Genomic Data Has a Diversity Problem, But Global Efforts Are Underway to Fix It

Genetic data sets skew too European, threatening to narrow who will benefit from future advances.

Genomics has begun its golden age. Just 20 years ago, sequencing a single genome cost nearly $3 billion and took over a decade. Today, the same feat can be achieved for a few hundred dollars and the better part of a day . Suddenly, the prospect of sequencing not just individuals, but whole populations, has become feasible.

The genetic differences between humans may seem meager, only around 0.1 percent of the genome on average, but this variation can have profound effects on an individual's risk of disease, responsiveness to medication, and even the dosage level that would work best.

Already, initiatives like the U.K.'s 100,000 Genomes Project - now expanding to 1 million genomes - and other similarly massive sequencing projects in Iceland and the U.S., have begun collecting population-scale data in order to capture and study this variation.

The resulting data sets are immensely valuable to researchers and drug developers working to design new 'precision' medicines and diagnostics, and to gain insights that may benefit patients. Yet, because the majority of this data comes from developed countries with well-established scientific and medical infrastructure, the data collected so far is heavily biased towards Western populations with largely European ancestry.

This presents a startling and fast-emerging problem: groups that are under-represented in these datasets are likely to benefit less from the new wave of therapeutics, diagnostics, and insights, simply because they were tailored for the genetic profiles of people with European ancestry.

We may indeed be approaching a golden age of genomics-enabled precision medicine. But if the data bias persists then there is a risk, as with most golden ages throughout history, that the benefits will not be equally accessible to all, and existing inequalities will only be exacerbated.

To remedy the situation, a number of initiatives have sprung up to sequence genomes of under-represented groups, adding them to the datasets and ensuring that they too will benefit from the rapidly unfolding genomic revolution.

Global Gene Corp

The idea behind Global Gene Corp was born eight years ago in Harvard when Sumit Jamuar, co-founder and CEO, met up with his two other co-founders, both experienced geneticists, for a coffee.

"They were discussing the limitless applications of understanding your genetic code," said Jamuar, a business executive from New Delhi.

"And so, being a technology enthusiast type, I was excited and I turned to them and said hey, this is incredible! Could you sequence me and give me some insights? And they actually just turned around and said no, because it's not going to be useful for you - there's not enough reference for what a good Sumit looks like."

What started as a curiosity-driven conversation on the power of genomics ended with a commitment to tackle one of the field's biggest roadblocks - its lack of global representation.

Jamuar set out to begin with India, which has about 20 percent of the world's population, including over 4000 different ethnicities, but contributes less than 2 percent of genomic data, he told Leaps.org.

Eight years later, Global Gene Corp's sequencing initiative is well underway, and is the largest in the history of the Indian subcontinent. The program is being carried out in collaboration with biotech giant Regeneron, with support from the Indian government, local communities, and the Indian healthcare ecosystem. In August 2020, Global Gene Corp's work was recognized through the $1 million 2020 Roddenberry award for organizations that advance the vision of 'Star Trek' creator Gene Roddenberry to better humanity.

This problem has already begun to manifest itself in, for example, much higher levels of genetic misdiagnosis among non-Europeans tested for their risk of certain diseases, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - an inherited disease of the heart muscle.

Global Gene Corp also focuses on developing and implementing AI and machine learning tools to make sense of the deluge of genomic data. These tools are increasingly used by both industry and academia to guide future research by identifying particularly promising or clinically interesting genetic variants. But if the underlying data is skewed European, then the effectiveness of the computational analysis - along with the future advances and avenues of research that emerge from it - will be skewed towards Europeans too.

This problem has already begun to manifest itself in, for example, much higher levels of genetic misdiagnosis among non-Europeans tested for their risk of certain diseases, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - an inherited disease of the heart muscle. Most of the genetic variants used in these tests were identified as being causal for the disease from studies of European genomes. However, many of these variants differ both in their distribution and clinical significance across populations, leading to many patients of non-European ancestry receiving false-positive test results - as their benign genetic variants were misclassified as pathogenic. Had even a small number of genomes from other ethnicities been included in the initial studies, these misdiagnoses could have been avoided.

