Gene Editing of Embryos Is Both Ethical and Prudent

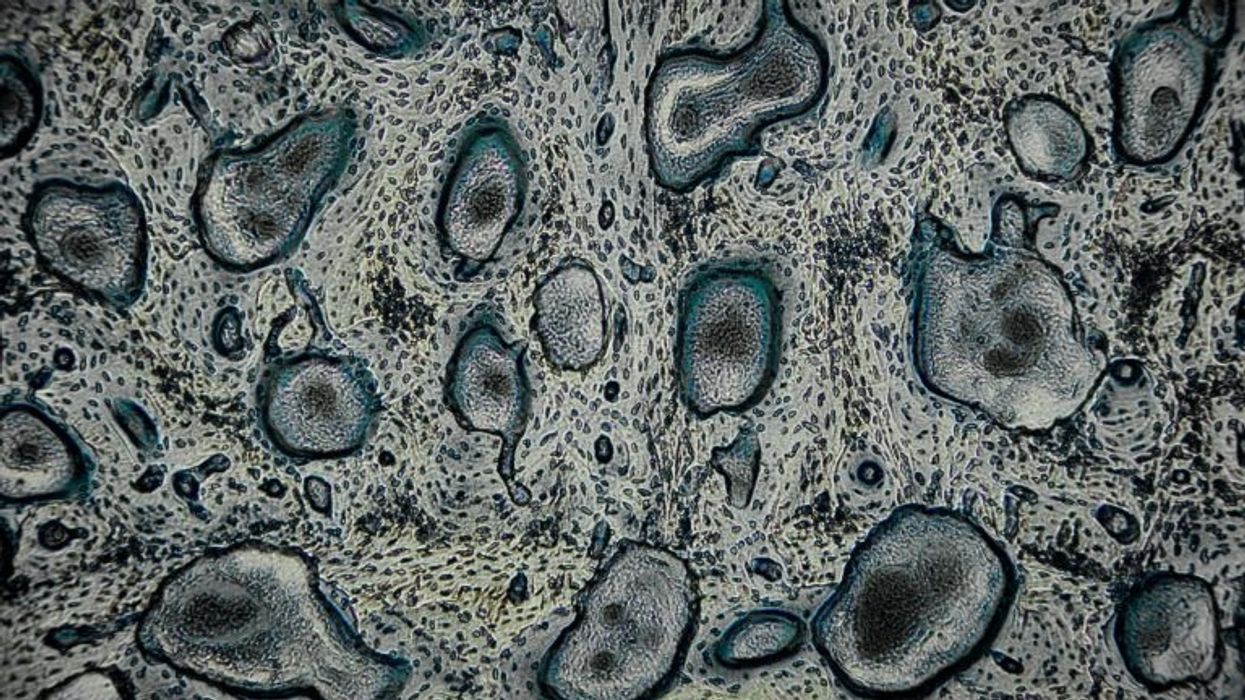

Human cells under a microscope

BIG QUESTION OF THE MONTH: Should we use CRISPR, the new technique that enables precise DNA editing, to change the genes of human embryos to eradicate disease--or even to enhance desirable traits? LeapsMag invited three leading experts to weigh in.

Now that researchers around the world have begun to edit the genes of human embryos with CRISPR, the ethical debate has become more timely than ever: Should this kind of research be on the table or categorically ruled out?

All of us need gene editing to be pursued, and if possible, made safe enough to use in humans. Not only to pave the way for effective procedures on adults, but more importantly, to keep open the possibility of using gene editing to protect embryos from susceptibility to major diseases and to prevent other debilitating genetic conditions from being passed on through them to future generations.

Objections to gene editing in embryos rest on three fallacious arguments:

- Gene editing is wrong because it affects future generations, the argument being that the human germline is sacred and inviolable.

- It constitutes an unknown and therefore unacceptable risk to future generations.

- The inability to obtain the consent of those future generations means we must not use gene editing.

