Genetically Sequencing Healthy Babies Yielded Surprising Results

A newborn and mother in the hospital - first touch. (© martin81/Shutterstock)

Today in Melrose, Massachusetts, Cora Stetson is the picture of good health, a bubbly precocious 2-year-old. But Cora has two separate mutations in the gene that produces a critical enzyme called biotinidase and her body produces only 40 percent of the normal levels of that enzyme.

In the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach.

That's enough to pass conventional newborn (heelstick) screening, but may not be enough for normal brain development, putting baby Cora at risk for seizures and cognitive impairment. But thanks to an experimental study in which Cora's DNA was sequenced after birth, this condition was discovered and she is being treated with a safe and inexpensive vitamin supplement.

Stories like these are beginning to emerge from the BabySeq Project, the first clinical trial in the world to systematically sequence healthy newborn infants. This trial was led by my research group with funding from the National Institutes of Health. While still controversial, it is pointing the way to a future in which adults, or even newborns, can receive comprehensive genetic analysis in order to determine their risk of future disease and enable opportunities to prevent them.

Some believe that medicine is still not ready for genomic population screening, but others feel it is long overdue. After all, the sequencing of the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, and with this milestone, it became feasible to sequence and interpret the genome of any human being. The costs have come down dramatically since then; an entire human genome can now be sequenced for about $800, although the costs of bioinformatic and medical interpretation can add another $200 to $2000 more, depending upon the number of genes interrogated and the sophistication of the interpretive effort.

Two-year-old Cora Stetson, whose DNA sequencing after birth identified a potentially dangerous genetic mutation in time for her to receive preventive treatment.

(Photo courtesy of Robert Green)

The ability to sequence the human genome yielded extraordinary benefits in scientific discovery, disease diagnosis, and targeted cancer treatment. But the ability of genomes to detect health risks in advance, to actually predict the medical future of an individual, has been mired in controversy and slow to manifest. In particular, the oft-cited vision that healthy infants could be genetically tested at birth in order to predict and prevent the diseases they would encounter, has proven to be far tougher to implement than anyone anticipated.

But in the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach. Why did it take so long? And what remains to be done?

Great Expectations

Part of the problem was the unrealistic expectations that had been building for years in advance of the genomic science itself. For example, the 1997 film Gattaca portrayed a near future in which the lifetime risk of disease was readily predicted the moment an infant is born. In the fanfare that accompanied the completion of the Human Genome Project, the notion of predicting and preventing future disease in an individual became a powerful meme that was used to inspire investment and public support for genomic research long before the tools were in place to make it happen.

Another part of the problem was the success of state-mandated newborn screening programs that began in the 1960's with biochemical tests of the "heel-stick" for babies with metabolic disorders. These programs have worked beautifully, costing only a few dollars per baby and saving thousands of infants from death and severe cognitive impairment. It seemed only logical that a new technology like genome sequencing would add power and promise to such programs. But instead of embracing the notion of newborn sequencing, newborn screening laboratories have thus far rejected the entire idea as too expensive, too ambiguous, and too threatening to the comfortable constituency that they had built within the public health framework.

"What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Creating the Evidence Base for Preventive Genomics

Despite a number of obstacles, there are researchers who are exploring how to achieve the original vision of genomic testing as a tool for disease prediction and prevention. For example, in our NIH-funded MedSeq Project, we were the first to ask the question: "What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Most people do not understand that genetic information comes in four separate categories: 1) dominant mutations putting the individual at risk for rare conditions like familial forms of heart disease or cancer, (2) recessive mutations putting the individual's children at risk for rare conditions like cystic fibrosis or PKU, (3) variants across the genome that can be tallied to construct polygenic risk scores for common conditions like heart disease or type 2 diabetes, and (4) variants that can influence drug metabolism or predict drug side effects such as the muscle pain that occasionally occurs with statin use.

The technological and analytical challenges of our study were formidable, because we decided to systematically interrogate over 5000 disease-associated genes and report results in all four categories of genetic information directly to the primary care physicians for each of our volunteers. We enrolled 200 adults and found that everyone who was sequenced had medically relevant polygenic and pharmacogenomic results, over 90 percent carried recessive mutations that could have been important to reproduction, and an extraordinary 14.5 percent carried dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions.

A few years later we launched the BabySeq Project. In this study, we restricted the number of genes to include only those with child/adolescent onset that could benefit medically from early warning, and even so, we found 9.4 percent carried dominant mutations for rare conditions.

At first, our interpretation around the high proportion of apparently healthy individuals with dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions was simple – that these conditions had lower "penetrance" than anticipated; in other words, only a small proportion of those who carried the dominant mutation would get the disease. If this interpretation were to hold, then genetic risk information might be far less useful than we had hoped.

Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

But then we circled back with each adult or infant in order to examine and test them for any possible features of the rare disease in question. When we did this, we were surprised to see that in over a quarter of those carrying such mutations, there were already subtle signs of the disease in question that had not even been suspected! Now our interpretation was different. We now believe that genetic risk may be responsible for subclinical disease in a much higher proportion of people than has ever been suspected!

