A skin patch to treat peanut allergies teaches the body to tolerate the nuts

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

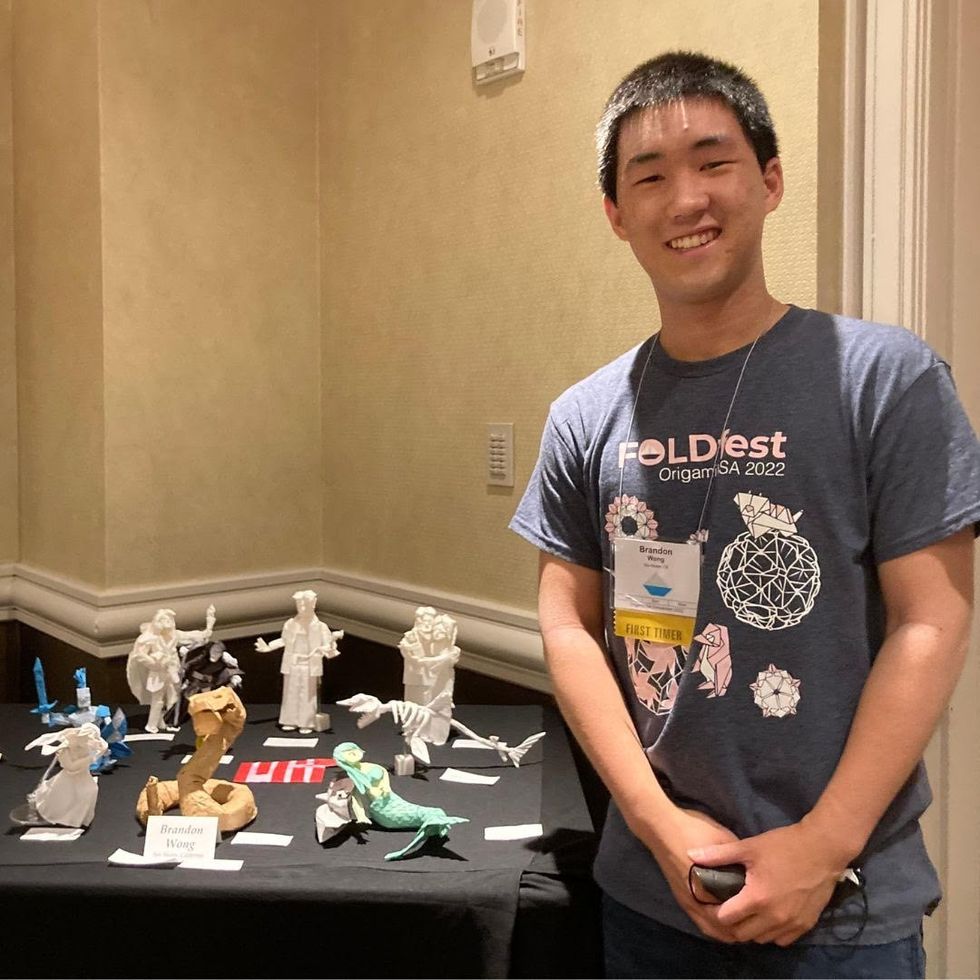

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”

How Leqembi became the biggest news in Alzheimer’s disease in 40 years, and what comes next

Betsy Groves, 73, with her granddaughter. Groves learned in 2021 that she has Alzheimer's disease. She hopes to take Leqembi, a drug approved by the FDA last week.

A few months ago, Betsy Groves traveled less than a mile from her home in Cambridge, Mass. to give a talk to a bunch of scientists. The scientists, who worked for the pharmaceutical companies Biogen and Eisai, wanted to know how she lived her life, how she thought about her future, and what it was like when a doctor’s appointment in 2021 gave her the worst possible news. Groves, 73, has Alzheimer’s disease. She caught it early, through a lumbar puncture that showed evidence of amyloid, an Alzheimer’s hallmark, in her cerebrospinal fluid. As a way of dealing with her diagnosis, she joined the Alzheimer’s Association’s National Early-Stage Advisory Board, which helped her shift into seeing her diagnosis as something she could use to help others.

After her talk, Groves stayed for lunch with the scientists, who were eager to put a face to their work. Biogen and Eisai were about to release the first drug to successfully combat Alzheimer’s in 40 years of experimental disaster. Their drug, which is known by the scientific name lecanemab and the marketing name Leqembi, was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration last Friday, Jan. 6, after a study in 1,800 people showed that it reduced cognitive decline by 27 percent over 18 months.

