A skin patch to treat peanut allergies teaches the body to tolerate the nuts

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

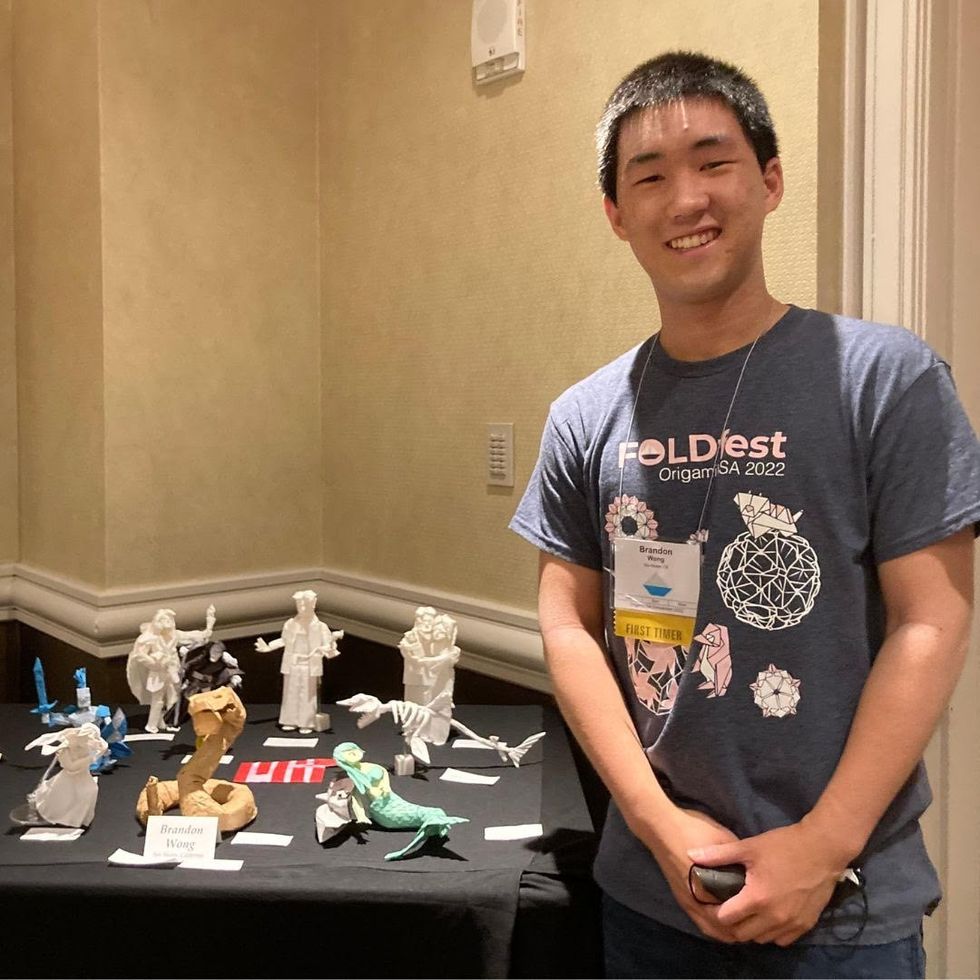

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”

Frequent, thorough handwashing is essential to protecting yourself from infection.

What's the case-fatality rate?

Currently, the official rate is 3.4%. But this is likely way too high. China was hit particularly hard, and their healthcare system was overwhelmed. The best data we have is from South Korea. The Koreans tested 210,000 people and detected the virus in 7,478 patients. So far, the death toll is 53, which is a case-fatality rate of 0.7%. This is seven times worse than the seasonal flu (which has a case-fatality rate of 0.1%).

What's the best way to clean your hands? Soap and water? Hand sanitizer?

Soap and water is always best. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly. (The CDC recommends 20 seconds.) If soap and water are not available, the CDC says to use hand sanitizer that is at least 60% alcohol. The problem with hand sanitizer, however, is that people neither use enough nor spread it over their hands properly. Also, the sanitizer should be covering your hands for 10-15 seconds, not evaporating before that.

How often should I wash my hands?

You should wash your hands after being in a public place, before you eat, and before you touch your face. It's a good idea to wash your hands after handling money and your cell phone, too.

How long can coronavirus live on surfaces?

It depends on the surface. According to the New York Times, "[C]old and flu viruses survive longer on inanimate surfaces that are nonporous, like metal, plastic and wood, and less on porous surfaces, like clothing, paper and tissue." According to the Journal of Hospital Infection, human coronaviruses "can persist on inanimate surfaces like metal, glass or plastic for up to 9 days, but can be efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62–71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 minute." (Note: Sodium hypochlorite is bleach.)

