Elizabeth Holmes Through the Director’s Lens

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Elizabeth Holmes.

"The Inventor," a chronicle of Theranos's storied downfall, premiered recently on HBO. Leapsmag reached out to director Alex Gibney, whom The New York Times has called "one of America's most successful and prolific documentary filmmakers," for his perspective on Elizabeth Holmes and the world she inhabited.

Do you think Elizabeth Holmes was a charismatic sociopath from the start — or is she someone who had good intentions, over-promised, and began the lies to keep her business afloat, a "fake it till you make it" entrepreneur like Thomas Edison?

I'm not qualified to say if EH was or is a sociopath. I don't think she started Theranos as a scam whose only purpose was to make money. If she had done so, she surely would have taken more money for herself along the way. I do think that she had good intentions and that she, as you say, "began the lies to keep her business afloat." ([Reporter John] Carreyrou's book points out that those lies began early.) I think that the Edison comparison is instructive for a lot of reasons.

First, Edison was the original "fake-it-till-you-make-it" entrepreneur. That puts this kind of behavior in the mainstream of American business. By saying that, I am NOT endorsing the ethic, just the opposite. As one Enron executive mused about the mendacity there, "Was it fraud or was it bad marketing?" That gives you a sense of how baked-in the "fake it" sensibility is.

"Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals."

I think EH shares one other thing with Edison, which is a huge ego coupled with a talent for storytelling as long as she is the heroic, larger-than-life main character. It's interesting that EH calls her initial device "Edison." Edison was the world's most famous "inventor," both because of the devices that came out of his shop and and for his ability for "self-invention." As Randall Stross notes in "The Wizard of Menlo Park," he was the first celebrity businessman. In addition to her "good intentions," EH was certainly motivated by fame and glory and many of her lies were in service to those goals.

Having a thirst for fame and a noble cause enabled her to think it was OK to lie in service of those goals. That doesn't excuse the lies. But those noble goals may have allowed EH to excuse them for herself or, more perniciously, to make believe that they weren't lies at all. This is where we get into scary psychological territory.

But rather than thinking of it as freakish, I think it's more productive to think of it as an exaggeration of the way we all lie to others and to ourselves. That's the point of including the Dan Ariely experiment with the dice. In that experiment, most of the subjects cheated more when they thought they were doing it for a good cause. Even more disturbing, that "good cause" allowed them to lie much more effectively because they had come to believe they weren't doing anything wrong. As it turns out, economics isn't a rational practice; it's the practice of rationalizing.

Where EH and Edison differ is that Edison had a firm grip on reality. He knew he could find a way to make the incandescent lightbulb work. There is no evidence that EH was close to making her "Edison" work. But rather than face reality (and possibly adjust her goals) she pretended that her dream was real. That kind of "over-promising" or "bold vision" is one thing when you are making a prototype in the lab. It's a far more serious matter when you are using a deeply flawed system on real patients. EH can tell herself that she had to do that (Walgreens was ready to walk away if she hadn't "gone live") or else Theranos would have run out of money.

But look at the calculation she made: she thought it was worth putting lives at risk in order to make her dream come true. Now we're getting into the realm of the sociopath. But my experience leads me to believe that -- as in the case of the Milgram experiment -- most people don't do terrible things right away, they come to crimes gradually as they become more comfortable with bigger and bigger rationalizations. At Theranos, the more valuable the company became, the bigger grew the lies.

The two whistleblowers come across as courageous heroes, going up against the powerful and intimidating company. The contrast between their youth and lack of power and the old elite backers of Theronos is staggering, and yet justice triumphed. Were the whistleblowers hesitant or afraid to appear in the film, or were they eager to share their stories?

By the time I got to them, they were willing and eager to tell their stories, once I convinced them that I would honor their testimony. In the case of Erika and Tyler, they were nudged to participate by John Carreyrou, in whom they had enormous trust.

"It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box."

Why do you think so many elite veterans of politics and venture capitalism succumbed to Holmes' narrative in the first place, without checking into the details of its technology or financials?

The reasons are all in the film. First, Channing Robertson and many of the old men on her board were clearly charmed by her and maybe attracted to her. They may have rationalized their attraction by convincing themselves it was for a good cause! Second, as Dan Ariely tells us, we all respond to stories -- more than graphs and data -- because they stir us emotionally. EH was a great storyteller. Third, the story of her as a female inventor and entrepreneur in male-dominated Silicon Valley is a tale that they wanted to invest in.

