Elizabeth Holmes Through the Director’s Lens

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Elizabeth Holmes.

"The Inventor," a chronicle of Theranos's storied downfall, premiered recently on HBO. Leapsmag reached out to director Alex Gibney, whom The New York Times has called "one of America's most successful and prolific documentary filmmakers," for his perspective on Elizabeth Holmes and the world she inhabited.

Do you think Elizabeth Holmes was a charismatic sociopath from the start — or is she someone who had good intentions, over-promised, and began the lies to keep her business afloat, a "fake it till you make it" entrepreneur like Thomas Edison?

I'm not qualified to say if EH was or is a sociopath. I don't think she started Theranos as a scam whose only purpose was to make money. If she had done so, she surely would have taken more money for herself along the way. I do think that she had good intentions and that she, as you say, "began the lies to keep her business afloat." ([Reporter John] Carreyrou's book points out that those lies began early.) I think that the Edison comparison is instructive for a lot of reasons.

First, Edison was the original "fake-it-till-you-make-it" entrepreneur. That puts this kind of behavior in the mainstream of American business. By saying that, I am NOT endorsing the ethic, just the opposite. As one Enron executive mused about the mendacity there, "Was it fraud or was it bad marketing?" That gives you a sense of how baked-in the "fake it" sensibility is.

"Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals."

I think EH shares one other thing with Edison, which is a huge ego coupled with a talent for storytelling as long as she is the heroic, larger-than-life main character. It's interesting that EH calls her initial device "Edison." Edison was the world's most famous "inventor," both because of the devices that came out of his shop and and for his ability for "self-invention." As Randall Stross notes in "The Wizard of Menlo Park," he was the first celebrity businessman. In addition to her "good intentions," EH was certainly motivated by fame and glory and many of her lies were in service to those goals.

Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals. That doesn't excuse the lies. But those noble goals may have allowed EH to excuse them for herself or, more perniciously, to make believe that they weren't lies at all. This is where we get into scary psychological territory.

But rather than thinking of it as freakish, I think it's more productive to think of it as an exaggeration of the way we all lie to others and to ourselves. That's the point of including the Dan Ariely experiment with the dice. In that experiment, most of the subjects cheated more when they thought they were doing it for a good cause. Even more disturbing, that "good cause" allowed them to lie much more effectively because they had come to believe they weren't doing anything wrong. As it turns out, economics isn't a rational practice; it's the practice of rationalizing.

Where EH and Edison differ is that Edison had a firm grip on reality. He knew he could find a way to make the incandescent lightbulb work. There is no evidence that EH was close to making her "Edison" work. But rather than face reality (and possibly adjust her goals) she pretended that her dream was real. That kind of "over-promising" or "bold vision" is one thing when you are making a prototype in the lab. It's a far more serious matter when you are using a deeply flawed system on real patients. EH can tell herself that she had to do that (Walgreens was ready to walk away if she hadn't "gone live") or else Theranos would have run out of money.

But look at the calculation she made: she thought it was worth putting lives at risk in order to make her dream come true. Now we're getting into the realm of the sociopath. But my experience leads me to believe that -- as in the case of the Milgram experiment -- most people don't do terrible things right away, they come to crimes gradually as they become more comfortable with bigger and bigger rationalizations. At Theranos, the more valuable the company became, the bigger grew the lies.

The two whistleblowers come across as courageous heroes, going up against the powerful and intimidating company. The contrast between their youth and lack of power and the old elite backers of Theronos is staggering, and yet justice triumphed. Were the whistleblowers hesitant or afraid to appear in the film, or were they eager to share their stories?

By the time I got to them, they were willing and eager to tell their stories, once I convinced them that I would honor their testimony. In the case of Erika and Tyler, they were nudged to participate by John Carreyrou, in whom they had enormous trust.

"It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box."

Why do you think so many elite veterans of politics and venture capitalism succumbed to Holmes' narrative in the first place, without checking into the details of its technology or financials?

The reasons are all in the film. First, Channing Robertson and many of the old men on her board were clearly charmed by her and maybe attracted to her. They may have rationalized their attraction by convincing themselves it was for a good cause! Second, as Dan Ariely tells us, we all respond to stories -- more than graphs and data -- because they stir us emotionally. EH was a great storyteller. Third, the story of her as a female inventor and entrepreneur in male-dominated Silicon Valley is a tale that they wanted to invest in.

