Genetic Test Scores Predicting Intelligence Are Not the New Eugenics

A thinking person.

"A world where people are slotted according to their inborn ability – well, that is Gattaca. That is eugenics."

This was the assessment of Dr. Catherine Bliss, a sociologist who wrote a new book on social science genetics, when asked by MIT Technology Review about polygenic scores that can predict a person's intelligence or performance in school. Like a credit score, a polygenic score is statistical tool that combines a lot of information about a person's genome into a single number. Fears about using polygenic scores for genetic discrimination are understandable, given this country's ugly history of using the science of heredity to justify atrocities like forcible sterilization. But polygenic scores are not the new eugenics. And, rushing to discuss polygenic scores in dystopian terms only contributes to widespread public misunderstanding about genetics.

Can we start genotyping toddlers to identify the budding geniuses among them? The short answer is no.

Let's begin with some background on how polygenic scores are developed. In a genome wide-association study, researchers conduct millions of statistical tests to identify small differences in people's DNA sequence that are correlated with differences in a target outcome (beyond what can attributed to chance or ancestry differences). Successful studies of this sort require enormous sample sizes, but companies like 23andMe are now contributing genetic data from their consumers to research studies, and national biorepositories like U.K. Biobank have put genetic information from hundreds of thousands of people online. When applied to studying blood lipids or myopia, this kind of study strikes people as a straightforward and uncontroversial scientific tool. But it can also be conducted for cognitive and behavioral outcomes, like how many years of school a person has completed. When researchers have finished a genome-wide association study, they are left with a dataset with millions of rows (one for each genetic variant analyzed) and one column with the correlations between each variant and the outcome being studied.

The trick to polygenic scoring is to use these results and apply them to people who weren't participants in the original study. Measure the genes of a new person, weight each one of her millions of genetic variants by its correlation with educational attainment from a genome-wide association study, and then simply add everything up into a single number. Voila! -- you've created a polygenic score for educational attainment. On its face, the idea of "scoring" a person's genotype does immediately suggest Gattaca-type applications. Can we now start screening embryos for their "inborn ability," as Bliss called it? Can we start genotyping toddlers to identify the budding geniuses among them?

The short answer is no. Here are four reasons why dystopian projections about polygenic scores are out of touch with the current science:

The phrase "DNA tests for IQ" makes for an attention-grabbing headline, but it's scientifically meaningless.

First, a polygenic score currently predicts the life outcomes of an individual child with a great deal of uncertainty. The amount of uncertainty around polygenic predictions will decrease in the future, as genetic discovery samples get bigger and genetic studies include more of the variation in the genome, including rare variants that are particular to a few families. But for now, knowing a child's polygenic score predicts his ultimate educational attainment about as well as knowing his family's income, and slightly worse than knowing how far his mother went in school. These pieces of information are also readily available about children before they are born, but no one is writing breathless think-pieces about the dystopian outcomes that will result from knowing whether a pregnant woman graduated from college.

Second, using polygenic scoring for embryo selection requires parents to create embryos using reproductive technology, rather than conceiving them by having sex. The prediction that many women will endure medically-unnecessary IVF, in order to select the embryo with the highest polygenic score, glosses over the invasiveness, indignity, pain, and heartbreak that these hormonal and surgical procedures can entail.

Third, and counterintuitively, a polygenic score might be using DNA to measure aspects of the child's environment. Remember, a child inherits her DNA from her parents, who typically also shape the environment she grows up in. And, children's environments respond to their unique personalities and temperaments. One Icelandic study found that parents' polygenic scores predicted their children's educational attainment, even if the score was constructed using only the half of the parental genome that the child didn't inherit. For example, imagine mom has genetic variant X that makes her more likely to smoke during her pregnancy. Prenatal exposure to nicotine, in turn, affects the child's neurodevelopment, leading to behavior problems in school. The school responds to his behavioral problems with suspension, causing him to miss out on instructional content. A genome-wide association study will collapse this long and winding causal path into a simple correlation -- "genetic variant X is correlated with academic achievement." But, a child's polygenic score, which includes variant X, will partly reflect his likelihood of being exposed to adverse prenatal and school environments.

Finally, the phrase "DNA tests for IQ" makes for an attention-grabbing headline, but it's scientifically meaningless. As I've written previously, it makes sense to talk about a bacterial test for strep throat, because strep throat is a medical condition defined as having streptococcal bacteria growing in the back of your throat. If your strep test is positive, you have strep throat, no matter how serious your symptoms are. But a polygenic score is not a test "for" IQ, because intelligence is not defined at the level of someone's DNA. It doesn't matter how high your polygenic score is, if you can't reason abstractly or learn from experience. Equating your intelligence, a cognitive capacity that is tested behaviorally, with your polygenic score, a number that is a weighted sum of genetic variants discovered to be statistically associated with educational attainment in a hypothesis-free data mining exercise, is misleading about what intelligence is and is not.

