The U.S. must fund more biotech innovation – or other countries will catch up faster than you think

In the coming years, U.S. market share in biotech will decline unless the federal government makes investments to improve the quality and quantity of U.S. research, writes the author.

The U.S. has approximately 58 percent of the market share in the biotech sector, followed by China with 11 percent. However, this market share is the result of several years of previous research and development (R&D) – it is a present picture of what happened in the past. In the future, this market share will decline unless the federal government makes investments to improve the quality and quantity of U.S. research in biotech.

The effectiveness of current R&D can be evaluated in a variety of ways such as monies invested and the number of patents filed. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, the U.S. spends approximately 2.7 percent of GDP on R&D ($476,459.0M), whereas China spends 2 percent ($346,266.3M). However, investment levels do not necessarily translate into goods that end up contributing to innovation.

Patents are a better indication of innovation. The biotech industry relies on patents to protect their investments, making patenting a key tool in the process of translating scientific discoveries that can ultimately benefit patients. In 2020, China filed 1,497,159 patents, a 6.9 percent increase in growth rate. In contrast, the U.S. filed 597,172, a 3.9 percent decline. When it comes to patents filed, China has approximately 45 percent of the world share compared to 18 percent for the U.S.

So how did we get here? The nature of science in academia allows scientists to specialize by dedicating several years to advance discovery research and develop new inventions that can then be licensed by biotech companies. This makes academic science critical to innovation in the U.S. and abroad.

Academic scientists rely on government and foundation grants to pay for R&D, which includes salaries for faculty, investigators and trainees, as well as monies for infrastructure, support personnel and research supplies. Of particular interest to academic scientists to cover these costs is government support such as Research Project Grants, also known as R01 grants, the oldest grant mechanism from the National Institutes of Health. Unfortunately, this funding mechanism is extremely competitive, as applications have a success rate of only about 20 percent. To maximize the chances of getting funded, investigators tend to limit the innovation of their applications, since a project that seems overambitious is discouraged by grant reviewers.

Considering the difficulty in obtaining funding, the limited number of opportunities for scientists to become independent investigators capable of leading their own scientific projects, and the salaries available to pay for scientists with a doctoral degree, it is not surprising that the U.S. is progressively losing its workforce for innovation.

This approach affects the future success of the R&D enterprise in the U.S. Pursuing less innovative work tends to produce scientific results that are more obvious than groundbreaking, and when a discovery is obvious, it cannot be patented, resulting in fewer inventions that go on to benefit patients. Even though there are governmental funding options available for scientists in academia focused on more groundbreaking and translational projects, those options are less coveted by academic scientists who are trying to obtain tenure and long-term funding to cover salaries and other associated laboratory expenses. Therefore, since only a small percent of projects gets funded, the likelihood of scientists interested in pursuing academic science or even research in general keeps declining over time.

Efforts to raise the number of individuals who pursue a scientific education are paying off. However, the number of job openings for those trainees to carry out independent scientific research once they graduate has proved harder to increase. These limitations are not just in the number of faculty openings to pursue academic science, which are in part related to grant funding, but also the low salary available to pay those scientists after they obtain their doctoral degree, which ranges from $53,000 to $65,000, depending on years of experience.

Thus, considering the difficulty in obtaining funding, the limited number of opportunities for scientists to become independent investigators capable of leading their own scientific projects, and the salaries available to pay for scientists with a doctoral degree, it is not surprising that the U.S. is progressively losing its workforce for innovation, which results in fewer patents filed.

Perhaps instead of encouraging scientists to propose less innovative projects in order to increase their chances of getting grants, the U.S. government should give serious consideration to funding investigators for their potential for success -- or the success they have already achieved in contributing to the advancement of science. Such a funding approach should be tiered depending on career stage or years of experience, considering that 42 years old is the median age at which the first R01 is obtained. This suggests that after finishing their training, scientists spend 10 years before they establish themselves as independent academic investigators capable of having the appropriate funds to train the next generation of scientists who will help the U.S. maintain or even expand its market share in the biotech industry for years to come. Patenting should be given more weight as part of the academic endeavor for promotion purposes, or governmental investment in research funding should be increased to support more than just 20 percent of projects.

