Scientists Are Growing an Edible Cholera Vaccine in Rice

The world's attention has been focused on the coronavirus crisis but Yemen, Bangladesh and many others countries in Asia and Africa are also in the grips of another pandemic: cholera. The current cholera pandemic first emerged in the 1970s and has devastated many communities in low-income countries. Each year, cholera is responsible for an estimated 1.3 million to 4 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths worldwide.

Immunologist Hiroshi Kiyono and his team at the University of Tokyo hope they can be part of the solution: They're making a cholera vaccine out of rice.

"It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot."

Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water that's contaminated by the feces of a person infected with the cholera bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria produces the cholera toxin in the intestines, leading to vomiting, diarrhea and severe dehydration. Cholera can kill within hours of infection if it if's not treated quickly.

Current cholera vaccines are mainly oral. The most common oral are given in two doses and are made out of animal or insect cells that are infected with killed or weakened cholera bacteria. Dukoral also includes cells infected with CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. Scientists grow cells containing the cholera bacteria and the CTB in bioreactors, large tanks in which conditions can be carefully controlled.

These cholera vaccines offer moderate protection but it wears off relatively quickly. Cold storage can also be an issue. The most common oral vaccines can be stored at room temperature but only for 14 days.

"Current vaccines confer around 60% efficacy over five years post-vaccination," says Lucy Breakwell, who leads the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's cholera work within Global Immunization Division. Given the limited protection, refrigeration issue, and the fact that current oral vaccines require two disease, delivery of cholera vaccines in a campaign or emergency setting can be challenging. "There is a need to develop and test new vaccines to improve public health response to cholera outbreaks."

A New Kind of Vaccine

Kiyono and scientists at Tokyo University are creating a new, plant-based cholera vaccine dubbed MucoRice-CTB. The researchers genetically modify rice so that it contains CTB, a non-harmful part of the cholera toxin. The rice is crushed into a powder, mixed with saline solution and then drunk. The digestive tract is lined with mucosal membranes which contain the mucosal immune system. The mucosal immune system gets trained to recognize the cholera toxin as the rice passes through the intestines.

The cholera toxin has two main parts: the A subunit, which is harmful, and the B subunit, also known as CTB, which is nontoxic but allows the cholera bacteria to attach to gut cells. By inducing CTB-specific antibodies, "we might be able to block the binding of the vaccine toxin to gut cells, leading to the prevention of the toxin causing diarrhea," Kiyono says.

Kiyono studies the immune responses that occur at mucosal membranes across the body. He chose to focus on cholera because he wanted to replicate the way traditional vaccines work to get mucosal membranes in the digestive tract to produce an immune response. The difference is that his team is creating a food-based vaccine to induce this immune response. They are also solely focusing on getting the vaccine to induce antibodies for the cholera toxin. Since the cholera toxin is responsible for bacteria sticking to gut cells, the hope is that they can stop this process by producing antibodies for the cholera toxin. Current cholera vaccines target the cholera bacteria or both the bacteria and the toxin.

David Pascual, an expert in infectious diseases and immunology at the University of Florida, thinks that the MucoRice vaccine has huge promise. "I truly believe that the development of a food-based vaccine can be effective. CTB has a natural affinity for sampling cells in the gut to adhere, be processed, and then stimulate our immune system, he says. "In addition to vaccinating the gut, MucoRice has the potential to touch other mucosal surfaces in the mouth, which can help generate an immune response locally in the mouth and distally in the gut."

Cost Effectiveness

Kiyono says the MucoRice vaccine is much cheaper to produce than a traditional vaccine. Current vaccines need expensive bioreactors to grow cell cultures under very controlled, sterile conditions. This makes them expensive to manufacture, as different types of cell cultures need to be grown in separate buildings to avoid any chance of contamination. MucoRice doesn't require such an expensive manufacturing process because the rice plants themselves act as bioreactors.

The MucoRice vaccine also doesn't require the high cost of cold storage. It can be stored at room temperature for up to three years unlike traditional vaccines. "Plant-based vaccine development platforms present an exciting tool to reduce vaccine manufacturing costs, expand vaccine shelf life, and remove refrigeration requirements, all of which are factors that can limit vaccine supply and accessibility," Breakwell says.

Kathleen Hefferon, a microbiologist at Cornell University agrees. "It is much less expensive than a traditional vaccine, by a long shot," she says. "The fact that it is made in rice means the vaccine can be stored for long periods on the shelf, without losing its activity."

A plant-based vaccine may even be able to address vaccine hesitancy, which has become a growing problem in recent years. Hefferon suggests that "using well-known food plants may serve to reduce the anxiety of some vaccine hesitant people."