"Unless we have a data set which is unbiased and representative, we're never going to achieve the success that we want," Jamuar says.

"When Siri was first launched, she could hardly recognize an accent which was not of a certain type, so if I was trying to speak to Siri, I would have to repeat myself multiple times and try to mimic an accent which wasn't my accent so that she could understand it.

"But over time the voice recognition technology improved tremendously because the training data was expanded to include people of very diverse backgrounds and their accents, so the algorithms were trained to be able to pick that up and it dramatically improved the technology. That's the way we have to think about it - without that good-quality diverse data, we will never be able to achieve the full potential of the computational tools."

While mapping India's rich genetic diversity has been the organization's primary focus so far, they plan, in time, to expand their work to other under-represented groups in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America.

"As other like-minded people and partners join the mission, it just accelerates the achievement of what we have set out to do, which is to map out and organize the world's genomic diversity so that we can enable high-quality life and longevity benefits for everyone, everywhere," Jamuar says.

Empowering African Genomics

Africa is the birthplace of our species, and today still retains an inordinate amount of total human genetic diversity. Groups that left Africa and went on to populate the rest of the world, some 50 to 100,000 years ago, were likely small in number and only took a fraction of the total genetic diversity with them. This ancient bottleneck means that no other group in the world can match the level of genetic diversity seen in modern African populations.

Despite Africa's central importance in understanding the history and extent of human genetic diversity, the genomics of African populations remains wildly understudied. Addressing this disparity has become a central focus of the H3Africa Consortium, an initiative formally launched in 2012 with support from the African Academy of Sciences, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and the UK's Wellcome Trust. Today, H3Africa supports over 50 projects across the continent, on an array of different research areas in genetics relevant to the health and heredity of Africans.

"Africa is the cradle of Humankind. So what that really means is that the populations that are currently living in Africa are among some of the oldest populations on the globe, and we know that the longer populations have had to go through evolutionary phases, the more variation there is in the genomes of people who live presently," says Zane Lombard, a principal investigator at H3Africa and Associate Professor of Human Genetics at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa.

"So for that reason, African populations carry a huge amount of genetic variation and diversity, which is pretty much uncaptured. There's still a lot to learn as far as novel variation is concerned by looking at and studying African genomes."

A recent landmark H3Africa study, led by Lombard and published in Nature in October, sequenced the genomes of over 400 African individuals from 50 ethno-linguistic groups - many of which had never been sampled before.

Despite the relatively modest number of individuals sequenced in the study, over three million previously undescribed genetic variants were found, and complex patterns of ancestral migration were uncovered.

"In some of these ethno-linguistic groups they don't have a word for DNA, so we've had to really think about how to make sure that we communicate the purposes of different studies to participants so that you have true informed consent," says Lombard.

"The objective," she explained, "was to try and fill some of the gaps for many of these populations for which we didn't have any whole genome sequences or any genetic variation data...because if we're thinking about the future of precision medicine, if the patient is a member of a specific group where we don't know a lot about the genomic variation that exists in that group, it makes it really difficult to start thinking about clinical interpretation of their data."

From H3Africa's conception, the consortium's goal has not only been to better represent Africa's staggering genetic diversity in genomic data sets, but also to build Africa's domestic genomics capabilities and empower a new generation of African researchers. By doing so, the hope is that Africans will be able to set their own genomics agenda, and leapfrog to new and better ways of doing the work.

"The training that has happened on the continent and the number of new scientists, new students, and fellows that have come through the process and are now enabled to start their own research groups, to grow their own research in their countries, to be a spokesperson for genomics research in their countries, and to build that political will to do these larger types of sequencing initiatives - that is really a significant outcome from H3Africa as well. Over and above all the science that's coming out," Lombard says.

"What has been created through H3Africa is just this locus of researchers and scientists and bioethicists who have the same goal at heart - to work towards adjusting the data bias and making sure that all global populations are represented in genomics."

Scientists have known about and studied heart rate variability, or HRV, for a long time and, in recent years, monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately.