There may have been other factors. EH was very clever about the way she put together an ensemble of credibility. How could Channing Robertson, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis all be wrong? And when Walgreens put the Wellness Centers in stores, investors like Rupert Murdoch assumed that Walgreens must have done its due diligence. But they hadn't!

It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box. But that blind faith, as it turns out, is more a part of capitalism than we have been taught.

Do you think that Roger Parloff deserves any blame for the glowing Fortune story on Theranos, since he appears in the film to blame himself? Or was he just one more victim of Theranos's fraud?

He put her on the cover of Fortune so he deserves some blame for the fraud. He still blames himself. That willingness to hold himself to account shows how seriously he takes the job of a journalist. Unlike Elizabeth, Roger has the honesty and moral integrity to admit that he made a mistake. He owned up to it and published a mea culpa. That said, Roger was also a victim because Elizabeth lied to him.

Do you think investors in Silicon Valley, with their FOMO attitudes and deep pockets, are vulnerable to making the same mistake again with a shiny new startup, or has this saga been a sober reminder to do their due diligence first?

Many of the mistakes made with Theranos were the same mistakes made with Enron. We must learn to recognize that we are, by nature, trusting souls. Knowing that should lead us to a guiding slogan: "trust but verify."

The irony of Holmes dancing to "I Can't Touch This" is almost too perfect. How did you find that footage?

It was leaked to us.

"Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of 'The Apprentice.'"

Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for federal fraud charges, but Vanity Fair recently reported that she is seeking redemption, taking meetings with filmmakers for a possible documentary to share her "real" story. What do you think will become of Holmes in the long run?

It's usually a mistake to handicap a trial. My guess is that she will be convicted and do some prison time. But maybe she can convince jurors -- the way she convinced journalists, her board, and her investors -- that, on account of her noble intentions, she deserves to be found not guilty. "Somewhere, over the rainbow…"

After the trial, and possibly prison, I'm sure that EH will use her supporters (like Tim Draper) to find a way to use the virtual currency of her celebrity to rebrand herself and launch something new. Fitzgerald famously said that "there are no second acts in American lives." That may be the stupidest thing he ever said.

Donald Trump failed at virtually every business he ever embarked on. But he became a celebrity for being a fake businessman and used that celebrity -- and phony expertise -- to become president of the United States. Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of "The Apprentice." And then?

"You Can't Touch This!"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

A Rare Disease Just "Messed with the Wrong Mother." Now She's Fighting to Beat It Once and For All.

Amber Freed and Maxwell near their home in Denver, Colorado.

Amber Freed felt she was the happiest mother on earth when she gave birth to twins in March 2017. But that euphoric feeling began to fade over the next few months, as she realized her son wasn't making the same developmental milestones as his sister. "I had a perfect benchmark because they were twins, and I saw that Maxwell was floppy—he didn't have muscle tone and couldn't hold his neck up," she recalls. At first doctors placated her with statements that boys sometimes develop slower than girls, but the difference was just too drastic. At 10 month old, Maxwell had never reached to grab a toy. In fact, he had never even used his hands.

Thinking that perhaps Maxwell couldn't see well, Freed took him to an ophthalmologist who was the first to confirm her worst fears. He didn't find Maxwell to have vision problems, but he thought there was something wrong with the boy's brain. He had seen similar cases before and they always turned out to be rare disorders, and always fatal. "Start preparing yourself for your child not to live," he had said.

Getting the diagnosis took months of painful, invasive procedures, as well as fighting with the health insurance to get the genetic testing approved. Finally, in June 2018, doctors at the Children's Hospital Colorado gave the Freeds their son's diagnosis—a genetic mutation so rare it didn't even have a name, just a bunch of letters jammed together into a word SLC6A1—same as the name of the mutated gene. The mutation, with only 40 cases known worldwide at the time, caused developmental disabilities, movement and speech disorders, and a debilitating form of epilepsy.

The doctors didn't know much about the disorder, but they said that Maxwell would also regress in his development when he turned three or four. They couldn't tell how long he would live. "Hopefully you would become an expert and educate us about it," they said, as they gave Freed a five-page paper on the SLC6A1 and told her to start calling scientists if she wanted to help her son in any way. When she Googled the name, nothing came up. She felt horrified. "Our disease was too rare to care."