Can Lysol wipes kill it?

Maybe not. It depends on the active ingredient. Many Lysol products use benzalkonium chloride, which the aforementioned Journal of Hospital Infection paper said was "less effective." The EPA has released a list of disinfectants recommended for use against coronavirus.

Should you wear a mask in public?

The CDC does not recommend that healthy people wear a mask in public. The benefit is likely small. However, if you are sick, then you should wear a mask to help catch respiratory droplets as you exhale.

Will pets give it to you?

That can't be ruled out. There is a documented case of human-to-canine transmission. However, an article in LiveScience explains that canine-to-human is unlikely.

Are there any "normal" things we are doing that make things worse?

Yes! Not washing your hands!!

What does it mean that previously cleared people are getting sick again? Is it the virus within or have they caught it via contamination?

It's not entirely clear. It could be that the virus was never cleared to begin with. Or it could be that the person was simply infected again. That could happen if the antibodies generated don't last long.

Will the virus go away with the weather/summer?

Quite likely, yes. Cold and flu viruses don't do well outside in summer weather. (For influenza, the warm weather causes the viral envelope to become a liquid, and it can no longer protect the virus.) That's why cold and flu season is always during the late fall and winter. However, some experts think that it is a "false hope" that the coronavirus will disappear during the summer. We'll have to wait and see.

And will it come back in the fall/winter?

That's a likely outcome. Again, we'll have to wait and see. Some epidemiologists think that COVID-19 will become seasonal like influenza.

Does dry or humid air make a difference?

Flu viruses prefer cold, dry weather. That could be true of coronaviruses, too.

What is the incubation period?

According to the World Health Organization, it's about 5 days. But it could be anywhere from 1 to 14 days.

Should you worry about sitting next to asymptomatic people on a plane or train?

It's not possible to tell if an asymptomatic person is infected or not. That's what makes asymptomatic people tricky. Just be cautious. If you're worried, treat everyone like they might be infected. Don't let them get too close or cough in your face. Be sure to wash your hands.

Should you cancel air travel planned in the next 1-2 months in the U.S.?

There are no hard and fast rules. Use common sense. Avoid hotspots of infection. If you have a trip planned to Wuhan, you might want to wait on that one. If you have a trip planned to Seattle and you're over the age of 60 and/or have an underlying health condition, you may want to hold off on that, too. If you do fly on a plane, former FDA commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb recommends cleaning the back of your seat and other close contact areas with antiseptic wipes. He also refuses to take anything handed out by flight attendants, since he says the biggest route of transmission comes from touching contaminated surfaces (and then touching your face).

There have been reports of an escalation of hate crimes towards Asian Americans. Can the microbiologist help illuminate that this disease has impacted all racial groups?

People might be racist, but COVID-19 is not. It can infect anyone. Older people (i.e., 60 years and older) and those with underlying health conditions are most at risk. Interestingly, young people (aged 9 and under) are minimally impacted.

To what extent/if any should toddlers -- who put everything in mouth -- avoid group classes like Gymboree?

If they get infected, toddlers will probably experience only a mild illness. The problem is if the toddler then infects somebody at higher risk, like grandpa or grandma.

Should I avoid events like concerts or theater performances if I live in a place where there is known coronavirus?

It's not an unreasonable thing to do.

Any special advice or concerns for pregnant women?

There isn't good data on this. Previous evidence, reported by the CDC, suggests that pregnant women may be more susceptible to respiratory viruses.

Advice for residents of long-term care facilities/nursing homes?

Remind the nurse or aide to constantly wash their hands.

Can we eat at Chinese restaurants? Does eating onions kill viruses? Can I take an Uber and be safe from infection?

Yes. No. Does the Uber driver or previous passengers have coronavirus? It's not possible to tell. So, treat an Uber like a public space and behave accordingly.

What public spaces should we avoid?

That's hard to say. Some people avoid large gatherings, others avoid leaving the house. Ultimately, it's going to depend on who you are and what sort of risk you're willing to take. (For example, are you young and healthy or old and sick?) I would be willing to do things that I would advise older people avoid, like going to a sporting event.

What are the differences between the L strain and the S strain?

