Science Has Given Us the Power to Undermine Nature's Deadliest Creature: Should We Use It?

The Aedes aegypti mosquito, which can carry devastating diseases, was recently engineered by a biotech company to have a genetic "kill switch" intended to crash the local population in the Florida Keys.

Lurking among the swaying palm trees, sugary sands and azure waters of the Florida Keys is the most dangerous animal on earth: the mosquito.

While there are thousands of varieties of mosquitoes, only a small percentage of them are responsible for causing disease. One of the leading culprits is Aedes aegypti, which thrives in the warm standing waters of South Florida, Central America and other tropical climes, and carries the viruses that cause yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya and Zika.

Dengue, a leading cause of death in many Asian and Latin American countries, causes bleeding and pain so severe that it's referred to as "breakbone fever." Chikungunya and yellow fever can both be fatal, and Zika, when contracted by a pregnant woman, can infect her fetus and cause devastating birth defects, including a condition called microcephaly. Babies born with this condition have abnormally small heads and lack proper brain development, which leads to profound, lifelong disabilities.

Decades of efforts to eradicate the disease-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquito from the Keys and other tropical locales have had limited impact. Since the advent of pesticides, homes and neighborhoods have been drenched with them, but after each spraying, the mosquito population quickly bounces back, and the pesticides have to be sprayed over and over. But thanks to genetic engineering, new approaches are underway that could possibly prove safer, cheaper and more effective than any pesticide.

One of those approaches involves, ironically, releasing more mosquitoes in the Florida Keys.

The kill-switch will ensure that the female offspring die before they reach maturity and thus, be unable to reproduce.

British biotech company Oxitec has engineered male mosquitoes to have a genetic "kill-switch" that could potentially crash the local population of Aedes aegypti, at least in the short-term. The modified males that are being released are intended to mate with wild females.

Males don't bite; it's the female that's deadly, always seeking out blood to gorge on to help mature her eggs. After settling her filament-thin legs on her prey, she sinks a needlelike proboscis into the skin and sucks the blood until her translucent belly is bloated and glowing red.

The kill-switch will ensure that the female offspring die before they reach maturity and thus, be unable to reproduce. In some experiments using genetically modified mosquitoes, the small number of females that survived were rendered unable to bite. The modification prevented the proboscis, the sickle-like needle that pierces the skin, from forming properly. But this isn't the case with Oxitec's mosquitoes; in the Oxitec release, the females simply die off before they can mate.

The modified mosquitoes are the second genetically engineered insect to be released in the U.S. by Oxitec. The first was a modified diamondback moth, an agricultural pest that doesn't bite humans. But with the mosquitoes, there are many questions about the long-term effects on wild ecosystems, other species in the food chain, and human health. With the Keys initiative, there has been vociferous opposition from environmental groups and some local residents, but some scientists and public health experts say that genetically modified insects pose less of a risk than the diseases they carry and the powerful, indiscriminant pesticides used to combat them.

Oxitec spent a decade developing the technology and engaging in a massive public education campaign before beginning the field test in April. Eventually, the company will release 750,000 of the insects from six locations on three islands of the Florida Keys. Although the release has been approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, and the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District, the company was never able to obtain unanimous approval among local residents, some of whom worry that the experiment could cause irreversible damage to the ecosystem.

The company has already begun distributing multiple blue and white boxes containing the eggs of thousands of the mosquitoes which, when water is added, will hatch legions of modified males.

There are a number of techniques available to genetically engineer animals and plants to minimize disease and maximize crop yields. According to Kevin Gorman, chief development officer for Oxitec, the company's mosquitoes were altered by injecting genetic material into the eggs, testing them, then re-injecting them if not enough of the new genes were incorporated into the developing embryos. "We insert genes, but take nothing away," he says.

Gorman points out that the Oxitec mosquitoes will only pass the kill-switch genes on to some of their offspring, and that they will die out fairly quickly. They should temporarily lessen diseases by reducing the local population of Aedes aegypti, but to have a long-term effect, repeated introductions of the altered mosquitoes would have to take place.

Critics say the Oxitec experiment is a precursor to a far more consequential, and more troubling development: the introduction of gene drives in modified species that aggressively tilt inheritance factors in a decided direction.