We should be clear that there is no precautionary approach; just as justice delayed is justice denied, so therapy delayed is therapy denied.

Regarding the first point, many objections to germline interventions emphasize that such interventions are objectionable in that they affect "generations down the line". But this is true, not only of all assisted reproductive technologies, but of all reproduction of any kind.

Sexual reproduction would never have been licensed by regulators

As for the second point, every year an estimated 7.9 million children - 6% of total births worldwide - are born with a serious birth defect of genetic or partially genetic origin. Had sexual reproduction been invented by scientists rather than resulting from our evolved biology, it would never have been licensed by regulators - far too inefficient and dangerous!

If the appropriate benchmark for permissible risk of harm to future generations is sexual reproduction, other germline-changing techniques would need to demonstrate severe foreseeable dangers to fail.

Raising the third point in his statement on gene-editing in human embryos, Francis S. Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, stated: "The strong arguments against engaging in this activity remain … These include the serious and unquantifiable safety issues, ethical issues presented by altering the germline in a way that affects the next generation without their consent."

"Serious and unquantifiable" safety issues feature in all new technologies but consent is simply irrelevant for the simple and sufficient reason that there are no relevant people in existence capable of either giving or withholding consent to these sorts of changes in their own germline.

We all have to make decisions for future people without considering their inevitably absent consent. All would-be/might-be parents make numerous decisions about issues that might affect their future children. They do this all the time without thinking about consent of the children.

George Bernard Shaw and Isadora Duncan were possibly apocryphal exceptions. She, apparently, said to him something like: "Why don't we have a child? With my looks and your brains it cannot fail," and received Shaw's more rational assessment: "Yes, but what if it has my looks and your brains?"

If there is a discernible duty here, it is surely to try to create the best possible child, a child who will be the healthiest, most intelligent and most resilient to disease reasonably possible given the parents' other priorities. This is why we educate and vaccinate our children and give them a good diet if we can. That is what it is to act for the best, all things considered. This we have moral reasons to do; but they are not necessarily overriding reasons.

"There is no morally significant line between therapy and enhancement."

There is no morally significant line that can be drawn between therapy and enhancement. As I write these words in my London apartment, I am bathed in synthetic sunshine, one of the oldest and most amazing enhancement technologies. Before its invention, our ancestors had to rest or hide in the dark. With the advent of synthetic sunshine--firelight, candlelight, lamplight and electric light--we could work and play as long as we wished.Steven Hawking initially predicted that we might have about 7.6 billion years to go before the Earth gives up on us; he recently revised his position in relation to the Earth's continuing habitability as opposed to its physical survival: "We must also continue to go into space for the future of humanity," he said recently. "I don't think we will survive another thousand years without escaping beyond our fragile planet."

We will at some point have to escape both beyond our fragile planet and our fragile nature. One way to enhance our capacity to do both these things is by improving on human nature where we can do so in ways that are "safe enough." What we all have an inescapable moral duty to do is to continue with scientific investigation of gene editing techniques to the point at which we can make a rational choice. We must certainly not stop now.

At the end of a 2015 summit where I spoke about this issue, the renowned Harvard geneticist George Church noted that gene editing "opens up the possibility of not just transplantation from pigs to humans but the whole idea that a pig organ is perfectible…Gene editing could ensure the organs are very clean, available on demand and healthy, so they could be superior to human donor organs."

"We know for sure that in the future there will be no more human beings and no more planet Earth."

We know for sure that in the future there will be no more human beings and no more planet Earth. Either we will have been wiped out by our own foolishness or by brute forces of nature, or we will have further evolved by a process more rational and much quicker than Darwinian evolution--a process I described in my book Enhancing Evolution. Even more certain is that there will be no more planet Earth. Our sun will die, and with it, all possibility of life on this planet.As I say in my recent book How to Be Good:

By the time this happens, we may hope that our better evolved successors will have developed the science and the technology needed to survive and to enable us (them) to find and colonize another planet or perhaps even to build another planet; and in the meanwhile, to cope better with the problems presented by living on this planet.