That's not entirely clear, and it's not even clear that they are separate strains. There are some genetic differences between them. However, just because RNA viruses mutate doesn't necessarily mean that the virus will mutate to something more dangerous or unrecognizable by our immune system. The measles virus mutates, but it more or less remains the same, which is why a single vaccine could eradicate it – if enough people actually were willing to get a measles shot.

Should I wear disposable gloves while traveling?

No. If you touch something that's contaminated, the virus will be on your glove instead of your hand. If you then touch your face, you still might get sick.

The Best Coronavirus Experts to Follow on Twitter

Following these experts on social media will help you stay well-informed about the coronavirus. Global virus and disease spread, coronavirus.

As the coronavirus tears across the globe, the world's anxiety is at a fever-pitch, and we're all craving information to stay on top of the crisis.

But turning to the Internet for credible updates isn't as simple as it sounds, since we have an invisible foe spreading as quickly as the virus itself: misinformation. From wild conspiracy theories to baseless rumors, an infodemic is in full swing.

For the latest official information, you should follow the CDC, WHO, and FDA, in addition to your local public health department. But it's also helpful to pay attention to the scientists, doctors, public health experts and journalists who are sharing their perspectives in real time as new developments unfold. Here's a handy guide to get you started:

VIROLOGY

Dr. Trevor Bedford/@trvrb: Scientist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center studying viruses, evolution and immunity.

Dr. Benhur Lee/@VirusWhisperer: Professor of microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

Dr. Angela Rasmussen/@angie_rasmussen: Virologist and associate research scientist at Columbia University

Dr. Florian Krammer/@florian_krammer: Professor of Microbiology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

EPIDEMIOLOGY:

Dr. Alice Sim/@alicesim: Infectious disease epidemiologist and consultant at the World Health Organization

Dr. Tara C. Smith/@aetiology: Infectious disease specialist and professor at Kent State University

Dr. Caitlin Rivers/@cmyeaton: Epidemiologist and assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Dr. Michael Mina/@michaelmina_lab: Physician and Assistant Professor of Epidemiology & Immunology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health

INFECTIOUS DISEASE:

Dr. Nahid Bhadelia/@BhadeliaMD: Infectious diseases physician and the medical director of Special Pathogens Unit at Boston University School of Medicine

Dr. Paul Sax/@PaulSaxMD: Clinical Director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital

Dr. Priya Sampathkumar/@PsampathkumarMD: Infectious Disease Specialist at the Mayo Clinic

Dr. Krutika Kuppalli/@KrutikaKuppalli: Medical doctor and Infectious Disease Specialist based in Palo Alto, CA

PANDEMIC PREP:

Dr. Syra Madad/@syramadad: Senior Director, System-wide Special Pathogens Program at New York City Health + Hospitals

Dr Sylvie Briand/@SCBriand: Director of Pandemic and Epidemic Diseases Department at the World Health Organization

Jeremy Konyndyk/@JeremyKonyndyk: Senior Policy Fellow at the Center for Global Development

Amesh Adalja/@AmeshAA: Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security

PUBLIC HEALTH:

Scott Becker/@scottjbecker: CEO of the Association of Public Health Laboratories

Dr. Scott Gottlieb/@ScottGottliebMD: Physician, former commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration

APHA Public Health Nursing/@APHAPHN: Public Health Nursing Section of the American Public Health Association

Dr. Tom Inglesby/@T_Inglesby: Director of the Johns Hopkins SPH Center for Health Security

Dr. Nancy Messonnier/@DrNancyM_CDC: Director of the Center for the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD)

Dr. Arthur Caplan/@ArthurCaplan: Professor of Bioethics at New York University Langone Medical Center

SCIENCE JOURNALISTS:

Laura Helmuth/@laurahelmuth: Incoming Editor in Chief of Scientific American

Helen Branswell/@HelenBranswell: Infectious disease and public health reporter at STAT

Sharon Begley/@sxbegle: Senior writer at STAT

Carolyn Johnson/@carolynyjohnson: Science reporter at the Washington Post

Amy Maxmen/@amymaxmen: Science writer and senior reporter at Nature

Laurie Garrett/@Laurie_Garrett: Pulitzer-prize winning science journalist, author of The Coming Plague, former senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations

Soumya Karlamangla/@skarlamangla: Health writer at the Los Angeles Times

André Picard/@picardonhealth: Health Columnist, The Globe and Mail

Caroline Chen/@CarolineYLChen: Healthcare reporter at ProPublica

Andrew Jacobs/@AndrewJacobsNYT: Science reporter at the New York Times

Meg Tirrell/@megtirrell: Biotech and pharma reporter for CNBC

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.