Gene Drives

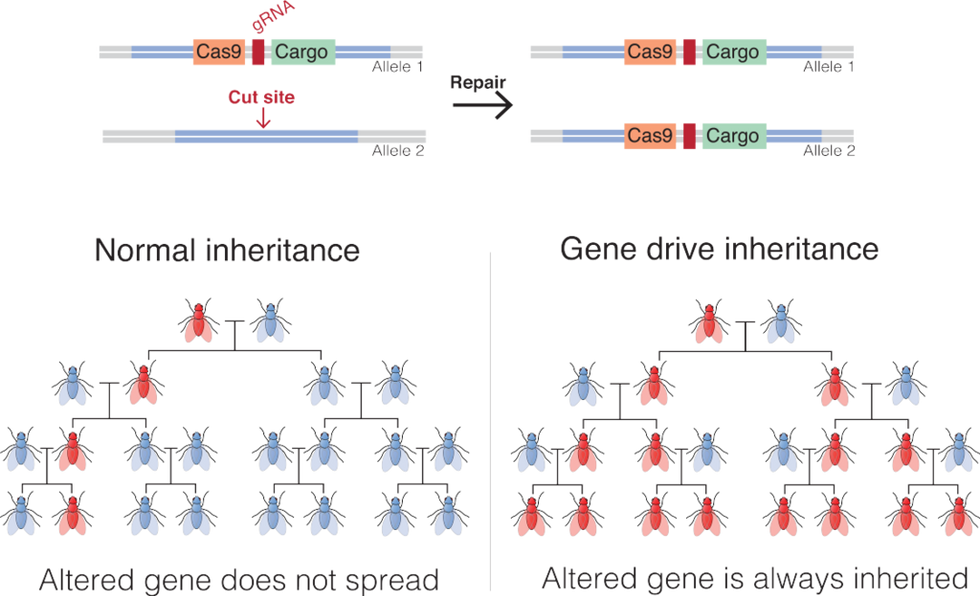

Gene drives coupled with the recent development of the gene-editing technique, CRISPR-Cas9, promise to be far more targeted and powerful than previous gene altering efforts. Gene drives override the normal laws of inheritance by harnessing natural processes involved in reproduction. The technique targets small sections of the animal's DNA and replaces it with an altered allele, or trait-determining snippet. Normally, when two members of a species mate, the offspring have a 50 percent chance of receiving an allele because they will receive one from each parent. But in a gene drive, each offspring ends up getting two copies of a desired allele from a single parent—the modified parent. The method "drives" the modified DNA into up to 100 percent of the animals' offspring.

In the case of gene drive mosquitoes, the modified males will mate with wild females. Upon fertilization of the egg, the offspring will start off with one copy of the targeted allele from each parent. But an enzyme, called Cas9, is introduced and acts as a kind of molecular scissors to cut, or damage, the "wild" allele. Then the developing embryo's genetic repair mechanisms kick in and, to repair the damage, copy the undamaged allele from the modified parent. In this way, the offspring ends up with two copies of the modified allele, and it will pass the modification on to virtually all of its progeny.

There is some debate among researchers and others about what constitutes a gene drive, but leaders in the nascent field, such as Andrea Crisanti, generally agree that the defining factor is the heritability of a change introduced into a species. A gene drive is not a particular gene or suite of genes, but a program that proliferates in a species because it is inherited by virtually all offspring.

An illustration of how gene drives spread an altered gene through a population.

Mariuswalter, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Of the experts who spoke with Leaps.org for this article, there was disagreement on whether the Oxitec mosquitoes carry a gene drive, but Gorman says they don't because they carry no inheritance advantage. The mosquitoes have baked-in limitations on their potential impact on the tropical ecosystem because the kill-switch should only temporarily affect the local population of Aedes aegypti. The modified mosquitoes will die pretty quickly. But modified organisms that do carry gene drives have the potential to spread widely and persist for an unknown period of time.

Since it has such a reproductive advantage, animals modified by CRISPR and carrying gene drives can quickly replace wild species that compete with them. On the other hand, if the gene drive carries a kill-switch, it can theoretically cause a whole species to collapse.

