Gene Editing of Embryos Is Both Ethical and Prudent

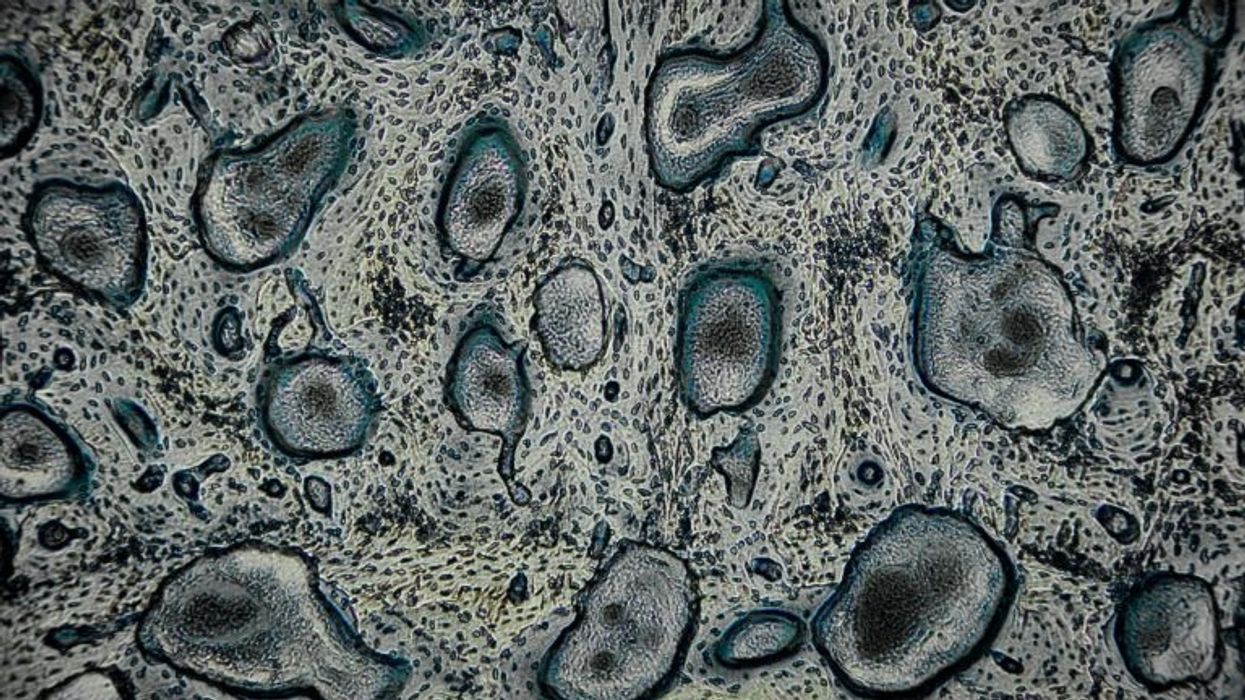

Human cells under a microscope

BIG QUESTION OF THE MONTH: Should we use CRISPR, the new technique that enables precise DNA editing, to change the genes of human embryos to eradicate disease--or even to enhance desirable traits? LeapsMag invited three leading experts to weigh in.

Now that researchers around the world have begun to edit the genes of human embryos with CRISPR, the ethical debate has become more timely than ever: Should this kind of research be on the table or categorically ruled out?

All of us need gene editing to be pursued, and if possible, made safe enough to use in humans. Not only to pave the way for effective procedures on adults, but more importantly, to keep open the possibility of using gene editing to protect embryos from susceptibility to major diseases and to prevent other debilitating genetic conditions from being passed on through them to future generations.

Objections to gene editing in embryos rest on three fallacious arguments:

- Gene editing is wrong because it affects future generations, the argument being that the human germline is sacred and inviolable.

- It constitutes an unknown and therefore unacceptable risk to future generations.

- The inability to obtain the consent of those future generations means we must not use gene editing.

We should be clear that there is no precautionary approach; just as justice delayed is justice denied, so therapy delayed is therapy denied.

