Genetic Test Scores Predicting Intelligence Are Not the New Eugenics

A thinking person.

"A world where people are slotted according to their inborn ability – well, that is Gattaca. That is eugenics."

This was the assessment of Dr. Catherine Bliss, a sociologist who wrote a new book on social science genetics, when asked by MIT Technology Review about polygenic scores that can predict a person's intelligence or performance in school. Like a credit score, a polygenic score is statistical tool that combines a lot of information about a person's genome into a single number. Fears about using polygenic scores for genetic discrimination are understandable, given this country's ugly history of using the science of heredity to justify atrocities like forcible sterilization. But polygenic scores are not the new eugenics. And, rushing to discuss polygenic scores in dystopian terms only contributes to widespread public misunderstanding about genetics.

Can we start genotyping toddlers to identify the budding geniuses among them? The short answer is no.

Let's begin with some background on how polygenic scores are developed. In a genome wide-association study, researchers conduct millions of statistical tests to identify small differences in people's DNA sequence that are correlated with differences in a target outcome (beyond what can attributed to chance or ancestry differences). Successful studies of this sort require enormous sample sizes, but companies like 23andMe are now contributing genetic data from their consumers to research studies, and national biorepositories like U.K. Biobank have put genetic information from hundreds of thousands of people online. When applied to studying blood lipids or myopia, this kind of study strikes people as a straightforward and uncontroversial scientific tool. But it can also be conducted for cognitive and behavioral outcomes, like how many years of school a person has completed. When researchers have finished a genome-wide association study, they are left with a dataset with millions of rows (one for each genetic variant analyzed) and one column with the correlations between each variant and the outcome being studied.

The trick to polygenic scoring is to use these results and apply them to people who weren't participants in the original study. Measure the genes of a new person, weight each one of her millions of genetic variants by its correlation with educational attainment from a genome-wide association study, and then simply add everything up into a single number. Voila! -- you've created a polygenic score for educational attainment. On its face, the idea of "scoring" a person's genotype does immediately suggest Gattaca-type applications. Can we now start screening embryos for their "inborn ability," as Bliss called it? Can we start genotyping toddlers to identify the budding geniuses among them?

The short answer is no. Here are four reasons why dystopian projections about polygenic scores are out of touch with the current science:

The phrase "DNA tests for IQ" makes for an attention-grabbing headline, but it's scientifically meaningless.

First, a polygenic score currently predicts the life outcomes of an individual child with a great deal of uncertainty. The amount of uncertainty around polygenic predictions will decrease in the future, as genetic discovery samples get bigger and genetic studies include more of the variation in the genome, including rare variants that are particular to a few families. But for now, knowing a child's polygenic score predicts his ultimate educational attainment about as well as knowing his family's income, and slightly worse than knowing how far his mother went in school. These pieces of information are also readily available about children before they are born, but no one is writing breathless think-pieces about the dystopian outcomes that will result from knowing whether a pregnant woman graduated from college.

Second, using polygenic scoring for embryo selection requires parents to create embryos using reproductive technology, rather than conceiving them by having sex. The prediction that many women will endure medically-unnecessary IVF, in order to select the embryo with the highest polygenic score, glosses over the invasiveness, indignity, pain, and heartbreak that these hormonal and surgical procedures can entail.

Third, and counterintuitively, a polygenic score might be using DNA to measure aspects of the child's environment. Remember, a child inherits her DNA from her parents, who typically also shape the environment she grows up in. And, children's environments respond to their unique personalities and temperaments. One Icelandic study found that parents' polygenic scores predicted their children's educational attainment, even if the score was constructed using only the half of the parental genome that the child didn't inherit. For example, imagine mom has genetic variant X that makes her more likely to smoke during her pregnancy. Prenatal exposure to nicotine, in turn, affects the child's neurodevelopment, leading to behavior problems in school. The school responds to his behavioral problems with suspension, causing him to miss out on instructional content. A genome-wide association study will collapse this long and winding causal path into a simple correlation -- "genetic variant X is correlated with academic achievement." But, a child's polygenic score, which includes variant X, will partly reflect his likelihood of being exposed to adverse prenatal and school environments.