This makes many people uneasy in an age of mass extinctions, when animals and ecosystems are already under extreme stress due to climate change and the ceaseless destruction of their habitats. Ecosystems are intricate, delicately balanced mosaics where one animal's competitor is another animal's food. The interconnectedness of nature is only partially understood and still contains many mysteries as to what effects human intervention could eventually cause.

But there's a compelling case to be made for the use of gene drives in general. Economies throughout the world are often based on the ecosystem and its animals, which rely on a natural food chain that was evolved over billions of years. But diseases carried by mosquitoes and other animals cause massive damage, both economically and in terms of human suffering.

Malaria alone is a case in point. In 2019, the World Health Organization reported 229 million cases of malaria, which led to 449,000 deaths worldwide. Over 70 percent of those deaths were in children under the age of 12. Efforts to combat malaria-carrying mosquitoes rely on fogging the home with chemical pesticides and sleeping under pesticide-soaked nets, and while this has reduced the occurrence of malaria in recent years, the result is nowhere near as effective as eradicating the Anopheles gambiae mosquito that carries the disease.

Pesticides, a known carcinogen for animals and humans, are a blunt instrument, says Anthony Shelton, a biologist and entomologist at Cornell University. "There are no pesticides so specific that they just get the animal you want to target. They get pollinators. They get predators and parasites. They negatively affect the ecosystem, and they get into our bodies." And it's not uncommon for insects to develop resistance to pesticides, necessitating the continuous development of new, more powerful chemicals to control them.

"The harm of insecticides is not debatable," says Shelton. With gene drives, the potential harm is less clear.

Shelton also points out that although genetic modification sounds radical, people have been altering the genes of animals since before recorded history, through the selective breeding of farm and domesticated animals. While critics of genetic modification decry the possibility of changing the trajectory of evolution in animals, "We've been doing it for centuries," says Shelton. "Gene drives are just a much faster way to do what we've been doing all along."

Still, one might argue that farms are closed experiments, because animals enclosed within farms don't mate with wild animals. This limits the impact of human changes on the larger ecosystem. And getting new genes to work their way through multiple generations in longer-lived animals through breeding can take centuries, which imposes the element of time to ascertain the relative benefits of any introduced change. Gene drives fast-forward change in ways that have never been harnessed before.

The unique thing about gene drives, Shelton says, is that they only affect the targeted species, because those animals will only breed with their own species. Although the Oxitec mosquitoes are modified but not imbued with a gene drive, they illustrate the point. Aedes aegypti will only mate with its own species, and not with any of the other 3,000 varieties of mosquito. According to Shelton, "If they were to disappear, it would have no effect on the fish, bats and birds that feed on them." But should gene drives become widely used, this won't always be true of animals that play a larger part in the food chain. This will be especially true if gene drives are used in mammals.

One factor, cited by both proponents of gene drives and those who want a complete moratorium on them, is that once a gene drive is released into the wild, animals tend to evolve strategies to resist them. In a 2017 article in Nature, Philip Messer, a population geneticist at Cornell, says that gene drives create "the ideal conditions for resistant organisms to flourish."

Sometimes, when CRISPR is used and the Cas9 enzyme cuts an allele soon after egg fertilization, the animal's repair mechanism, rather than creating a straight copy of the desired allele, inserts random DNA letters. The gene drive won't recognize the new sequence, and the change will slip through. In this way, nature has a way of overriding gene drives.

In caged experiments using CRISPR-modified mosquitoes, while the gene drive initially worked, resistance has developed fairly rapidly. Scientists working for Target Malaria, the massive anti-malaria enterprise funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, are now working on developing a new version of a gene drive that is not so vulnerable to genetic resistance. But cage conditions are not representative of complex natural ecosystems, and to figure out how a modified species is going to affect the big picture, ultimately they will have to be tested in the wild.

Because there are so many unknowns, such testing is just too dangerous to undertake, according to environmentalists such as Dana Perls of the Friends of the Earth, an international consortium of environmental organizations headquartered in Amsterdam. "There's no safe way to experiment in the wild," she says. "Extinction is permanent, and to drive any species to extinction could have major environmental problems. At a time when we're seeing species disappearing at a high rate, we need to focus on safe processes and a slow approach rather than assume there's a silver bullet."