It is no exaggeration to say that this result is a huge deal. The field of Alzheimer’s drug development has been absolutely littered with failures. Almost everything researchers have tried has tanked in clinical trials. “Most of the things that we've done have proven not to be effective, and it's not because we haven’t been taking a ton of shots at goal,” says Anton Porsteinsson, director of the University of Rochester Alzheimer's Disease Care, Research, and Education Program, who worked on the lecanemab trial. “I think it's fair to say you don't survive in this field unless you're an eternal optimist.”

As far back as 1984, a cure looked like it was within reach: Scientists discovered that the sticky plaques that develop in the brains of those who have Alzheimer’s are made up of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid. Buildup of beta-amyloid seemed to be sufficient to disrupt communication between, and eventually kill, memory cells. If that was true, then the cure should be straightforward: Stop the buildup of beta-amyloid; stop the Alzheimer’s disease.

It wasn’t so simple. Over the next 38 years, hundreds of drugs designed either to interfere with the production of abnormal amyloid or to clear it from the brain flamed out in trials. It got so bad that neuroscience drug divisions at major pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers, GSK, Amgen) closed one by one, leaving the field to smaller, scrappier companies, like Cambridge-based Biogen and Tokyo-based Eisai. Some scientists began to dismiss the amyloid hypothesis altogether: If this protein fragment was so important to the disease, why didn’t ridding the brain of it do anything for patients? There was another abnormal protein that showed up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, called tau. Some researchers defected to the tau camp, or came to believe the proteins caused damage in combination.

The situation came to a head in 2021, when the FDA granted provisional approval to a drug called aducanumab, marketed as Aduhelm, against the advice of its own advisory council. The approval was based on proof that Aduhelm reduced beta-amyloid in the brain, even though one research trial showed it had no effect on people’s symptoms or daily life. Aduhelm could also cause serious side effects, like brain swelling and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (known as ARIA, these are basically micro-bleeds that appear on MRI scans). Without a clear benefit to memory loss that would make these risks worth it, Medicare refused to pay for Aduhelm among the general population. Two congressional committees launched an investigation into the drug’s approval, citing corporate greed, lapses in protocol, and an unjustifiably high price. (Aduhelm was also produced by the pharmaceutical company Biogen.)

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world.

So far, Leqembi is like Aduhelm in that it has been given accelerated approval only for its ability to remove amyloid from the brain. Both are monoclonal antibodies that direct the immune system to attack and clear dysfunctional beta-amyloid. The difference is that, while that’s all Aduhelm was ever shown to do, Leqembi’s makers have already asked the FDA to give it full approval – a decision that would increase the likelihood that Medicare will cover it – based on data that show it also improves Alzheimer’s sufferer’s lives. Leqembi targets a different type of amyloid, a soluble version called “protofibrils,” and that appears to change the effect. “It can give individuals and their families three, six months longer to be participating in daily life and living independently,” says Claire Sexton, PhD, senior director of scientific programs & outreach for the Alzheimer's Association. “These types of changes matter for individuals and for their families.”

To be clear, Leqembi is not the cure Alzheimer’s researchers hope for. It does not halt or reverse the disease, and people do not get better. While the drug is the first to show clear signs of a clinical benefit, the scientific establishment is split on how much of a difference Leqembi will make in the real world. It has “a rather small effect,” wrote NIH Alzheimer’s researcher Madhav Thambisetty, MD, PhD, in an email to Leaps.org. “It is unclear how meaningful this difference will be to patients, and it is unlikely that this level of difference will be obvious to a patient (or their caregivers).” Another issue is cost: Leqembi will become available to patients later this month, but Eisai is setting the price at $26,500 per year, meaning that very few patients will be able to afford it unless Medicare chooses to reimburse them for it.

The same side effects that plagued Aduhelm are common in Leqembi treatment as well. In many patients, amyloid doesn’t just accumulate around neurons, it also forms deposits in the walls of blood vessels. Blood vessels that are shot through with amyloid are more brittle. If you infuse a drug that targets amyloid, brittle blood vessels in the brain can develop leakage that results in swelling or bleeds. Most of these come with no symptoms, and are only seen during testing, which is why they are called “imaging abnormalities.” But in situations where patients have multiple diseases or are prescribed incompatible drugs, they can be serious enough to cause death. The three deaths reported from Leqembi treatment (so far) are enough to make Thambisetty wonder “how well the drug may be tolerated in real world clinical practice where patients are likely to be sicker and have multiple other medical conditions in contrast to carefully selected patients in clinical trials.”

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval.

Still, there are reasons to be excited. A successful Alzheimer’s drug can pave the way for combination studies, in which patients try a known effective drug alongside newer, more experimental ones; or preventative studies, which take place years before symptoms occur. It also represents enormous strides in researchers’ understanding of the disease. For example, drug dosages have increased massively—in some cases quadrupling—from the early days of Alzheimer’s research. And patient selection for studies has changed drastically as well. Doctors now know that you’ve got to catch the disease early, through PET-scans or CSF tests for amyloid, if you want any chance of changing its course.

