The science of slowing down aging - even if you're not a tech billionaire

Chris Mirabile sprints on a track in Sarasota, Florida, during his daily morning workout. He claims to be a superager already, at age 38, with test results to back it up.

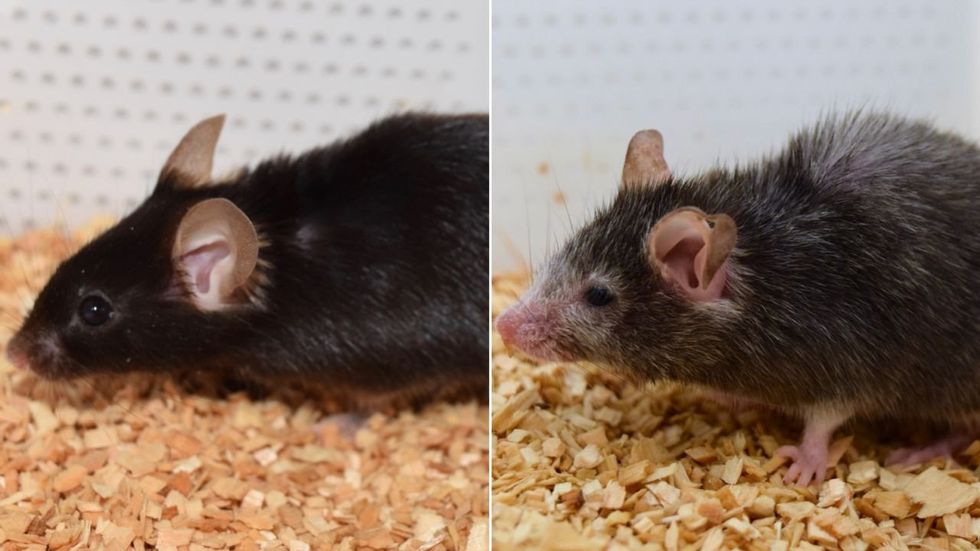

Earlier this year, Harvard scientists reported that they used an anti-aging therapy to reverse blindness in elderly mice. Several other studies in the past decade have suggested that the aging process can be modified, at least in lab organisms. Considering mice and humans share virtually the same genetic makeup, what does the rodent-based study mean for the humans?

In truth, we don’t know. Maybe nothing.

What we do know, however, is that a growing number of people are dedicating themselves to defying the aging process, to turning back the clock – the biological clock, that is. Take Bryan Johnson, a man who is less mouse than human guinea pig. A very wealthy guinea pig.

The 45-year-old venture capitalist spends over $2 million per year reversing his biological clock. To do this, he employs a team of 30 medical doctors and other scientists. His goal is to eventually reset his biological clock to age 18, and “have all of his major organs — including his brain, liver, kidneys, teeth, skin, hair, penis and rectum — functioning as they were in his late teens,” according to a story earlier this year in the New York Post.

But his daily routine paints a picture that is far from appealing: for example, rigorously adhering to a sleep schedule of 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. and consuming more than 100 pills and precisely 1,977 calories daily. Considering all of Johnson’s sacrifices, one discovers a paradox:

To live forever, he must die a little every day until he reaches his goal - if he ever reaches his goal.

Less extreme examples seem more helpful for people interested in happy, healthy aging. Enter Chris Mirabile, a New Yorker who says on his website, SlowMyAge.com, that he successfully reversed his biological age by 13.6 years, from the chronological age of 37.2 to a biological age of 23.6. To put this achievement in perspective, Johnson, to date, has reversed his biological clock by 2.5 years.

Mirabile's habits and overall quest to turn back the clock trace back to a harrowing experience at age 16 during a school trip to Manhattan, when he woke up on the floor with his shirt soaked in blood.

Mirabile, who is now 38, supports his claim with blood tests that purport to measure biological age by assessing changes to a person’s epigenome, or the chemical marks that affect how genes are expressed. Mirabile’s tests have been run and verified independently by the same scientific lab that analyzes Johnson’s. (In an email to Leaps.org, the lab, TruDiagnostic, confirmed Mirabile’s claims about his test results.)

There is considerable uncertainty among scientists about the extent to which these tests can accurately measure biological age in individuals. Even so, Mirabile’s results are intriguing. They could reflect his smart lifestyle for healthy aging.