The task for many scientists like me, who are interested in understanding why some children do better in school than other children, is to disentangle correlations from causation.

So, if we're not going to build a Gattaca-style genetic hierarchy, what are polygenic scores good for? They are not useless. In fact, they give scientists a valuable new tool for studying how to improve children's lives. The task for many scientists like me, who are interested in understanding why some children do better in school than other children, is to disentangle correlations from causation. The best way to do that is to run an experiment where children are randomized to environments, but often a true experiment is unethical or impractical. You can't randomize children to be born to a teenage mother or to go to school with inexperienced teachers. By statistically controlling for some of the relevant genetic differences between people using a polygenic score, scientists are better able to identify potential environmental causes of differences in children's life outcomes. As we have seen with other methods from genetics, like twin studies, understanding genes illuminates the environment.

Research that examines genetics in relation to social inequality, such as differences in higher education outcomes, will obviously remind people of the horrors of the eugenics movement. Wariness regarding how genetic science will be applied is certainly warranted. But, polygenic scores are not pure measures of "inborn ability," and genome-wide association studies of human intelligence and educational attainment are not inevitably ushering in a new eugenics age.

Bivalent Boosters for Young Children Are Elusive. The Search Is On for Ways to Improve Access.

Theo, an 18-month-old in rural Nebraska, walks with his father in their backyard. For many toddlers, the barriers to accessing COVID-19 vaccines are many, such as few locations giving vaccines to very young children.

It’s Theo’s* first time in the snow. Wide-eyed, he totters outside holding his father’s hand. Sarah Holmes feels great joy in watching her 18-month-old son experience the world, “His genuine wonder and excitement gives me so much hope.”

In the summer of 2021, two months after Theo was born, Holmes, a behavioral health provider in Nebraska lost her grandparents to COVID-19. Both were vaccinated and thought they could unmask without any risk. “My grandfather was a veteran, and really trusted the government and faith leaders saying that COVID-19 wasn’t a threat anymore,” she says.” The state of emergency in Louisiana had ended and that was the message from the people they respected. “That is what killed them.”

The current official public health messaging is that regardless of what variant is circulating, the best way to be protected is to get vaccinated. These warnings no longer mention masking, or any of the other Swiss-cheese layers of mitigation that were prevalent in the early days of this ongoing pandemic.

The problem with the prevailing, vaccine centered strategy is that if you are a parent with children under five, barriers to access are real. In many cases, meaningful tools and changes that would address these obstacles are lacking, such as offering vaccines at more locations, mandating masks at these sites, and providing paid leave time to get the shots.

Children are at risk

Data presented at the most recent FDA advisory panel on COVID-19 vaccines showed that in the last year infants under six months had the third highest rate of hospitalization. “From the beginning, the message has been that kids don’t get COVID, and then the message was, well kids get COVID, but it’s not serious,” says Elias Kass, a pediatrician in Seattle. “Then they waited so long on the initial vaccines that by the time kids could get vaccinated, the majority of them had been infected.”

A closer look at the data from the CDC also reveals that from January 2022 to January 2023 children aged 6 to 23 months were more likely to be hospitalized than all other vaccine eligible pediatric age groups.

“We sort of forced an entire generation of kids to be infected with a novel virus and just don't give a shit, like nobody cares about kids,” Kass says. In some cases, COVID has wreaked havoc with the immune systems of very young children at his practice, making them vulnerable to other illnesses, he said. “And now we have kids that have had COVID two or three times, and we don’t know what is going to happen to them.”

Jumping through hurdles

Children under five were the last group to have an emergency use authorization (EUA) granted for the COVID-19 vaccine, a year and a half after adult vaccine approval. In June 2022, 30,000 sites were initially available for children across the country. Six months later, when boosters became available, there were only 5,000.

Currently, only 3.8% of children under two have completed a primary series, according to the CDC. An even more abysmal 0.2% under two have gotten a booster.

Ariadne Labs, a health center affiliated with Harvard, is trying to understand why these gaps exist. In conjunction with Boston Children’s Hospital, they have created a vaccine equity planner that maps the locations of vaccine deserts based on factors such as social vulnerability indexes and transportation access.