Freed's husband, a 6'2'' college football player broke down in sobs and she realized that if anything could be done to help Maxwell, she'd have be the one to do it. "I understood that I had to fight like a mother," she says. "And a determined mother can do a lot of things."

The Freed family.

Courtesy Amber Freed

She quit her job as an equity analyst the day of the diagnosis and became a full-time SLC6A1 citizen scientist looking for researchers studying mutations of this gene. In the wee hours of the morning, she called scientists in Europe. As the day progressed, she called researchers on the East Coast, followed by the West in the afternoon. In the evening, she switched to Asia and Australia. She asked them the same question. "Can you help explain my gene and how do we fix it?"

Scientists need money to do research, so Freed launched Milestones for Maxwell fundraising campaign, and a SLC6A1 Connect patient advocacy nonprofit, dedicated to improving the lives of children and families battling this rare condition. And then it became clear that the mutation wasn't as rare as it seemed. As other parents began to discover her nonprofit, the number of known cases rose from 40 to 100, and later to 400, Freed says. "The disease is only rare until it messes with the wrong mother."

It took one mother to find another to start looking into what's happening inside Maxwell's brain. Freed came across Jeanne Paz, a Gladstone Institutes researcher who studies epilepsy with particular interest in absence or silent seizures—those that don't manifest by convulsions, but rather make patients absently stare into space—and that's one type of seizures Maxwell has. "It's like a brief period of silence in the brain during which the person doesn't pay attention to what's happening, and as soon as they come out of the seizure they are back to life," Paz explains. "It's like a pause button on consciousness." She was working to understand the underlying biology.

To understand how seizures begin, spread and stop, Paz uses optogenetics in mice. From words "genetic" and "optikós," which means visible in Greek, the optogenetics technique involves two steps. First, scientists introduce a light-sensitive gene into a specific brain cell type—for example into excitatory neurons that release glutamate, a neurotransmitter, which activates other cells in the brain. Then they implant a very thin optical fiber into the brain area where they forged these light-sensitive neurons. As they shine the light through the optical fiber, researchers can make excitatory neurons to release glutamate—or instead tell them to stop being active and "shut up". The ability to control what these neurons of interest do, quite literally sheds light onto where seizures start, how they propagate and what cells are involved in stopping them.

"Let's say a seizure started and we shine the light that reduces the activity of specific neurons," Paz explains. "If that stops the seizure, we know that activating those cells was necessary to maintain the seizure." Likewise, shutting down their activity will make the seizure stop.

Freed reached out to Paz in 2019 and the two women had an instant connection. They were both passionate about brain and seizures research, even if for different reasons. Freed asked Paz if she would study her son's seizures and Paz agreed.

To do that, Paz needed mice that carried the SLC6A1 mutation, so Freed found a company in China that created them to specs. The company replaced a mouse SLC6A1 gene with a human mutated one and shipped them over to Paz's lab. "We call them Maxwell mice," Paz says, "and we are now implanting electrodes into them to see which brain regions generate seizures." That would help them understand what goes wrong and what brain cells are malfunctioning in the SLC6A1 mice—and help scientists better understand what might cause seizures in children.