His habits and overall quest to turn back the clock trace back to a harrowing experience at age 16 during a school trip to Manhattan, when Mirabile woke up on the floor with his shirt soaked in blood. He’d severed his tongue after a seizure. He later learned it was caused by a tumor the size of a golf ball. As a result, “I found myself contemplating my life, what I had yet to experience, and mortality – a theme that stuck with me during my year of recovery and beyond,” Mirabile told me.

For the next 15 years, he researched health and biology, integrating his learnings into his lifestyle. Then, in his early 30s, he came across an article in the journal Cell, "The Hallmarks of Aging," that outlined nine mechanisms of the body that define the aging process. Although the paper says there are no known interventions to delay some of these mechanisms, others, such as inflammation, struck Mirabile as actionable. Reading the paper was his “moment of epiphany” when it came to the areas where he could assert control to maximize his longevity.

He also wanted “to create a resource that my family, friends, and community could benefit from in the short term,” he said. He turned this knowledge base into a company called NOVOS dedicated to extending lifespan.

His longevity advice is more accessible than Johnson’s multi-million dollar approach, as Mirabile spends a fraction of that amount. Mirabile takes one epigenetic test per year and has a gym membership at $45 per month. Unlike Johnson, who takes 100 pills per day, Mirabile takes 10, costing another $45 monthly, including a B-complex, fish oil, Vitamins D3 and K2, and two different multivitamin supplements.

Mirabile’s methods may be easier to apply in other ways as well, since they include activities that many people enjoy anyway. He’s passionate about outdoor activities, travels frequently, and has loving relationships with friends and family, including his girlfriend and collie.

Here are a few of daily routines that could, he thinks, contribute to his impressively young bio age:

After waking at 7:45 am, he immediately drinks 16 ounces of water, with 1/4 teaspoon of sodium and potassium to replenish electrolytes. He takes his morning vitamins, brushes and flosses his teeth, puts on a facial moisturizing sunblock and goes for a brisk, two-mile walk in the sun. At 8:30 am on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays he lift weights, focusing on strength and power, especially in large muscle groups.

Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays are intense cardio days. He runs 5-7 miles or bicycles for 60 minutes first thing in the morning at a brisk pace, listening to podcasts. Sunday morning cardio is more leisurely.

After working out each day, he’s back home at 9:20 am, where he makes black coffee, showers, then applies serum and moisturizing sunblock to his face. He works for about three hours on his laptop, then has a protein shake and fruit.

Mirabile is a dedicated intermittent faster, with a six hour eating window in between 18 hours fasts. At 3 pm, he has lunch. The Mediterranean lineup often features salmon, sardines, olive oil, pink Himalayan salt plus potassium salt for balance, and lots of dried herbs and spices. He almost always finishes with 1/3 to 1/2 bar of dark chocolate.

If you are what you eat, Mirabile is made of mostly plants and lean meats. He follows a Mediterranean diet full of vegetables, fruits, fatty fish and other meats full of protein and unsaturated fats. “These may cost more than a meal at an American fast-food joint, but then again, not by much,” he said. Each day, he spends $25 on all his meals combined.

At 6 pm, he takes the dog out for a two-mile walk, taking calls for work or from family members along the way. At 7 pm, he dines with his girlfriend. Like lunch, this meal is heavy on widely available ingredients, including fish, fresh garlic, and fermented food like kimchi. Mirabile finishes this meal with sweets, like coconut milk yogurt with cinnamon and clove, some stevia, a mix of fresh berries and cacao nibs.

If Mirabile's epigenetic tests are accurate, his young biological age could be thanks to his healthy lifestyle, or it could come from a stroke of luck if he inherited genes that protect against aging.

At 8 pm, he wraps up work duties and watches shows with his girlfriend, applies serum and moisturizer yet again, and then meditates with the lights off. This wind-down, he said, improves his sleep quality. Wearing a sleep mask and earplugs, he’s asleep by about 10:30.

“I’ve achieved stellar health outcomes, even after having had the physiological stressors of a brain tumor, without spending a fortune,” Mirabile said. “In fact, even during times when I wasn’t making much money as a startup founder with few savings, I still managed to live a very healthy, pro-longevity lifestyle on a modest budget.”

Mirabile said living a cleaner, healthier existence is a reality that many readers can achieve. It’s certainly true that many people live in food deserts and have limited time for exercise or no access to gyms, but James R. Doty, a clinical professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, thinks many can take more action to stack the odds that they’ll “be happy and live longer.” Many of his recommendations echo aspects of Mirabile’s lifestyle.

