Elizabeth Holmes Through the Director’s Lens

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Elizabeth Holmes.

"The Inventor," a chronicle of Theranos's storied downfall, premiered recently on HBO. Leapsmag reached out to director Alex Gibney, whom The New York Times has called "one of America's most successful and prolific documentary filmmakers," for his perspective on Elizabeth Holmes and the world she inhabited.

Do you think Elizabeth Holmes was a charismatic sociopath from the start — or is she someone who had good intentions, over-promised, and began the lies to keep her business afloat, a "fake it till you make it" entrepreneur like Thomas Edison?

I'm not qualified to say if EH was or is a sociopath. I don't think she started Theranos as a scam whose only purpose was to make money. If she had done so, she surely would have taken more money for herself along the way. I do think that she had good intentions and that she, as you say, "began the lies to keep her business afloat." ([Reporter John] Carreyrou's book points out that those lies began early.) I think that the Edison comparison is instructive for a lot of reasons.

First, Edison was the original "fake-it-till-you-make-it" entrepreneur. That puts this kind of behavior in the mainstream of American business. By saying that, I am NOT endorsing the ethic, just the opposite. As one Enron executive mused about the mendacity there, "Was it fraud or was it bad marketing?" That gives you a sense of how baked-in the "fake it" sensibility is.

"Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals."

I think EH shares one other thing with Edison, which is a huge ego coupled with a talent for storytelling as long as she is the heroic, larger-than-life main character. It's interesting that EH calls her initial device "Edison." Edison was the world's most famous "inventor," both because of the devices that came out of his shop and and for his ability for "self-invention." As Randall Stross notes in "The Wizard of Menlo Park," he was the first celebrity businessman. In addition to her "good intentions," EH was certainly motivated by fame and glory and many of her lies were in service to those goals.

Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals. That doesn't excuse the lies. But those noble goals may have allowed EH to excuse them for herself or, more perniciously, to make believe that they weren't lies at all. This is where we get into scary psychological territory.

But rather than thinking of it as freakish, I think it's more productive to think of it as an exaggeration of the way we all lie to others and to ourselves. That's the point of including the Dan Ariely experiment with the dice. In that experiment, most of the subjects cheated more when they thought they were doing it for a good cause. Even more disturbing, that "good cause" allowed them to lie much more effectively because they had come to believe they weren't doing anything wrong. As it turns out, economics isn't a rational practice; it's the practice of rationalizing.

Where EH and Edison differ is that Edison had a firm grip on reality. He knew he could find a way to make the incandescent lightbulb work. There is no evidence that EH was close to making her "Edison" work. But rather than face reality (and possibly adjust her goals) she pretended that her dream was real. That kind of "over-promising" or "bold vision" is one thing when you are making a prototype in the lab. It's a far more serious matter when you are using a deeply flawed system on real patients. EH can tell herself that she had to do that (Walgreens was ready to walk away if she hadn't "gone live") or else Theranos would have run out of money.

But look at the calculation she made: she thought it was worth putting lives at risk in order to make her dream come true. Now we're getting into the realm of the sociopath. But my experience leads me to believe that -- as in the case of the Milgram experiment -- most people don't do terrible things right away, they come to crimes gradually as they become more comfortable with bigger and bigger rationalizations. At Theranos, the more valuable the company became, the bigger grew the lies.

The two whistleblowers come across as courageous heroes, going up against the powerful and intimidating company. The contrast between their youth and lack of power and the old elite backers of Theronos is staggering, and yet justice triumphed. Were the whistleblowers hesitant or afraid to appear in the film, or were they eager to share their stories?

By the time I got to them, they were willing and eager to tell their stories, once I convinced them that I would honor their testimony. In the case of Erika and Tyler, they were nudged to participate by John Carreyrou, in whom they had enormous trust.

"It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box."

Why do you think so many elite veterans of politics and venture capitalism succumbed to Holmes' narrative in the first place, without checking into the details of its technology or financials?

The reasons are all in the film. First, Channing Robertson and many of the old men on her board were clearly charmed by her and maybe attracted to her. They may have rationalized their attraction by convincing themselves it was for a good cause! Second, as Dan Ariely tells us, we all respond to stories -- more than graphs and data -- because they stir us emotionally. EH was a great storyteller. Third, the story of her as a female inventor and entrepreneur in male-dominated Silicon Valley is a tale that they wanted to invest in.