She cites a number of possible harmful outcomes from genetic modification, including the possible creation of dangerous hybrids that could be more effective at spreading disease and more resistant to pesticides. She points to a 2019 paper in Scientific Reports in which Yale researchers suggested there's evidence that genetically modified species can interbreed with organisms outside their own species. The researchers claimed that when Oxitec tested its modified Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Brazil, the release resulted in a dangerous hybrid due to the altered animals breeding with two other varieties of mosquito. They suggested that the hybrid mosquito was more robust than the original gene drive mosquitoes.

The paper contributed to breathless headlines in the media and made a big splash with the anti-GMO community. However, it turned out that when other scientists reviewed the data, they found it didn't support the authors' claims. In a short time, the editors of Nature ran an Editorial Expression of Concern for the article, noting that of the insects examined by the researchers, none of them contained the transgenes of the released mosquitoes. Among multiple concerns, Nature found that the researchers didn't follow the released population for more than a short time, and that previous work from the same authors had shown that after a short time, transgenes would have faded from the population.

Of course, unintended consequences are always a concern any time we interfere with nature, says Michael Montague, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins University's Center for Health Security. "Unpredictability is part of living in the world," he says. Still, he's relatively comfortable with the limited Florida Keys release.

"Even if one type of mosquito was eliminated in the Keys, the ecosystem wouldn't notice," he says. This is because of the thousands of other species of mosquito. He says that while the Keys initiative is ultimately a test, "Oxitec has done their due diligence."

Montague addressed another concern voiced by Perls. The Oxitec mosquitoes were developed so that the female larvae will only hatch in water containing the antibiotic tetracycline. Perls and others caution that, because of the widespread use of antibiotics, the drug inevitably makes its way into the water system, and could be present in the standing pools of water that mosquitoes mate and lay their eggs in.

It's highly unlikely that tetracycline would exist in concentrations high enough to make any difference, says Montague. "But even if it did happen, and the modified females hatched out and mated with wild males, many of their offspring would inherit the modification and only be able to hatch in tetracycline-laced water. The worst-case scenario would be that the pest control didn't work. Net effect: Zero," he says.

As for comparing GMO mosquitoes with insecticides, Montague says, "We 100 percent know insecticides have a harmful effect on human health, whereas modified [male] mosquitoes don't bite humans. They're essentially a chemical-free insecticide, and if there were to be some harmful effect on human health, it would have to be some complicated, convoluted effect" that no one has predicted.

It's not clear, though, given the transitory nature of self-limiting genetically modified insects, whether any effects on the ecosystem would be long-lasting. Certainly in the case of the Oxitec mosquitoes, any effect on the environment would likely be subtle. However, there are other species that are far more important to the food chain, and humans have been greatly impacting them for centuries, sometimes with disastrous effects.

The world's oceans are particularly vulnerable to the effects of human actions. "Codfish used to dominate the North Atlantic ecosystem," says Montague, but due to overfishing, there were huge changes to that ecosystem, including the expansion of their prey—lobsters, crabs and shrimp. The whole system got out of balance." The fish illustrate the international nature of the issues related to gene drives, because wild species have few boundaries and a change in one region can easily spread far and wide.

On the other hand, gene drives can be used for beneficial purposes beyond eliminating disease-carrying species. They could also be used to combat invasive species, fight crop-destroying insects, promote biodiversity, and give a leg up to endangered species that would otherwise die out.

Today nearly 90 percent of the world's islands have been invaded by disease-carrying rodents that have over-multiplied and are driving other island species to extinction. Common rodents such as rats and mice normally encounter a large number of predators in mainland territories, and this controls their numbers. Once they are introduced into island ecosystems, however, they have few predators and often become invasive. Because of this, they are a prevalent cause of the extinction of both animals and plants globally. The primary way to combat them has been to spread powerful toxicants that, when ingested, cause death. Not only has this inhumane practice had limited impact, the toxicants can be eaten by untargeted species and are toxic to humans.

The Genetic Biocontrol of Invasive Rodents program (GBIRd), an international consortium of scientists, ethicists, regulatory experts, sociologists, conservationists and others, is exploring the possible development of a genetically modified mouse that could be introduced to islands where rodents are invasive. Similar to the Oxitec mosquitoes, the mice would carry a modification that results in the appearance of only one sex, and they would also carry a gene drive. Theoretically, once they mate with the wild mice, all of the surviving offspring would be either male or female, and the species would disappear from the islands, giving other, threatened species an opportunity to revive.