Challenges of Plant Vaccines

Despite their advantages, no plant-based vaccines have been commercialized for human use. There are a number of reasons for this, ranging from the potential for too much variation in plants to the lack of facilities large enough to grow crops that comply with good manufacturing practices. Several plant vaccines for diseases like HIV and COVID-19 are in development, but they're still in early stages.

In developing the MucoRice vaccine, scientists at the University of Tokyo have tried to overcome some of the problems with plant vaccines. They've created a closed facility where they can grow rice plants directly in nutrient-rich water rather than soil. This ensures they can grow crops all year round in a space that satisfies regulations. There's also less chance for variation since the environment is tightly controlled.

Clinical Trials and Beyond

After successfully growing rice plants containing the vaccine, the team carried out their first clinical trial. It was completed early this year. Thirty participants received a placebo and 30 received the vaccine. They were all Japanese men between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. 60 percent produced antibodies against the cholera toxin with no side effects. It was a promising result. However, there are still some issues Kiyono's team need to address.

The vaccine may not provide enough protection on its own. The antigen in any vaccine is the substance it contains to induce an immune response. For the MucoRice vaccine, the antigen is not the cholera bacteria itself but the cholera toxin the bacteria produces.

"The development of the antigen in rice is innovative," says David Sack, a professor at John Hopkins University and expert in cholera vaccine development. "But antibodies against only the toxin have not been very protective. The major protective antigen is thought to be the LPS." LPS, or lipopolysaccharide, is a component of the outer wall of the cholera bacteria that plays an important role in eliciting an immune response.

The Japanese team is considering getting the rice to also express the O antigen, a core part of the LPS. Further investigation and clinical trials will look into improving the vaccine's efficacy.

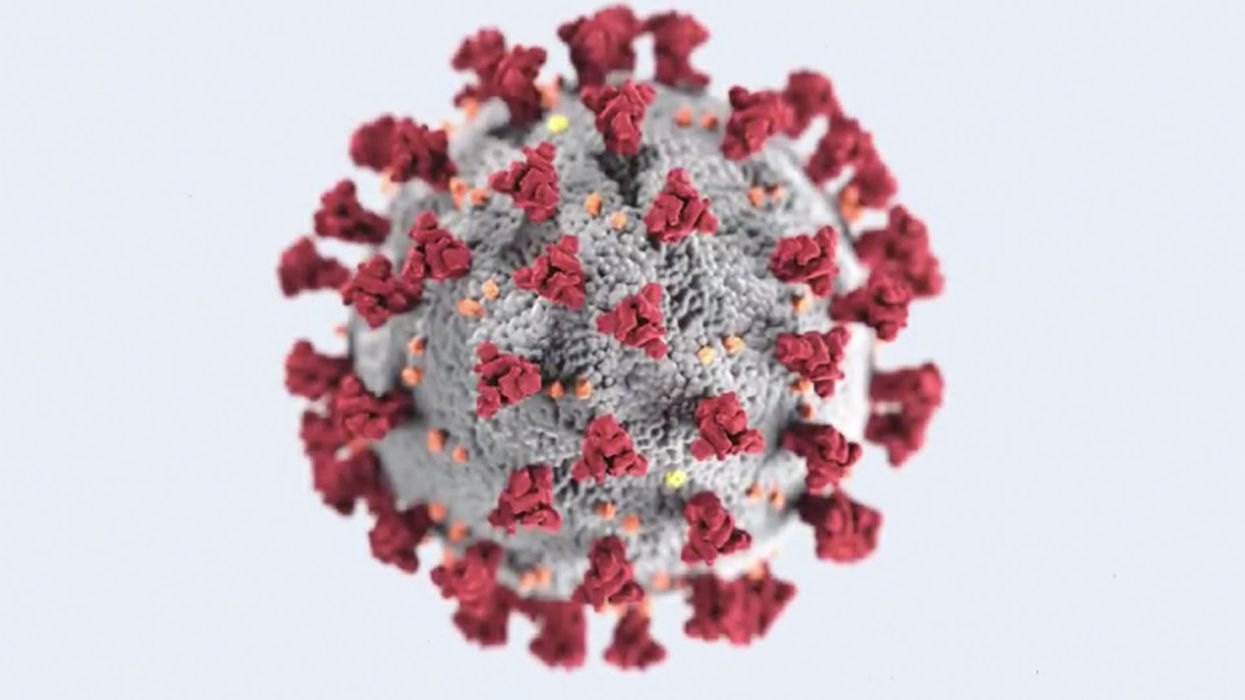

Beyond cholera, Kiyono hopes that the vaccine platform could one day be used to make cost-effective vaccines for other pathogens, such as norovirus or coronavirus.