“People are having to travel farther because the sites are just few and far between,” says Benjy Renton, a research assistant at Ariadne.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. When the boosters first came out she expected her toddler could get it close to home, but her husband had to drive Charlee four hours roundtrip.

This experience hasn’t been uncommon, especially in rural parts of the U.S. If parents wanted vaccines for their young children shortly after approval, they faced the prospect of loading babies and toddlers, famous for their calm demeanor, into cars for lengthy rides. The situation continues today. Mrs. Smith*, a grant writer and non-profit advisor who lives in Idaho, is still unable to get her child the bivalent booster because a two-hour one-way drive in winter weather isn’t possible.

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited.

Protect Their Future (PTF), a grassroots organization focusing on advocacy for the health care of children, hears from parents several times a week who are having trouble finding vaccines. The vaccine rollout “has been a total mess,” says Tamara Lea Spira, co-founder of PTF “It’s been very hard for people to access vaccines for children, particularly those under three.”

Seventeen states have passed laws that give pharmacists authority to vaccinate as young as six months. Under federal law, the minimum age in other states is three. Even in the states that allow vaccination of toddlers, each pharmacy chain varies. Some require prescriptions.

It takes time to make phone calls to confirm availability and book appointments online. “So it means that the parents who are getting their children vaccinated are those who are even more motivated and with the time and the resources to understand whether and how their kids can get vaccinated,” says Tiffany Green, an associate professor in population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Green adds, “And then we have the contraction of vaccine availability in terms of sites…who is most likely to be affected? It's the usual suspects, children of color, disabled children, low-income children.”

It can be more difficult for low wage earners to take time off, which poses challenges especially in a number of rural counties across the country, where weekend hours for getting the shots may be limited. In Bibb County, Ala., vaccinations take place only on Wednesdays from 1:45 to 3:00 pm.

“People who are focused on putting food on the table or stressed about having enough money to pay rent aren't going to prioritize getting vaccinated that day,” says Julia Raifman, assistant professor of health law, policy and management at Boston University. She created the COVID-19 U.S. State Policy Database, which tracks state health and economic policies related to the pandemic.

Most states in the U.S. lack paid sick leave policies, and the average paid sick days with private employers is about one week. Green says, “I think COVID should have been a wake-up call that this is necessary.”

Maskless waiting rooms

For her son, Holmes spent hours making phone calls but could uncover no clear answers. No one could estimate an arrival date for the booster. “It disappoints me greatly that the process for locating COVID-19 vaccinations for young children requires so much legwork in terms of time and resources,” she says.

In January, she found a pharmacy 30 minutes away that could vaccinate Theo. With her son being too young to mask, she waited in the car with him as long as possible to avoid a busy, maskless waiting room.

Kids under two, such as Theo, are advised not to wear masks, which make it too hard for them to breathe. With masking policies a rarity these days, waiting rooms for vaccines present another barrier to access. Even in healthcare settings, current CDC guidance only requires masking during high transmission or when treating COVID positive patients directly.

“This is a group that is really left behind,” says Raifman. “They cannot wear masks themselves. They really depend on others around them wearing masks. There's not even one train car they can go on if their parents need to take public transportation… and not risk COVID transmission.”

Yet another challenge is presented for those who don’t speak English or Spanish. According to Translators without Borders, 65 million people in America speak a language other than English. Most state departments of health have a COVID-19 web page that redirects to the federal vaccines.gov in English, with an option to translate to Spanish only.

The main avenue for accessing information on vaccines relies on an internet connection, but 22 percent of rural Americans lack broadband access. “People who lack digital access, or don’t speak English…or know how to navigate or work with computers are unable to use that service and then don’t have access to the vaccines because they just don’t know how to get to them,” Jirmanus, an affiliate of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard and a member of The People’s CDC explains. She sees this issue frequently when working with immigrant communities in Massachusetts. “You really have to meet people where they’re at, and that means physically where they’re at.”

Equitable solutions

Grassroots and advocacy organizations like PTF have been filling a lot of the holes left by spotty federal policy. “In many ways this collective care has been as important as our gains to access the vaccine itself,” says Spira, the PTF co-founder.

PTF facilitates peer-to-peer networks of parents that offer support to each other. At least one parent in the group has crowdsourced information on locations that are providing vaccines for the very young and created a spreadsheet displaying vaccine locations. “It is incredible to me still that this vacuum of information and support exists, and it took a totally grassroots and volunteer effort of parents and physicians to try and respond to this need.” says Spira.