GBIRd is moving slowly by design and is currently focused on asking if a genetically engineered mouse should be developed. The program is a potential model for how gene drives can be ethically developed with maximum foresight and the least impact on complex ecosystems. By first releasing a genetically engineered mouse on an island — likely years from now — the impact would naturally be contained within a limited locale.

Regulating GM Insects

While multiple agencies in the U.S. were involved in approving the release of the Oxitec mosquitoes, most experts agree that there is not a straightforward path to regulating genetically modified organisms released into the environment. Clearly, international regulation is needed as genetically modified organisms are released into open environments like the air and the ocean.

The United Nations' Convention on Biological Diversity, which oversees environmental issues at an international level, recently met to continue a process of hammering out voluntary protocols concerning gene drives. Multiple nations have already signed on to already-established protocols, but the United States has not and, according to Montague, is not expected to. "The U.S. will never be signatory to CBD agreements because agricultural companies are huge businesses" that may not see them as in their best interests, he says. Bans or limitations on the release of genetically modified organisms could limit crop yields, for example, thereby limiting profits.

Even if every nation signed on to international regulations of gene drives, cooperation is voluntary. The regulations wouldn't prevent bad actors from using the technology in nefarious ways, such as developing gene drives that can be used as weapons, according to Perls. An example would be unleashing a genetically modified invasive insect to destroy the crops of enemy nations. Or the releasing of a swarm of disease-carrying insects. But in this scenario, it would be very hard to limit the genetically modified species to a specific environment, and the bad actors could be unleashing disaster on themselves.

Because of the risks of misuse, scientists disagree on whether to openly share their gene drive research with others. But Montague believes that there should be a universal registry of gene drives, because "one gene drive can mess up another one. Two groups using the same species should know about each other," he says.

Ultimately, the decision of whether and when to release gene drives into nature rests with not one group, but with society as a whole. This includes not only diverse experts and regulatory bodies, but the general public, a group Oxitec spent considerable time and resources interacting with for their Florida Keys project. In the end, they gained approval for the initiative by a majority of Keys residents, but never gained a total consensus.

There's no escaping the fact that the use of gene drives is a nascent field, and even geneticists and regulators are still grapping with the best ways to develop, oversee, regulate, and control them. Much more data is needed to fully ascertain its risks and benefits.

Experts agree that the Oxitec venture isn't likely to have a noticeable effect on the larger ecosystem unless something truly catastrophic goes wrong. But following the GMO mosquitoes over time will give scientists more real-world data about the long-term effects of genetically altered species. If the release doesn't work, nothing about the ecosystem will change and Aedes aegypti will continue to be a menace to human health. But if something goes horribly wrong, it could hinder the field for years, if not forever.

On the other hand, if the Oxitec mosquitoes and other early initiatives achieve their goals of reducing disease, increasing crop yields, and protecting biodiversity, in the words of Anthony Shelton, "Maybe, 25 to 50 years from now, people will wonder what all the fuss was about."

Correction: The original version of this article mistakenly stated that the modified Oxitec mosquitoes would not be able to form a proper proboscis to bite humans. That is true for some modified mosquitoes but not the Oxitec ones, whose female offspring die off before they reach maturity. Additionally, the Oxitec release was not approved by the FDA and CDC, as originally stated. The FDA and CDC withdrew their role and passed the oversight to other regulatory entities.

Jamie Rettinger with his now fiance Amie Purnel-Davis, who helped him through the clinical trial.

Jamie Rettinger was still in his thirties when he first noticed a tiny streak of brown running through the thumbnail of his right hand. It slowly grew wider and the skin underneath began to deteriorate before he went to a local dermatologist in 2013. The doctor thought it was a wart and tried scooping it out, treating the affected area for three years before finally removing the nail bed and sending it off to a pathology lab for analysis.

"I have some bad news for you; what we removed was a five-millimeter melanoma, a cancerous tumor that often spreads," Jamie recalls being told on his return visit. "I'd never heard of cancer coming through a thumbnail," he says. None of his doctors had ever mentioned it either. "I just thought I was being treated for a wart." But nothing was healing and it continued to bleed.