"We believe the MucoRice system may become a new generation of vaccine production, storage, and delivery system."

Blood Donated from Recovered Coronavirus Patients May Soon Yield a Stopgap Treatment

Antibodies from the blood of recovered patients is being tested as a stopgap treatment.

In October 1918, Lieutenant L.W. McGuire of the United States Navy sent a report to the American Journal of Public Health detailing a promising therapy that had already saved the lives of a number of officers suffering from pneumonia complications due to the Spanish influenza outbreak.

"These antibodies then become essentially drugs."

McGuire described how transfusions of blood from recovered patients – an idea which had first been trialed during a polio epidemic in 1916 – had led to rapid recovery in a series of severe pneumonia cases at a Naval Hospital in Massachusetts. "It is believed the serum has a decided influence in shortening the course of the disease, and lowering the mortality," he wrote.

Now more than a century on, this treatment – long forgotten in the western world - is once again coming to the fore during the current COVID-19 pandemic. With fatalities continuing to rise, and no vaccine expected for many months, experts are urging medical centers across the U.S. and Europe to initiate collaborations between critical care and transfusion services to offer this as an emergency treatment for those who need it most.

As of March 20, there are more than 90,000 individuals globally who have recovered from the disease. Some scientists believe that the blood of many of these people contains high levels of neutralizing antibodies that can kill the virus.

"These antibodies then become essentially drugs," said Arturo Casadevall, professor of Molecular Microbiology & Immunology at John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who is currently co-ordinating a clinical trial of convalescent serum for COVID-19 involving 20 institutions across the US.

"We're talking about preparing a therapy right out of the serum of those that have recovered. It could also be used in patients who are already sick, but have not progressed to respiratory failure, to treat them before they enter intensive care units. That will provide a lot of support because there's a limited number of respirators and resources."

The first conclusive data on how the blood of recovered patients can help tackle COVID-19 is set to come out of China, where it was also used as an emergency treatment during the SARS and MERS outbreaks. On February 9, a severely ill patient in Wuhan was treated with convalescent serum and since then, hospitals across China have used the therapy on a total of 245 patients, with 91 reportedly showing an improvement in symptoms.

In China alone, more than 58,000 patients have now recovered from COVID-19. Casadevall said that last week the country shipped 90 tons of serum and plasma from these patients to Italy – the center of the pandemic in Europe – for emergency use.

Some of the first people to be treated are likely to be doctors and nurses in hospitals who are most at risk of exposure.

A current challenge, however, is that the blood donation from the recovered patients must be precisely timed in order to maximize the number of antibodies a future patient receives. Doctors in China say that obtaining the necessary blood samples at the right time is one of the major barriers to applying the treatment on a larger scale.

"It's difficult to get the donations," said Dr. Yuan Shi of Chongqing Medical University. "When patients have recovered from the disease, we would like to collect their blood two to four weeks afterwards. We try our best to call back the patients, but it's sometimes difficult to get them to come back within that time period."

Because of such hurdles, Japan's largest drugmaker, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, is now working to turn neutralizing antibodies from recovered COVID-19 patients into a standardized drug product. They hope to launch a clinical trial for this in the next few months.

In the U.S., Casadevall hopes blood transfusions from recovered patients can become clinically available as a therapy within the next four weeks, once regulatory approval has been received. Some of the first people to be treated are likely to be doctors and nurses in hospitals who are most at risk of exposure, to provide a protective boost in their immunity.

"A lot of healthcare workers in the U.S. have already been asked to quarantine, and you can imagine what effect that's going to have on the healthcare system," he said. "It can't take large numbers of people staying home; there's not the capacity."

But not all medical experts are convinced it's the way to go, especially when it comes to the most severe cases of COVID-19. "There's no knowing whether that treatment would be useful or not," warned Dr. Andrew Freedman, head of Cardiff University's School of Medicine in the U.K.

"There are going to be better things available in a few months, but we are facing, 'What do you do now?'"

However, Casadevall says that the treatment is not envisioned as a panacea to treating coronavirus, but simply a temporary measure which could give doctors some options until stronger options such as vaccines or new drugs are available.

"This is a stopgap option," he said. "There are going to be better things available in a few months, but we are facing, 'What do you do now?' The only thing we can offer severely ill people at the moment is respiratory support and oxygen, and we don't have anything to prevent those exposed from going on and getting ill."

Social distancing is a critical part of the strategy to defeat the novel coronavirus.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.