This episode is about a health metric you may not have heard of before: heart rate variability, or HRV. This refers to the small changes in the length of time between each of your heart beats.

Scientists have known about and studied HRV for a long time. In recent years, though, new monitors have come to market that can measure HRV accurately whenever you want.

Five months ago, I got interested in HRV as a more scientific approach to finding the lifestyle changes that work best for me as an individual. It's at the convergence of some important trends in health right now, such as health tech, precision health and the holistic approach in systems biology, which recognizes how interactions among different parts of the body are key to health.

But HRV is just one of many numbers worth paying attention to. For this episode of Making Sense of Science, I spoke with psychologist Dr. Leah Lagos; Dr. Jessilyn Dunn, assistant professor in biomedical engineering at Duke; and Jason Moore, the CEO of Spren and an app called Elite HRV. We talked about what HRV is, research on its benefits, how to measure it, whether it can be used to make improvements in health, and what researchers still need to learn about HRV.

*Talk to your doctor before trying anything discussed in this episode related to HRV and lifestyle changes to raise it.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Show notes

Spren - https://www.spren.com/

Elite HRV - https://elitehrv.com/

Jason Moore's Twitter - https://twitter.com/jasonmooreme?lang=en

Dr. Jessilyn Dunn's Twitter - https://twitter.com/drjessilyn?lang=en

Dr. Dunn's study on HRV, flu and common cold - https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/f...

Dr. Leah Lagos - https://drleahlagos.com/

Dr. Lagos on Star Talk - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jC2Q10SonV8

Research on HRV and intermittent fasting - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33859841/

Research on HRV and Mediterranean diet - https://medicalxpress.com/news/2010-06-twin-medite...:~:text=Using%20data%20from%20the%20Emory,eating%20a%20Western%2Dtype%20diet

Devices for HRV biofeedback - https://elitehrv.com/heart-variability-monitors-an...

Benefits of HRV biofeedback - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

HRV and cognitive performance - https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins...

HRV and emotional regulation - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36030986/

Fortune article on HRV - https://fortune.com/well/2022/12/26/heart-rate-var...

Peanut allergies affect about a million children in the U.S., and most never outgrow them. Luckily, some promising remedies are in the works.

Ever since he was a baby, Sharon Wong’s son Brandon suffered from rashes, prolonged respiratory issues and vomiting. In 2006, as a young child, he was diagnosed with a severe peanut allergy.

"My son had a history of reacting to traces of peanuts in the air or in food,” says Wong, a food allergy advocate who runs a blog focusing on nut free recipes, cooking techniques and food allergy awareness. “Any participation in school activities, social events, or travel with his peanut allergy required a lot of preparation.”

Peanut allergies affect around a million children in the U.S. Most never outgrow the condition. The problem occurs when the immune system mistakenly views the proteins in peanuts as a threat and releases chemicals to counteract it. This can lead to digestive problems, hives and shortness of breath. For some, like Wong’s son, even exposure to trace amounts of peanuts could be life threatening. They go into anaphylactic shock and need to take a shot of adrenaline as soon as possible.

Typically, people with peanut allergies try to completely avoid them and carry an adrenaline autoinjector like an EpiPen in case of emergencies. This constant vigilance is very stressful, particularly for parents with young children.

“The search for a peanut allergy ‘cure’ has been a vigorous one,” says Claudia Gray, a pediatrician and allergist at Vincent Pallotti Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The closest thing to a solution so far, she says, is the process of desensitization, which exposes the patient to gradually increasing doses of peanut allergen to build up a tolerance. The most common type of desensitization is oral immunotherapy, where patients ingest small quantities of peanut powder. It has been effective but there is a risk of anaphylaxis since it involves swallowing the allergen.

"By the end of the trial, my son tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts," Sharon Wong says.

DBV Technologies, a company based in Montrouge, France has created a skin patch to address this problem. The Viaskin Patch contains a much lower amount of peanut allergen than oral immunotherapy and delivers it through the skin to slowly increase tolerance. This decreases the risk of anaphylaxis.