A few months later a surgeon amputated the top half of his thumb. Lymph node biopsy tested negative for spread of the cancer and when the bandages finally came off, Jamie thought his medical issues were resolved.

Melanoma is the deadliest form of skin cancer. About 85,000 people are diagnosed with it each year in the U.S. and more than 8,000 die of the cancer when it spreads to other parts of the body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There are two peaks in diagnosis of melanoma; one is in younger women ages 30-40 and often is tied to past use of tanning beds; the second is older men 60+ and is related to outdoor activity from farming to sports. Light-skinned people have a twenty-times greater risk of melanoma than do people with dark skin.

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" --Diwakar Davar.

Jamie had a follow up PET scan about six months after his surgery. A suspicious spot on his lung led to a biopsy that came back positive for melanoma. The cancer had spread. Treatment with a monoclonal antibody (nivolumab/Opdivo®) didn't prove effective and he was referred to the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center in Pittsburgh, a four-hour drive from his home in western Ohio.

An alternative monoclonal antibody treatment brought on such bad side effects, diarrhea as often as 15 times a day, that it took more than a week of hospitalization to stabilize his condition. The only options left were experimental approaches in clinical trials.

Early research

"When I graduated from medical school, in 2005, melanoma was a death sentence" with a cure rate in the single digits, says Diwakar Davar, 39, an oncologist at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center who specializes in skin cancer. That began to change in 2010 with introduction of the first immunotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, to treat cancer. The antibodies attach to PD-1, a receptor on the surface of T cells of the immune system and on cancer cells. Antibody treatment boosted the melanoma cure rate to about 30 percent. The search was on to understand why some people responded to these drugs and others did not.

At the same time, there was a growing understanding of the role that bacteria in the gut, the gut microbiome, plays in helping to train and maintain the function of the body's various immune cells. Perhaps the bacteria also plays a role in shaping the immune response to cancer therapy.

One clue came from genetically identical mice. Animals ordered from different suppliers sometimes responded differently to the experiments being performed. That difference was traced to different compositions of their gut microbiome; transferring the microbiome from one animal to another in a process known as fecal transplant (FMT) could change their responses to disease or treatment.

When researchers looked at humans, they found that the patients who responded well to immunotherapies had a gut microbiome that looked like healthy normal folks, but patients who didn't respond had missing or reduced strains of bacteria.

Davar and his team knew that FMT had a very successful cure rate in treating the gut dysbiosis of Clostridioides difficile, a persistant intestinal infection, and they wondered if a fecal transplant from a patient who had responded well to cancer immunotherapy treatment might improve the cure rate of patients who did not originally respond to immunotherapies for melanoma.

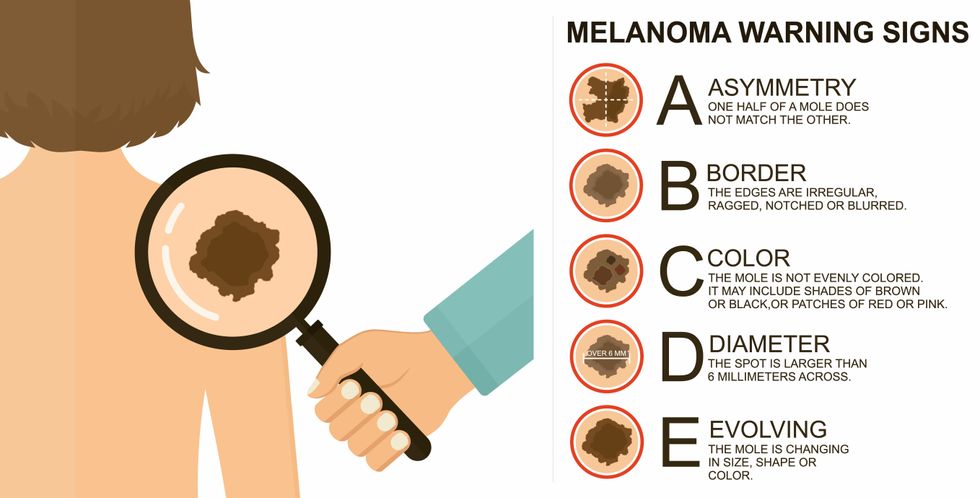

The ABCDE of melanoma detection

Adobe Stock

Clinical trial

"It was pretty weird, I was totally blasted away. Who had thought of this?" Jamie first thought when the hypothesis was explained to him. But Davar's explanation that the procedure might restore some of the beneficial bacterial his gut was lacking, convinced him to try. He quickly signed on in October 2018 to be the first person in the clinical trial.