There may have been other factors. EH was very clever about the way she put together an ensemble of credibility. How could Channing Robertson, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis all be wrong? And when Walgreens put the Wellness Centers in stores, investors like Rupert Murdoch assumed that Walgreens must have done its due diligence. But they hadn't!

It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box. But that blind faith, as it turns out, is more a part of capitalism than we have been taught.

Do you think that Roger Parloff deserves any blame for the glowing Fortune story on Theranos, since he appears in the film to blame himself? Or was he just one more victim of Theranos's fraud?

He put her on the cover of Fortune so he deserves some blame for the fraud. He still blames himself. That willingness to hold himself to account shows how seriously he takes the job of a journalist. Unlike Elizabeth, Roger has the honesty and moral integrity to admit that he made a mistake. He owned up to it and published a mea culpa. That said, Roger was also a victim because Elizabeth lied to him.

Do you think investors in Silicon Valley, with their FOMO attitudes and deep pockets, are vulnerable to making the same mistake again with a shiny new startup, or has this saga been a sober reminder to do their due diligence first?

Many of the mistakes made with Theranos were the same mistakes made with Enron. We must learn to recognize that we are, by nature, trusting souls. Knowing that should lead us to a guiding slogan: "trust but verify."

The irony of Holmes dancing to "I Can't Touch This" is almost too perfect. How did you find that footage?

It was leaked to us.

"Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of 'The Apprentice.'"

Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for federal fraud charges, but Vanity Fair recently reported that she is seeking redemption, taking meetings with filmmakers for a possible documentary to share her "real" story. What do you think will become of Holmes in the long run?

It's usually a mistake to handicap a trial. My guess is that she will be convicted and do some prison time. But maybe she can convince jurors -- the way she convinced journalists, her board, and her investors -- that, on account of her noble intentions, she deserves to be found not guilty. "Somewhere, over the rainbow…"

After the trial, and possibly prison, I'm sure that EH will use her supporters (like Tim Draper) to find a way to use the virtual currency of her celebrity to rebrand herself and launch something new. Fitzgerald famously said that "there are no second acts in American lives." That may be the stupidest thing he ever said.

Donald Trump failed at virtually every business he ever embarked on. But he became a celebrity for being a fake businessman and used that celebrity -- and phony expertise -- to become president of the United States. Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of "The Apprentice." And then?

"You Can't Touch This!"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Tech-related injuries are becoming more common as many people depend on - and often develop addictions for - smart phones and computers.

In the 1990s, a mysterious virus spread throughout the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Lab—or that’s what the scientists who worked there thought. More of them rubbed their aching forearms and massaged their cricked necks as new computers were introduced to the AI Lab on a floor-by-floor basis. They realized their musculoskeletal issues coincided with the arrival of these new computers—some of which were mounted high up on lab benches in awkward positions—and the hours spent typing on them.

Today, these injuries have become more common in a society awash with smart devices, sleek computers, and other gadgets. And we don’t just get hurt from typing on desktop computers; we’re massaging our sore wrists from hours of texting and Facetiming on phones, especially as they get bigger in size.

