Genetically Sequencing Healthy Babies Yielded Surprising Results

A newborn and mother in the hospital - first touch. (© martin81/Shutterstock)

Today in Melrose, Massachusetts, Cora Stetson is the picture of good health, a bubbly precocious 2-year-old. But Cora has two separate mutations in the gene that produces a critical enzyme called biotinidase and her body produces only 40 percent of the normal levels of that enzyme.

In the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach.

That's enough to pass conventional newborn (heelstick) screening, but may not be enough for normal brain development, putting baby Cora at risk for seizures and cognitive impairment. But thanks to an experimental study in which Cora's DNA was sequenced after birth, this condition was discovered and she is being treated with a safe and inexpensive vitamin supplement.

Stories like these are beginning to emerge from the BabySeq Project, the first clinical trial in the world to systematically sequence healthy newborn infants. This trial was led by my research group with funding from the National Institutes of Health. While still controversial, it is pointing the way to a future in which adults, or even newborns, can receive comprehensive genetic analysis in order to determine their risk of future disease and enable opportunities to prevent them.

Some believe that medicine is still not ready for genomic population screening, but others feel it is long overdue. After all, the sequencing of the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003, and with this milestone, it became feasible to sequence and interpret the genome of any human being. The costs have come down dramatically since then; an entire human genome can now be sequenced for about $800, although the costs of bioinformatic and medical interpretation can add another $200 to $2000 more, depending upon the number of genes interrogated and the sophistication of the interpretive effort.

Two-year-old Cora Stetson, whose DNA sequencing after birth identified a potentially dangerous genetic mutation in time for her to receive preventive treatment.

(Photo courtesy of Robert Green)

The ability to sequence the human genome yielded extraordinary benefits in scientific discovery, disease diagnosis, and targeted cancer treatment. But the ability of genomes to detect health risks in advance, to actually predict the medical future of an individual, has been mired in controversy and slow to manifest. In particular, the oft-cited vision that healthy infants could be genetically tested at birth in order to predict and prevent the diseases they would encounter, has proven to be far tougher to implement than anyone anticipated.

But in the last few years, the dream of predicting and preventing diseases through genomics, starting in childhood, is finally within reach. Why did it take so long? And what remains to be done?

Great Expectations

Part of the problem was the unrealistic expectations that had been building for years in advance of the genomic science itself. For example, the 1997 film Gattaca portrayed a near future in which the lifetime risk of disease was readily predicted the moment an infant is born. In the fanfare that accompanied the completion of the Human Genome Project, the notion of predicting and preventing future disease in an individual became a powerful meme that was used to inspire investment and public support for genomic research long before the tools were in place to make it happen.

Another part of the problem was the success of state-mandated newborn screening programs that began in the 1960's with biochemical tests of the "heel-stick" for babies with metabolic disorders. These programs have worked beautifully, costing only a few dollars per baby and saving thousands of infants from death and severe cognitive impairment. It seemed only logical that a new technology like genome sequencing would add power and promise to such programs. But instead of embracing the notion of newborn sequencing, newborn screening laboratories have thus far rejected the entire idea as too expensive, too ambiguous, and too threatening to the comfortable constituency that they had built within the public health framework.

"What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Creating the Evidence Base for Preventive Genomics

Despite a number of obstacles, there are researchers who are exploring how to achieve the original vision of genomic testing as a tool for disease prediction and prevention. For example, in our NIH-funded MedSeq Project, we were the first to ask the question: "What can you find when you look as deeply as possible into the medical genomes of healthy individuals?"

Most people do not understand that genetic information comes in four separate categories: 1) dominant mutations putting the individual at risk for rare conditions like familial forms of heart disease or cancer, (2) recessive mutations putting the individual's children at risk for rare conditions like cystic fibrosis or PKU, (3) variants across the genome that can be tallied to construct polygenic risk scores for common conditions like heart disease or type 2 diabetes, and (4) variants that can influence drug metabolism or predict drug side effects such as the muscle pain that occasionally occurs with statin use.

The technological and analytical challenges of our study were formidable, because we decided to systematically interrogate over 5000 disease-associated genes and report results in all four categories of genetic information directly to the primary care physicians for each of our volunteers. We enrolled 200 adults and found that everyone who was sequenced had medically relevant polygenic and pharmacogenomic results, over 90 percent carried recessive mutations that could have been important to reproduction, and an extraordinary 14.5 percent carried dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions.

A few years later we launched the BabySeq Project. In this study, we restricted the number of genes to include only those with child/adolescent onset that could benefit medically from early warning, and even so, we found 9.4 percent carried dominant mutations for rare conditions.

