Genetically Sequencing Healthy Babies Yielded Surprising Results

A newborn and mother in the hospital - first touch. (© martin81/Shutterstock)

Today in Melrose, Massachusetts, Cora Stetson is the picture of good health, a bubbly precocious 2-year-old. But Cora has two separate mutations in the gene that produces a critical enzyme called biotinidase and her body produces only 40 percent of the normal levels of that enzyme.

In the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach.

That's enough to pass conventional newborn (heelstick) screening, but may not be enough for normal brain development, putting baby Cora at risk for seizures and cognitive impairment. But thanks to an experimental study in which Cora's DNA was sequenced after birth, this condition was discovered and she is being treated with a safe and inexpensive vitamin supplement.

Stories like these are beginning to emerge from the BabySeq Project, the first clinical trial in the world to systematically sequence healthy newborn infants. This trial was led by my research group with funding from the National Institutes of Health. While still controversial, it is pointing the way to a future in which adults, or even newborns, can receive comprehensive genetic analysis in order to determine their risk of future disease and enable opportunities to prevent them.

Some believe that medicine is still not ready for genomic population screening, but others feel it is long overdue. After all, the sequencing of the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, and with this milestone, it became feasible to sequence and interpret the genome of any human being. The costs have come down dramatically since then; an entire human genome can now be sequenced for about $800, although the costs of bioinformatic and medical interpretation can add another $200 to $2000 more, depending upon the number of genes interrogated and the sophistication of the interpretive effort.

Two-year-old Cora Stetson, whose DNA sequencing after birth identified a potentially dangerous genetic mutation in time for her to receive preventive treatment.

(Photo courtesy of Robert Green)

The ability to sequence the human genome yielded extraordinary benefits in scientific discovery, disease diagnosis, and targeted cancer treatment. But the ability of genomes to detect health risks in advance, to actually predict the medical future of an individual, has been mired in controversy and slow to manifest. In particular, the oft-cited vision that healthy infants could be genetically tested at birth in order to predict and prevent the diseases they would encounter, has proven to be far tougher to implement than anyone anticipated.

But in the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach. Why did it take so long? And what remains to be done?

Great Expectations

Part of the problem was the unrealistic expectations that had been building for years in advance of the genomic science itself. For example, the 1997 film Gattaca portrayed a near future in which the lifetime risk of disease was readily predicted the moment an infant is born. In the fanfare that accompanied the completion of the Human Genome Project, the notion of predicting and preventing future disease in an individual became a powerful meme that was used to inspire investment and public support for genomic research long before the tools were in place to make it happen.

Another part of the problem was the success of state-mandated newborn screening programs that began in the 1960's with biochemical tests of the "heel-stick" for babies with metabolic disorders. These programs have worked beautifully, costing only a few dollars per baby and saving thousands of infants from death and severe cognitive impairment. It seemed only logical that a new technology like genome sequencing would add power and promise to such programs. But instead of embracing the notion of newborn sequencing, newborn screening laboratories have thus far rejected the entire idea as too expensive, too ambiguous, and too threatening to the comfortable constituency that they had built within the public health framework.

"What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Creating the Evidence Base for Preventive Genomics

Despite a number of obstacles, there are researchers who are exploring how to achieve the original vision of genomic testing as a tool for disease prediction and prevention. For example, in our NIH-funded MedSeq Project, we were the first to ask the question: "What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Most people do not understand that genetic information comes in four separate categories: 1) dominant mutations putting the individual at risk for rare conditions like familial forms of heart disease or cancer, (2) recessive mutations putting the individual's children at risk for rare conditions like cystic fibrosis or PKU, (3) variants across the genome that can be tallied to construct polygenic risk scores for common conditions like heart disease or type 2 diabetes, and (4) variants that can influence drug metabolism or predict drug side effects such as the muscle pain that occasionally occurs with statin use.

The technological and analytical challenges of our study were formidable, because we decided to systematically interrogate over 5000 disease-associated genes and report results in all four categories of genetic information directly to the primary care physicians for each of our volunteers. We enrolled 200 adults and found that everyone who was sequenced had medically relevant polygenic and pharmacogenomic results, over 90 percent carried recessive mutations that could have been important to reproduction, and an extraordinary 14.5 percent carried dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions.