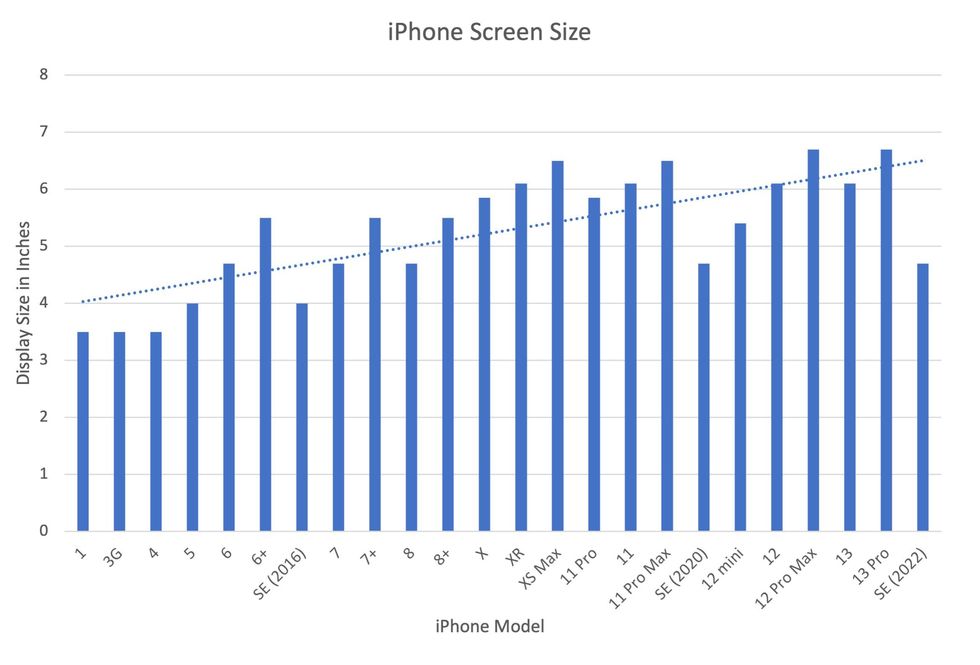

In 2007, the first iPhone measured 3.5-inches diagonally, a measurement known as the display size. That’s been nearly doubled by the newest iPhone 13 Pro, which has a 6.7-inch display. Other phones, too, like the Google Pixel 6 and the Samsung Galaxy S22, have bigger screens than their predecessors. Physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons have had to come up with names for a variety of new conditions: selfie elbow, tech neck, texting thumb. Orthopedic surgeon Sonya Sloan says she sees selfie elbow in younger kids and in women more often than men. She hears complaints related to technology once or twice a day.

The addictive quality of smartphones and social media means that people spend more time on their devices, which exacerbates injuries. According to Statista, 68 percent of those surveyed spent over three hours a day on their phone, and almost half spent five to six hours a day. Another report showed that people dedicate a third of their day to checking their phones, while the Media Effects Research Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University has found that bigger screens, ideal for entertainment purposes, immerse their users more than smaller screens. Oversized screens also provide easier navigation and more space for those with bigger hands or trouble seeing.

But others with conditions like arthritis can benefit from smaller phones. In March of 2016, Apple released the iPhone SE with a display size of 4.7 inches—an inch smaller than the iPhone 7, released that September. Apple has since come out with two more versions of the diminutive iPhone SE, one in 2020 and another in 2022.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance science journalist, has the Google Pixel 6. She was drawn to the phone because Google marketed the Pixel 6’s camera as better at capturing different skin tones. But this phone boasts one of the largest display sizes on the market: 6.4 inches.

Senapathy was diagnosed with carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes in 2017 and fibromyalgia in 2019. She has had to create a curated ergonomic workplace setup, otherwise her wrists and hands get weak and tingly, and she’s had to adjust how she holds her phone to prevent pain flares.

Recently, Senapathy underwent an electromyography, or an EMG, in which doctors insert electrodes into muscles to measure their electrical activity. The electrical response of the muscles tells doctors whether the nerve cells and muscles are successfully communicating. Depending on her results, steroid shots and even surgery might be required. Senapathy wants to stick with her Pixel 6, but the pain she’s experiencing may push her to buy a smaller phone. Unfortunately, options for these modestly sized phones are more limited.

These devices are now an inextricable part of our lives. So where does the burden of responsibility lie? Is it with consumers like Senapathy to adjust body positioning, get ergonomic workstations, and change habits to abate tech-related pain? Or should tech companies be held accountable for creating addictive devices that lead to musculoskeletal injury?

Kavin Senapathy, a freelance journalist, bought the Google Pixel 6 because of its high-quality camera, but she’s had to adjust how she holds the oversized phone to prevent pain flares.

Kavin Senapathy

A one-size-fits-all mentality for smartphones will continue to lead to injuries because every user has different wants and needs. S. Shyam Sundar, the founder of Penn State’s lab on media effects and a communications professor, says the needs for mobility and portability conflict with the desire for greater visibility. “The best thing a company can do is offer different sizes,” he says.

Joanna Bryson, an AI ethics expert and professor at The Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany, echoed these sentiments. “A lot of the lack of choice we see comes from the fact that the markets have consolidated so much,” she says. “We want to make sure there’s sufficient diversity [of products].”

