Scientists Are Growing an Edible Cholera Vaccine in Rice

The world's attention has been focused on the coronavirus crisis but Yemen, Bangladesh and many others countries in Asia and Africa are also in the grips of another pandemic: cholera. The current cholera pandemic first emerged in the 1970s and has devastated many communities in low-income countries. Each year, cholera is responsible for an estimated 1.3 million to 4 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths worldwide.

Immunologist Hiroshi Kiyono and his team at the University of Tokyo hope they can be part of the solution: They're making a cholera vaccine out of rice.

"It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot."

Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water that's contaminated by the feces of a person infected with the cholera bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria produces the cholera toxin in the intestines, leading to vomiting, diarrhea and severe dehydration. Cholera can kill within hours of infection if it if's not treated quickly.

Current cholera vaccines are mainly oral. The most common oral are given in two doses and are made out of animal or insect cells that are infected with killed or weakened cholera bacteria. Dukoral also includes cells infected with CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. Scientists grow cells containing the cholera bacteria and the CTB in bioreactors, large tanks in which conditions can be carefully controlled.

These cholera vaccines offer moderate protection but it wears off relatively quickly. Cold storage can also be an issue. The most common oral vaccines can be stored at room temperature but only for 14 days.

"Current vaccines confer around 60% efficacy over five years post-vaccination," says Lucy Breakwell, who leads the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's cholera work within Global Immunization Division. Given the limited protection, refrigeration issue, and the fact that current oral vaccines require two disease, delivery of cholera vaccines in a campaign or emergency setting can be challenging. "There is a need to develop and test new vaccines to improve public health response to cholera outbreaks."

A New Kind of Vaccine

Kiyono and scientists at Tokyo University are creating a new, plant-based cholera vaccine dubbed MucoRice-CTB. The researchers genetically modify rice so that it contains CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. The rice is crushed into a powder, mixed with saline solution and then drunk. The digestive tract is lined with mucosal membranes which contain the mucosal immune system. The mucosal immune system gets trained to recognize the cholera toxin as the rice passes through the intestines.

The cholera toxin has two main parts: the A subunit, which is harmful, and the B subunit, also known as CTB, which is nontoxic but allows the cholera bacteria to attach to gut cells. By inducing CTB-specific antibodies, "we might be able to block the binding of the vaccine toxin to gut cells, leading to the prevention of the toxin causing diarrhea," Kiyono says.

Kiyono studies the immune responses that occur at mucosal membranes across the body. He chose to focus on cholera because he wanted to replicate the way traditional vaccines work to get mucosal membranes in the digestive tract to produce an immune response. The difference is that his team is creating a food-based vaccine to induce this immune response. They are also solely focusing on getting the vaccine to induce antibodies for the cholera toxin. Since the cholera toxin is responsible for bacteria sticking to gut cells, the hope is that they can stop this process by producing antibodies for the cholera toxin. Current cholera vaccines target the cholera bacteria or both the bacteria and the toxin.

David Pascual, an expert in infectious diseases and immunology at the University of Florida, thinks that the MucoRice vaccine has huge promise. "I truly believe that the development of a food-based vaccine can be effective. CTB has a natural affinity for sampling cells in the gut to adhere, be processed, and then stimulate our immune system, he says. "In addition to vaccinating the gut, MucoRice has the potential to touch other mucosal surfaces in the mouth, which can help generate an immune response locally in the mouth and distally in the gut."

Cost Effectiveness

Kiyono says the MucoRice vaccine is much cheaper to produce than a traditional vaccine. Current vaccines need expensive bioreactors to grow cell cultures under very controlled, sterile conditions. This makes them expensive to manufacture, as different types of cell cultures need to be grown in separate buildings to avoid any chance of contamination. MucoRice doesn't require such an expensive manufacturing process because the rice plants themselves act as bioreactors.

The MucoRice vaccine also doesn't require the high cost of cold storage. It can be stored at room temperature for up to three years unlike traditional vaccines. "Plant-based vaccine development platforms present an exciting tool to reduce vaccine manufacturing costs, expand vaccine shelf life, and remove refrigeration requirements, all of which are factors that can limit vaccine supply and accessibility," Breakwell says.

Kathleen Hefferon, a microbiologist at Cornell University agrees. "It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot," she says. "The fact that it is made in rice means the vaccine can be stored for long periods on the shelf, without losing its activity."