Fecal donations go through the same safety procedures of screening for and inactivating diseases that are used in processing blood donations to make them safe for transfusion. The procedure itself uses a standard hollow colonoscope designed to screen for colon cancer and remove polyps. The transplant is inserted through the center of the flexible tube.

Most patients are sedated for procedures that use a colonoscope but Jamie doesn't respond to those drugs: "You can't knock me out. I was watching them on the TV going up my own butt. It was kind of unreal at that point," he says. "There were about twelve people in there watching because no one had seen this done before."

A test two weeks after the procedure showed that the FMT had engrafted and the once-missing bacteria were thriving in his gut. More importantly, his body was responding to another monoclonal antibody (pembrolizumab/Keytruda®) and signs of melanoma began to shrink. Every three months he made the four-hour drive from home to Pittsburgh for six rounds of treatment with the antibody drug.

"We were very, very lucky that the first patient had a great response," says Davar. "It allowed us to believe that even though we failed with the next six, we were on the right track. We just needed to tweak the [fecal] cocktail a little better" and enroll patients in the study who had less aggressive tumor growth and were likely to live long enough to complete the extensive rounds of therapy. Six of 15 patients responded positively in the pilot clinical trial that was published in the journal Science.

Davar believes they are beginning to understand the biological mechanisms of why some patients initially do not respond to immunotherapy but later can with a FMT. It is tied to the background level of inflammation produced by the interaction between the microbiome and the immune system. That paper is not yet published.

Surviving cancer

It has been almost a year since the last in his series of cancer treatments and Jamie has no measurable disease. He is cautiously optimistic that his cancer is not simply in remission but is gone for good. "I'm still scared every time I get my scans, because you don't know whether it is going to come back or not. And to realize that it is something that is totally out of my control."

"It was hard for me to regain trust" after being misdiagnosed and mistreated by several doctors he says. But his experience at Hillman helped to restore that trust "because they were interested in me, not just fixing the problem."

He is grateful for the support provided by family and friends over the last eight years. After a pause and a sigh, the ruggedly built 47-year-old says, "If everyone else was dead in my family, I probably wouldn't have been able to do it."

"I never hesitated to ask a question and I never hesitated to get a second opinion." But Jamie acknowledges the experience has made him more aware of the need for regular preventive medical care and a primary care physician. That person might have caught his melanoma at an earlier stage when it was easier to treat.

Davar continues to work on clinical studies to optimize this treatment approach. Perhaps down the road, screening the microbiome will be standard for melanoma and other cancers prior to using immunotherapies, and the FMT will be as simple as swallowing a handful of freeze-dried capsules off the shelf rather than through a colonoscopy. Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first oral fecal microbiota product for C. difficile, hopefully paving the way for more.

An older version of this hit article was first published on May 18, 2021

All organisms can repair damaged tissue, but none do it better than salamanders and newts. A surprising area of science could tell us how they manage this feat - and perhaps even help us develop a similar ability.

All organisms have the capacity to repair or regenerate tissue damage. None can do it better than salamanders or newts, which can regenerate an entire severed limb.

That feat has amazed and delighted man from the dawn of time and led to endless attempts to understand how it happens – and whether we can control it for our own purposes. An exciting new clue toward that understanding has come from a surprising source: research on the decline of cells, called cellular senescence.

Senescence is the last stage in the life of a cell. Whereas some cells simply break up or wither and die off, others transition into a zombie-like state where they can no longer divide. In this liminal phase, the cell still pumps out many different molecules that can affect its neighbors and cause low grade inflammation. Senescence is associated with many of the declining biological functions that characterize aging, such as inflammation and genomic instability.

Oddly enough, newts are one of the few species that do not accumulate senescent cells as they age, according to research over several years by Maximina Yun. A research group leader at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden and the Max Planck Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology and Genetics, in Dresden, Germany, Yun discovered that senescent cells were induced at some stages of regeneration of the salamander limb, “and then, as the regeneration progresses, they disappeared, they were eliminated by the immune system,” she says. “They were present at particular times and then they disappeared.”