Consumers can still maintain some control despite the ubiquity of tech. Sloan, the orthopedic surgeon, has to pester her son to change his body positioning when using his tablet. Our heads get heavier as they bend forward: at rest, they weigh 12 pounds, but bent 60 degrees, they weigh 60. “I have to tell him, ‘Raise your head, son!’” she says. It’s important, Sloan explains, to consider that growth and development will affect ligaments and bones in the neck, potentially making kids even more vulnerable to injuries from misusing gadgets. She recommends that parents limit their kids’ tech time to alleviate strain. She also suggested that tech companies implement a timer to remind us to change our body positioning.

In 2017, Nan-Wei Gong, a former contractor for Google, founded Figur8, which uses wearable trackers to measure muscle function and joint movement. It’s like physical therapy with biofeedback. “Each unique injury has a different biomarker,” says Gong. “With Figur8, you are comparing yourself to yourself.” This allows an individual to self-monitor for wear and tear and strengthen an injury in a way that’s efficient and designed for their body. Gong noticed that the work-from-home model during the COVID-19 pandemic created a new set of ergonomic problems that resulted in injuries. Figur8 provides real-time data for these injuries because “behavioral change requires feedback.”

Gong worked on a project called Jacquard while at Google. Textile experts weave conductive thread into their fabric, and the result is a patch of the fabric—like the cuff of a Levi’s jacket—that responds to commands on your smartphone. One swipe can call your partner or check the weather. It was designed with cyclists in mind who can’t easily check their phones, and it’s part of a growing movement in the tech industry to deliver creative, hands-free design. Gong thinks that engineers at large corporations like Google have accessibility in mind; it’s part of what drives their decisions for new products.

Display sizes of iPhones have become larger over time.

Sourced from Screenrant https://screenrant.com/iphone-apple-release-chronological-order-smartphone/ and Apple Tech Specs: https://www.apple.com/iphone-se/specs/

Back in Germany, Joanna Bryson reminds us that products like smartphones should adhere to best practices. These rules may be especially important for phones and other products with AI that are addictive. Disclosure, accountability, and regulation are important for AI, she says. “The correct balance will keep changing. But we have responsibilities and obligations to each other.” She was on an AI Ethics Council at Google, but the committee was disbanded after only one week due to issues with one of their members.

Bryson was upset about the Council’s dissolution but has faith that other regulatory bodies will prevail. OECD.AI, and international nonprofit, has drafted policies to regulate AI, which countries can sign and implement. “As of July 2021, 46 governments have adhered to the AI principles,” their website reads.

Sundar, the media effects professor, also directs Penn State’s Center for Socially Responsible AI. He says that inclusivity is a crucial aspect of social responsibility and how devices using AI are designed. “We have to go beyond first designing technologies and then making them accessible,” he says. “Instead, we should be considering the issues potentially faced by all different kinds of users before even designing them.”

Entomologist Jessica Ware is using new technologies to identify insect species in a changing climate. She shares her suggestions for how we can live harmoniously with creeper crawlers everywhere.

Jessica Ware is obsessed with bugs.

My guest today is a leading researcher on insects, the president of the Entomological Society of America and a curator at the American Museum of Natural History. Learn more about her here.

You may not think that insects and human health go hand-in-hand, but as Jessica makes clear, they’re closely related. A lot of people care about their health, and the health of other creatures on the planet, and the health of the planet itself, but researchers like Jessica are studying another thing we should be focusing on even more: how these seemingly separate areas are deeply entwined. (This is the theme of an upcoming event hosted by Leaps.org and the Aspen Institute.)

Listen to the Episode

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Entomologist Jessica Ware

D. Finnin / AMNH

Maybe it feels like a core human instinct to demonize bugs as gross. We seem to try to eradicate them in every way possible, whether that’s with poison, or getting out our blood thirst by stomping them whenever they creep and crawl into sight.

But where did our fear of bugs really come from? Jessica makes a compelling case that a lot of it is cultural, rather than in-born, and we should be following the lead of other cultures that have learned to live with and appreciate bugs.

The truth is that a healthy planet depends on insects. You may feel stung by that news if you hate bugs. Reality bites.

Jessica and I talk about whether learning to live with insects should include eating them and gene editing them so they don’t transmit viruses. She also tells me about her important research into using genomic tools to track bugs in the wild to figure out why and how we’ve lost 50 percent of the insect population since 1970 according to some estimates – bad news because the ecosystems that make up the planet heavily depend on insects. Jessica is leading the way to better understand what’s causing these declines in order to start reversing these trends to save the insects and to save ourselves.