causing cancer,” says Emilia Lim, a bioinformatics expert and a co-first author of the Crick study. “It is the carcinogen that promotes a conducive environment for this one little clone to grow and expand into cancer. Through our work, we were able to revive excitement for this hypothesis and bring it to light.”

The study explains a confusing pattern of lung cancer developing, particularly in women, despite a lack of environmental risk factors like smoking, secondhand smoke, or radon exposure. The culprit in these cases may have been too much PM 2.5 exposure.

Other researchers had previously identified a link between mutations in certain genes that control epidermal growth factor receptors, or EGFR mutations, and the development of NSCLC. In a 2019 study of 250 people with this type of cancer, about 32 percent had the mutation. Women are more likely to have EGFR mutations than men.

Not everyone who has the EGFR mutation will develop lung cancer. Respirologist Stephen Lam studies lung cancer at the BC Cancer Research Centre in Vancouver, Canada, but was not involved in the Crick Institute research. He says the study explains a confusing pattern of lung cancer developing, particularly in women, despite a lack of environmental risk factors like smoking, secondhand smoke, or radon exposure. The culprit in these cases may have been too much PM 2.5 exposure.

More exposure leads to inflammation and lesions

The Crick researchers found that an excess of PM 2.5 in the air sparked an inflammatory process in cells within the lung. This inflammation set the stage for NSCLC to develop in people and mice with existing EGFR mutations.

The researchers also exposed mice without EGFR mutations to PM 2.5 pollution—an experiment that couldn’t be ethically conducted in humans—to link pollution exposure to NSCLC. The mice experiments also showed that NSCLC is dose-dependent; higher levels of exposure were associated with higher number of cancerous lesions forming.

Ultimately, the study “fundamentally changed how we view lung cancer in people who have never smoked,” said Swanton in a Crick Institute press release. “Cells with cancer-causing mutations accumulate naturally as we age, but they are normally inactive. We’ve demonstrated that air pollution wakes these cells up in the lungs, encouraging them to grow and potentially form tumors.”

Preventing cancer before it begins

Targeted therapies already exist for people with EGFR mutations who’ve developed NSCLC, but they have many side effects, according to Weeden. Researchers hope that making more definitive links between pollutants and cancer could help prevent people with EGFR or other mutations from developing lung cancer in the first place.

Along those lines, as an additional component of their study presented last month, the Crick researchers were able to prevent cancer in mice that had the EGFR mutations by blocking inflammation. They used an antibody to inhibit a protein called interleukin 1 beta, which plays a key role in inflammation. Scientists could eventually use such antibodies or other therapies to make a drug treatment that people can take to stop cancer in its tracks, even if they live in highly polluted areas.

Such potential could reach beyond lung cancer; in the past, Crick and other researchers have also found associations between exposure to air pollution and mesothelioma, as well as cancers of the small intestine, lip, mouth, and throat. These links could be meaningful to a growing number of people as climate change intensifies, and with increases in air pollution from fossil fuel combustion and natural disasters like forest fires.

Plus, air pollution is just one external condition that can flip the switch of these inflammatory pathways. Identifying a link between pollution and cancer “has wide ramifications for many other environmental factors that may [play] similar roles,” Weedon says. She hopes that the Crick study and future research in this area will offer some hope for non-smokers frustrated by cancer diagnoses.