Editor's Note: Check out the viewpoints expressing condemnation and mild curiosity.

Scientists experiment with burning iron as a fuel source

Sparklers produce a beautiful display of light and heat by burning metal dust, which contains iron. The recent work of Canadian and Dutch researchers suggests we can use iron as a cheap, carbon-free fuel.

Story by Freethink

Try burning an iron metal ingot and you’ll have to wait a long time — but grind it into a powder and it will readily burst into flames. That’s how sparklers work: metal dust burning in a beautiful display of light and heat. But could we burn iron for more than fun? Could this simple material become a cheap, clean, carbon-free fuel?

In new experiments — conducted on rockets, in microgravity — Canadian and Dutch researchers are looking at ways of boosting the efficiency of burning iron, with a view to turning this abundant material — the fourth most common in the Earth’s crust, about about 5% of its mass — into an alternative energy source.

Iron as a fuel

Iron is abundantly available and cheap. More importantly, the byproduct of burning iron is rust (iron oxide), a solid material that is easy to collect and recycle. Neither burning iron nor converting its oxide back produces any carbon in the process.

Iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again.

Iron has a high energy density: it requires almost the same volume as gasoline to produce the same amount of energy. However, iron has poor specific energy: it’s a lot heavier than gas to produce the same amount of energy. (Think of picking up a jug of gasoline, and then imagine trying to pick up a similar sized chunk of iron.) Therefore, its weight is prohibitive for many applications. Burning iron to run a car isn’t very practical if the iron fuel weighs as much as the car itself.

In its powdered form, however, iron offers more promise as a high-density energy carrier or storage system. Iron-burning furnaces could provide direct heat for industry, home heating, or to generate electricity.

Plus, iron oxide is potentially renewable by reacting with electricity or hydrogen to become iron again (as long as you’ve got a source of clean electricity or green hydrogen). When there’s excess electricity available from renewables like solar and wind, for example, rust could be converted back into iron powder, and then burned on demand to release that energy again.

However, these methods of recycling rust are very energy intensive and inefficient, currently, so improvements to the efficiency of burning iron itself may be crucial to making such a circular system viable.

The science of discrete burning

Powdered particles have a high surface area to volume ratio, which means it is easier to ignite them. This is true for metals as well.

Under the right circumstances, powdered iron can burn in a manner known as discrete burning. In its most ideal form, the flame completely consumes one particle before the heat radiating from it combusts other particles in its vicinity. By studying this process, researchers can better understand and model how iron combusts, allowing them to design better iron-burning furnaces.

Discrete burning is difficult to achieve on Earth. Perfect discrete burning requires a specific particle density and oxygen concentration. When the particles are too close and compacted, the fire jumps to neighboring particles before fully consuming a particle, resulting in a more chaotic and less controlled burn.

Presently, the rate at which powdered iron particles burn or how they release heat in different conditions is poorly understood. This hinders the development of technologies to efficiently utilize iron as a large-scale fuel.

Burning metal in microgravity

In April, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a suborbital “sounding” rocket, carrying three experimental setups. As the rocket traced its parabolic trajectory through the atmosphere, the experiments got a few minutes in free fall, simulating microgravity.

One of the experiments on this mission studied how iron powder burns in the absence of gravity.

In microgravity, particles float in a more uniformly distributed cloud. This allows researchers to model the flow of iron particles and how a flame propagates through a cloud of iron particles in different oxygen concentrations.

Existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

Insights into how flames propagate through iron powder under different conditions could help design much more efficient iron-burning furnaces.

Clean and carbon-free energy on Earth

Various businesses are looking at ways to incorporate iron fuels into their processes. In particular, it could serve as a cleaner way to supply industrial heat by burning iron to heat water.