Porsteinsson believes that earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease will be the next great advance in treatment, a more important step forward than Leqembi’s approval. His lab already uses blood tests for different types of amyloid, for different types of tau, and for measures of neuroinflammation, neural damage, and synaptic health, but commercially available versions from companies like C2N, Quest, and Fuji Rebio are likely to hit the market in the next couple of years. “[They are] going to transform the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease,” Porsteinsson says. “If someone is experiencing memory problems, their physicians will be able to order a blood test that will tell us if this is the result of changes in your brain due to Alzheimer's disease. It will ultimately make it much easier to identify people at a very early stage of the disease, where they are most likely to benefit from treatment.”

Learn more about new blood tests to detect Alzheimer's

Early detection can help patients for more philosophical reasons as well. Betsy Groves credits finding her Alzheimer’s early with giving her the space to understand and process the changes that were happening to her before they got so bad that she couldn’t. She has been able to update her legal documents and, through her role on the Advisory Group, help the Alzheimer’s Association with developing its programs and support services for people in the early stages of the disease. She still drives, and because she and her husband love to travel, they are hoping to get out of grey, rainy Cambridge and off to Texas or Arizona this spring.

Because her Alzheimer’s disease involves amyloid deposits (a “substantial portion” do not, says Claire Sexton, which is an additional complication for research), and has not yet reached an advanced stage, Groves may be a good candidate to try Leqembi. She says she’d welcome the opportunity to take it. If she can get access, Groves hopes the drug will give her more days to be fully functioning with her husband, daughters, and three grandchildren. Mostly, she avoids thinking about what the latter stages of Alzheimer’s might be like, but she knows the time will come when it will be her reality. “So whatever lecanemab can do to extend my more productive ways of engaging with relationships in the world,” she says. “I'll take that in a minute.”

How to have a good life, based on the world's longest study of happiness

In 1938, Harvard began an in-depth study of the secrets to happiness. It's still going, and in today's podcast episode, the study's director, Bob Waldinger, tells Leaps.org about the keys to a satisfying life, based on 85 years of research.

What makes for a good life? Such a simple question, yet we don't have great answers. Most of us try to figure it out as we go along, and many end up feeling like they never got to the bottom of it.

Shouldn't something so important be approached with more scientific rigor? In 1938, Harvard researchers began a study to fill this gap. Since then, they’ve followed hundreds of people over the course of their lives, hoping to identify which factors are key to long-term satisfaction.

Eighty-five years later, the Harvard Study of Adult Development is still going. And today, its directors, the psychiatrists Bob Waldinger and Marc Shulz, have published a book that pulls together the study’s most important findings. It’s called The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness.

In this podcast episode, I talked with Dr. Waldinger about life lessons that we can mine from the Harvard study and his new book.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

More background on the study

Back in the 1930s, the research began with 724 people. Some were first-year Harvard students paying full tuition, others were freshmen who needed financial help, and the rest were 14-year-old boys from inner city Boston – white males only. Fortunately, the study team realized the error of their ways and expanded their sample to include the wives and daughters of the first participants. And Waldinger’s book focuses on the Harvard study findings that can be corroborated by evidence from additional research on the lives of people of different races and other minorities.

The study now includes over 1,300 relatives of the original participants, spanning three generations. Every two years, the participants have sent the researchers a filled-out questionnaire, reporting how their lives are going. At five-year intervals, the research team takes a peek their health records and, every 15 years, the psychologists meet their subjects in-person to check out their appearance and behavior.

But they don’t stop there. No, the researchers factor in multiple blood samples, DNA, images from body scans, and even the donated brains of 25 participants.

Robert Waldinger, director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development.

Katherine Taylor

Dr. Waldinger is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, in addition to being Director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development. He got his M.D. from Harvard Medical School and has published numerous scientific papers he’s a practicing psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, he teaches Harvard medical students, and since that is clearly not enough to keep him busy, he’s also a Zen priest.

His book is a must-read if you’re looking for scientific evidence on how to design your life for more satisfaction so someday in the future you can look back on it without regret, and this episode was an amazing conversation in which Dr. Waldinger breaks down many of the cliches about the good life, making his advice real and tangible. We also get into what he calls “side-by-side” relationships, personality traits for the good life, and the downsides of being too strict about work-life balance.

Show links

- Bob Waldinger

- Waldinger's book, The Good Life: Lessons from the World's Longest Scientific Study of Happiness

- The Harvard Study of Adult Development

- Waldinger's Ted Talk

- Gallup report finding that people with good friends at work have higher engagement with their jobs

- The link between relationships and well-being

- Those with social connections live longer