A plant-based vaccine may even be able to address vaccine hesitancy, which has become a growing problem in recent years. Hefferon suggests that "using well-known food plants may serve to reduce the anxiety of some vaccine hesitant people."

Challenges of Plant Vaccines

Despite their advantages, no plant-based vaccines have been commercialized for human use. There are a number of reasons for this, ranging from the potential for too much variation in plants to the lack of facilities large enough to grow crops that comply with good manufacturing practices. Several plant vaccines for diseases like HIV and COVID-19 are in development, but they're still in early stages.

In developing the MucoRice vaccine, scientists at the University of Tokyo have tried to overcome some of the problems with plant vaccines. They've created a closed facility where they can grow rice plants directly in nutrient-rich water rather than soil. This ensures they can grow crops all year round in a space that satisfies regulations. There's also less chance for variation since the environment is tightly controlled.

Clinical Trials and Beyond

After successfully growing rice plants containing the vaccine, the team carried out their first clinical trial. It was completed early this year. Thirty participants received a placebo and 30 received the vaccine. They were all Japanese men between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. 60 percent produced antibodies against the cholera toxin with no side effects. It was a promising result. However, there are still some issues Kiyono's team need to address.

The vaccine may not provide enough protection on its own. The antigen in any vaccine is the substance it contains to induce an immune response. For the MucoRice vaccine, the antigen is not the cholera bacteria itself but the cholera toxin the bacteria produces.

"The development of the antigen in rice is innovative," says David Sack, a professor at John Hopkins University and expert in cholera vaccine development. "But antibodies against only the toxin have not been very protective. The major protective antigen is thought to be the LPS." LPS, or lipopolysaccharide, is a component of the outer wall of the cholera bacteria that plays an important role in eliciting an immune response.

The Japanese team is considering getting the rice to also express the O antigen, a core part of the LPS. Further investigation and clinical trials will look into improving the vaccine's efficacy.

Beyond cholera, Kiyono hopes that the vaccine platform could one day be used to make cost-effective vaccines for other pathogens, such as norovirus or coronavirus.

"We believe the MucoRice system may become a new generation of vaccine production, storage, and delivery system."

A model of a human kidney.

Science's dream of creating perfect custom organs on demand as soon as a patient needs one is still a long way off. But tiny versions are already serving as useful research tools and stepping stones toward full-fledged replacements.

Although organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, they are invaluable tools for research.

The Lowdown

Australian researchers have grown hundreds of mini human kidneys in the past few years. Known as organoids, they function much like their full-grown counterparts, minus a few features due to a lack of blood supply.