For example, Dutch brewery Swinkels Family Brewers, in collaboration with the Eindhoven University of Technology, switched to iron fuel as the heat source to power its brewing process, accounting for 15 million glasses of beer annually. Dutch startup RIFT is running proof-of-concept iron fuel power plants in Helmond and Arnhem.

As researchers continue to improve the efficiency of burning iron, its applicability will extend to other use cases as well. But is the infrastructure in place for this transition?

Often, the transition to new energy sources is slowed by the need to create new infrastructure to utilize them. Fortunately, this isn’t the case with switching from fossil fuels to iron. Since the ideal temperature to burn iron is similar to that for hydrocarbons, existing fossil fuel power plants could potentially be retrofitted to run on iron fuel.

This article originally appeared on Freethink, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time.

How to Use Thoughts to Control Computers with Dr. Tom Oxley

Leaps.org talks with Dr. Tom Oxley, founding CEO of Synchron, a company that's taking a unique - and less invasive - approach to "brain-computer interfaces" for patients with ALS and other mobility challenges.

Tom Oxley is building what he calls a “natural highway into the brain” that lets people use their minds to control their phones and computers. The device, called the Stentrode, could improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of people living with spinal cord paralysis, ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases.

Leaps.org talked with Dr. Oxley for today’s podcast. A fascinating thing about the Stentrode is that it works very differently from other “brain computer interfaces” you may be familiar with, like Elon Musk’s Neuralink. Some BCIs are implanted by surgeons directly into a person’s brain, but the Stentrode is much less invasive. Dr. Oxley’s company, Synchron, opts for a “natural” approach, using stents in blood vessels to access the brain. This offers some major advantages to the handful of people who’ve already started to use the Stentrode.

The audio improves about 10 minutes into the episode. (There was a minor headset issue early on, but everything is audible throughout.) Dr. Oxley’s work creates game-changing opportunities for patients desperate for new options. His take on where we're headed with BCIs is must listening for anyone who cares about the future of health and technology.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

In our conversation, Dr. Oxley talks about “Bluetooth brain”; the critical role of AI in the present and future of BCIs; how BCIs compare to voice command technology; regulatory frameworks for revolutionary technologies; specific people with paralysis who’ve been able to regain some independence thanks to the Stentrode; what it means to be a neurointerventionist; how to scale BCIs for more people to use them; the risks of BCIs malfunctioning; organic implants; and how BCIs help us understand the brain, among other topics.

Dr. Oxley received his PhD in neuro engineering from the University of Melbourne in Australia. He is the founding CEO of Synchron and an associate professor and the head of the vascular bionics laboratory at the University of Melbourne. He’s also a clinical instructor in the Deepartment of Neurosurgery at Mount Sinai Hospital. Dr. Oxley has completed more than 1,600 endovascular neurosurgical procedures on patients, including people with aneurysms and strokes, and has authored over 100 peer reviewed articles.

Links:

Synchron website - https://synchron.com/

Assessment of Safety of a Fully Implanted Endovascular Brain-Computer Interface for Severe Paralysis in 4 Patients (paper co-authored by Tom Oxley) - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/art...

More research related to Synchron's work - https://synchron.com/research

Tom Oxley on LinkedIn - https://www.linkedin.com/in/tomoxl

Tom Oxley on Twitter - https://twitter.com/tomoxl?lang=en

Tom Oxley TED - https://www.ted.com/talks/tom_oxley_a_brain_implant_that_turns_your_thoughts_into_text?language=en

Tom Oxley website - https://tomoxl.com/

Novel brain implant helps paralyzed woman speak using digital avatar - https://engineering.berkeley.edu/news/2023/08/novel-brain-implant-helps-paralyzed-woman-speak-using-a-digital-avatar/

Edward Chang lab - https://changlab.ucsf.edu/

BCIs convert brain activity into text at 62 words per minute - https://med.stanford.edu/neurosurgery/news/2023/he...

Leaps.org: The Mind-Blowing Promise of Neural Implants - https://leaps.org/the-mind-blowing-promise-of-neural-implants/

Tom Oxley