A few years later we launched the BabySeq Project. In this study, we restricted the number of genes to include only those with child/adolescent onset that could benefit medically from early warning, and even so, we found 9.4 percent carried dominant mutations for rare conditions.

At first, our interpretation around the high proportion of apparently healthy individuals with dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions was simple – that these conditions had lower "penetrance" than anticipated; in other words, only a small proportion of those who carried the dominant mutation would get the disease. If this interpretation were to hold, then genetic risk information might be far less useful than we had hoped.

Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

But then we circled back with each adult or infant in order to examine and test them for any possible features of the rare disease in question. When we did this, we were surprised to see that in over a quarter of those carrying such mutations, there were already subtle signs of the disease in question that had not even been suspected! Now our interpretation was different. We now believe that genetic risk may be responsible for subclinical disease in a much higher proportion of people than has ever been suspected!

Meanwhile, colleagues of ours have been demonstrating that detailed analysis of polygenic risk scores can identify individuals at high risk for common conditions like heart disease. So adding up the medically relevant results in any given genome, we start to see that you can learn your risks for a rare monogenic condition, a common polygenic condition, a bad effect from a drug you might take in the future, or for having a child with a devastating recessive condition. Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

Preventive Genomics Arrives in Clinical Medicine

There is still considerable evidence to gather before we can recommend genomic screening for the entire population. For example, it is important to make sure that families who learn about such risks do not suffer harms or waste resources from excessive medical attention. And many doctors don't yet have guidance on how to use such information with their patients. But our research is convincing many people that preventive genomics is coming and that it will save lives.

In fact, we recently launched a Preventive Genomics Clinic at Brigham and Women's Hospital where information-seeking adults can obtain predictive genomic testing with the highest quality interpretation and medical context, and be coached over time in light of their disease risks toward a healthier outcome. Insurance doesn't yet cover such testing, so patients must pay out of pocket for now, but they can choose from a menu of genetic screening tests, all of which are more comprehensive than consumer-facing products. Genetic counseling is available but optional. So far, this service is for adults only, but sequencing for children will surely follow soon.

As the costs of sequencing and other Omics technologies continue to decline, we will see both responsible and irresponsible marketing of genetic testing, and we will need to guard against unscientific claims. But at the same time, we must be far more imaginative and fast moving in mainstream medicine than we have been to date in order to claim the emerging benefits of preventive genomics where it is now clear that suffering can be averted, and lives can be saved. The future has arrived if we are bold enough to grasp it.

Funding and Disclosures:

Dr. Green's research is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense and through donations to The Franca Sozzani Fund for Preventive Genomics. Dr. Green receives compensation for advising the following companies: AIA, Applied Therapeutics, Helix, Ohana, OptraHealth, Prudential, Verily and Veritas; and is co-founder and advisor to Genome Medical, Inc, a technology and services company providing genetics expertise to patients, providers, employers and care systems.

Dr. May Edward Chinn, Kizzmekia Corbett, PhD., and Alice Ball, among others, have been behind some of the most important scientific work of the last century.

If you look back on the last century of scientific achievements, you might notice that most of the scientists we celebrate are overwhelmingly white, while scientists of color take a backseat. Since the Nobel Prize was introduced in 1901, for example, no black scientists have landed this prestigious award.

The work of black women scientists has gone unrecognized in particular. Their work uncredited and often stolen, black women have nevertheless contributed to some of the most important advancements of the last 100 years, from the polio vaccine to GPS.

Here are five black women who have changed science forever.