At first, our interpretation around the high proportion of apparently healthy individuals with dominant mutations for rare genetic conditions was simple – that these conditions had lower "penetrance" than anticipated; in other words, only a small proportion of those who carried the dominant mutation would get the disease. If this interpretation were to hold, then genetic risk information might be far less useful than we had hoped.

Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

But then we circled back with each adult or infant in order to examine and test them for any possible features of the rare disease in question. When we did this, we were surprised to see that in over a quarter of those carrying such mutations, there were already subtle signs of the disease in question that had not even been suspected! Now our interpretation was different. We now believe that genetic risk may be responsible for subclinical disease in a much higher proportion of people than has ever been suspected!

Meanwhile, colleagues of ours have been demonstrating that detailed analysis of polygenic risk scores can identify individuals at high risk for common conditions like heart disease. So adding up the medically relevant results in any given genome, we start to see that you can learn your risks for a rare monogenic condition, a common polygenic condition, a bad effect from a drug you might take in the future, or for having a child with a devastating recessive condition. Suddenly the information available in the genome of even an apparently healthy individual is looking more robust, and the prospect of preventive genomics is looking feasible.

Preventive Genomics Arrives in Clinical Medicine

There is still considerable evidence to gather before we can recommend genomic screening for the entire population. For example, it is important to make sure that families who learn about such risks do not suffer harms or waste resources from excessive medical attention. And many doctors don't yet have guidance on how to use such information with their patients. But our research is convincing many people that preventive genomics is coming and that it will save lives.

In fact, we recently launched a Preventive Genomics Clinic at Brigham and Women's Hospital where information-seeking adults can obtain predictive genomic testing with the highest quality interpretation and medical context, and be coached over time in light of their disease risks toward a healthier outcome. Insurance doesn't yet cover such testing, so patients must pay out of pocket for now, but they can choose from a menu of genetic screening tests, all of which are more comprehensive than consumer-facing products. Genetic counseling is available but optional. So far, this service is for adults only, but sequencing for children will surely follow soon.

As the costs of sequencing and other Omics technologies continue to decline, we will see both responsible and irresponsible marketing of genetic testing, and we will need to guard against unscientific claims. But at the same time, we must be far more imaginative and fast moving in mainstream medicine than we have been to date in order to claim the emerging benefits of preventive genomics where it is now clear that suffering can be averted, and lives can be saved. The future has arrived if we are bold enough to grasp it.

Funding and Disclosures:

Dr. Green's research is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Defense and through donations to The Franca Sozzani Fund for Preventive Genomics. Dr. Green receives compensation for advising the following companies: AIA, Applied Therapeutics, Helix, Ohana, OptraHealth, Prudential, Verily and Veritas; and is co-founder and advisor to Genome Medical, Inc, a technology and services company providing genetics expertise to patients, providers, employers and care systems.

How Smallpox Was Wiped Off the Planet By a Vaccine and Global Cooperation

The world's last recorded case of endemic smallpox was in Ali Maow Maalin, of Merka, Somalia, in October 1977. He made a full recovery.

For 3000 years, civilizations all over the world were brutalized by smallpox, an infectious and deadly virus characterized by fever and a rash of painful, oozing sores.

Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success.

Smallpox was merciless, killing one third of people it infected and leaving many survivors permanently pockmarked and blind. Although smallpox was more common during the 18th and 19th centuries, it was still a leading cause of death even up until the early 1950s, killing an estimated 50 million people annually.

A Primitive Cure

Sometime during the 10th century, Chinese physicians figured out that exposing people to a tiny bit of smallpox would sometimes result in a milder infection and immunity to the disease afterward (if the person survived). Desperate for a cure, people would huff powders made of smallpox scabs or insert smallpox pus into their skin, all in the hopes of getting immunity without having to get too sick. However, this method – called inoculation – didn't always work. People could still catch the full-blown disease, spread it to others, or even catch another infectious disease like syphilis in the process.

A Breakthrough Treatment

For centuries, inoculation – however imperfect – was the only protection the world had against smallpox. But in the late 18th century, an English physician named Edward Jenner created a more effective method. Jenner discovered that inoculating a person with cowpox – a much milder relative of the smallpox virus – would make that person immune to smallpox as well, but this time without the possibility of actually catching or transmitting smallpox. His breakthrough became the world's first vaccine against a contagious disease. Other researchers, like Louis Pasteur, would use these same principles to make vaccines for global killers like anthrax and rabies. Vaccination was considered a miracle, conferring all of the rewards of having gotten sick (immunity) without the risk of death or blindness.