Kass, who is also affiliated with PTF, has been vaccinating any child who comes to his independent practice, regardless of whether they’re one of his patients or have insurance. “I think putting everything on retail pharmacies is not appropriate. By the time the kids' vaccines were released, all of our mass vaccination sites had been taken down.” A big way to help parents and pediatricians would be to allow mixing and matching. Any child who has had the full Pfizer series has had to forgo a bivalent booster.

“I think getting those first two or three doses into kids should still be a priority, and I don’t want to lose sight of all that,” states Renton, the researcher at Ariadne Labs. Through the vaccine equity planner, he has been trying to see if there are places where mobile clinics can go to improve access. Renton continues to work with local and state planners to aid in vaccine planning. “I think any way we can make that process a lot easier…will go a long way into building vaccine confidence and getting people vaccinated,” Renton says.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch, a pharmacist, and her two-year-old daughter, Charlee, live in Iowa. Her husband had to drive four hours roundtrip to get the boosters for Charlee.

Michelle Baltes-Breitwisch

Other changes need to come from the CDC. Even though the CDC “has this historic reputation and a mission of valuing equity and promoting health,” Jirmanus says, “they’re really failing. The emphasis on personal responsibility is leaving a lot of people behind.” She believes another avenue for more equitable access is creating legislation for upgraded ventilation in indoor public spaces.

Given the gaps in state policies, federal leadership matters, Raifman says. With the FDA leaning toward a yearly COVID vaccine, an equity lens from the CDC will be even more critical. “We can have data driven approaches to using evidence based policies like mask policies, when and where they're most important,” she says. Raifman wants to see a sustainable system of vaccine delivery across the country complemented with a surge preparedness plan.

With the public health emergency ending and vaccines going to the private market sometime in 2023, it seems unlikely that vaccine access is going to improve. Now more than ever, ”We need to be able to extend to people the choice of not being infected with COVID,” Jirmanus says.

*Some names were changed for privacy reasons.

Last month, a paper published in Cell by Harvard biologist David Sinclair explored root cause of aging, as well as examining whether this process can be controlled. We talked with Dr. Sinclair about this new research.

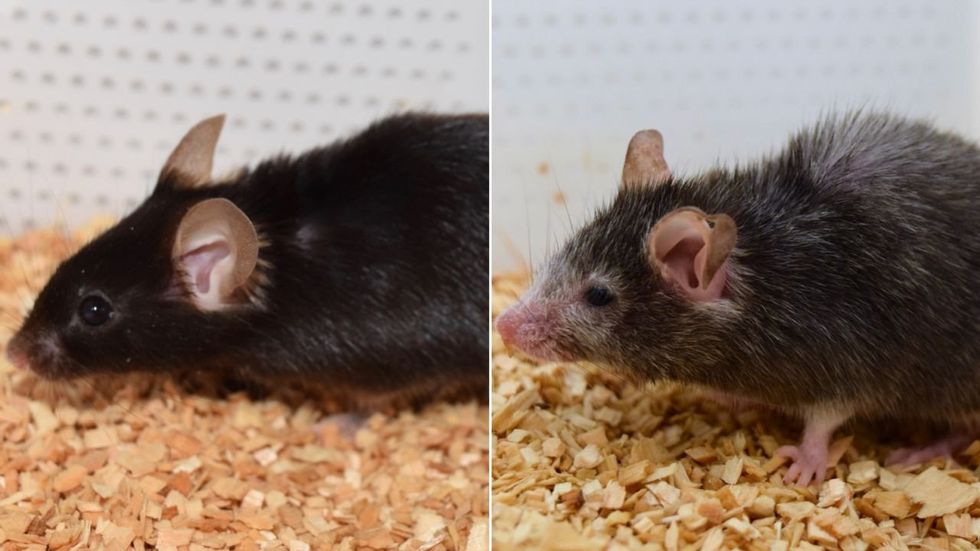

What causes aging? In a paper published last month, Dr. David Sinclair, Professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, reports that he and his co-authors have found the answer. Harnessing this knowledge, Dr. Sinclair was able to reverse this process, making mice younger, according to the study published in the journal Cell.

I talked with Dr. Sinclair about his new study for the latest episode of Making Sense of Science. Turning back the clock on mouse age through what’s called epigenetic reprogramming – and understanding why animals get older in the first place – are key steps toward finding therapies for healthier aging in humans. We also talked about questions that have been raised about the research.

Show links:

Dr. Sinclair's paper, published last month in Cell.

Recent pre-print paper - not yet peer reviewed - showing that mice treated with Yamanaka factors lived longer than the control group.

Dr. Sinclair's podcast.

Previous research on aging and DNA mutations.

Dr. Sinclair's book, Lifespan.

Harvard Medical School