Remaining at the forefront of biotech innovation will give us the opportunity to not just generate more jobs, but it will also allow us to attract the brightest scientists from all over the world. This talented workforce will go on to train future U.S. scientists and will improve our standard of living by giving us the opportunity to produce the next generation of therapies intended to improve human health.

This problem cannot rely on just one solution, but what is certain is that unless there are more creative changes in funding approaches for scientists in academia, eventually we may be saying “remember when the U.S. was at the forefront of biotech innovation?”

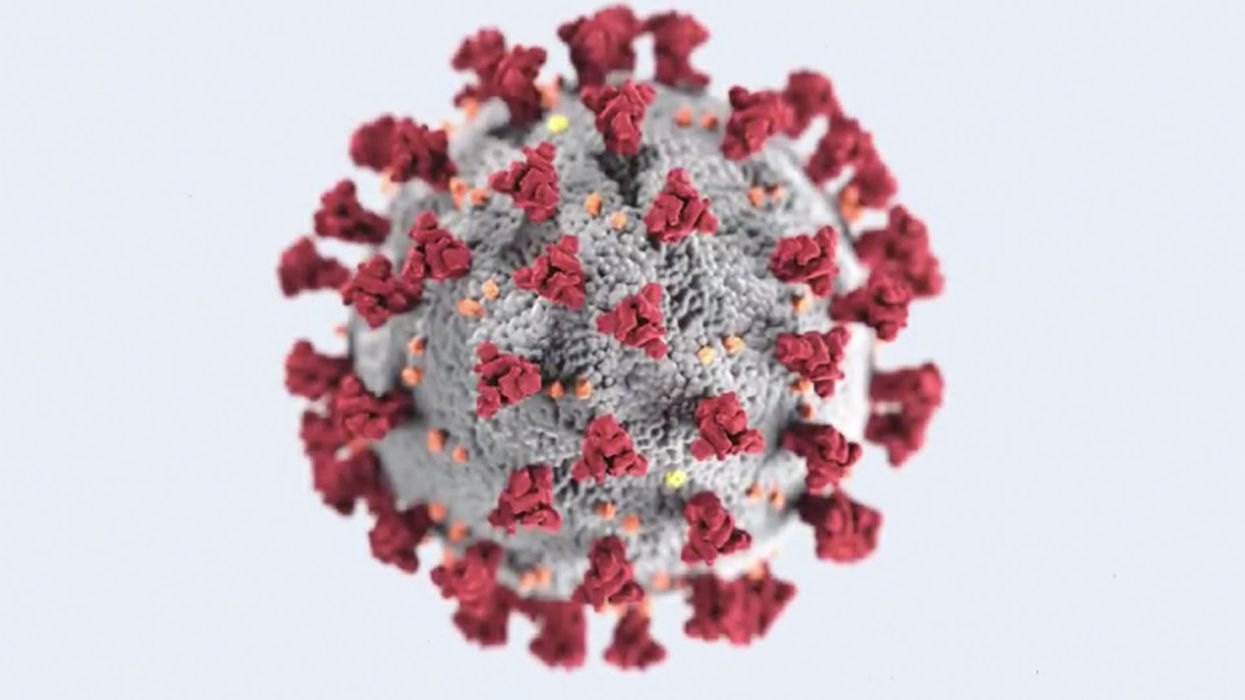

Blood Donated from Recovered Coronavirus Patients May Soon Yield a Stopgap Treatment

Antibodies from the blood of recovered patients is being tested as a stopgap treatment.

In October 1918, Lieutenant L.W. McGuire of the United States Navy sent a report to the American Journal of Public Health detailing a promising therapy that had already saved the lives of a number of officers suffering from pneumonia complications due to the Spanish influenza outbreak.