Scaling the Cure

As vaccination became more widespread, the number of global smallpox deaths began to drop, particularly in Europe and the United States. But even as late as 1967, smallpox was still killing anywhere from 10 to 15 million people in poorer parts of the globe. The World Health Assembly (a decision-making body of the World Health Organization) decided that year to launch the first coordinated effort to eradicate smallpox from the planet completely, aiming for 80 percent vaccine coverage in every country in which the disease was endemic – a total of 33 countries.

But officials knew that eradicating smallpox would be easier said than done. Doctors had to contend with wars, floods, and language barriers to make their campaign a success. The vaccination initiative in Bangladesh proved the most challenging, due to its population density and the prevalence of the disease, writes journalist Laurie Garrett in her book, The Coming Plague.

In one instance, French physician Daniel Tarantola on assignment in Bangladesh confronted a murderous gang that was thought to be spreading smallpox throughout the countryside during their crime sprees. Without police protection, Tarantola confronted the gang and "faced down guns" in order to immunize them, protecting the villagers from repeated outbreaks.

Because not enough vaccines existed to vaccinate everyone in a given country, doctors utilized a strategy called "ring vaccination," which meant locating individual outbreaks and vaccinating all known and possible contacts to stop an outbreak at its source. Fewer than 50 percent of the population in Nigeria received a vaccine, for example, but thanks to ring vaccination, it was eradicated in that country nonetheless. Doctors worked tirelessly for the next eleven years to immunize as many people as possible.

The World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

A Resounding Success

In November 1975, officials discovered a case of variola major — the more virulent strain of the smallpox virus — in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl named Rahima Banu. Banu was forcibly quarantined in her family's home with armed guards until the risk of transmission had passed, while officials went door-to-door vaccinating everyone within a five-mile radius. Two years later, the last case of variola major in human history was reported in Somalia. When no new community-acquired cases appeared after that, the World Health Organization declared smallpox officially eradicated on May 8, 1980.

Because of smallpox, we now know it's possible to completely eliminate a disease. But is it likely to happen again with other diseases, like COVID-19? Some scientists aren't so sure. As dangerous as smallpox was, it had a few characteristics that made eradication possibly easier than for other diseases. Smallpox, for instance, has no animal reservoir, meaning that it could not circulate in animals and resurge in a human population at a later date. Additionally, a person who had smallpox once was guaranteed immunity from the disease thereafter — which is not the case for COVID-19.

In The Coming Plague, Japanese physician Isao Arita, who led the WHO's Smallpox Eradication Unit, admitted to routinely defying orders from the WHO, mobilizing to parts of the world without official approval and sometimes even vaccinating people against their will. "If we hadn't broken every single WHO rule many times over, we would have never defeated smallpox," Arita said. "Never."

Still, thanks to the life-saving technology of vaccines – and the tireless efforts of doctors and scientists across the globe – a once-lethal disease is now a thing of the past.