Meanwhile, colleagues of ours have been demonstrating that detailed analysis of polygenic risk scores can identify individuals at high risk for common conditions like heart disease. So adding up the medically relevant results in any given genome, we start to see that you can learn your risks for a rare monogenic condition, a common polygenic condition, a bad effect from a drug you might take in the future, or for having a child with a devastating recessive condition. Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

Preventive Genomics Arrives in Clinical Medicine

There is still considerable evidence to gather before we can recommend genomic screening for the entire population. For example, it is important to make sure that families who learn about such risks do not suffer harms or waste resources from excessive medical attention. And many doctors don't yet have guidance on how to use such information with their patients. But our research is convincing many people that preventive genomics is coming and that it will save lives.

In fact, we recently launched a Preventive Genomics Clinic at Brigham and Women's Hospital where information-seeking adults can obtain predictive genomic testing with the highest quality interpretation and medical context, and be coached over time in light of their disease risks toward a healthier outcome. Insurance doesn't yet cover such testing, so patients must pay out of pocket for now, but they can choose from a menu of genetic screening tests, all of which are more comprehensive than consumer-facing products. Genetic counseling is available but optional. So far, this service is for adults only, but sequencing for children will surely follow soon.

As the costs of sequencing and other Omics technologies continue to decline, we will see both responsible and irresponsible marketing of genetic testing, and we will need to guard against unscientific claims. But at the same time, we must be far more imaginative and fast moving in mainstream medicine than we have been to date in order to claim the emerging benefits of preventive genomics where it is now clear that suffering can be averted, and lives can be saved. The future has arrived if we are bold enough to grasp it.

Funding and Disclosures:

Dr. Green's research is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense and through donations to The Franca Sozzani Fund for Preventive Genomics. Dr. Green receives compensation for advising the following companies: AIA, Applied Therapeutics, Helix, Ohana, OptraHealth, Prudential, Verily and Veritas; and is co-founder and advisor to Genome Medical, Inc, a technology and services company providing genetics expertise to patients, providers, employers and care systems.

The Next 100 Years of Scientific Progress Could Look Like This

From nanobots that kill cancer to carbon-neutral biofuels, we envisioned what the next century could bring.

In just 100 years, scientific breakthroughs could completely transform humanity and our planet for the better. Here's a glimpse at what our future may hold.

The Next 100 Years of Scientific Progress

Kira Peikoff was the editor-in-chief of Leaps.org from 2017 to 2021. As a journalist, her work has appeared in The New York Times, Newsweek, Nautilus, Popular Mechanics, The New York Academy of Sciences, and other outlets. She is also the author of four suspense novels that explore controversial issues arising from scientific innovation: Living Proof, No Time to Die, Die Again Tomorrow, and Mother Knows Best. Peikoff holds a B.A. in Journalism from New York University and an M.S. in Bioethics from Columbia University. She lives in New Jersey with her husband and two young sons. Follow her on Twitter @KiraPeikoff.