Finally, the phrase "DNA tests for IQ" makes for an attention-grabbing headline, but it's scientifically meaningless. As I've written previously, it makes sense to talk about a bacterial test for strep throat, because strep throat is a medical condition defined as having streptococcal bacteria growing in the back of your throat. If your strep test is positive, you have strep throat, no matter how serious your symptoms are. But a polygenic score is not a test "for" IQ, because intelligence is not defined at the level of someone's DNA. It doesn't matter how high your polygenic score is, if you can't reason abstractly or learn from experience. Equating your intelligence, a cognitive capacity that is tested behaviorally, with your polygenic score, a number that is a weighted sum of genetic variants discovered to be statistically associated with educational attainment in a hypothesis-free data mining exercise, is misleading about what intelligence is and is not.

The task for many scientists like me, who are interested in understanding why some children do better in school than other children, is to disentangle correlations from causation.

So, if we're not going to build a Gattaca-style genetic hierarchy, what are polygenic scores good for? They are not useless. In fact, they give scientists a valuable new tool for studying how to improve children's lives. The task for many scientists like me, who are interested in understanding why some children do better in school than other children, is to disentangle correlations from causation. The best way to do that is to run an experiment where children are randomized to environments, but often a true experiment is unethical or impractical. You can't randomize children to be born to a teenage mother or to go to school with inexperienced teachers. By statistically controlling for some of the relevant genetic differences between people using a polygenic score, scientists are better able to identify potential environmental causes of differences in children's life outcomes. As we have seen with other methods from genetics, like twin studies, understanding genes illuminates the environment.

Research that examines genetics in relation to social inequality, such as differences in higher education outcomes, will obviously remind people of the horrors of the eugenics movement. Wariness regarding how genetic science will be applied is certainly warranted. But, polygenic scores are not pure measures of "inborn ability," and genome-wide association studies of human intelligence and educational attainment are not inevitably ushering in a new eugenics age.

The future of non-hormonal birth control: Antibodies can stop sperm in their tracks

Many women want non-hormonal birth control. A 22-year-old's findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

Unwanted pregnancy can now be added to the list of preventions that antibodies may be fighting in the near future. For decades, really since the 1980s, engineered monoclonal antibodies have been knocking out invading germs — preventing everything from cancer to COVID. Sperm, which have some of the same properties as germs, may be next.

Not only is there an unmet need on the market for alternatives to hormonal contraceptives, the genesis for the original research was personal for the then 22-year-old scientist who led it. Her findings were used to launch a company that could, within the decade, bring a new kind of contraceptive to the marketplace.

The genesis

It’s Suruchi Shrestha’s research — published in Science Translational Medicine in August 2021 and conducted as part of her dissertation while she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — that could change the future of contraception for many women worldwide. According to a Guttmacher Institute report, in the U.S. alone, there were 46 million sexually active women of reproductive age (15–49) who did not want to get pregnant in 2018. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade this year, Shrestha’s research could, indeed, be life changing for millions of American women and their families.

Now a scientist with NextVivo, Shrestha is not directly involved in the development of the contraceptive that is based on her research. But, back in 2016 when she was going through her own problems with hormonal contraceptives, she “was very personally invested” in her research project, Shrestha says. She was coping with a long list of negative effects from an implanted hormonal IUD. According to the Mayo Clinic, those can include severe pelvic pain, headaches, acute acne, breast tenderness, irregular bleeding and mood swings. After a year, she had the IUD removed, but it took another full year before all the side effects finally subsided; she also watched her sister suffer the “same tribulations” after trying a hormonal IUD, she says.

For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, Shrestha says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

Shrestha unshelved antibody research that had been sitting idle for decades. It was in the late 80s that scientists in Japan first tried to develop anti-sperm antibodies for contraceptive use. But, 35 years ago, “Antibody production had not been streamlined as it is now, so antibodies were very expensive,” Shrestha explains. So, they shifted away from birth control, opting to focus on developing antibodies for vaccines.

Over the course of the last three decades, different teams of researchers have been working to make the antibody more effective, bringing the cost down, though it’s still expensive, according to Shrestha. For contraceptive use either daily or monthly, she says, “You want the antibody to be very potent and also cheap.” That was her goal when she launched her study.

The problem

The problem with contraceptives for women, Shrestha says, is that all but a few of them are hormone-based or have other negative side effects. In fact, some studies and reports show that millions of women risk unintended pregnancy because of medical contraindications with hormone-based contraceptives or to avoid the risks and side effects. While there are about a dozen contraceptive choices for women, there are two for men: the condom, considered 98% effective if used correctly, and vasectomy, 99% effective. Neither of these choices are hormone-based.