Each night, Doty said, it’s vital to get anywhere between 6-8 hours of good quality sleep. Those who sleep less than 6 hours per night are at an increased risk of developing a whole host of medical problems, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and stroke.

In addition, it’s critical to follow Mirabile’s prescription of exercise for about one hour each day, and intensity levels matter. Doty noted that, in 2017, researchers at Brigham Young University found that people who ran at a fast pace for 30-40 minutes five days per week were, on average, biologically younger by nine years, compared to those who subscribed to more moderate exercise programs, as well as those who rarely exercised.

When it comes to nutrition, one should consider fasting for 16 hours per day, Doty said. This is known as the 16/8 method, where one’s daily calories are consumed within an eight hour window, fasting for the remaining 16 hours, just like Mirabile. Intermittent fasting is associated with cellular repair and less inflammation, though it’s not for everyone, Doty added. Consult with a medical professional before trying a fasting regimen.

Finally, Doty advised to “avoid anger, avoid stress.” Easier said than done, but not impossible. “Between stimulus and response, there is a pause and within that pause lies your freedom,” Doty said. Mirabile’s daily meditation ritual could be key to lower stress for healthy aging. Research has linked regular, long-term meditation to having a lower epigenetic age, compared to control groups.

Many other factors could apply. Having a life purpose, as Mirabile does with his company, has also been associated with healthy aging and lower epigenetic age. Of course, Mirabile is just one person, so it’s hard to know how his experience will apply to others. If his tests are accurate, his young biological age could be thanks to his healthy lifestyle, or it could come from a stroke of luck if he inherited genes that protect against aging. Clearly, though, any such genes did not protect him from cancer at an early age.

The third and perhaps most likely explanation: Mirabile’s very young biological age results from a combination of these factors. Some research shows that genetics account for only 25 percent of longevity. That means environmental factors could be driving the other 75 percent, such as where you live, frequency of exercise, quality of nutrition and social support.

The middle-aged – even Brian Johnson – probably can’t ever be 18 again. But more modest goals are reasonable for many. Control what you can for a longer, healthier life.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School

Breakthrough therapies are breaking patients' banks. Key changes could improve access, experts say.

Single-treatment therapies are revolutionizing medicine. But insurers and patients wonder whether they can afford treatment and, if they can, whether the high costs are worthwhile.

CSL Behring’s new gene therapy for hemophilia, Hemgenix, costs $3.5 million for one treatment, but helps the body create substances that allow blood to clot. It appears to be a cure, eliminating the need for other treatments for many years at least.

Likewise, Novartis’s Kymriah mobilizes the body’s immune system to fight B-cell lymphoma, but at a cost $475,000. For patients who respond, it seems to offer years of life without the cancer progressing.

These single-treatment therapies are at the forefront of a new, bold era of medicine. Unfortunately, they also come with new, bold prices that leave insurers and patients wondering whether they can afford treatment and, if they can, whether the high costs are worthwhile.

“Most pharmaceutical leaders are there to improve and save people’s lives,” says Jeremy Levin, chairman and CEO of Ovid Therapeutics, and immediate past chairman of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. If the therapeutics they develop are too expensive for payers to authorize, patients aren’t helped.

“The right to receive care and the right of pharmaceuticals developers to profit should never be at odds,” Levin stresses. And yet, sometimes they are.

Leigh Turner, executive director of the bioethics program, University of California, Irvine, notes this same tension between drug developers that are “seeking to maximize profits by charging as much as the market will bear for cell and gene therapy products and other medical interventions, and payers trying to control costs while also attempting to provide access to medical products with promising safety and efficacy profiles.”

Why Payers Balk

Health insurers can become skittish around extremely high prices, yet these therapies often accompany significant overall savings. For perspective, the estimated annual treatment cost for hemophilia exceeds $300,000. With Hemgenix, payers would break even after about 12 years.

But, in 12 years, will the patient still have that insurer? Therein lies the rub. U.S. payers, are used to a “pay-as-you-go” model, in which the lifetime costs of therapies typically are shared by multiple payers over many years, as patients change jobs. Single treatment therapeutics eliminate that cost-sharing ability.

"As long as formularies are based on profits to middlemen…Americans’ healthcare costs will continue to skyrocket,” says Patricia Goldsmith, the CEO of CancerCare.