There may have been other factors. EH was very clever about the way she put together an ensemble of credibility. How could Channing Robertson, George Shultz, Henry Kissinger and Jim Mattis all be wrong? And when Walgreens put the Wellness Centers in stores, investors like Rupert Murdoch assumed that Walgreens must have done its due diligence. But they hadn't!

It's simply crazy that no one demanded to see an objective demonstration of the magic box. But that blind faith, as it turns out, is more a part of capitalism than we have been taught.

Do you think that Roger Parloff deserves any blame for the glowing Fortune story on Theranos, since he appears in the film to blame himself? Or was he just one more victim of Theranos's fraud?

He put her on the cover of Fortune so he deserves some blame for the fraud. He still blames himself. That willingness to hold himself to account shows how seriously he takes the job of a journalist. Unlike Elizabeth, Roger has the honesty and moral integrity to admit that he made a mistake. He owned up to it and published a mea culpa. That said, Roger was also a victim because Elizabeth lied to him.

Do you think investors in Silicon Valley, with their FOMO attitudes and deep pockets, are vulnerable to making the same mistake again with a shiny new startup, or has this saga been a sober reminder to do their due diligence first?

Many of the mistakes made with Theranos were the same mistakes made with Enron. We must learn to recognize that we are, by nature, trusting souls. Knowing that should lead us to a guiding slogan: "trust but verify."

The irony of Holmes dancing to "I Can't Touch This" is almost too perfect. How did you find that footage?

It was leaked to us.

"Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of 'The Apprentice.'"

Holmes is facing up to 20 years in prison for federal fraud charges, but Vanity Fair recently reported that she is seeking redemption, taking meetings with filmmakers for a possible documentary to share her "real" story. What do you think will become of Holmes in the long run?

It's usually a mistake to handicap a trial. My guess is that she will be convicted and do some prison time. But maybe she can convince jurors -- the way she convinced journalists, her board, and her investors -- that, on account of her noble intentions, she deserves to be found not guilty. "Somewhere, over the rainbow…"

After the trial, and possibly prison, I'm sure that EH will use her supporters (like Tim Draper) to find a way to use the virtual currency of her celebrity to rebrand herself and launch something new. Fitzgerald famously said that "there are no second acts in American lives." That may be the stupidest thing he ever said.

Donald Trump failed at virtually every business he ever embarked on. But he became a celebrity for being a fake businessman and used that celebrity -- and phony expertise -- to become president of the United States. Elizabeth Holmes is now famous for her fraud. Who better to host the re-boot of "The Apprentice." And then?

"You Can't Touch This!"

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

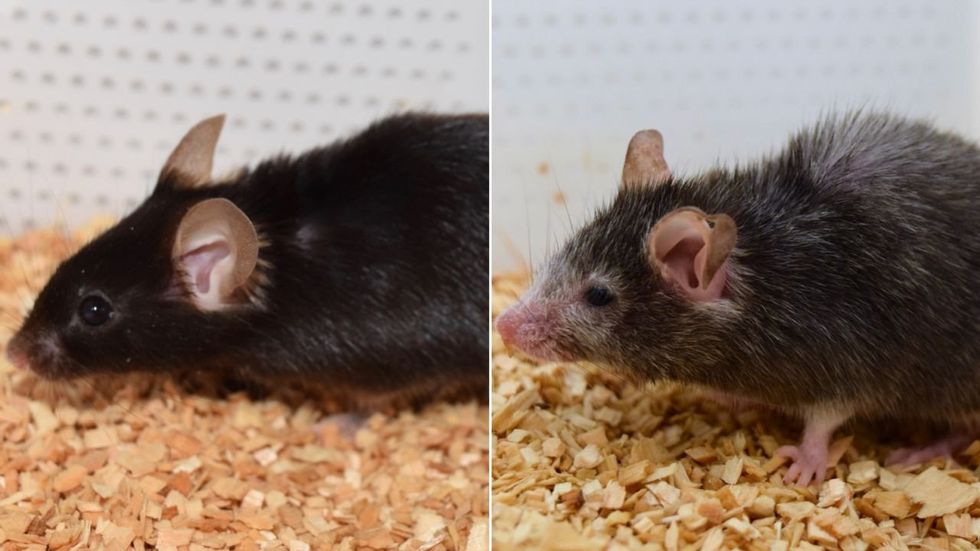

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School