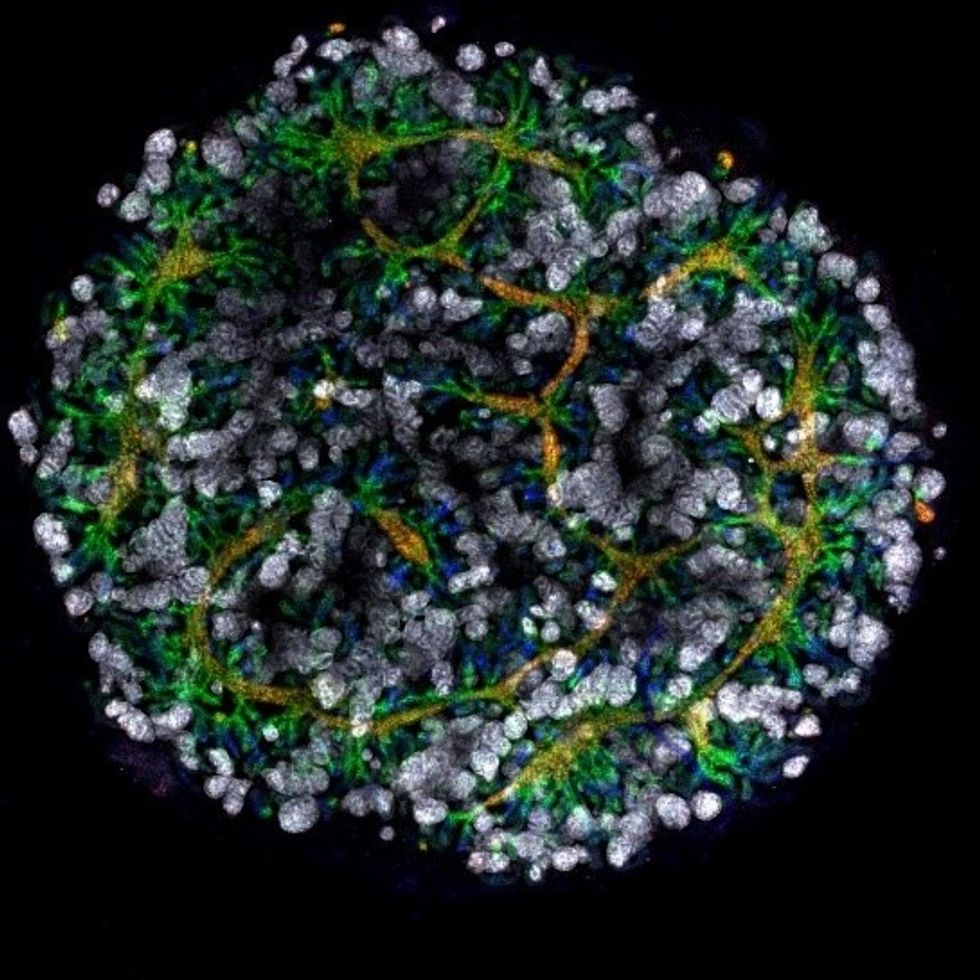

Cultivated in a petri dish, these kidneys are still a shadow of their human counterparts. They grow no larger than one-sixth of an inch in diameter; fully developed organs are up to five inches in length. They contain no more than a few dozen nephrons, the kidney's individual blood-filtering unit, whereas a fully-grown kidney has about 1 million nephrons. And the dish variety live for just a few weeks.

An organoid kidney created by the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, Australia.

Photo Credit: Shahnaz Khan.

But Melissa Little, head of the kidney research laboratory at the Murdoch Children's Institute in Melbourne, says these organoids are invaluable tools for research. Although renal failure is rare in children, more than half of those who suffer from such a disorder inherited it.

The mini kidneys enable scientists to better understand the progression of such disorders because they can be grown with a patient's specific genetic condition.

Mature stem cells can be extracted from a patient's blood sample and then reprogrammed to become like embryonic cells, able to turn into any type of cell in the body. It's akin to walking back the clock so that the cells regain unlimited potential for development. (The Japanese scientist who pioneered this technique was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2012.) These "induced pluripotent stem cells" can then be chemically coaxed to grow into mini kidneys that have the patient's genetic disorder.

"The (genetic) defects are quite clear in the organoids, and they can be monitored in the dish," Little says. To date, her research team has created organoids from 20 different stem cell lines.

Medication regimens can also be tested on the organoids, allowing specific tailoring for each patient. For now, such testing remains restricted to mice, but Little says it eventually will be done on human organoids so that the results can more accurately reflect how a given patient will respond to particular drugs.

Next Steps

Although these organoids cannot yet replace kidneys, Little says they may plug a huge gap in renal care by assisting in developing new treatments for chronic conditions. Currently, most patients with a serious kidney disorder see their options narrow to dialysis or organ transplantation. The former not only requires multiple sessions a week, but takes a huge toll on patient health.

Ten percent of older patients on dialysis die every year in the U.S. Aside from the physical trauma of organ transplantation, finding a suitable donor outside of a family member can be difficult.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells."

Meanwhile, the ongoing creation of organoids is supplying Little and her colleagues with enough information to create larger and more functional organs in the future. According to Little, researchers in the Netherlands, for example, have found that implanting organoids in mice leads to the creation of vascular growth, a potential pathway toward creating bigger and better kidneys.

And while Little acknowledges that creating a fully-formed custom organ is the ultimate goal, the mini organs are an important bridge step.

"This is just another great example of the potential of pluripotent stem cells, and I am just passionate to see it do some good."

Phil Gutis, an Alzheimer's patient who participated in a failed clinical trial, poses with his dog Abe.

Phil Gutis never had a stellar memory, but when he reached his early 50s, it became a problem he could no longer ignore. He had trouble calculating how much to tip after a meal, finding things he had just put on his desk, and understanding simple driving directions.

From 1998-2017, industry sources reported 146 failed attempts at developing Alzheimer's drugs.

So three years ago, at age 54, he answered an ad for a drug trial seeking people experiencing memory issues. He scored so low in the memory testing he was told something was wrong. M.R.I.s and PET scans confirmed that he had early-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Gutis, who is a former New York Times reporter and American Civil Liberties Union spokesman, felt fortunate to get into an advanced clinical trial of a new treatment for Alzheimer's disease. The drug, called aducanumab, had shown promising results in earlier studies.