Over 1 Million Seeds Are Buried Near the North Pole to Back Up the World’s Crops

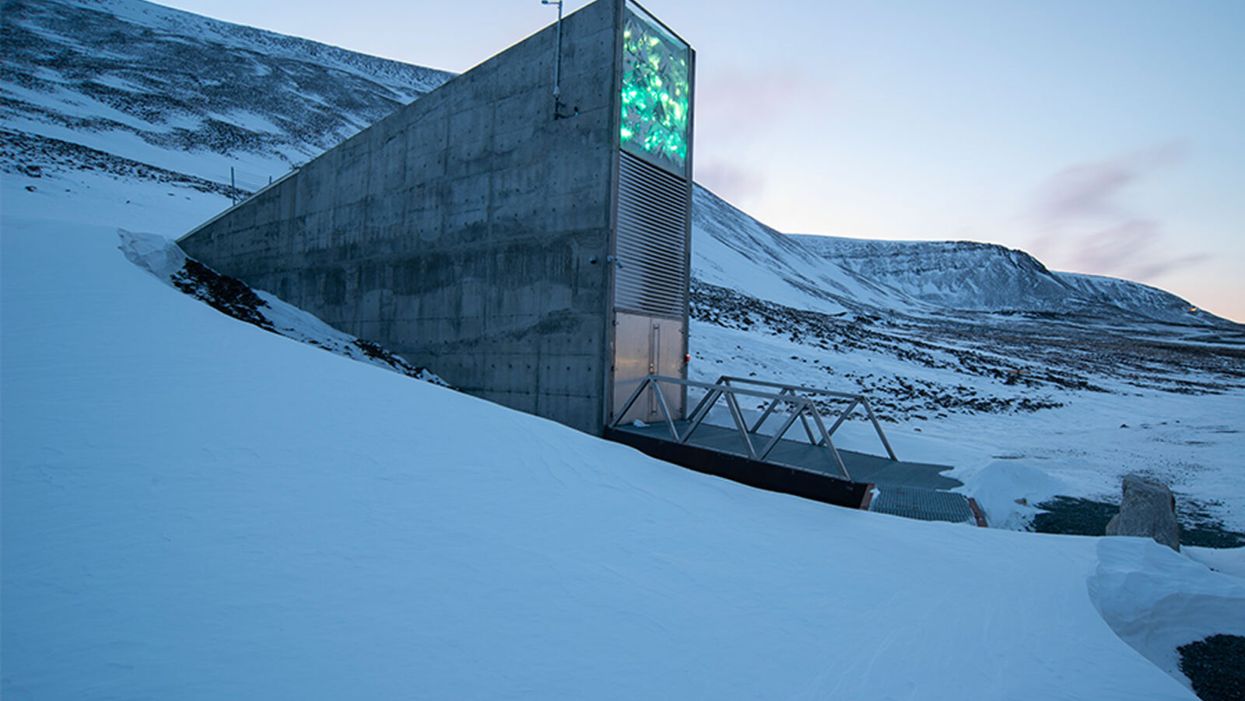

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault preserves more than one million of the world's seeds deep inside Platäfjellet Mountain.

The impressive structure protrudes from the side of a snowy mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago, a cluster of islands about halfway between Norway and the North Pole.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost. We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

Art installations on the building's rooftop and front façade glimmer like diamonds in the polar night, but it is what lies buried deep inside the frozen rock, 475 feet from the building's entrance, that is most precious. Here, in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, are backup copies of more than a million of the world's agricultural seeds.

Inside the vault, seed boxes from many gene banks and many countries. "The seeds don't know national boundaries," says Kent Nnadozie, the UN's Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

(Photo credit: Svalbard Global Seed Vault/Riccardo Gangale)

The Svalbard vault -- which has been called the Doomsday Vault, or a Noah's Ark for seeds -- preserves the genetic materials of more than 6000 crop species and their wild relatives, including many of the varieties within those species. Svalbard's collection represents all the traits that will enable the plants that feed the world to adapt – with the help of farmers and plant breeders – to rapidly changing climactic conditions, including rising temperatures, more intense drought, and increasing soil salinity. "We save these seeds because we want to ensure food security for future generations," says Grethe Helene Evjen, Senior Advisor at the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food .

A recent study in the journal Nature predicted that global warming could cause catastrophic losses of biodiversity in regions across the globe throughout this century. Yet global warming also threatens the permafrost that surrounds the seed vault, the very thing that was once considered a failsafe means of keeping these seeds frozen and safeguarding the diversity of our crops. In fact, record temperatures in Svalbard a few years ago – and a significant breach of water into the access tunnel to the vault -- prompted the Norwegian government to invest $20 million euros on improvements at the facility to further secure the genetic resources locked inside. The hope: that technology can work in concert with nature's freezer to keep the world's seeds viable.

"Before, we trusted the permafrost," says Hege Njaa Aschim, a spokesperson for Statsbygg, the government agency that recently completed the upgrades at the seed vault. "We do not trust the permafrost anymore."

The Apex of the Global Conservation System

More than 1700 genebanks around the globe preserve the diverse seed varieties from their regions. They range from small community seed banks in developing countries, where small farmers save and trade their seeds with growers in nearby villages, to specialized university collections, to national and international genetic resource repositories. But many of these facilities are vulnerable to war, natural disasters, or even lack of funding.

"If anything should happen to the resources in a regular genebank, Svalbard is the backup – it's essentially the apex of the global conservation system," says Kent Nnadozie, Secretary of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture at the United Nations, who likens the Global Vault to the Central Reserve Bank. "You have regular banks that do active trading, but the Central Bank is the final reserve where the banks store their gold deposits."

Similarly, farmers deposit their seeds in regional genebanks, and also look to these banks for new varieties to help their crops adapt to, say, increasing temperatures, or resist intrusive pests. Regional banks, in turn, store duplicates from their collections at Svalbard. These seeds remain the sovereign property of the country or institution depositing them; only they can "make a withdrawal."