Regarding the first point, many objections to germline interventions emphasize that such interventions are objectionable in that they affect "generations down the line". But this is true, not only of all assisted reproductive technologies, but of all reproduction of any kind.

Sexual reproduction would never have been licensed by regulators

As for the second point, every year an estimated 7.9 million children - 6% of total births worldwide - are born with a serious birth defect of genetic or partially genetic origin. Had sexual reproduction been invented by scientists rather than resulting from our evolved biology, it would never have been licensed by regulators - far too inefficient and dangerous!

If the appropriate benchmark for permissible risk of harm to future generations is sexual reproduction, other germline-changing techniques would need to demonstrate severe foreseeable dangers to fail.

Raising the third point in his statement on gene-editing in human embryos, Francis S. Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, stated: "The strong arguments against engaging in this activity remain … These include the serious and unquantifiable safety issues, ethical issues presented by altering the germline in a way that affects the next generation without their consent."

"Serious and unquantifiable" safety issues feature in all new technologies but consent is simply irrelevant for the simple and sufficient reason that there are no relevant people in existence capable of either giving or withholding consent to these sorts of changes in their own germline.

We all have to make decisions for future people without considering their inevitably absent consent. All would-be/might-be parents make numerous decisions about issues that might affect their future children. They do this all the time without thinking about consent of the children.

George Bernard Shaw and Isadora Duncan were possibly apocryphal exceptions. She, apparently, said to him something like: "Why don't we have a child? With my looks and your brains it cannot fail," and received Shaw's more rational assessment: "Yes, but what if it has my looks and your brains?"

If there is a discernible duty here, it is surely to try to create the best possible child, a child who will be the healthiest, most intelligent and most resilient to disease reasonably possible given the parents' other priorities. This is why we educate and vaccinate our children and give them a good diet if we can. That is what it is to act for the best, all things considered. This we have moral reasons to do; but they are not necessarily overriding reasons.

"There is no morally significant line between therapy and enhancement."

There is no morally significant line that can be drawn between therapy and enhancement. As I write these words in my London apartment, I am bathed in synthetic sunshine, one of the oldest and most amazing enhancement technologies. Before its invention, our ancestors had to rest or hide in the dark. With the advent of synthetic sunshine--firelight, candlelight, lamplight and electric light--we could work and play as long as we wished.Steven Hawking initially predicted that we might have about 7.6 billion years to go before the Earth gives up on us; he recently revised his position in relation to the Earth's continuing habitability as opposed to its physical survival: "We must also continue to go into space for the future of humanity," he said recently. "I don't think we will survive another thousand years without escaping beyond our fragile planet."

We will at some point have to escape both beyond our fragile planet and our fragile nature. One way to enhance our capacity to do both these things is by improving on human nature where we can do so in ways that are "safe enough." What we all have an inescapable moral duty to do is to continue with scientific investigation of gene editing techniques to the point at which we can make a rational choice. We must certainly not stop now.

At the end of a 2015 summit where I spoke about this issue, the renowned Harvard geneticist George Church noted that gene editing "opens up the possibility of not just transplantation from pigs to humans but the whole idea that a pig organ is perfectible…Gene editing could ensure the organs are very clean, available on demand and healthy, so they could be superior to human donor organs."

"We know for sure that in the future there will be no more human beings and no more planet Earth."

We know for sure that in the future there will be no more human beings and no more planet Earth. Either we will have been wiped out by our own foolishness or by brute forces of nature, or we will have further evolved by a process more rational and much quicker than Darwinian evolution--a process I described in my book Enhancing Evolution. Even more certain is that there will be no more planet Earth. Our sun will die, and with it, all possibility of life on this planet.As I say in my recent book How to Be Good:

By the time this happens, we may hope that our better evolved successors will have developed the science and the technology needed to survive and to enable us (them) to find and colonize another planet or perhaps even to build another planet; and in the meanwhile, to cope better with the problems presented by living on this planet.

Editor's Note: Check out the viewpoints expressing condemnation and mild curiosity.