"These antibodies then become essentially drugs."

McGuire described how transfusions of blood from recovered patients – an idea which had first been trialed during a polio epidemic in 1916 – had led to rapid recovery in a series of severe pneumonia cases at a Naval Hospital in Massachusetts. "It is believed the serum has a decided influence in shortening the course of the disease, and lowering the mortality," he wrote.

Now more than a century on, this treatment – long forgotten in the western world - is once again coming to the fore during the current COVID-19 pandemic. With fatalities continuing to rise, and no vaccine expected for many months, experts are urging medical centers across the U.S. and Europe to initiate collaborations between critical care and transfusion services to offer this as an emergency treatment for those who need it most.

As of March 20, there are more than 90,000 individuals globally who have recovered from the disease. Some scientists believe that the blood of many of these people contains high levels of neutralizing antibodies that can kill the virus.

"These antibodies then become essentially drugs," said Arturo Casadevall, professor of Molecular Microbiology & Immunology at John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who is currently co-ordinating a clinical trial of convalescent serum for COVID-19 involving 20 institutions across the US.

"We're talking about preparing a therapy right out of the serum of those that have recovered. It could also be used in patients who are already sick, but have not progressed to respiratory failure, to treat them before they enter intensive care units. That will provide a lot of support because there's a limited number of respirators and resources."

The first conclusive data on how the blood of recovered patients can help tackle COVID-19 is set to come out of China, where it was also used as an emergency treatment during the SARS and MERS outbreaks. On February 9, a severely ill patient in Wuhan was treated with convalescent serum and since then, hospitals across China have used the therapy on a total of 245 patients, with 91 reportedly showing an improvement in symptoms.

In China alone, more than 58,000 patients have now recovered from COVID-19. Casadevall said that last week the country shipped 90 tons of serum and plasma from these patients to Italy – the center of the pandemic in Europe – for emergency use.

Some of the first people to be treated are likely to be doctors and nurses in hospitals who are most at risk of exposure.

A current challenge, however, is that the blood donation from the recovered patients must be precisely timed in order to maximize the number of antibodies a future patient receives. Doctors in China say that obtaining the necessary blood samples at the right time is one of the major barriers to applying the treatment on a larger scale.

"It's difficult to get the donations," said Dr. Yuan Shi of Chongqing Medical University. "When patients have recovered from the disease, we would like to collect their blood two to four weeks afterwards. We try our best to call back the patients, but it's sometimes difficult to get them to come back within that time period."

Because of such hurdles, Japan's largest drugmaker, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, is now working to turn neutralizing antibodies from recovered COVID-19 patients into a standardized drug product. They hope to launch a clinical trial for this in the next few months.

In the U.S., Casadevall hopes blood transfusions from recovered patients can become clinically available as a therapy within the next four weeks, once regulatory approval has been received. Some of the first people to be treated are likely to be doctors and nurses in hospitals who are most at risk of exposure, to provide a protective boost in their immunity.

"A lot of healthcare workers in the U.S. have already been asked to quarantine, and you can imagine what effect that's going to have on the healthcare system," he said. "It can't take large numbers of people staying home; there's not the capacity."

But not all medical experts are convinced it's the way to go, especially when it comes to the most severe cases of COVID-19. "There's no knowing whether that treatment would be useful or not," warned Dr. Andrew Freedman, head of Cardiff University's School of Medicine in the U.K.

"There are going to be better things available in a few months, but we are facing, 'What do you do now?'"

However, Casadevall says that the treatment is not envisioned as a panacea to treating coronavirus, but simply a temporary measure which could give doctors some options until stronger options such as vaccines or new drugs are available.

"This is a stopgap option," he said. "There are going to be better things available in a few months, but we are facing, 'What do you do now?' The only thing we can offer severely ill people at the moment is respiratory support and oxygen, and we don't have anything to prevent those exposed from going on and getting ill."

Social distancing is a critical part of the strategy to defeat the novel coronavirus.

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.