“There is a phenomenally complex, bureaucratic reimbursement system that has grown, layer upon layer, during several decades,” Levin says. As medicine has innovated, payment systems haven’t kept up.

Therefore, biopharma companies begin working with insurance companies and their pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which act on an insurer’s behalf to decide which drugs to cover and by how much, early in the drug approval process. Their goal is to make sophisticated new drugs available while still earning a return on their investment.

New Payment Models

Pay-for-performance is one increasingly popular strategy, Turner says. “These models typically link payments to evidence generation and clinically significant outcomes.”

A biotech company called bluebird bio, for example, offers value-based pricing for Zynteglo, a $2.8 million possible cure for the rare blood disorder known as beta thalassaemia. It generally eliminates patients’ need for blood transfusions. The company is so sure it works that it will refund 80 percent of the cost of the therapy if patients need blood transfusions related to that condition within five years of being treated with Zynteglo.

In his February 2023 State of the Union speech, President Biden proposed three pilot programs to reduce drug costs. One of them, the Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model calls on the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to establish outcomes-based agreements with manufacturers for certain cell and gene therapies.

A mortgage-style payment system is another, albeit rare, approach. Amortized payments spread the cost of treatments over decades, and let people change employers without losing their healthcare benefits.

Only about 14 percent of all drugs that enter clinical trials are approved by the FDA. Pharma companies, therefore, have an exigent need to earn a profit.

The new payment models that are being discussed aren’t solutions to high prices, says Bill Kramer, senior advisor for health policy at Purchaser Business Group on Health (PBGH), a nonprofit that seeks to lower health care costs. He points out that innovative pricing models, although well-intended, may distract from the real problem of high prices. They are attempts to “soften the blow. The best thing would be to charge a reasonable price to begin with,” he says.

Instead, he proposes making better use of research on cost and clinical effectiveness. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) conducts such research in the U.S., determining whether the benefits of specific drugs justify their proposed prices. ICER is an independent non-profit research institute. Its reports typically assess the degrees of improvement new therapies offer and suggest prices that would reflect that. “Publicizing that data is very important,” Kramer says. “Their results aren’t used to the extent they could and should be.” Pharmaceutical companies tend to price their therapies higher than ICER’s recommendations.

Drug Development Costs Soar

Drug developers have long pointed to the onerous costs of drug development as a reason for high prices.

A 2020 study found the average cost to bring a drug to market exceeded $1.1 billion, while other studies have estimated overall costs as high as $2.6 billion. The development timeframe is about 10 years. That’s because modern therapeutics target precise mechanisms to create better outcomes, but also have high failure rates. Only about 14 percent of all drugs that enter clinical trials are approved by the FDA. Pharma companies, therefore, have an exigent need to earn a profit.

Skewed Incentives Increase Costs

Pricing isn’t solely at the discretion of pharma companies, though. “What patients end up paying has much more to do with their PBMs than the actual price of the drug,” Patricia Goldsmith, CEO, CancerCare, says. Transparency is vital.

PBMs control patients’ access to therapies at three levels, through price negotiations, pricing tiers and pharmacy management.

When negotiating with drug manufacturers, Goldsmith says, “PBMs exchange a preferred spot on a formulary (the insurer’s or healthcare provider’s list of acceptable drugs) for cash-base rebates.” Unfortunately, 25 percent of the time, those rebates are not passed to insurers, according to the PBGH report.

Then, PBMs use pricing tiers to steer patients and physicians to certain drugs. For example, Kramer says, “Sometimes PBMs put a high-cost brand name drug in a preferred tier and a lower-cost competitor in a less preferred, higher-cost tier.” As the PBGH report elaborates, “(PBMs) are incentivized to include the highest-priced drugs…since both manufacturing rebates, as well as the administrative fees they charge…are calculated as a percentage of the drug’s price.

Finally, by steering patients to certain pharmacies, PBMs coordinate patients’ access to treatments, control patients’ out-of-pocket costs and receive management fees from the pharmacies.

Therefore, Goldsmith says, “As long as formularies are based on profits to middlemen…Americans’ healthcare costs will continue to skyrocket.”

Transparency into drug pricing will help curb costs, as will new payment strategies. What will make the most impact, however, may well be the development of a new reimbursement system designed to handle dramatic, breakthrough drugs. As Kramer says, “We need a better system to identify drugs that offer dramatic improvements in clinical care.”