A robot server, controlled remotely by a disabled worker, delivers drinks to patrons at the DAWN cafe in Tokyo.

A sleek, four-foot tall white robot glides across a cafe storefront in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district, holding a two-tiered serving tray full of tea sandwiches and pastries. The cafe’s patrons smile and say thanks as they take the tray—but it’s not the robot they’re thanking. Instead, the patrons are talking to the person controlling the robot—a restaurant employee who operates the avatar from the comfort of their home.

It’s a typical scene at DAWN, short for Diverse Avatar Working Network—a cafe that launched in Tokyo six years ago as an experimental pop-up and quickly became an overnight success. Today, the cafe is a permanent fixture in Nihonbashi, staffing roughly 60 remote workers who control the robots remotely and communicate to customers via a built-in microphone.

More than just a creative idea, however, DAWN is being hailed as a life-changing opportunity. The workers who control the robots remotely (known as “pilots”) all have disabilities that limit their ability to move around freely and travel outside their homes. Worldwide, an estimated 16 percent of the global population lives with a significant disability—and according to the World Health Organization, these disabilities give rise to other problems, such as exclusion from education, unemployment, and poverty.

These are all problems that Kentaro Yoshifuji, founder and CEO of Ory Laboratory, which supplies the robot servers at DAWN, is looking to correct. Yoshifuji, who was bedridden for several years in high school due to an undisclosed health problem, launched the company to help enable people who are house-bound or bedridden to more fully participate in society, as well as end the loneliness, isolation, and feelings of worthlessness that can sometimes go hand-in-hand with being disabled.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that [people with disabilities] feel they are a burden to society, or that they fear their families suffer by caring for them,” said Yoshifuji in an interview in 2020. “We are dedicating ourselves to providing workable, technology-based solutions. That is our purpose.”

Shota, Kuwahara, a DAWN employee with muscular dystrophy, agrees. "There are many difficulties in my daily life, but I believe my life has a purpose and is not being wasted," he says. "Being useful, able to help other people, even feeling needed by others, is so motivational."

A woman receives a mammogram, which can detect the presence of tumors in a patient's breast.

When a patient is diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer, having surgery to remove the tumor is considered the standard of care. But what happens when a patient can’t have surgery?

Whether it’s due to high blood pressure, advanced age, heart issues, or other reasons, some breast cancer patients don’t qualify for a lumpectomy—one of the most common treatment options for early-stage breast cancer. A lumpectomy surgically removes the tumor while keeping the patient’s breast intact, while a mastectomy removes the entire breast and nearby lymph nodes.

Fortunately, a new technique called cryoablation is now available for breast cancer patients who either aren’t candidates for surgery or don’t feel comfortable undergoing a surgical procedure. With cryoablation, doctors use an ultrasound or CT scan to locate any tumors inside the patient’s breast. They then insert small, needle-like probes into the patient's breast which create an “ice ball” that surrounds the tumor and kills the cancer cells.

Cryoablation has been used for decades to treat cancers of the kidneys and liver—but only in the past few years have doctors been able to use the procedure to treat breast cancer patients. And while clinical trials have shown that cryoablation works for tumors smaller than 1.5 centimeters, a recent clinical trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York has shown that it can work for larger tumors, too.

In this study, doctors performed cryoablation on patients whose tumors were, on average, 2.5 centimeters. The cryoablation procedure lasted for about 30 minutes, and patients were able to go home on the same day following treatment. Doctors then followed up with the patients after 16 months. In the follow-up, doctors found the recurrence rate for tumors after using cryoablation was only 10 percent.

For patients who don’t qualify for surgery, radiation and hormonal therapy is typically used to treat tumors. However, said Yolanda Brice, M.D., an interventional radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, “when treated with only radiation and hormonal therapy, the tumors will eventually return.” Cryotherapy, Brice said, could be a more effective way to treat cancer for patients who can’t have surgery.

“The fact that we only saw a 10 percent recurrence rate in our study is incredibly promising,” she said.