On the non-hormonal side for women, there is the diaphragm which is considered only 87 percent effective. It works better with the addition of spermicides — Nonoxynol-9, or N-9 — however, they are detergents; they not only kill the sperm, they also erode the vaginal epithelium. And, there’s the non-hormonal IUD which is 99% effective. However, the IUD needs to be inserted by a medical professional, and it has a number of negative side effects, including painful cramping at a higher frequency and extremely heavy or “abnormal” and unpredictable menstrual flows.

The hormonal version of the IUD, also considered 99% effective, is the one Shrestha used which caused her two years of pain. Of course, there’s the pill, which needs to be taken daily, and the birth control ring which is worn 24/7. Both cause side effects similar to the other hormonal contraceptives on the market. The ring is considered 93% effective mostly because of user error; the pill is considered 99% effective if taken correctly.

“That’s where we saw this opening or gap for women. We want a safe, non-hormonal contraceptive,” Shrestha says. Compounding the lack of good choices, is poor access to quality sex education and family planning information, according to the non-profit Urban Institute. A focus group survey suggested that the sex education women received “often lacked substance, leaving them feeling unprepared to make smart decisions about their sexual health and safety,” wrote the authors of the Urban Institute report. In fact, nearly half (45%, or 2.8 million) of the pregnancies that occur each year in the US are unintended, reports the Guttmacher Institute. Globally the numbers are similar. According to a new report by the United Nations, each year there are 121 million unintended pregnancies, worldwide.

The science

The early work on antibodies as a contraceptive had been inspired by women with infertility. It turns out that 9 to 12 percent of women who are treated for infertility have antibodies that develop naturally and work against sperm. Shrestha was encouraged that the antibodies were specific to the target — sperm — and therefore “very safe to use in women.” She aimed to make the antibodies more stable, more effective and less expensive so they could be more easily manufactured.

Since antibodies tend to stick to things that you tell them to stick to, the idea was, basically, to engineer antibodies to stick to sperm so they would stop swimming. Shrestha and her colleagues took the binding arm of an antibody that they’d isolated from an infertile woman. Then, targeting a unique surface antigen present on human sperm, they engineered a panel of antibodies with as many as six to 10 binding arms — “almost like tongs with prongs on the tongs, that bind the sperm,” explains Shrestha. “We decided to add those grabbers on top of it, behind it. So it went from having two prongs to almost 10. And the whole goal was to have so many arms binding the sperm that it clumps it” into a “dollop,” explains Shrestha, who earned a patent on her research.