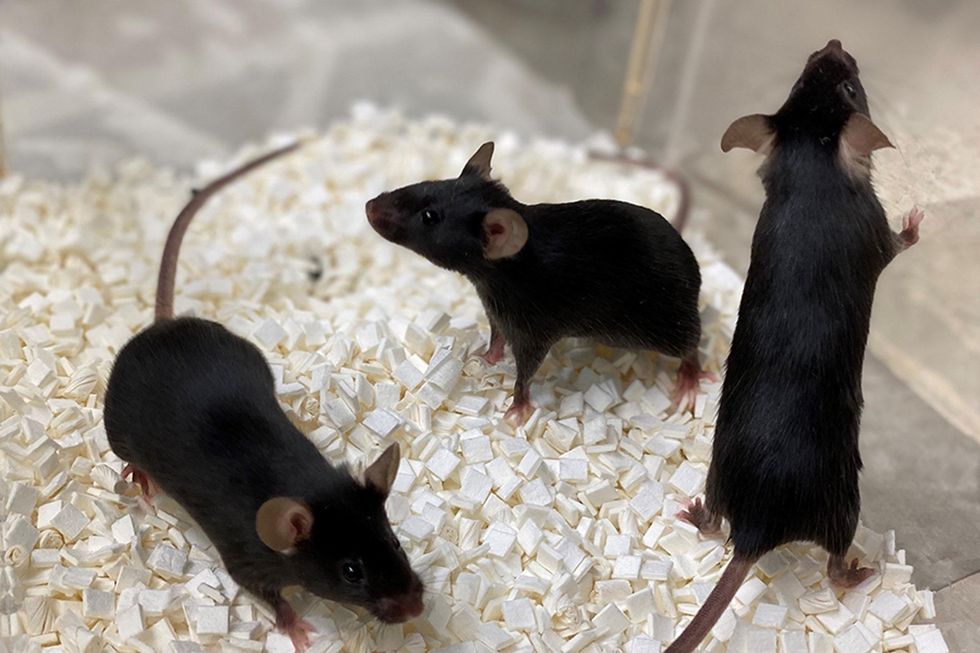

Bred to carry SLC6A1 mutation, these "Maxwell mice" will help better understand this debilitating genetic disease. (These mice are from Vanderbilt University, where researchers are also studying SLC6A1.)

Courtesy Amber Freed

This information—along with other research Amber is funding in other institutions—will inform the development of a novel genetic treatment, in which scientists would deploy a harmless virus to deliver a healthy, working copy of the SLC6A1 gene into the mice brains. They would likely deliver the therapeutic via a spinal tap infusion, and if it works and doesn't produce side effects in mice, the human trials will follow.

In the meantime, Freed is raising money to fund other research of various stop-gap measures. On April 22, 2021, she updated her Milestone for Maxwell page with a post that her nonprofit is funding yet another effort. It is a trial at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, in which doctors will use an already FDA-approved drug, which was recently repurposed for the SLC6A1 condition to treat epilepsy in these children. "It will buy us time," Freed says—while the gene therapy effort progresses.

Freed is determined to beat SLC6A1 before it beats down her family. She hopes to put an end to this disease—and similar genetic diseases—once and for all. Her goal is not only to have scientists create a remedy, but also to add the mutation to a newborn screening panel. That way, children born with this condition in the future would receive gene therapy before they even leave the hospital.

"I don't want there to be another Maxwell Freed," she says, "and that's why I am fighting like a mother." The gene therapy trial still might be a few years away, but the Weill Cornell one aims to launch very soon—possibly around Mother's Day. This is yet another milestone for Maxwell, another baby step forward—and the best gift a mother can get.

Lina Zeldovich has written about science, medicine and technology for Popular Science, Smithsonian, National Geographic, Scientific American, Reader’s Digest, the New York Times and other major national and international publications. A Columbia J-School alumna, she has won several awards for her stories, including the ASJA Crisis Coverage Award for Covid reporting, and has been a contributing editor at Nautilus Magazine. In 2021, Zeldovich released her first book, The Other Dark Matter, published by the University of Chicago Press, about the science and business of turning waste into wealth and health. You can find her on http://linazeldovich.com/ and @linazeldovich.

On May 13th, scientific and medical experts will discuss and answer questions about the vaccine for those under 16.

This virtual event convened leading scientific and medical experts to address the public's questions and concerns about Covid-19 vaccines in kids and teens. Highlight video below.

DATE:

Thursday, May 13th, 2021

12:30 p.m. - 1:45 p.m. EDT

Dr. H. Dele Davies, M.D., MHCM

Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs and Dean for Graduate Studies at the University of Nebraska Medical (UNMC). He is an internationally recognized expert in pediatric infectious diseases and a leader in community health.

Dr. Emily Oster, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics at Brown University. She is a best-selling author and parenting guru who has pioneered a method of assessing school safety.

Dr. Tina Q. Tan, M.D.

Professor of Pediatrics at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. She has been involved in several vaccine survey studies that examine the awareness, acceptance, barriers and utilization of recommended preventative vaccines.

Dr. Inci Yildirim, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc.

Associate Professor of Pediatrics (Infectious Disease); Medical Director, Transplant Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine; Associate Professor of Global Health, Yale Institute for Global Health. She is an investigator for the multi-institutional COVID-19 Prevention Network's (CoVPN) Moderna mRNA-1273 clinical trial for children 6 months to 12 years of age.

About the Event Series

This event is the second of a four-part series co-hosted by Leaps.org, the Aspen Institute Science & Society Program, and the Sabin–Aspen Vaccine Science & Policy Group, with generous support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

:

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.