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states.

Previous research on senescence in aging had suggested, logically enough, that applying those cells to the stump of a newly severed salamander limb would slow or even stop its regeneration. But Yun stood that idea on its head. She theorized that senescent cells might also play a role in newt limb regeneration, and she tested it by both adding and removing senescent cells from her animals. It turned out she was right, as the newt limbs grew back faster than normal when more senescent cells were included.

Senescent cells added to the edges of the wound helped the healthy muscle cells to “dedifferentiate,” essentially turning back the developmental clock of those cells into more primitive states, which could then be turned into progenitors, a cell type in between stem cells and specialized cells, needed to regrow the muscle tissue of the missing limb. “We think that this ability to dedifferentiate is intrinsically a big part of why salamanders can regenerate all these very complex structures, which other organisms cannot,” she explains.

Yun sees regeneration as a two part problem. First, the cells must be able to sense that their neighbors from the lost limb are not there anymore. Second, they need to be able to produce the intermediary progenitors for regeneration, , to form what is missing. “Molecularly, that must be encoded like a 3D map,” she says, otherwise the new tissue might grow back as a blob, or liver, or fin instead of a limb.

Wound healing

Another recent study, this time at the Mayo Clinic, provides evidence supporting the role of senescent cells in regeneration. Looking closely at molecules that send information between cells in the wound of a mouse, the researchers found that senescent cells appeared near the start of the healing process and then disappeared as healing progressed. In contrast, persistent senescent cells were the hallmark of a chronic wound that did not heal properly. The function and significance of senescence cells depended on both the timing and the context of their environment.

The paper suggests that senescent cells are not all the same. That has become clearer as researchers have been able to identify protein markers on the surface of some senescent cells. The patterns of these proteins differ for some senescent cells compared to others. In biology, such physical differences suggest functional differences, so it is becoming increasingly likely there are subsets of senescent cells with differing functions that have not yet been identified.

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes.

Scientists initially thought that senescent cells couldn’t play a role in regeneration because they could no longer reproduce, says Anthony Atala, a practicing surgeon and bioengineer who leads the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in North Carolina. But Yun’s study points in the other direction. “What this paper shows clearly is that these cells have the potential to be involved in tissue regeneration [in newts]. The question becomes, will these cells be able to do the same in humans.”

As our knowledge of senescent cells increases, Atala thinks we need to embrace a new analogy to help understand them: humans in retirement. They “have acquired a lot of wisdom throughout their whole life and they can help younger people and mentor them to grow to their full potential. We're seeing the same thing with these cells,” he says. They are no longer putting energy into their own reproduction, but the signaling molecules they secrete “can help other cells around them to regenerate.”

There are disagreements within the research community as to whether newts have acquired their regenerative capacity through a unique evolutionary change, or if other animals, including humans, retain this capacity buried somewhere in their genes. If so, it seems that our genes are unable to express this ability, perhaps as part of a tradeoff in acquiring other traits. It is a fertile area of research.

Dedifferentiation is likely to become an important process in the field of regenerative medicine. One extreme example: a lab has been able to turn back the clock and reprogram adult male skin cells into female eggs, a potential milestone in reproductive health. It will be more difficult to control just how far back one wishes to go in the cell's dedifferentiation – part way or all the way back into a stem cell – and then direct it down a different developmental pathway. Yun is optimistic we can learn these tricks from newts.

Senolytics

A growing field of research is using drugs called senolytics to remove senescent cells and slow or even reverse disease of aging.

“Senolytics are great, but senolytics target different types of senescence,” Yun says. “If senescent cells have positive effects in the context of regeneration, of wound healing, then maybe at the beginning of the regeneration process, you may not want to take them out for a little while.”

“If you look at pretty much all biological systems, too little or too much of something can be bad, you have to be in that central zone” and at the proper time, says Atala. “That's true for proteins, sugars, and the drugs that you take. I think the same thing is true for these cells. Why would they be different?”

Our growing understanding that senescence is not a single thing but a variety of things likely means that effective senolytic drugs will not resemble a single sledge hammer but more a carefully manipulated scalpel where some types of senescent cells are removed while others are added. Combinations and timing could be crucial, meaning the difference between regenerating healthy tissue, a scar, or worse.