Dr. May Edward Chinn

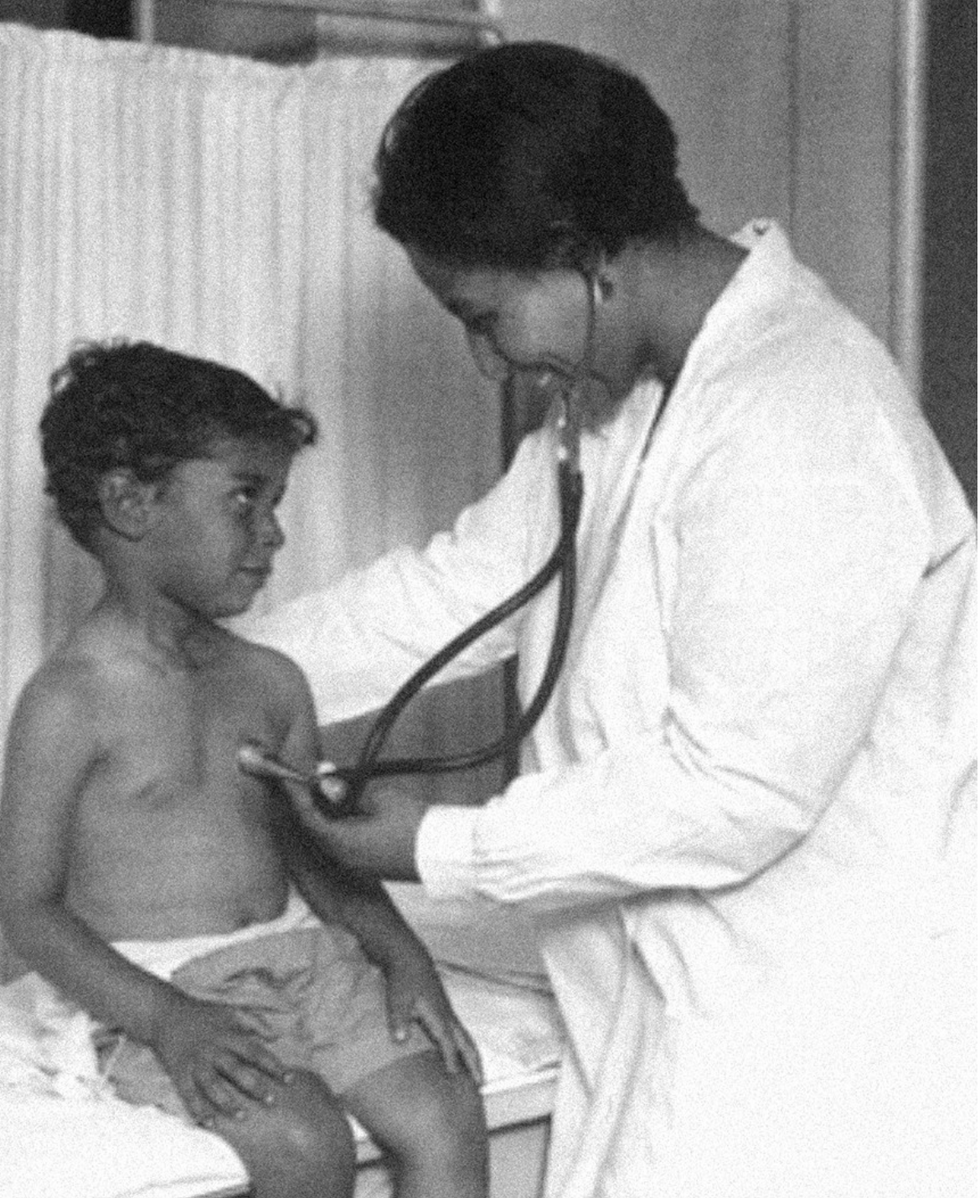

Dr. May Edward Chinn practicing medicine in Harlem

George B. Davis, PhD.

Chinn was born to poor parents in New York City just before the start of the 20th century. Although she showed great promise as a pianist, playing with the legendary musician Paul Robeson throughout the 1920s, she decided to study medicine instead. Chinn, like other black doctors of the time, were barred from studying or practicing in New York hospitals. So Chinn formed a private practice and made house calls, sometimes operating in patients’ living rooms, using an ironing board as a makeshift operating table.

Chinn worked among the city’s poor, and in doing this, started to notice her patients had late-stage cancers that often had gone undetected or untreated for years. To learn more about cancer and its prevention, Chinn begged information off white doctors who were willing to share with her, and even accompanied her patients to other clinic appointments in the city, claiming to be the family physician. Chinn took this information and integrated it into her own practice, creating guidelines for early cancer detection that were revolutionary at the time—for instance, checking patient health histories, checking family histories, performing routine pap smears, and screening patients for cancer even before they showed symptoms. For years, Chinn was the only black female doctor working in Harlem, and she continued to work closely with the poor and advocate for early cancer screenings until she retired at age 81.

Alice Ball

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Alice Ball was a chemist best known for her groundbreaking work on the development of the “Ball Method,” the first successful treatment for those suffering from leprosy during the early 20th century.