Wong heard about the peanut patch and wanted her son to take part in an early phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds.

“We felt that participating in DBV’s peanut patch trial would give him the best chance at desensitization or at least increase his tolerance from a speck of peanut to a peanut,” Wong says. “The daily routine was quite simple, remove the old patch and then apply a new one. By the end of the trial, he tolerated approximately 1.5 peanuts.”

How it works

For DBV Technologies, it all began when pediatric gastroenterologist Pierre-Henri Benhamou teamed up with fellow professor of gastroenterology Christopher Dupont and his brother, engineer Bertrand Dupont. Together they created a more effective skin patch to detect when babies have allergies to cow's milk. Then they realized that the patch could actually be used to treat allergies by promoting tolerance. They decided to focus on peanut allergies first as the more dangerous.

The Viaskin patch utilizes the fact that the skin can promote tolerance to external stimuli. The skin is the body’s first defense. Controlling the extent of the immune response is crucial for the skin. So it has defense mechanisms against external stimuli and can promote tolerance.

The patch consists of an adhesive foam ring with a plastic film on top. A small amount of peanut protein is placed in the center. The adhesive ring is attached to the back of the patient's body. The peanut protein sits above the skin but does not directly touch it. As the patient sweats, water droplets on the inside of the film dissolve the peanut protein, which is then absorbed into the skin.

The peanut protein is then captured by skin cells called Langerhans cells. They play an important role in getting the immune system to tolerate certain external stimuli. Langerhans cells take the peanut protein to lymph nodes which activate T regulatory cells. T regulatory cells suppress the allergic response.

A different patch is applied to the skin every day to increase tolerance. It’s both easy to use and convenient.

“The DBV approach uses much smaller amounts than oral immunotherapy and works through the skin significantly reducing the risk of allergic reactions,” says Edwin H. Kim, the division chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at the University of North Carolina, U.S., and one of the principal investigators of Viaskin’s clinical trials. “By not going through the mouth, the patch also avoids the taste and texture issues. Finally, the ability to apply a patch and immediately go about your day may be very attractive to very busy patients and families.”