Four years of data had found that the drug effectively reduced the burden of protein fragments called beta-amyloids, which destroy connections between nerve cells. Amyloid plaques are found in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease and are associated with impairments in thinking and memory.

Gutis eagerly participated in the clinical trial and received 35 monthly infusions. "For the first 20 infusions, I did not know whether I was receiving the drug or the placebo," he says. "During the last 15 months, I received aducanumab. But it really didn't matter if I was receiving the drug or the placebo because on March 21, the trial was stopped because [the drug company] Biogen found that the treatments were ineffective."

The news was devastating to the trial participants, but also to the Alzheimer's research community. Earlier this year, another pharmaceutical company, Roche, announced it was discontinuing two of its Alzheimer's clinical trials. From 1998-2017, industry sources reported 146 failed attempts at developing Alzheimer's drugs. There are five prescription drugs approved to treat its symptoms, but a cure remains elusive. The latest failures have left researchers scratching their heads about how to approach attacking the disease.

The failure of aducanumab was also another setback for the estimated 5.8 million people who have Alzheimer's in the United States. Of these, around 5.6 million are older than 65 and 200,000 suffer from the younger-onset form, including Gutis.

Gutis is understandably distraught about the cancellation of the trial. "I really had hopes it would work. So did all the patients."

While drug companies have failed so far, another group is stepping up to expedite the development of a cure: venture philanthropists.

For now, he is exercising every day to keep his blood flowing, which is supposed to delay the progression of the disease, and trying to eat a low-fat diet. "But I know that none of it will make a difference. Alzheimer's is a progressive disease. There are no treatments to delay it, let alone cure it."

But while drug companies have failed so far, another group is stepping up to expedite the development of a cure: venture philanthropists. These are successful titans of industry and dedicated foundations who are donating large sums of money to fill a much-needed void – funding research to look for new biomarkers.

Biomarkers are neurochemical indicators that can be used to detect the presence of a disease and objectively measure its progression. There are currently no validated biomarkers for Alzheimer's, but researchers are actively studying promising candidates. The hope is that they will find a reliable way to identify the disease even before the symptoms of mental decline show up, so that treatments can be directed at a very early stage.

Howard Fillit, Founding Executive Director and Chief Science Officer of the Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, says, "We need novel biomarkers to diagnose Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. But pharmaceutical companies don't put money into biomarkers research."

One of the venture philanthropists who has recently stepped up to the task is Bill Gates. In January 2018, he announced his father had Alzheimer's disease in an interview on the Today Show with Maria Shriver, whose father Sargent Shriver, died of Alzheimer's disease in 2011. Gates told Ms. Shriver that he had invested $100 million into Alzheimer's research, with $50 million of his donation going to Dementia Discovery Fund, which looks for new cures and treatments.

That August, Gates joined other investors in a new fund called Diagnostics Accelerator. The project aims to supports researchers looking to speed up new ideas for earlier and better diagnosis of the disease.

Gates and other donors committed more than $35 million to help launch it, and this April, Jeff and Mackenzie Bezos joined the coalition, bringing the current program funding to nearly $50 million.

"It makes sense that a challenge this significant would draw the attention of some of the world's leading thinkers."

None of these funders stand to make a profit on their donation, unlike traditional research investments by drug companies. The standard alternatives to such funding have upsides -- and downsides.

As Bill Gates wrote on his blog, "Investments from governments or charitable organizations are fantastic at generating new ideas and cutting-edge research -- but they're not always great at creating usable products, since no one stands to make a profit at the end of the day.

"Venture capital, on the other end of the spectrum, is more likely to develop a test that will reach patients, but its financial model favors projects that will earn big returns for investors. Venture philanthropy splits the difference. It incentivizes a bold, risk-taking approach to research with an end goal of a real product for real patients. If any of the projects backed by Diagnostics Accelerator succeed, our share of the financial windfall goes right back into the fund."

Gutis said he is thankful for any attention given to finding a cure for Alzheimer's.

"Most doctors and scientists will tell you that we're still in the dark ages when it comes to fully understanding how the brain works, let alone figuring out the cause or treatment for Alzheimer's.

"It makes sense that a challenge this significant would draw the attention of some of the world's leading thinkers. I only hope they can be more successful with their entrepreneurial approach to finding a cure than the drug companies have been with their more traditional paths."