In 1916, while she was an undergraduate student at the University of Hawaii, Ball studied the effects of Chaulmoogra oil in treating leprosy. This oil was a well-established therapy in Asian countries, but it had such a foul taste and led to such unpleasant side effects that many patients refused to take it.

So Ball developed a method to isolate and extract the active compounds from Chaulmoogra oil to create an injectable medicine. This marked a significant breakthrough in leprosy treatment and became the standard of care for several decades afterward.

Unfortunately, Ball died before she could publish her results, and credit for this discovery was given to another scientist. One of her colleagues, however, was able to properly credit her in a publication in 1922.

Henrietta Lacks

onathan Newton/The Washington Post/Getty

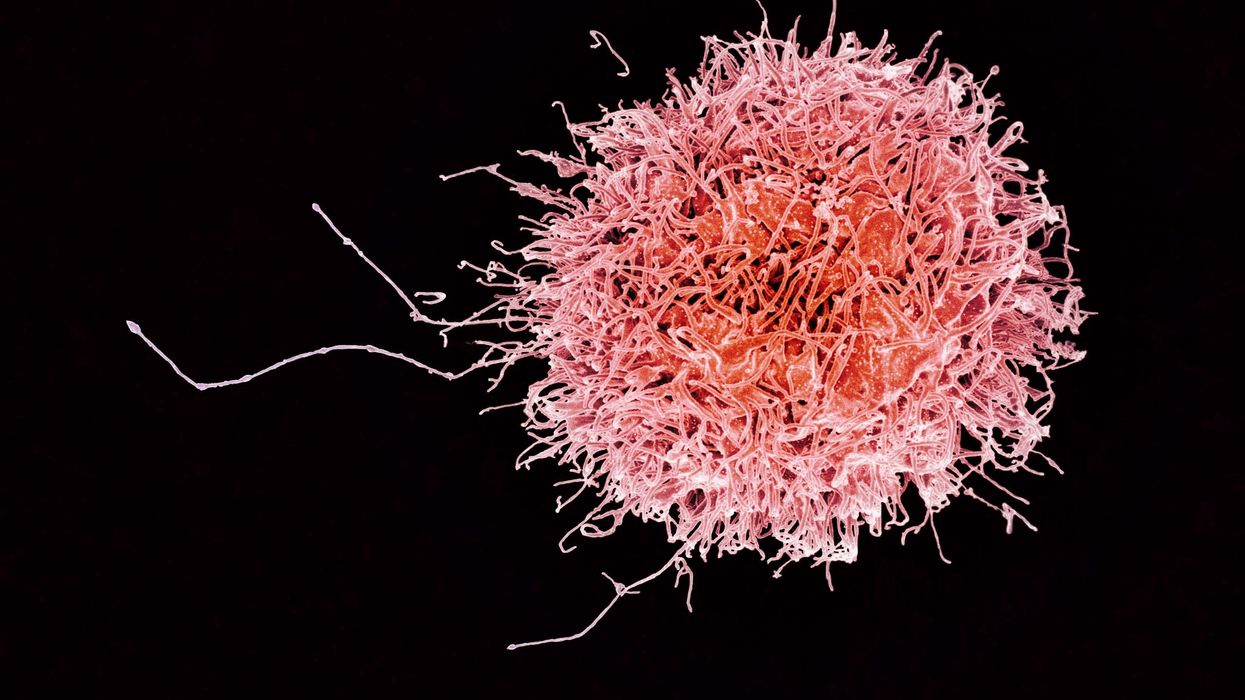

The person who arguably contributed the most to scientific research in the last century, surprisingly, wasn’t even a scientist. Henrietta Lacks was a tobacco farmer and mother of five children who lived in Maryland during the 1940s. In 1951, Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital where doctors found a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Before treating the tumor, the doctor who examined Lacks clipped two small samples of tissue from Lacks’ cervix without her knowledge or consent—something unthinkable today thanks to informed consent practices, but commonplace back then.

As Lacks underwent treatment for her cancer, her tissue samples made their way to the desk of George Otto Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins. He noticed that unlike the other cell cultures that came into his lab, Lacks’ cells grew and multiplied instead of dying out. Lacks’ cells were “immortal,” meaning that because of a genetic defect, they were able to reproduce indefinitely as long as certain conditions were kept stable inside the lab.