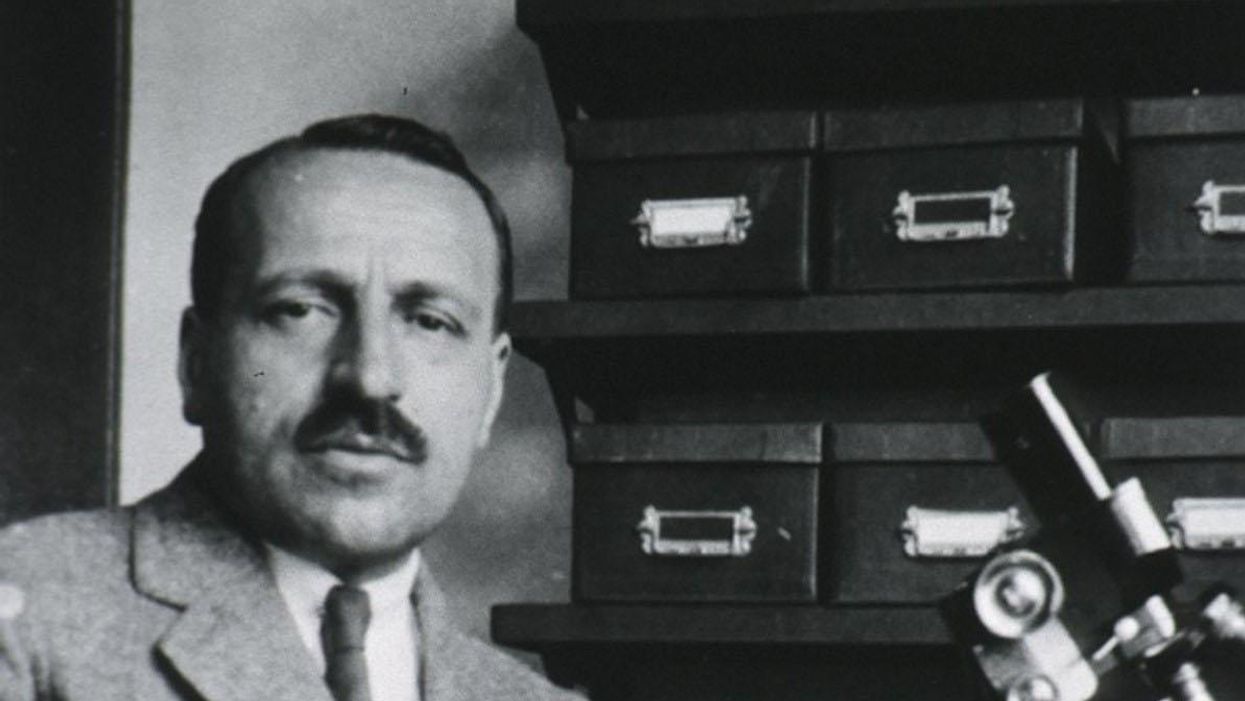

George Papanicolaou (1883-1962), Greek-born American physician developed a simple cytological test for cervical cancer in 1928.

For decades, women around the world have made the annual pilgrimage to their doctor for the dreaded but potentially life-saving Papanicolaou test, a gynecological exam to screen for cervical cancer named for Georgios Papanicolaou, the Greek immigrant who developed it.

The Pap smear, as it is commonly known, is credited for reducing cervical cancer mortality by 70% since the 1960s; the American Cancer Society (ACS) still ranks the Pap as the most successful screening test for preventing serious malignancies. Nonetheless, the agency, as well as other medical panels, including the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology are making a strong push to replace the Pap with the more sensitive high-risk HPV screening test for the human papillomavirus virus, which causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

So, how was the Pap developed and how did it become the gold standard of cervical cancer detection for more than 60 years?

Born on May 13, 1883, on the island of Euboea, Greece, Georgios Papanicolaou attended the University of Athens where he majored in music and the humanities before earning his medical degree in 1904 and PhD from the University of Munich six years later. In Europe, Papanicolaou was an assistant military surgeon during the Balkan War, a psychologist for an expedition of the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco and a caregiver for leprosy patients.

When he and his wife, Andromache Mavroyenous (Mary), arrived at Ellis Island on October 19, 1913, the young couple had scarcely more than the $250 minimum required to immigrate, spoke no English and had no job prospects. They worked a series of menial jobs--department store sales clerk, rug salesman, newspaper clerk, restaurant violinist--before Papanicolaou landed a position as an anatomy assistant at Cornell University and Mary was hired as his lab assistant, an arrangement that would last for the next 50 years.

Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

In his early research, Papanikolaou used guinea pigs to prove that gender is determined by the X and Y chromosomes. Using a pediatric nasal speculum, he collected and microscopically examined vaginal secretions of guinea pigs, which revealed distinct cell changes connected to the menstrual cycle. He moved on to study reproductive patterns in humans, beginning with his faithful wife, Mary, who not only endured his almost-daily cervical exams for decades, but also recruited friends as early research participants.

Writing in the medical journal Growth in 1920, the scientist outlined his theory that a microscopic smear of vaginal fluid could detect the presence of cancer cells in the uterus. Papanikolaou would later say the discovery "was one of the greatest thrills I ever experienced during my scientific career."

At this time, cervical cancer was the number one cancer killer of American women but physicians were skeptical of these new findings. They continued to rely on biopsy and curettage to diagnose and treat the disease until Papanicolaou's discovery was published in American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. An inexpensive, easy-to-perform test that could detect cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases was a sea change. Between 1975 and 2001, the cervical cancer rate was cut in half.

Papanicolaou became Emeritus Professor at Cornell University Medical College and received numerous awards, including the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society. His image was featured on the Greek currency and the US Post Office issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. But international acclaim didn't lead to a more relaxed schedule. The researcher continued to work seven days a week and refused to take vacations.

After nearly 50 years, Papanicolaou left Cornell to head and develop the Cancer Institute of Miami. He died of a heart attack on February 19, 1962, just three months after his arrival. Mary continued to work in the renamed Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute until her death 20 years later.

The annual pap smear was originally tied to renewing a birth control prescription. Canada began recommending Pap exams every three years in 1978. The United States followed suit in 2012, noting that it takes many years for cervical cancer to develop. In September 2020, the American Cancer Society recommended delaying the first gynecological pelvic exam until age 25 and replacing the Pap test completely with the more accurate human papillomavirus (HPV) test every five years as the technology becomes more widely available.

Not everyone agrees that it's time to do away with this proven screening method, though. The incidence rate of cervical cancer among Hispanic women is 28% higher than for white women, and Black women are more likely to die of cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnicities.

Whether the Pap is administered every year, every three years or not at all, Papanicolaou will always be known as the medical hero who saved countless women who would otherwise have succumbed to cervical cancer.