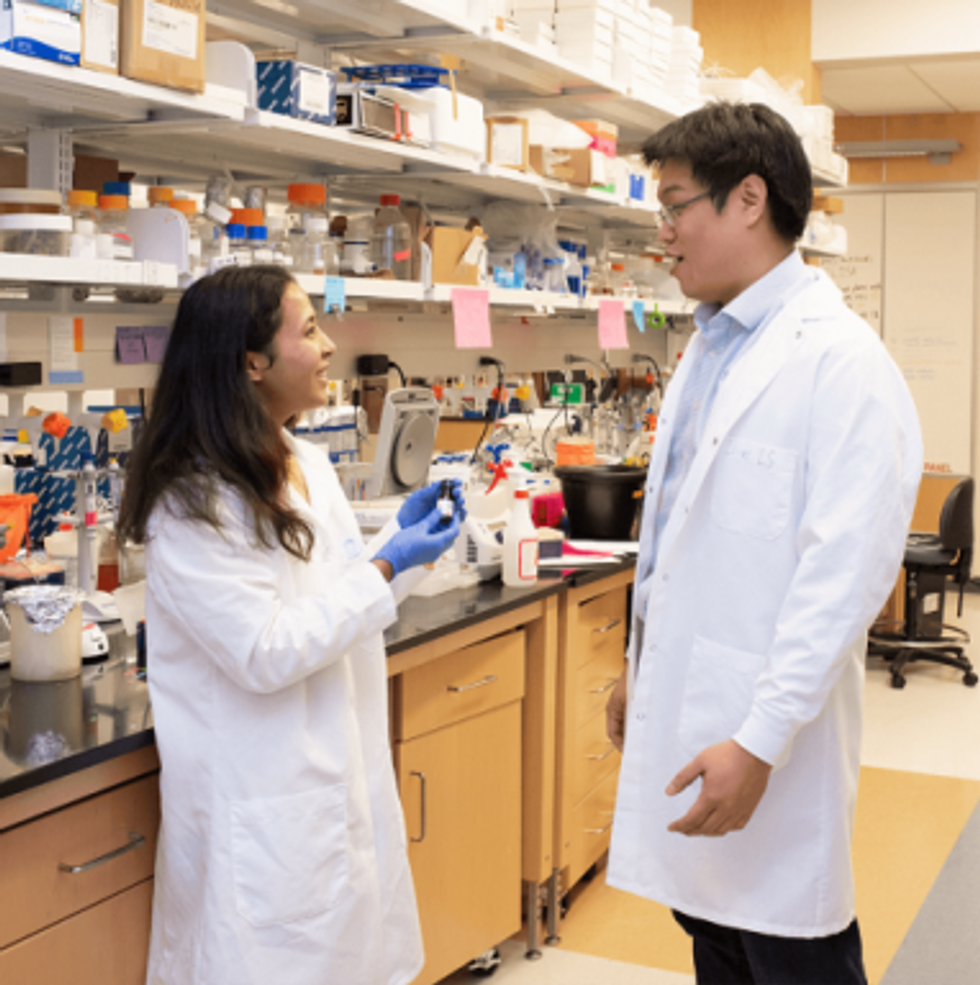

Suruchi Shrestha works in the lab with a colleague. In 2016, her research on antibodies for birth control was inspired by her own experience with side effects from an implanted hormonal IUD.

UNC - Chapel Hill

The sperm stays right where it met the antibody, never reaching the egg for fertilization. Eventually, and naturally, “Our vaginal system will just flush it out,” Shrestha explains.

“She showed in her early studies that [she] definitely got the sperm immotile, so they didn't move. And that was a really promising start,” says Jasmine Edelstein, a scientist with an expertise in antibody engineering who was not involved in this research. Shrestha’s team at UNC reproduced the effect in the sheep, notes Edelstein, who works at the startup Be Biopharma. In fact, Shrestha’s anti-sperm antibodies that caused the sperm to agglutinate, or clump together, were 99.9% effective when delivered topically to the sheep’s reproductive tracts.

The future

Going forward, Shrestha thinks the ideal approach would be delivering the antibodies through a vaginal ring. “We want to use it at the source of the spark,” Shrestha says, as opposed to less direct methods, such as taking a pill. The ring would dissolve after one month, she explains, “and then you get another one.”

Engineered to have a long shelf life, the anti-sperm antibody ring could be purchased without a prescription, and women could insert it themselves, without a doctor. “That's our hope, so that it is accessible,” Shrestha says. “Anybody can just go and grab it and not worry about pregnancy or unintended pregnancy.”

Her patented research has been licensed by several biotech companies for clinical trials. A number of Shrestha’s co-authors, including her lab advisor, Sam Lai, have launched a company, Mucommune, to continue developing the contraceptives based on these antibodies.

And, results from a small clinical trial run by researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine show that a dissolvable vaginal film with antibodies was safe when tested on healthy women of reproductive age. That same group of researchers earlier this year received a $7.2 million grant from the National Institute of Health for further research on monoclonal antibody-based contraceptives, which have also been shown to block transmission of viruses, like HIV.

“As the costs come down, this becomes a more realistic option potentially for women,” says Edelstein. “The impact could be tremendous.”

The Friday Five: An mRNA vaccine works against cancer, new research suggests

In this week's Friday Five, an mRNA vaccine works against cancer for the first time. Plus, these cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power, a new theory for what causes aging, bacteria that could get you excited to work out, and a reason for sex differences in Alzheimer's.

The Friday Five covers five stories in research that you may have missed this week. There are plenty of controversies and troubling ethical issues in science – and we get into many of them in our online magazine – but this news roundup focuses on scientific creativity and progress to give you a therapeutic dose of inspiration headed into the weekend.

Listen on Apple | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Stitcher | Listen on Amazon | Listen on Google

Here are the promising studies covered in this week's Friday Five:

- An mRNA vaccine that works against cancer

- These cameras inside the body have an unusual source of power

- A new theory for what causes aging

- Can bacteria make you excited to work out?

- Why women get Alzheimer's more often than men