Gey started shipping Lacks’ cells to other researchers across the globe, and scientists were thrilled to have an unlimited amount of sturdy human cells with which to experiment. Long after Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, her cells continued to multiply and scientists continued to use them to develop cancer treatments, to learn more about HIV/AIDS, to pioneer fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization, and to develop the polio vaccine. To this day, Lacks’ cells have saved an estimated 10 million lives, and her family is beginning to get the compensation and recognition that Henrietta deserved.

Dr. Gladys West

Andre West

Gladys West was a mathematician who helped invent something nearly everyone uses today. West started her career in the 1950s at the Naval Surface Warfare Center Dahlgren Division in Virginia, and took data from satellites to create a mathematical model of the Earth’s shape and gravitational field. This important work would lay the groundwork for the technology that would later become the Global Positioning System, or GPS. West’s work was not widely recognized until she was honored by the US Air Force in 2018.

Dr. Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Corbett

TIME Magazine

At just 35 years old, immunologist Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett has already made history. A viral immunologist by training, Corbett studied coronaviruses at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and researched possible vaccines for coronaviruses such as SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome).

At the start of the COVID pandemic, Corbett and her team at the NIH partnered with pharmaceutical giant Moderna to develop an mRNA-based vaccine against the virus. Corbett’s previous work with mRNA and coronaviruses was vital in developing the vaccine, which became one of the first to be authorized for emergency use in the United States. The vaccine, along with others, is responsible for saving an estimated 14 million lives.On today’s episode of Making Sense of Science, I’m honored to be joined by Dr. Paul Song, a physician, oncologist, progressive activist and biotech chief medical officer. Through his company, NKGen Biotech, Dr. Song is leveraging the power of patients’ own immune systems by supercharging the body’s natural killer cells to make new treatments for Alzheimer’s and cancer.

Whereas other treatments for Alzheimer’s focus directly on reducing the build-up of proteins in the brain such as amyloid and tau in patients will mild cognitive impairment, NKGen is seeking to help patients that much of the rest of the medical community has written off as hopeless cases, those with late stage Alzheimer’s. And in small studies, NKGen has shown remarkable results, even improvement in the symptoms of people with these very progressed forms of Alzheimer’s, above and beyond slowing down the disease.

In the realm of cancer, Dr. Song is similarly setting his sights on another group of patients for whom treatment options are few and far between: people with solid tumors. Whereas some gradual progress has been made in treating blood cancers such as certain leukemias in past few decades, solid tumors have been even more of a challenge. But Dr. Song’s approach of using natural killer cells to treat solid tumors is promising. You may have heard of CAR-T, which uses genetic engineering to introduce cells into the body that have a particular function to help treat a disease. NKGen focuses on other means to enhance the 40 plus receptors of natural killer cells, making them more receptive and sensitive to picking out cancer cells.

Paul Y. Song, MD is currently CEO and Vice Chairman of NKGen Biotech. Dr. Song’s last clinical role was Asst. Professor at the Samuel Oschin Cancer Center at Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Dr. Song served as the very first visiting fellow on healthcare policy in the California Department of Insurance in 2013. He is currently on the advisory board of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago and a board member of Mercy Corps, The Center for Health and Democracy, and Gideon’s Promise.

Dr. Song graduated with honors from the University of Chicago and received his MD from George Washington University. He completed his residency in radiation oncology at the University of Chicago where he served as Chief Resident and did a brachytherapy fellowship at the Institute Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. He was also awarded an ASTRO research fellowship in 1995 for his research in radiation inducible gene therapy.

With Dr. Song’s leadership, NKGen Biotech’s work on natural killer cells represents cutting-edge science leading to key findings and important pieces of the puzzle for treating two of humanity’s most intractable diseases.

Show links

- Paul Song LinkedIn

- NKGen Biotech on Twitter - @NKGenBiotech

- NKGen Website: https://nkgenbiotech.com/

- NKGen appoints Paul Song

- Patient Story: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/long-island/promising-new-treatment-for-advanced-alzheimers-patients/

- FDA Clearance: https://nkgenbiotech.com/nkgen-biotech-receives-ind-clearance-from-fda-for-snk02-allogeneic-natural-killer-cell-therapy-for-solid-tumors/Q3 earnings data: https://www.nasdaq.com/press-release/nkgen-biotech-inc.-reports-third-quarter-2023-financial-results-and-business