The Global Vault has already proven invaluable: The International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), formerly located outside of Aleppo, Syria, held more than 140,000 seed samples, including plants that were extinct in their natural habitats, before the Syrian Crisis in 2012. Fortunately, they had managed to back up most of their seed samples at Svalbard before they were forced to relocate to Lebanon and Morocco. In 2017, ICARDA became the first – and only – organization to withdraw their stored seeds. They have now regenerated almost all of the samples at their new locations and recently redeposited new seeds for safekeeping at Svalbard.

Rapid Global Warming Threatens Permafrost

The Global Vault, a joint venture between the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Centre (NordGen) that started operating in 2008, was sited in Svalbard in part because of its remote yet accessible location: Svalbard is the northernmost inhabited spot on Earth with an airport. But experts also thought it a failsafe choice for long-term seed storage because its permafrost would offer natural freezing – even if cooling systems were to fail. No one imagined that the permafrost could fail.

"We've had record temperatures in the region recently, and there are a lot of signs that global warming is happening faster at the extreme latitudes," says Geoff Hawtin, a world-renowned authority in plant conservation, who is the founding director of -- and now advisor to -- the Crop Trust. "Svalbard is still arguably one of the safest places for the seeds from a temperature point of view, but it's actually not going to be as cold as we thought 20 years ago."

A recent report by the Norwegian Centre for Climate Services predicted that Svalbard could become 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer by the year 2100. And data from the Norwegian government's environmental monitoring system in Svalbard shows that the permafrost is already thawing: The "active layer," that is, the layer of surface soil that seasonally thaws, has become 25-30 cm thicker since 1998.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization.

Though the permafrost surrounding the seed vault chambers, which are situated well below the active layer, is still intact, the permafrost around the access tunnel never re-established as expected after construction of the Global Vault twelve years ago. As a result, when Svalbard saw record high temperatures and unprecedented rainfall in 2016, about 164 feet of rainwater and snowmelt leaked into the tunnel, turning it into a skating rink and spurring authorities to take what they called a "better safe than sorry approach." They invested in major upgrades to the facility. "The seeds in the vault were never threatened," says Aschim, "but technology has become more important at Svalbard."

Technology Gives Nature a Boost

For now, the permafrost deep inside the mountain still keeps the temperature in the vault down to about -25°F. The cooling systems then give nature a mechanical boost to keep the seed vault chilled even further, to about -64°F, the optimal temperature for conserving seeds. In addition to upgrading to a more effective and sustainable cooling system that runs on CO2, the Norwegian government added backup generators, removed heat-generating electrical equipment from inside the facility to an outside building, installed a thick, watertight door to the vault, and replaced the corrugated steel access tunnel with a cement tunnel that uses the same waterproofing technology as the North Sea oil platforms.

To re-establish the permafrost around the tunnel, they layered cooling pipes with frozen soil around the concrete tunnel, covered the frozen soil with a cooling mat, and topped the cooling mat with the original permafrost soil. They also added drainage ditches on the mountainside to divert meltwater away from the tunnel as the climate gets warmer and wetter.

New Deposits to the Global Vault

The day before COVID-19 arrived in Norway, on February 25th, Prime Minister Erna Solberg hosted the biggest seed-depositing event in the vault's history in honor of the new and improved vault. As snow fell on Svalbard, depositors from almost every continent traveled the windy road from Longyearbyen up Platåfjellet Mountain and braved frigid -8°F weather to celebrate the massive technical upgrades to the facility – and to hand over their seeds.

Among the 35 depositors were several bringing their seeds to Svalbard for the first time, including the Cherokee Nation, which deposited nine heirloom seed varieties that predate European colonization, and Israel's University of Haifa, whose deposit included multiple genotypes of wild emmer wheat, an ancient relative of the modern domesticated crop. The storage boxes carried ceremoniously over the threshold that day contained more than 65,000 new seed samples, bringing the total to more than a million, and almost filling the first of three seed chambers in the vault. (The Global Vault can store up to 4.5 million seed samples.)

"Svalbard's samples contain all the possibilities, all the options for the future of our agricultural crops – it's how crops are going to adapt," says Cary Fowler, former executive director of the Crop Trust, who was instrumental in establishing the Global Vault. "If our crops don't adapt to climate change, then neither will we." Dr. Fowler says he is confident that with the recent improvements in the vault, the seeds are going to remain viable for a very long time.

"It's sometimes tempting to get distracted by the romanticism of a seed vault inside a mountain near the North Pole – it's a little bit James Bondish," muses Dr. Fowler. "But the reality is we've essentially put an end to the extinction of more than a million samples of biodiversity forever."