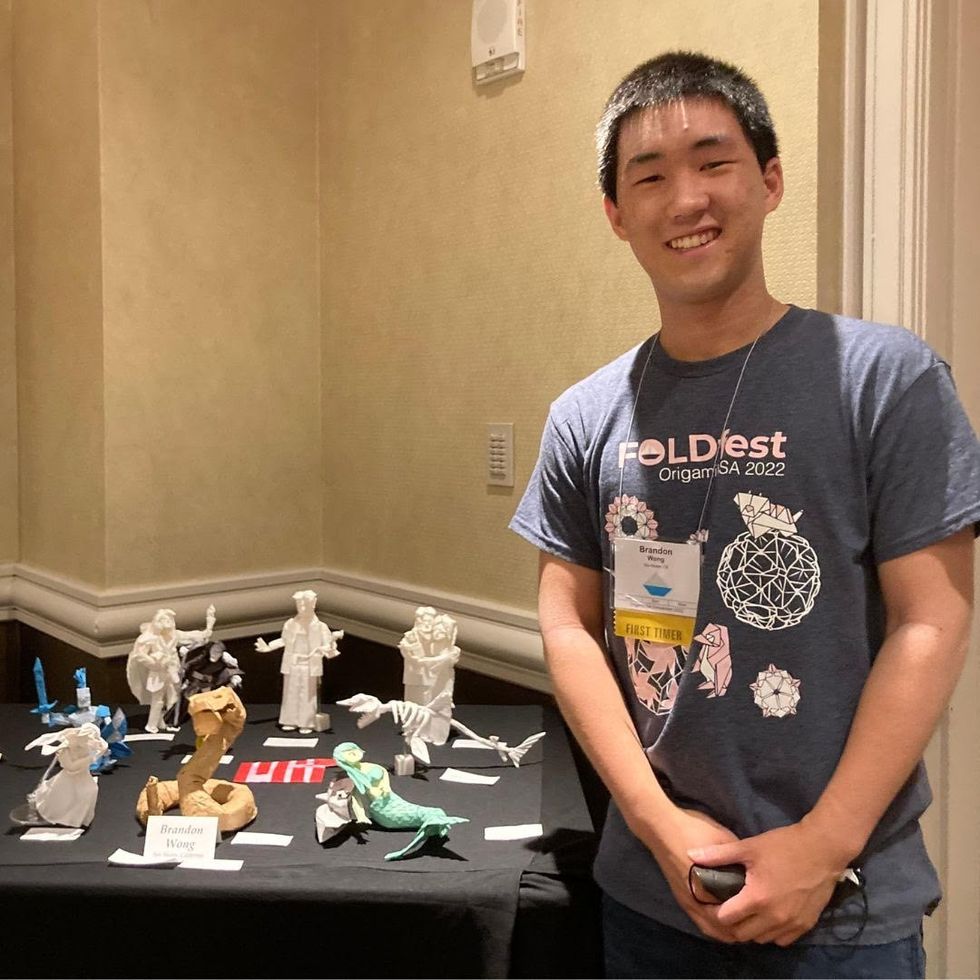

Brandon Wong displaying origami figures he folded at an Origami Convention in 2022

Sharon Wong

Clinical trials

Results from DBV's phase 3 trial in children ages 1 to 3 show its potential. For a positive result, patients who could not tolerate 10 milligrams or less of peanut protein had to be able to manage 300 mg or more after 12 months. Toddlers who could already tolerate more than 10 mg needed to be able to manage 1000 mg or more. In the end, 67 percent of subjects using the Viaskin patch met the target as compared to 33 percent of patients taking the placebo dose.

“The Viaskin peanut patch has been studied in several clinical trials to date with promising results,” says Suzanne M. Barshow, assistant professor of medicine in allergy and asthma research at Stanford University School of Medicine in the U.S. “The data shows that it is safe and well-tolerated. Compared to oral immunotherapy, treatment with the patch results in fewer side effects but appears to be less effective in achieving desensitization.”

The primary reason the patch is less potent is that oral immunotherapy uses a larger amount of the allergen. Additionally, absorption of the peanut protein into the skin could be erratic.

Gray also highlights that there is some tradeoff between risk and efficacy.

“The peanut patch is an exciting advance but not as effective as the oral route,” Gray says. “For those patients who are very sensitive to orally ingested peanut in oral immunotherapy or have an aversion to oral peanut, it has a use. So, essentially, the form of immunotherapy will have to be tailored to each patient.” Having different forms such as the Viaskin patch which is applied to the skin or pills that patients can swallow or dissolve under the tongue is helpful.

The hope is that the patch’s efficacy will increase over time. The team is currently running a follow-up trial, where the same patients continue using the patch.

“It is a very important study to show whether the benefit achieved after 12 months on the patch stays stable or hopefully continues to grow with longer duration,” says Kim, who is an investigator in this follow-up trial.

"My son now attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He has so much more freedom," Wong says.

The team is further ahead in the phase 3 follow-up trial for 4-to-11-year-olds. The initial phase 3 trial was not as successful as the trial for kids between one and three. The patch enabled patients to tolerate more peanuts but there was not a significant enough difference compared to the placebo group to be definitive. The follow-up trial showed greater potency. It suggests that the longer patients are on the patch, the stronger its effects.

They’re also testing if making the patch bigger, changing the shape and extending the minimum time it’s worn can improve its benefits in a trial for a new group of 4-to-11 year-olds.

The future

DBV Technologies is using the skin patch to treat cow’s milk allergies in children ages 1 to 17. They’re currently in phase 2 trials.

As for the peanut allergy trials in toddlers, the hope is to see more efficacy soon.

For Wong’s son who took part in the earlier phase 2 trial for 4-to-11-year-olds, the patch has transformed his life.

“My son continues to maintain his peanut tolerance and is not affected by peanut dust in the air or cross-contact,” Wong says. ”He attends university in Massachusetts, lives on-campus, and eats dorm food. He still carries an EpiPen but has so much more freedom than before his clinical trial. We will always be grateful.”